Loneliness is a growing health crisis, and gender norms make men more vulnerable to digitized isolation. An ever-more frictionless online experience erodes young people’s capacity to tolerate frustration and establish lasting ties.

Finnish politics today is dominated by women, many under the age of 35. This is a result of long-standing efforts to include more women in leadership. But the failure of the previous rightwing government has also helped pave their way, as have the internal fractures in the social democratic and centre parties. Now they must clear up the mess they have inherited.

Finland’s new government entered the history books last December by appointing the world’s youngest serving prime minister, thirty-four-year-old Social Democrat Sanna Marin. That Finland’s third female prime minister, former minister of transport, steps up her duties is not much of a surprise for those who have followed her long and already substantial political career. She has been one of the top contenders to take over the leadership of the Social Democratic Party (SDP) for some time.

More interesting, however, is that Finland now has a broad centre-left ruling coalition consisting of five political parties – all led by women, four of whom are in their thirties. This is a stark contrast to the former right-wing government, dissolved last spring, in which all party leaders were middle-aged men.

The government reshuffle is a confusing affair with little practical or even political significance. It comes on the heels of a postal workers’ strike in November, which threatened to shut down Christmas commerce. The Finnish state holds the stock majority in the country’s postal service provider Posti, and the government received widespread criticism from unions and the general public as it seemed to condone slashing seven hundred package handlers’ salaries. The cuts were eventually nullified when the government stepped in, but an odd, media-fuelled brouhaha sprung up around SDP Prime Minister Antti Rinne over exactly when he had been aware of the details, and whether he had – intentionally or not – withheld this information from the rest of the government.

In a surprise move, the SDP’s government ally, the Centre Party, declared that it no longer supported Antti Rinne and demanded his resignation. The party’s official motivations for the coup were vague, and the whole thing has widely been viewed as an attempt by the Centre Party to boost their image and remove the union-backed Rinne from power.

The ‘new’ government is essentially the same five-party coalition that ruled under Rinne, only with a new PM and some minor reshuffle of ministerial portfolios. The one major consequence of this fabricated government crisis is that the Social Democrats now hold a major grudge against the Centre Party who, paradoxically, may have shot itself in the foot, as SDP’s de facto leadership change may lead to increased support for the battered Social Democrats.

Rinne will, officially, remain SDP leader until next spring’s party congress, but he has effectively been stripped of power and has stated that he will not be available for reappointment. Sanna Marin is now the leader of SDP in all but name, joined by four female party leaders in the Left Alliance’s Li Andersson (32), Anna-Maja Henriksson (55) of the Swedish People’s Party, Katri Kulmuni (32) of the Centre Party, and the Green League’s Maria Ohisalo (34). All but one are under 35.

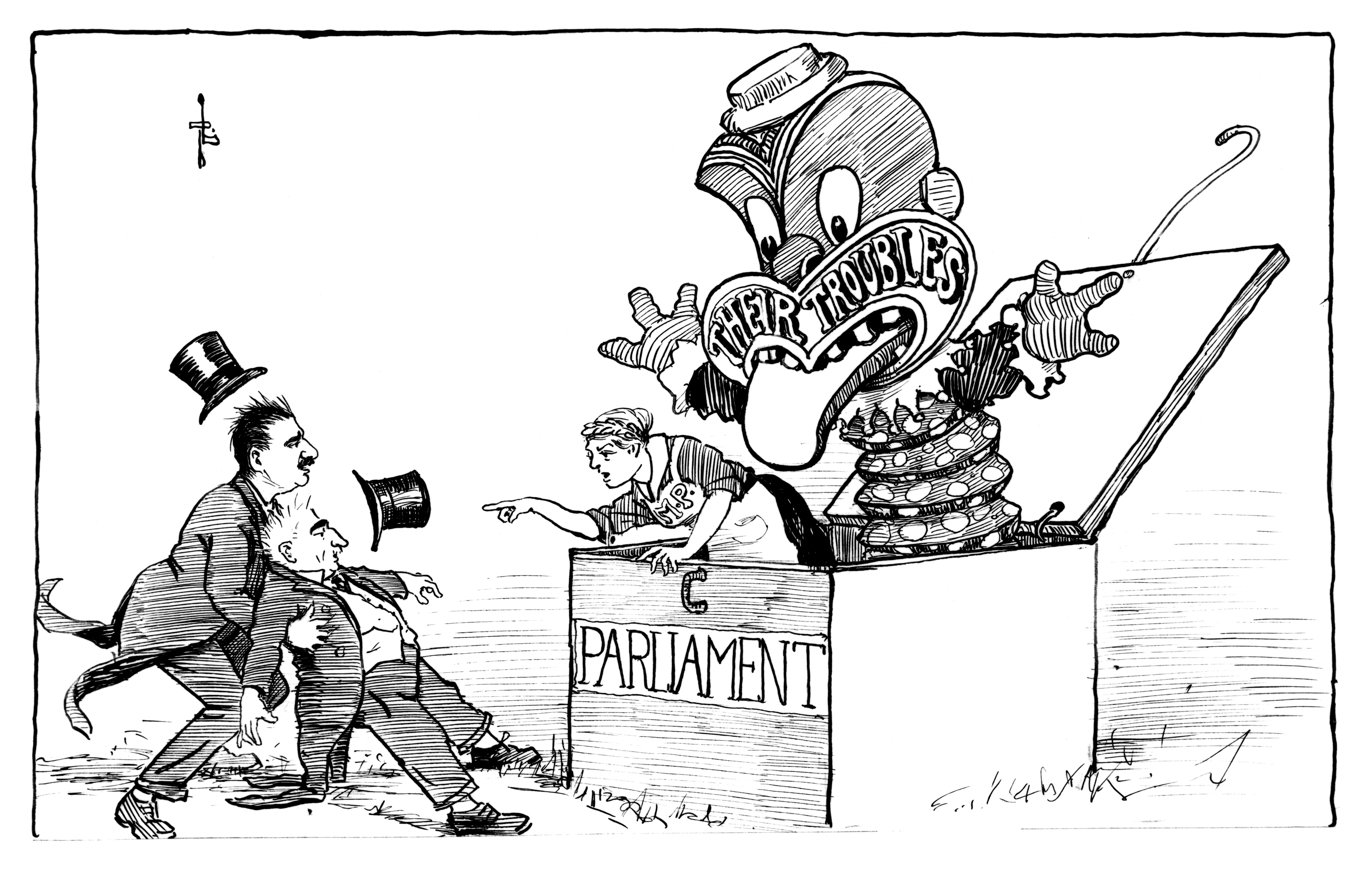

The lady in the case: a 1933 caricature by Trevor Lloyd. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The simple answer would point to trailblazing Education Minister Li Andersson, who has risen like a comet in Finnish politics since being elected chairperson of the Left Youth of Finland in 2011. The Left Alliance traditionally enjoys electoral backing of under ten per cent, but Andersson has consistently been one of the most popular candidates in both local and national elections, only beaten in the 2019 parliamentary elections by populist right-wing demagogue Jussi Halla-aho of the Finns Party.

Andersson has been credited with reinvigorating the Left Alliance, appealing to a young, urban electorate and drawing support and sympathy across party lines. Not long after she became party leader in 2016, both the Green League and the Centre Party elected young women as their chairpersons. The question has always been when, rather than if, Sanna Marin will take on the leadership of SDP.

It would, however, be disingenuous simply to claim that the other parties are trying to copy Andersson’s success. Young women have been on the rise in Finnish politics across the party spectrum. The Green League is the forerunner with a history of six young-ish female leaders. When Maria Ohisalo took over in June 2019, her main opponent was another thirty-something woman, Emma Kari. With the exception of Paavo Arhinmäki, the majority of the top politicians in the Left Alliance are women between the ages of twenty-five and forty-five. When the notoriously male-dominated Swedish People’s Party elected Anna-Maja Henriksson as their first female leader in 2016, it was a sign that something significant was happening. Even the Finns Party have their own ‘Li Andersson’ in ultranationalist and creationist Laura Huhtasaari, a forty-year-old member of the European Parliament and the Finns Party’s 2018 presidential candidate.

What lies behind this explosion of young women onto the Finnish political scene? There is, naturally, not one conclusive answer. One partial explanation is the rise of Li Andersson, who has opened doors for other young women in politics. But part of what made Andersson so popular is a long-standing campaign to get more women elected to local councils and national positions. Gender has, paradoxically, been turned into a political issue precisely by those who feel that gender should not be an issue. For a long time, the stereotype was that politics is done by white-haired men in suits. The recent success of young women must be seen as a push-back against this.

It is probably no coincidence that young women have fared especially well in green, left, and liberal parties with a strong electorate in large university towns, where issues such as feminism, LGBT rights, environmentalism, and animal rights activism, and progressive politics in general, enjoy stronger support than in rural areas. The public tends to associate these matters with women more than with men, even if this has no basis in reality.

A call for change among voters may play a role, too. The widespread discussion about capitalism having reached the end of the road, climate change, the #MeToo movement, and the feeling of a disconnect between (old) politicians and the general public may have fuelled the political careers of young people in general and young women in particular.

But there is also a flip side to this: ‘the glass cliff’. Studies show that women are more likely to be elected to prominent business and political positions in times of crisis. There are a number of possible explanations for this.

One is that women more eagerly accept risky positions as they see themselves as having fewer options for advancement than men. Another is that women are generally viewed as more capable of crisis management – more nurturing and diplomatic than men. But women can also be used as expendable scapegoats when things eventually turn sour.

If we adhere to this theory, it is no surprise that women would dominate contemporary Finnish politics. Not only do we have global crises – climate change, the failing neoliberal project, intensified migration, and the rise of the far right – but Finland has gone through a turbulent period. The previous, right-wing government planned upheavals to the Finnish welfare state, including a de facto privatization of the healthcare system and draconian austerity measures while flirting with the extreme right. The current government has been steadily rolling back the majority of these reforms.

The Finns Party, loved by some but loathed by the rest, is currently the most popular party in the country, and support for the SDP and the Centre Party (the traditional power-brokers) have hit rock bottom, hovering between twelve and fourteen per cent.

Finally, it would be naive to disregard the fact that all four young female party leaders fall within narrow, traditional beauty standards. They are all white, long-haired, well-dressed, of average body size and build, and photogenic. It would, of course, be absurd to imply that these already wizened political operatives would have got where they are ‘through their looks’, but it would be absurd to claim that image plays no part in politics. When the choice stands between two equally competent candidates, our unconscious ‘political reptile brain’ may be drawn to the candidate that we know will look good on Instagram and the covers of glossy magazines. This aspect may be heightened for a party that is struggling at the polls and feels that it needs all the good PR it can get.

Pekka Isotalus at the University of Tampere is quoted in the newspaper Hufvudstadsbladet saying that young women in top posts in Finnish politics tend to have short careers. While it is easy to point at former party leaders like SDP’s Jutta Urpilainen and the Centre Party’s Mari Kiviniemi for evidence, there are just as many counterexamples.

Heidi Hautala was thirty-two when appointed leader of the Green League and has almost continuously served either as an MP or MEP ever since, and is currently vice-chair of the European Parliament. Despite the party’s internal problems, Suvi-Anne Siimes served as leader of the Left Alliance for eight years between 1998 and 2006; Päivi Räsänen led the Christian Democrats for eleven years between 2004 and 2015; and at thirty-one-year-old, Tarja Halonen was elected to Parliament in 1979, became a minister in 1987, the first female president in 2000, and was reelected in 2004 – a successful political career by any standards.

Isotalus is right, however, in pointing out that simply appointing a young woman as leader has never saved a faltering party. Li Andersson is not popular because she is a young woman, but for being one of the most skilled, approachable politicians in modern Finland. That the Left Alliance has halted its decline, and even turned its polling numbers upwards, has less to do with Andersson than is generally claimed, however. The party has gone through long, painful reforms starting long before Andersson became party leader. The Green League, on the other hand, has a background as a democratic youth movement and, as such, has always been highly adaptable and open to change.

With this in mind, it is clear that neither the Centre Party nor the Social Democratic Party are going to solve their current problems just by appointing new, young, female leaders. They have both been plagued by decades of internal strife, backstabbing and factionalism, often involving male party grandees pulling strings backstage. The Centre Party has even led the most right-wing government in the history of Finland and been a part of the left-wing government striving to undo those same reforms. This speaks to the split within the party and its reputation as a gang of turncoats mostly interested in gerrymandering election districts to suit its voter base than anything else.

There’s even a saying in Finnish, ‘Kepu pettää aina’, loosely translated as ‘The Centre Party always disappoints’. The SDP, on the other hand, has been marred by warring unionist interests and strife between left- and right-wing social democrats as well as between liberals and conservatives. Strong unofficial networks and hierarchies have paved the way for nepotism and a resistance to reform.

According to recent election results, the SDP barely registers as an alternative with young voters. The party’s surprising 2019 election win had more to do with the extreme dissatisfaction with the previous government, and the fact that four parties finished neck-and-neck, than any real change in the SDP’s popularity. Now in power, its polling numbers are down to record-low pre-election ruts.

Perhaps Sanna Marin can boost these numbers momentarily, but it is now three years to the next elections and, like other Nordic counterparts, the Social Democrats of Finland need to take a long and hard look in the mirror if they want to remain in power.

Published 2 January 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Janne Wass / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Loneliness is a growing health crisis, and gender norms make men more vulnerable to digitized isolation. An ever-more frictionless online experience erodes young people’s capacity to tolerate frustration and establish lasting ties.

As propagandists of a patriarchal order, tradwives perpetrate harm. But harm is being enacted on tradwives too. So why do some feminists see tradwifery as self-empowerment?