Let’s start by recapping how after almost 50 years, abortion once again became a matter of US state law. On 24 June 2022, the Supreme Court of the United States delivered its split opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overturning Roe v. Wade, a 1973 decision that created a federal right to abortion at 24 weeks. A judicial decision that pro-life activists had mourned with a demonstration in Washington every January 22 was eviscerated. Trigger laws and pre-Row zombie laws stripped women of their right to an abortion and created harsh new penalties for anyone involved in the procedure.

In the months after Dobbs, abortion services and other procedures that ended a pregnancy that threatened maternal health or protected victims of incest and rape became barely accessible in half of the states. When clinics closed, economically marginal women as well as men lost access to a range of reproductive services. Although the cost of raising an additional child is one reason why people choose abortion, no state banning abortion has come up with a plan to support larger families throughout the life of a child.

Furthermore, many physicians are afraid to perform life-saving operations that imperil a pregnancy, out of concern that they will be subject to felony charges and fines. As a result, in some states, women have been forced to carry unviable or dead foetuses to term because medical facilities are unwilling to test the law. Conservative politicians have claimed that things are now as they should be, since Roe foreclosed states making their own decisions about whether to reform or eliminate their abortion laws.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the 2024 election. As it turns out, Americans of all political persuasions want to make their own decision about whether to have children. A year after Dobbs, 34% of Americans wanted abortion to be legal in all circumstances, and 51% wanted it to be legal with some restrictions. A great many people in that 85% are the Republican and independent voters that any GOP candidate will need to beat Joe Biden in November 2024. They are the voters that the GOP is losing in key elections and referenda, even in red states.

But the idea that restoring Roe would also restore reproductive justice relies on bad history. The two were never the same, and the right to abortion is just one piece of the puzzle we call reproductive rights. To understand that is to understand a bigger failure in twentieth-century feminism: that mostly white and middleclass pro-choice activists failed to connect with the needs of American women, largely poor and of colour, who had been involuntarily robbed of their fertility by deceit and by design.

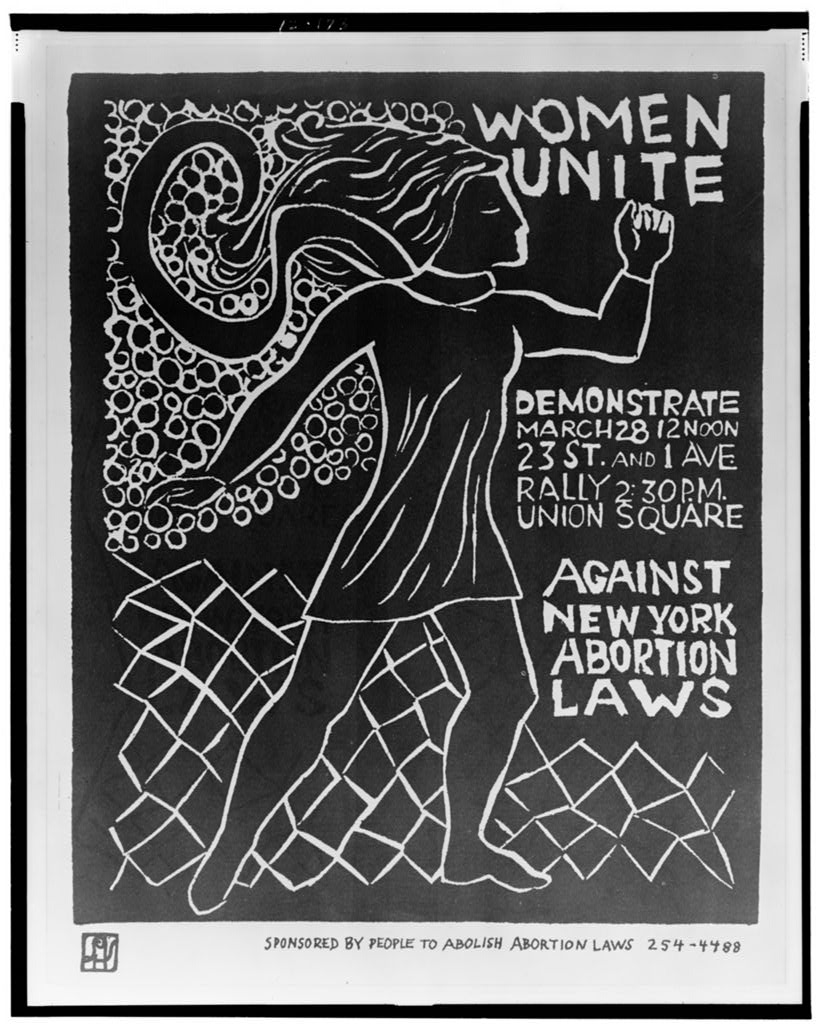

Demonstration protesting anti-abortion candidate Ellen McCormack at the Democratic National Convention, New York City. Image by Warren K. Leffler via Wikimedia commons.

That story takes us back to the states, specifically to New York, a state where abortion was decriminalized in 1970, but also where thousands of women of colour in custodial situations, on reservations, disabled, and on welfare were sterilized. It was a state where women mobilized powerfully for the right to abortion, but also one where a larger and more diverse movement extended the fight past Roe for the right to have babies.

‘It was only after I lost her that I realized how much I had failed to learn from my mother’ writes historian Felicia Kornbluh in A Woman’s Life is a Human Life: My Mother, Our Neighbor, and the Journey from Reproductive Rights to Reproductive Justice (2023). Why was she so passionate about reproductive rights? As it turned out, Kornbluh’s mother, Beatrice Kornbluh Brown, a lawyer, had not only been part of the long struggle to decriminalize abortion in New York state, she had drafted repeal legislation on which the 1970 bill was based and persuaded a lawmaker to promote it. That state-by-state campaign long proceeded and was prematurely cut off by the decision in Roe v. Wade.

When Felicia Kornbluh dug into parallel political activism to end sterilization abuse and transform a medical system that hurt women, she discovered something else. Helen Rodriguez Trias, the physician who had spearheaded these reforms and founded the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, or CISA, had lived across the hall in their New York apartment building. A Woman’s Life is a Human Life tells both these stories in a post-Dobbs world where we are fighting for reproductive justice once again.

Felicia Kornbluh, welcome. First of all, I loved this book, and it taught me so much about the broader terrain of reproductive rights way beyond abortion. And I wonder if you could tell a bit about the story of the book and how you came to write it.

I’m glad that it said some things to you that were beyond abortion rights, because I think that’s what we lose. The book starts with my relationship with my mother, who was herself an abortion rights activist. She died in January 2017, in a very tragic way, from a stroke during my nephew’s bar mitzvah. It was at that ceremony that my other family members, especially my dad and my sister, started talking about my mother’s role in legalizing abortion in New York State, which is something I really hadn’t known.

It was the worst kind of cosmic joke. I am supposedly an expert in the history of women and gender and sexuality and the history of law and social movements. It turns out that my mother, who never regained consciousness after this event, was a pivotal player in a particular moment in the history of abortion rights. That was the poignant start of the book. Then I started to research the abortion decriminalization campaign that she was a part of both in New York and nationally.

Our next-door neighbour Dr Helen Rodriguez Trias had unfortunately died by this point. She was really an unsung hero of modern American women’s history. She was the leader of the anti-sterilization movement that emerged after Roe v. Wade, consisting of a group of women of colour and leftwing women in the feminist movement. They immediately saw that Roe v. Wade wasn’t enough. It wasn’t enough to protect abortion rights constitutionally. It still didn’t cover the needs of everyone, especially not Puerto Rican women, Latinas or Latinx people, black women in the South, low-income women everywhere in the United States, women subject to sterilization abuse and those who had access only to the worst health care.

So after abortion was decriminalized, there was a national push to change the guidelines around sterilization. That becomes a broader understanding of what people really need to have reproductive choices and to have reproductive freedom in a meaningful way. This is the second movement whose story I tell.

I like the phrase reproductive choices and reproductive freedom. I want to go back to one of the first words you used, which is decriminalization. Can you explain why organizing at the level of the state for decriminalization was a prequel to the Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade?

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century America, when we were still a British colony, and after the American revolution, the here was no legislation at the national or at state level that governed abortion. It wasn’t in the legal code at all. The only law that there was around abortion was what’s called common law. A body of law was inherited from England and then changed in a variety of ways after the American Revolution.

The common law was very generous and loose in the way that it treated abortion. It said that it was no crime at all before what was called ‘quickening’, about two thirds of the way into a pregnancy when the pregnant person can feel the foetus and move, being quick within their body. They couldn’t prove that someone had had an abortion after this, because it was up to that person who was having the pregnancy to say, yes, it moved or no, it didn’t move. But in the nineteenth century, it gradually became a crime. There was a process of criminalization that happened at the state level. New York State was one of the very earliest at the end of the 1820s. After World War Two, when people saw the tragic effects of abortion being illegal, they understood that they needed to undo the process that had turned it into a crime and started to organize.

The vehicle for turning abortion into a crime was state level law. In the ’50s, ’60s and 70s, the campaign was to go to the states and say: ‘look, we have to unwind what was done in the nineteenth century. We have to decriminalize.’ A national movement started all over the country, which became very militant and very well organized. That became the movement that put the abortion issue on everybody’s radar and ultimately led to the pressure that caused the Supreme Court to rule in Roe v. Wade and say that abortion in at least most of a pregnancy is constitutionally protected.

There is a common belief that wealthy people could get abortions and poor people couldn’t get abortions. In fact, your book really shows that lots of people could access abortions, but they weren’t necessarily safe and they weren’t necessarily affordable. Could you talk about how women got abortions before it was decriminalized?

There were a variety of ways. I think sometimes we overstate the impact of law alone, because there were people who provided abortions that were illegal or were sort of in a grey zone, who were very skilled. We know from people’s memoirs and from other kinds of records that there were abortion providers. Midwives, medical doctors and nurses were providing abortions all through the period when it was a crime. But there were people who were not skilled, who were hurting people. They were either just trying to make a buck or just didn’t know what they were doing.

The abortions that were legal were ones that were provided under what were called ‘therapeutic exceptions’. Somebody could make the case to their doctor and the doctor could in turn make the case to the hospital governing board that somebody really needed an abortion for the purposes of their physical or mental health. There was s a much larger group of people who were able to have those legal procedures than we usually think. Even at the height of the so-called ‘illegal abortion era’, there were people having abortions. It was kind of what we see today, in a state like Texas, where they have this exception that you can get an abortion if the pregnancy is really endangering your health. Except today, it is not working at all..

While in the Susan Brownmiller archives researching my biography of her, I found a scrap of paper on which she had listed the cost of the various things she would have to pay for to get an abortion in Puerto Rico. Women went abroad to get abortions too. In total it came to about $700, which was equivalent to a little over $2,000 today. So even a professional woman would have difficulty paying for illegal abortion out of the country. But let’s roll this back a little bit. Can you describe what it meant to decriminalize in New York state? Who drives that? What’s the role your mother plays in it? And how does it pass?

First of all, it was a historic bill. It was only one state, but it was the state in which the nation’s media were headquartered. Everybody around the country knew that this was happening. This was a campaign that spurred national organizing. The organization that used to be known as NARAL (National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws), today called Reproductive Freedom for All, comes right out of this fight. . The New York effort to repeal the criminal abortion law was the first test case that NARAL organized around.

The campaign grew out of three different but related sources. One was a liberal movement within the Democratic Party that, much like today, was trying to pull the Democratic Party to the left and make it true to its claims of being a liberal party. Trying to bring it back to the era of Roosevelt in the ’30s, with labour rights, civil rights, including Black civil rights in the South, and women’s rights.

There was also a group of people whom I call population control advocates. People who favoured legal abortion and contraception for reasons that we might find problematic today. They were looking abroad, at poor countries, and trying to provide contraception for people with very low income. They viewed abortion as a way to help poor people, but also to prevent poor moms from having more kids. They were a part of this coalition. We have to be honest about that.

Then there were the feminists. My mother was one of them. She was what I would call a liberal feminist, meaning that she really believed in civil rights and equality. And that’s what drove her into the movement. She was an early member of the National Organization for Women, which was a women’s civil rights movement that fashioned itself very, very much in mould of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), which had just recently won black civil rights in the Supreme Court.

Abortion gets decriminalized around the nation because of the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade. But there’s this other path that the legislation campaign could have gone down, which is a state-by-state battle, which is where we are now. What was the strategy and why did it work?

I think it is a do everything strategy, really. In addition to the liberal feminists, there were also more radical feminists, people who were engaging in the kind of direct action that we associate with the 1960s. They were shutting down hearings, shouting down procedures and courtrooms when doctors were being prosecuted for providing abortions. They were marching through the streets of Manhattan. It was a do-everything strategy.

There was lobbying, there were petitions, there were hits on local legislators. When they came to talk to their constituents, there would always be an abortion advocate there. There were demonstrations in Albany, the New York State capital, where the votes were going to be; there were demonstrations in Manhattan, where there was a critical mass of people who were in favour. There were speak outs where people were finally telling about their own experiences of abortion, whether legal or illegal. They did everything, used all available strategies and built a coalition with anyone who was willing to be part of it, including the clergy and religiously motivated people who had a humane objection to some of the effects of the criminal abortion laws.

They managed to transform the Democratic Party just enough. There were just enough Democratic Party legislators who were willing to vote in favour of new abortion laws and were able to defy the very powerful Catholic Church, alongside some liberal Republicans who had been favouring this all along.

There was deadlock until finally one member of the state legislature, George Michaels, changed his vote under pressure. He was a Jewish Democrat from a heavily Catholic upstate New York district, who knew he was going to lose his seat as a result of voting for this thing. But he did it anyway because he had been pressured by a liberal Republican feminist. You don’t see those very much anymore. He had really been put to the line by her, and also by his own family, who had said: look, you can’t be the guy who makes this fail.

Sure enough, Michaels lost his seat. And yet the abortion law in New York was signed by the Republican governor Rockefeller, that came into law. It was enacted. And despite the efforts of anti-abortion people, it remained good law until Roe vs. Wade.

There’s this intersecting problem, though. As Annelise Orlek describes in her book Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty, about the welfare rights movement in Las Vegas, poor women could not get birth control. They sometimes went in to have babies and then the doctor would sterilize them. There are many other circumstances in which largely women of colour are being sterilized without their consent. Disabled people, too, were being sterilized without their consent.

So there’s this much bigger problem than abortion alone, which is under what conditions does a woman have the right to choose to have children or not? Can you talk about how that movement takes off and how it rubs up against the abortion rights movement?

You’re absolutely right. Involuntary sterilization was endemic. Whether we’re talking about Fannie Lou Hamer, who had what was often called the Mississippi Epindectomy, or about Puerto Rican women who had the highest rates of sterilization in the world (over a third of Puerto Rican women of childbearing age had been sterilized by the late 60s), or Native American women, or people who were in some kind of custodial situation, an institution for the disabled, or in jail or prison – all of these groups were subject to involuntary sterilization. They were also victims to what activists at the time called the ‘coercive sterilization’, when the doctor would suggest that you could lose your Medicaid health insurance if you didn’t agree to the sterilization, or other welfare benefits that you really, really needed.

This was happening all the time in the ’60s and early ’70s. It was the troubling side of the increase in access to contraception under the federal government’s Title X program. Because they were Puerto Rican – my neighbour was a doctor who had been raised both in New York City and in San Juan –and they were coming out of the Puerto Rican left, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, they knew all about this issue. People like my mom, who were white and middle class, who generally had relatively good experiences with their healthcare providers, had no idea that it was happening and sort of didn’t believe it. For my mother, abortion was the outlier, it was the one place where her healthcare rights, her reproductive rights were being violated. But for Helen Rodriguez Trias and the women in the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, it was a much bigger problem.

They started by going after the public hospitals in New York City that were sterilizing people and forming common cause with Mexican and Mexican-American women in LA, with Native American women on the reservations and many others around the country. They created a national network against sterilization abuse. And they also started to theorize reproductive rights in a much bigger way and to think in exactly the way you were talking about: what is it going to take for somebody to really have a choice, not just the choice to not have children, but also the choice to have children under reasonable, decent, dignified circumstances?

It is one reason why poor people are still very suspicious about medical care. Some of the women in your book were told that they were going to have tubal ligations, but that it was reversible. Fannie Lou Hamer didn’t even know that she had been sterilized, as Keisha Blaine writes. She went to a doctor to find out why she couldn’t conceive. She’d been trying for 15 years and never been able to have a child. And it broke her heart when she found out that this thing had been done to her without her knowledge. There’s a lot of trauma associated with involuntary sterilization. Can you talk about how Rodriguez Trias and her organization begin to change those laws to make sure that this stopped happening to women?

They never got a Supreme Court decision. There’s no Roe v. Wade in the area of sterilization abuse, or in the area of reproductive freedom or reproductive justice in general. What they got instead was a series of wins on the regulatory or administrative end of things, which were significant legal victories nonetheless.

In New York, they got the public hospitals to agree to new sterilization procedures. They built this wonderful campaign, what they called an inside-outside campaign, consisting of grassroots demonstrations in the neighbourhoods. But they also had people who were on the committee inside the governing board of the public hospitals.

From there, they went to the citywide level and got legislation through the city council to change the guidelines for every healthcare facility in the city of New York. That’s millions and millions of people, a very important healthcare system in the United States. The Jimmy Carter administration picked up on this and said, okay, well, we’re interested in doing this at the federal level, but you have to organize the campaign to make it possible.

So they organized a national campaign working with all these allies from the reservations and from LA and the Mexican American movement. They had regional hearings all over the country, brought people to every single one, and they testified, protested, wrote petitions and letters. They got the federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare, today known as HHS, to issue new guidelines for all healthcare facilities in the United States that received federal government funds, which was basically all of them.

That’s how they achieved this enormous, enormous win, even though they were not powerful enough to get a bill from Congress, they were not powerful enough to get the Supreme Court to really acknowledge their rights. But that was enough of a win for them. It was a very significant win.

Indeed. And it also brings up the question of what kind of healthcare poor women have access to more generally, right?

It does. Rodriguez Trias was an extraordinary figure. We could all read her speeches and articles today and still learn something and still notice that her agenda is unfulfilled.

In the last of these hearings for the new sterilization guidelines in Washington, DC, she said that there were many forms of coercion. Economic inequality and poverty is itself a form of coercion that prevents people from making the kinds of healthcare decisions and decisions about parenting and about our intimate lives that we want to make. She was putting a universal or single payer healthcare system on the agenda, as a necessary fundament for reproductive freedom.

We would have to do something about economic inequality, we would have to do something about domestic violence and people’s vulnerability, including people who parent, suffer from intimate partner violence, live in unsafe neighbourhoods, or are exposed to police abuse. In her imagination, and the imagination of the people work with, these things were violations or potential violations of our reproductive rights, our reproductive freedom. That agenda is obviously still unfulfilled. But it’s what they really wanted.

As I was reading your book, I thought about how the idea of reproductive justice has to change to meet new circumstances. Today we might say that one aspect of reproductive justice is the right to see your child grow up to adulthood and not be shot down in the street. How would you define reproductive justice today?

I don’t think it’s really that different from what they were saying in the 1970s, because back then people were also experiencing the police violence and the kinds of excesses that we’ve seen more recently. There was no Black Lives Matter movement, but there were a lot of pushbacks against police violence in people’s neighbourhoods. So I think that reproductive justice means roughly the same thing as what these folks called reproductive freedom. And it means that we need the whole thing. If people are really going to make free choices about reproduction, then we need a world in which children can grow up in safety and dignity. That means that no child should ever be hungry; it means that we need massive investments in our public educational system; it means that higher education needs to be accessible despite people’s disparate incomes; and it means we need safe neighbourhoods and decent housing.

All those things impinge on people’s ability to make something like a free choice about whether they’re going to be a parent, when they’re going to be a parent, and with whom they’re going to parent. Those are very personal decisions, but they’re entirely shaped by the social and political and economic context that people are operating in.

One important thing that reproductive justice today really adds – and several of the people I interviewed said this – is the element of justice. I think there’s an idea today, which maybe folks didn’t have in the 70s, that something was taken away, especially from communities of colour. There’s an element of redress or reparation that has to be taken into account. It’s not just that we all start from the same place and all have the same choices. People have been meaningfully deprived of the opportunity to make real choices, and there’s an obligation, a governmental obligation around that.

Felicia, this is my last question: why should our listeners read this book now?

I think people should read this book because reproductive rights are at the centre of our domestic politics. And I think it’s vitally important that we understand both sides of the story. On the one hand, the campaign for abortion decriminalization that started at the state level, and then a move to move to the feds. I think we desperately need to understand how to organize effective campaigns like the ones in the ’60s and ’70s. Because we still haven’t fulfilled the promise of reproductive justice or reproductive freedom. A movement for reproductive rights will only be more powerful when it understands that it’s situated inside this wider agenda. When it is calling not only for abortion rights, but also all of the other things that people need to make genuinely free choices about their reproduction and their intimate lives.

This text is a transcript from Claire Potter’s podcast ‘Why Now? A political junkie podcast’, and the episode ‘Why abortion alone does not make women free’