The crux of different peoples’ history, and of humanity as a whole, is always food and hunger. In the final analysis, it’s the stomach that counts.

In Europe all political thought is imperialist, says Bartlomiej Sienkiewicz. This means that politics as we know it today incorporates the experience of imperial politics from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, when the foundations of what we call “the political” were forged.

Wojciech Przybylski: We are talking about the memory of empires, whose history is inscribed in European political culture. We always criticize empires, when in fact Europe was built on them. How do we come to terms with this imperial heritage and, secondly, how has it shaped Poland’s political culture? That is our starting point. Would you say there is any point in politics that are not imperial by design?

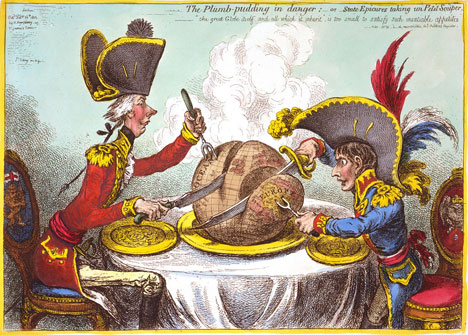

James Gillray’s “The Plumb-pudding in danger; or, State epicures taking un petit souper…”, 1805. Photo: Library of Congress. Source:Wikimedia

Bartlomiej Sienkiewicz: In the Polish consciousness, there is this conviction that the Russian Empire fed on Poland during its expansion and that this allowed it to come into being. Wojciech Zajaczkowski, in his book “Russia and the nations”, presented an entirely different perspective, previously unheard of here in Poland. According to him, Russian imperialism began with the seizure of Kazan, the moment when Russians came from the northern forests, breaking a certain historical, cultural and economic continuity of the Great Steppe. Following Lev Gumilev, one can say that the peoples inhabiting those areas had been part of the world’s longest lasting civilization up to that moment – 2000 years of uninterrupted history. It was the seizure of Kazan and the disruption of this nomadic continuity that actually created the empire, provided it with resources and allowed Russia to control trade routes. Poland was the dessert, not the main course.

And here we are speaking in Warsaw, where the seat of government is located on the former site of the Leib Guard barracks and where what is now the Presidential Palace was built for general Zajaczek, the imperial governor in Warsaw. These real traces of imperial presence in Poland have been completely forgotten. Polish thinking about empires is marked above all by the fear of oppression and it is always tied to trauma and the ultimate shame: the loss of our statehood due to its self-disintegration. Carl von Clausewitz wrote about this, as did others, but we have not accepted it or even acknowledged it.

To explain this difference in perspectives, I would suggest the following example. Perovski, a favorite of Nicholas II, was the governor of the Orenburg line, today’s North Kazakhstan. In one of his letters to Nesselrode, or maybe to Nicolas II (I don’t recall now), he wrote about Khiva, Bukhara and Central Asia, saying that, indeed, there were “savage” people there and they caused trouble, but it was a territory, which, if they invested in it, would become a commercial part of the Russian country and they would be able to conduct business there. He said this about a gigantic area, inhabited by nomads. From our perspective, this seemed to be an absurd idea. We did not integrate into a unified organism any of the territories subject to the Polish Crown – and if the autonomy of Lithuania could be somehow explained, there is no such explanation for Prussia or for Gdansk, not to mention Courland or Livonia. And yet, 50 years after that letter was written, all that territory had been integrated into the Romanov Empire, becoming a stable and important part of it. This is a way of thinking completely unknown in Poland. The only empire we tried to build was a negotiated one, as with the Union of Krewo and later the Union of Lublin. Paradoxically, the only territory that Poland had conquered by force and absorbed into its own statehood, establishing its own administration there, creating an ecclesiastical network and a network of fortresses, was the Halych Ruthenia under Casimir III the Great. This was our country’s only conquest. If there had been any colonization, it was private, not national.

This is significant because in Europe all political thought is imperialist. This means that politics as we know it today, implemented by countries small, middle-sized or large, incorporates the experience of imperial politics from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. That was when the foundations of what we call “the political” were forged, which always entails a balance between power and weakness, and must be the result of an analysis of your strengths and vulnerabilities against the strengths and vulnerabilities of your opponent. To risk banality: politics without political realism is not politics. You see, all European politics is founded on political realism produced by imperial politics. And this experience is completely alien to Poles.

The last thing I would like to note here is the Polish paradox. We belonged to three empires, each of which was distinct, but all were thoroughly political. It is not by coincidence that Clausewitz treats Russia as a cohesive European country among the family of European countries. For Poles such a formulation is incomprehensible. In our perception of the Russians we like to think of wild Cossacks, dumb muzhiks and civilizational inferiority. Yet Clausewitz applied a political category here. For him there was no doubt that between France and Russia there is no difference in terms of political weight. But there was a visible difference in comparison with the closing period in the history of the First Polish Republic. This was an aberration from the point of view of the forming European politics.

Moreover, this political community of three empires, this political homogeneity in no way translated to the Polish experience continued later. I’m not thinking about amusing examples here, like that of the Polish state establishing a Maritime and Colonial League and collapsing immediately after, which would never have happened to a country that had learned just a bit of conscious imperialism. There were of course attempts at drawing on the imperial heritage, because in 1918 Poland took a lot from the Austrian partition zone, the whole legislative system, and above all, the bureaucratic system. But it was enough for half a generation to pass, 15 years according to testimonies from that time, for this good model to turn into its opposite.

We touched upon the experience of Russian politics understood not only as expansionism, but also as guarding the borders of a community, defending this community to the end. You see, towards the end of the inter-war period, the political in Poland was reserved for a very narrow circle of people, because it was a post-feudal country, with everything this entails. I will not even mention the Prussian system of management and strategic planning, in which Poles also participated, but did not import into Poland. After all, for 40 years we were also part of the great Soviet Empire, and during the last 25 years I have personally encountered people, who had been educated by this empire, by the politics that was characteristic of this empire. These were people who had a few rare traits: a phenomenal ability for management, wherever they were. They learned it in school, in youth organizations, tourist clubs, cycling associations, where the steel was tempered. These were the best ones, who could cope with anything, who were called upon by party or socialist youth unions to complete important tasks. A sort of management scheme had been worked out, which led to the situation where in the beginning of the existence of independent Poland in 1989, a director with roots in the Polish People’s Republic was much more apt in the field of management – having a consciousness of the instruments available and the necessary skills to use them – than the most prominent representative of the opposition.

Another characteristic of these people was something we mentioned at the beginning – they would never forget about the relationship between power and weakness, which is the heart of rational politics. This clashed with the natural impulse we had, stemming from the times of the Solidarity underground, where you did not measure your ambitions against your abilities, where everything seemed possible, and where it turned out that our dreams can determine the political, instead of a rational estimation of strengths and means.

Of course, in a certain part of this post-imperial environment of ours, meaning the Soviet Empire, opportunism was very common. And this is the third characteristic that defines these people. Opportunism, on which every large bureaucracy is based, was inscribed in the Polish People’s Republic. It aroused our anger and rage, but today we should be able to understand that it is also part of every bureaucracy and that this bureaucracy that we have created after 25 years is also by nature opportunistic. Every minister who was in office in Poland knows perfectly well that their greatest problem is administration, which functions according to completely different rules than any political goal of the country that is set in its decision making center and that they themselves represent. It is opportunistic, but thanks to this, it is stable. Thanks to this, regardless of political changes, the interest of the country is carried out. Or at least it should be, in a way much more durable than at the political level.

To conclude, nothing in the Polish political was drawn from any imperial tradition. Why is it so? Why are we so resistant? What antibodies do we have in our blood? God knows, I cannot tell, but this is my diagnosis.

WP: You are in fact referring to the line of argument set forth by Michal Bobrzynski, that during the First Polish Republic the state was internally weak, and thus had to be absorbed by empires. Critics of Bobrzynski would counter that this statehood and its self-governance mechanisms were a good system, which up to a certain point functioned efficiently, and that it was the imperial transgression of the three neighbouring countries which cooperated with each other that destroyed this politics.

BS: I fundamentally disagree with this critique, on two levels. At the material level, politics means creating a system, in which it is possible to realize collective goals, grand or small. Now, I would like to inform you that during the First Polish Republic there was one – literally one – public stone bridge in the country. This was the bridge connecting the fortress of Kamieniec with the town of Kamieniec. This country was incapable of creating any material sign of political unity. You find this in all travelers’ accounts – the condition of roads, taverns, bridges, anything that is a sign of community effort. Even the king’s election – a sacred day in that country – was held in the mud of the Mokotów Field, in tents, like in some nomadic tribe.

The second element is that this statehood was an oxymoron in that it promoted a “private politics”. Where there is “private politics”, there is no politics. It is like a system of politicians autonomous with respect to each other, and everyone from the nobility could be one. They were autonomous to the extent that on their own farms they would establish their own autonomous worlds and allow them to come into contact only when they considered it proper, with a complete disregard for what was happening outside.

The First Polish Republic did not produce a politics, and collapsed much earlier than the moment neighboring empires gained gain enough power and strength to conquer it. A hundred years before its final annihilation, this country did not exist as a state – it was a kind of fiction. It can be very well illustrated by means of a simple thought exercise. Just count for how many years after 1700 Warsaw was not under the occupation of foreign armies. This was a dozen years out of a hundred that followed. So there is no point in talking about an ability to survive. Try as we might to escape the truth, but that statehood, which is in some ways a reason for glory and pride, cannot be a model of the political of any kind, because it is its very contradiction.

WP: Let us return to contemporary Europe. What you are saying suggests that convincing the Catholic Church ten years ago to support Poland’s accession to the European Union, and thus to encourage social support for it, was based on a kind of illusion. The Pope’s metaphor, connecting the road from the Lublin Union with the road to the EU, served to bring crucial social support for this direction. Meanwhile, it turns out that it was a kind of ruse, because Poland needs different standards – not those of a negotiated empire, but rather those that are the heritage of empires.

BS: Of course. There can be no equality here. There are centers of civilization and there are peripheries. The peripheries became peripheries as a result of either conquest, or their own weakness, their inability to join the center at the right moment. There are no exceptions from these rules. Of course, it is pleasant for us to say “from the Union of Lublin to the European Union”, but from the point of view of our history this is fiction, fantasy, useful perhaps, but untrue. The Union of Lublin did not give this country the power of the political, in fact, in my opinion, on the contrary, it took it away. The EU in turn, gives us the power of the political, transposing legal solutions and knowledge, which are the heritage of a completely different political consciousness.

I will give you an example described by Jacques Le Goff. Imagine we are in thirteenth century Bruges or Ghent at the city market. The historian enumerates how many stamps were required for one bale of cloth to be allowed into trade. Imagine that you had to have nine different stamps, from different guilds, municipal authorities, and other institutions for this bale of cloth to be in the stall – and here we are at the roots of the EU. If we complain today about the bureaucratically regulated curvature of the banana, we must remember that the beginnings of this process of regulation stem from that period – this regulation, this guarding of balance in the market and in social and international relations, which are regulated by a number of rules and procedures, and which were not drawn from any metaphysical order. Here the whole nominalist revolution comes into play and all that turned out to be a certain breakthrough in thinking about the vertical structure of the world. Returning to your question – the EU teaches us a certain legacy that stems from a different political tradition – the tradition of empires, and not the nobility’s liberty and anarchy, which devoured our country.

WP: But is the EU creating imperial politics today?

BS: No. These famous books that speak of the EU as an empire are completely untrue. The EU has not yet wiped out the power of nation-states that took shape in the nineteenth century and the power of these countries, measured through the power of their economy, population, cultural and political influence, still exists. Even if we are witnessing a slow departure from the nation-state model, these processes are not strictly tied to the EU itself, but to globalization – to grabbing away from the country more and more spheres, over which it used to have sovereignty. This is not a process that will end soon. This agony of the nation-state will last for generations to come. The heritage brought in by nation-states and empires will remain to have an impact for a very long time. Everyone coming to pay their respects has come far too early. But the EU is not an empire for a very simple reason. However we define an empire, whether we follow Hans Morgenthau or other theorists, we cannot ignore one crucial element. I mean power concentrated in one signature, that decides whether something is an empire or not, and determines, for example, why the US is an empire and the EU is not.

WP: It is surely not the British Empire. Not so long ago, Robert Cooper compared the EU to the Habsburg Empire. The EU is not an empire even in this sense?

BS: Not even in the Habsburg sense. Excuse me, but there is a problem with the Habsburg Empire. It is being mythologized like many other things in history. This was an imperial country with its power concentrated within a caste of officials at the service of the emperor, whose signature decided everything. That it all happened within the limits of a cabinet-parliamentary monarchy – I agree. There is a beautiful text in Znak from many years ago, where Boleslaw Limanowski stated that personal liberty in the Habsburg Empire was much broader than in the Second Polish Republic. These were the words of a socialist, who had suffered a lot at the hands of the Austrian police, but he knew that the scope of civil liberties guaranteed by that country was much broader than in Poland, which was sovereign again. He backed it up with examples. A paradox, isn’t it?

But at the same time, in this empire, that was so liberal in terms of individual liberties, the ability to make decisions, which determine – as one can say following Schmitt – whether something is political or not, this ability was concentrated in a very narrow circle of a few people and fulfilled the very criteria of a decision-making vertical. That Vienna had lived its golden age under the Habsburgs does not mean that it was not an empire. But in the EU we do not have such a solution. In the EU we have the control of nation-states having different potential and differing weaknesses, and we do not have decision-making concentrated in one hand, nor do we have power concentrated in one hand.

WP: So the only empire you see today is the American empire?

BS: Absolutely. Of course, we also have aspiring empires, or countries aspiring to the imperial level. This is certainly China, this is certainly – in a resentful way – Russia, which is trying to recolonize territories on which it grew. In my opinion, Russia will not be able to sustain or carry out its aspirations in the long term, but this does not mean we are not going to have a lot of trouble with this.

WP: So why are we supposed to integrate so tightly with the EU and submit less frequently to the demands of American politics?

BS: You are referring to a situation, where the objective law of history would require us to become another state of the US. This is very logical, but I have limited faith in the objective laws of history. Some patterns we can distinguish, but whether they are inevitable, we shall see in the long run. We have behind us 500 years of intense European experience. Based on these 500 years we can more or less give an account of what European empires used to be, and how they were incorporated into nation-states, along with their political. This direction is clear and we know that those statehoods and nations that failed to do this – lost. And this is an indisputable fact. Whether from this we should draw the conclusion that if the US is an empire then the EU should be their condominium – I have no idea. The future is ahead of us. First, we do not know whether the US will remain in its current shape. Secondly, we do not know how long the agony of European nation-states will take. This may be a long process, and I believe it will be so, but it may also accelerate at times.

WP: But we also have very concrete issues that imply a struggle over power between the United States and the European countries. From this perspective, IT companies, the majority of which are subject to American law, introduce the American cultural form, which defines frameworks for conducting business or politics and changes habits around the world. They also cause anti-imperial resentment. On the other hand, the TTIP free trade agreement, which we, as the EU, are negotiating with the US, will lead us into the arms of a certain kind of historical process of – if I may put it this way – submitting to a specific imperial tradition. Meanwhile, the Polish political culture and habits, which you and I would criticize to different degrees, call us to disagree and defend individual freedom. I have the impression that we are missing something very important here, because we have not yet acquainted ourselves well with the European imperial code, and we are already submitting to the influences of a new one, without giving the slightest thought to our own situation.

BS: This is true. This pertains to spheres that are very soft. US power is not about ten aircraft carriers or the ability to simultaneously conduct two regional wars. This power is about exercising impact with instruments so soft that basically they do not raise any revolt. In this sense it is an extra-liberal empire, and not just a liberal empire. Do keep in mind that in Europe, citizens often revolt against the almightiness of the state in the field of information. They consider that the scope of surveillance of Kowalski or Smith is completely unacceptable, despite the fact that they have no reason to think they are being surveilled. But these same people do not have any problem with giving away all their secrets – personal and other – to a company that acts under the law of a completely different country. Here they have no inhibitions – suffice it to look at any Facebook account. None. How is it possible that in the minds of people, their own country, established indirectly by their own decision, is a larger threat, while a gigantic corporation acting under the umbrella of an empire external to their place of residence is not? I do not understand this. The only thing that comes to my mind is that this happens in a sphere so soft that the traditional criteria of the real world are not being applied here.

The categories of the real world have not been transferred to the digital world. A crime committed on Polish territory through a server registered in the United States is not necessarily a crime according to US law. And as Poland we cannot expect any legal help on their part in this matter. In other words: the jurisdiction of a foreign country stretches over the sovereign territory of the Republic of Poland in such a way that it gives impunity against the authorities of sovereign Poland to people who have protection from an external sovereign. This is a total paradox!

WP: Isn’t this exactly the way imperialism operates?

BS: Pure imperialism in a version so soft that it is absolutely unnoticeable in everyday life.

WP: But you do not feel the need to revolt?

BS: Ah, you see – I keep wondering myself. The part of me devoted to serving my country does revolt, while the Internet user in me does not. I am furious at the situation which my country has to accept, but I have not been boycotting Google because of it. You could say: this is Poland – a specific case. But we have also witnessed the exceptionally interesting operation where the backs of the Swiss authorities and banks were being broken by American diplomacy, American justice, and, to be honest, also the American fiscal authorities. Let me remind you that the Swiss, who have for centuries lived in their independence and enjoyed almost absolute sovereignty in the republican sense, had to agree a few years ago that the heir to assets, held or in any way registered on Swiss territory, has liabilities towards the IRS, if the money comes from the United States. This is the end of the sovereignty of Swiss banks. Switzerland has thus entered the American fiscal system. If this could happen to Switzerland, with all its separateness, tradition and the essence of Swissness that is banking secrecy – protected at least since the eighteenth century – then what can we say about such soft statehoods as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia or Poland?

WP: Is it not surprising then that there is in Europe a current which we describe, perhaps simplistically, as pro-Russian, because in fact its essence is for us, Poles, completely incomprehensible – being an anti-American anti-imperialist and choosing Russia as a lesser evil?

BS: This is a true, but I would like to note that this motivates the supporters of Russia in the same way as the supporters of ISIS or other forms of militant Islam. This opposition against empire, against its actions, forms and lifestyle has been growing from the moment the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood revolted after his stay in the United States and decided that he will not accept such a future for the world. Such is an entirely understandable reaction, one that is more likely to spread than diminish. All Chinese politics is nothing but a very careful process of pulling out, one by one, the teeth of the American empire in eastern Asia and Africa. These processes are natural and have been experienced by all large empires. Their presence, the strength of their impact always caused a reaction, which these empires would overcome sooner or later.

WP: Let us go back to the legacy of those empires that we are dealing with directly, leaving Russia aside for a moment. I am thinking here about Prussia and your evaluation of the situation in German politics. Can we compare the way German politics is conducted today to imperial politics, or see its heritage in it?

BS: Ask the Greeks. Or the Spanish.

WP: Countries in our direct neighborhood submit to German politics completely differently. They integrate economically – much more than we do – and thus submit themselves to rules created by German politics. Am I mistaken?

BS: I am not sure. One third of the Polish economy, of Polish export goes to Germany.

WP: Is this too little or too much?

BS: It’s a lot. When the German economy sneezes, it means real health problems for Poland. We are not integrating with Germany to the extent the Czechs are, but they are also doing it in a strange way. They may be integrating economically, but, on the other hand, the pro-Russian attitudes of their elites are, from the Polish point of view, unacceptable. Are the Germans carrying out the Mitteleuropa project with different tools, using EU structure and being its engine at the same time? Such questions have also been posed. Even if this is so, the profits have so far been symmetrical. Tadeusz Mazowiecki decided at a certain point that the most important issue for Polish politics is to overcome geopolitics and during these 25 years we have succeeded in overcoming geopolitics, but there is no guarantee that the next 25 years will be free from it. For the moment the issue of our fatal location between Russia and Germany, where two equally powerful, potentially predatory organisms are lurking at our borders, has not come up. We are dealing with a great problem in the East, a kind of growing resentment and unpredictability, a renewed attempt at colonialism. And in the West we have a country absolutely equivalent to us in its perception of the value of the international community, which is at the same time the largest European power: Germany. From this neighborhood we are gaining more and more. Germany is for us a kind of support, a strategic depth, they are our partner, even if a difficult one sometimes, and most things that have been built here in Poland after our accession to the EU were at least in a large part financed from money transferred by the Germans. Up till now I have been witnessing a symbiotic arrangement, and not an arrangement that would make us feel we are experiencing German imperial power in Poland.

WP: You have now referred to this imperial power as something negative. Imperial politics does not have your approval, unless it is carried out like present German politics?

BS: We are speaking in Polish terms, which means that an empire is always associated with oppression, but Germany is not an empire. Like all large European countries they have been drawing from their imperial legacy, but there is something missing here. German trade may be conducted on a global scale, but there is no power to sustain it with force or pressure – it is rather the attractiveness of their trade and products. This is not a mechanism that can coerce Singapore or the Philippines into giving this or that form of credit. Figuratively – this is not the British case, where opium is used to increase turnover in China and send ships to make sure the Chinese do not rebel. The Germans do not have such power and as a result they are not able to weave such a network of control, trade routes, access to different services, or such forms of currency play that would, on a global scale, subordinate countries external to the EU. This is not possible. Germany is too weak for this.

WP: Germany may be bereft of this will to power as a result of its post-war constitution, but, additionally, there are a couple of dozen American soldiers stationed in Germany, which also protects us from a return of imperial politics to Berlin.

BS: This is another story. From our perspective we cannot appreciate this great change in German mentality after World War II. This is a change that has not been registered at all in the Polish consciousness. I do not claim that the changes are forever, but this is a completely different Germany, a completely different system of values.

WP: Let us return to contemporary Poland. Will Poland ever become political, and will the Polish state apparatus ever fulfil your expectations?

BS: It takes generations to build the state apparatus. It is a great tanker, and only moving the ship’s wheel to the left or to the right makes it start changing its course after some time. You have, however, touched upon a problem that makes me want to reply with a provocative statement.

Yes, I have been part of this kind of politics. In my opinion, these last seven years of Tusk’s government were a lesson of the political, on our Polish scale. I shall give you one example: the Arab Spring had just exploded and Gaddafi’s regime was beginning to fall. A non-NATO coalition began to form, that is a coalition of countries that would intervene ad hoc in Libya, in the name of… a number of things. Poland was also asked to send its F-16 fighter jets. I don’t have to explain to you that the entire political and military lobby wanted us to fly over Libya. I witnessed a situation, where a careful calculation of power and efficiency had been made, and it was decided that it did not lie in the interest of Poland for us to be flying over Libya, and that all the oohing and aahing resulting from our participation in that mission would not increase the potential of our country – quite the opposite.

In the end we did not fly over Libya. I think that we do not regret it today. This is only one of dozens of examples of decision-making, in which the main criterion was to protect the balance of power and weakness. I have to say that from my perspective this was an incredible experience, because every day I would see that this kind of politics is put into practice in my country, where real decisions are made, with which I can identify, because I understand why they are being made. Sometimes I regret what they are, but I also understand that there is no other way. I mean – I have touched a certain level of rationality that I did not think would emerge so quickly in Poland. Is it possible? Yes, it is. This is all that I can say – what will be next? We will see after the elections. I am anxious about that moment, because we may lose this little rationality that has dominated the political in Poland during the last eight years.

WP: Is it not that when the government changes and things “behind the scenes” change, politics will change too? The former SLD [Democratic Left Alliance] government have sent fighters over Libya with no hesitation.

BS: Elections are about giving power to those who are thought to deserve it. Sometimes it is a better choice, sometimes worse. I think that there is something like collective error. Collective political errors may occur if we have no influence over how most citizens perceive themselves, their country, their surroundings. These three things combine into one electoral act, which can be a mistake.

WP: This is a weak politics.

BS: You say weak. After 25 years you want to have a politics like the French legacy, or that of the former Prussian Empire?

WP: No, of course not. But take Israel, which in a short time has built its own, I would say, arch-politics.

BS: This is a question of comparison. You are referring all the time to statehoods that are, what we said in the beginning, from a completely different order. For us, the right point of comparison is nations and societies undergoing a similar process: Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, southern Slavs, Serbia, the Baltic countries, even Scandinavia in a way, although I would be careful here. If you look at it this way, I do not feel that we have wasted these 25 years, also on the level of hard data, which show us where we were with our GDP 25 years ago and where we are now. Some time ago I wrote a text in which I observed that the Czernin palace in Prague, the seat of the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs is an impressive, imperial edifice, while when you look at this chicken coop made of sandstone at Szucha Avenue, which houses the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, you have the impression that this is like a building of poviat offices, compared to what you find in Prague. The thing is that between the weight of foreign policy developed in this beautiful palace in Prague and the weight of foreign policy developed in the sandstone chicken coop there is simply a huge gap. The centre of gravity is here, in Warsaw – not over there, in Prague.

WP: Right, but political realism requires continuity, and continuity is built with certain symbols, about which you spoke in the beginning.

BS: Agreed. We have no idea whether this continuity will be maintained.

WP: That is why we are building from a pile of stones?

BS: Yes. Taking into account our falls, bankruptcies, wars and poverty we are building from a pile of stones. Perhaps it will work out, maybe not. There is no recipe. A recipe is something more than a mechanism or procedure. It is a bit like Napoleon granting promotions to generals. “Ok, he fought here, he fought there… but is he lucky?” The question is whether we will be lucky, because I have the feeling that, after ten to 15 more years of such politics as we have had in Poland during the last 25 years – even if sometimes it progressed in zigzags –, we will be in a completely different position on this map of power and weakness in Europe. Whether or not we shall have these 15 years – I don’t know. It depends on so many factors that it is impossible to foresee: internal factors, external ones, the economy, other empires. It is impossible to tell.

You are looking for a golden recipe all the time, so that what we have achieved during these 25 years – and, we both agree, it has gained some kind of weight – could certainly be transferred onto the years to come… Nobody will give you this kind of certainty, because this is history, and history is not an area of certainty, but one where – as the author of The Moomins said – “all things are so very uncertain, and that’s exactly what makes me feel reassured”.

WP: But this reassuring feeling cannot last at a time when it just so happens that we are achieving something. And if this government is achieving so much, what I find to be missing is the thing that dots the i’s: planning, but also outlining a certain path, talking about it publicly, persuading citizens, because otherwise, without this internal conviction within the community, a sort of national consensus as to the direction we are going, we will not have these effects that are beginning to take shape now.

BS: I agree. But I am not a good person to talk to about this, because I have a big mouth and I am not an expert in communications.

Published 3 July 2015

Original in Polish

Translated by

Aleksandra Malecka

First published by Res Publica Nowa 30 (2015)

Contributed by Res Publica Nowa © Bartlomiej Sienkiewicz, Wojciech Przybylski / Res Publica Nowa / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The crux of different peoples’ history, and of humanity as a whole, is always food and hunger. In the final analysis, it’s the stomach that counts.

Since the war in Ukraine, the Visegrád Four group no longer articulates a common voice in the EU. Even the illiberal alliance between Hungary and Poland has come to an end. Yet in various ways, the region still demonstrates to Europe the consequences of the loss of the political centre.