When Stalin was Hitler's ally

As Russia revives the tradition of wars of aggression on European territory, Vladimir Putin has chosen to rehabilitate the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as good foreign policy. But why violate now what was for so long a Soviet taboo? Timothy Snyder explains.

As Russia continues its invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin has chosen to rehabilitate the alliance between Hitler and Stalin that began the World War II. In speaking of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as good foreign policy, he violates both the long Soviet taboo and adjusts his own prior position that the agreement was “immoral”. What might he have in mind? What is it about the alliance with Hitler that is appealing just at the present moment? What does this revision of the history of World War II mean as Russia revives the tradition of wars of aggression on European territory?

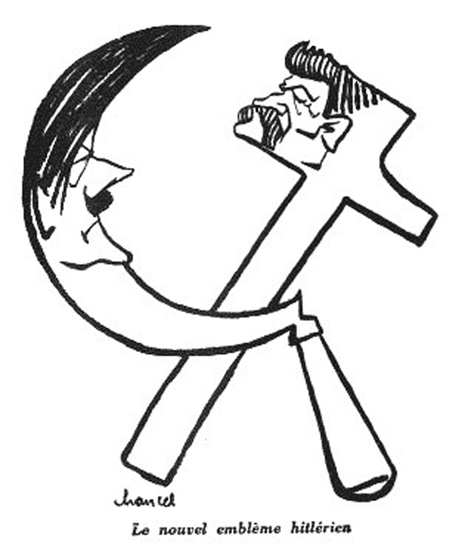

Caricature by Chancel from the French daily, 4 September 1939. Source: Wikimedia

Putin has become an amateur of history, and his recent speeches reveal a kind of wishful reconstruction of the Russian past. Mixing clichés with a good deal of bad faith, he has presented, since his war upon Ukraine began in February, a rather strange history of his own country. He has maintained that Russia and Ukraine are one nation because of a baptism that might or might not have happened more than a thousand years ago in a trading post that was, at the time, a synthesis of pagan Vikings and Jewish Khazars. He presents Crimea, now that it has been invaded and annexed, as eternally Russian, even though its history is a European pageant of cultures. Its Russian character is due largely to the murderous expulsion of Crimean Tatars by the Stalinist regime in 1943. As Belarusian President Lukashenko has mischievously pointed out, by Putin’s own logic of ethnic history it would make more sense to hand over Moscow to the Crimean Tatars than it does to hand over Crimea to Moscow. After all, Muscovy began as a protectorate of the Tatars. Finally, Putin has claimed that Russia should expand southward because there was once a region called New Russia. He gets the borders of the historical district wrong, but this only conceals the deeper error. Expanding Russia into New Russia makes as much sense as England claiming New England or Scotland claiming New Caledonia or South Wales claiming New South Wales. In contemporary history, Russian propaganda embraces simple contradiction and dares the “decadent” West to notice: there is no Ukrainian nation but all Ukrainians are nationalists; there is no Ukrainian state but its organs are oppressive; there is no Ukrainian language but Russians are being forced to speak it.

Even against this unusual and quite spectacular backdrop of historical distortion, President Putin’s endorsement of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is worthy of special attention, especially in Germany. The significance of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact for the history of the twentieth century could hardly be greater. His alliance with Stalin allowed Hitler to fight a war of aggression against Poland with Soviet help, and thereby stands at the beginning of all of the succeeding tragedies of the war, in Poland and elsewhere. In claiming that Stalin was behaving as a reasonable statesman in 1939, Putin is saying that at that moment Hitler should not have been resisted. This is not only a problematic assessment of Soviet foreign policy. It is also a direct challenge to the fundamental myth of the establishment of the postwar Federal Republic of Germany, which is that Hitler should have been resisted in 1939. And there were of course European states that did make the opposite decision at the time: France and Great Britain and most significantly Poland did resist Hitler in 1939. Hitler had courted Poland as an ally for a war against the Soviet Union for five years, between early 1934 and early 1939, and was refused. He courted Stalin for a war against Poland for three days in August 1939, and was accepted with enthusiasm.

On 20 August 1939 Hitler asked Stalin for a meeting, and Stalin was more than happy to agree. For five years the Soviet leader had been seeking an occasion to destroy Poland, and now one had arrived. Stalin understood, of course, that he has making an arrangement to destroy the largest homeland of European Jews with the most important anti-Semite in the world. Stalin had made preparations for the alliance with Hitler, kowtowing like so many other leaders to the Leader’s anti-Semitism. In the hope of attracting Hitler’s attention, he had fired his Jewish commissar for foreign affairs, Maxim Litvinov, and replaced him with the Russian Vyacheslav Molotov. The dismissal of Litvinov, according to Hitler, was “decisive.” It would be Molotov who would negotiate an agreement with Hitler’s minister of foreign affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop, in Moscow on 23 August 1939.

By that time, Jews had a fairly accurate sense of what was to be feared. Five years of accelerating repression in Germany had been followed by shocking violence in Austria during the Anschluss. The destruction of Czechoslovakia in March had also been a disaster for Jews. Czechoslovak Jews had fled the regions annexed to Germany, losing their property along the way. Jews resident in Slovakia lost their citizenship as a new state was created, in alliance with and dependent upon Berlin. In Geneva in late August 1939, where Zionists were meeting at their world congress, the news of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact came as a shock. Everyone present immediately understood what the announcement of the “non-aggression pact” meant: that Hitler had been unleashed and that a war was coming. Chaim Weizmann, the leader of the General Zionists, closed the congress with the words: “Friends, I have only one wish: that we all remain alive.”

This was no empty pathos. A secret protocol to the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact stipulated the division of eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Hitler had the ally he needed to begin hostilities. The east European regions concerned by the secret protocol of the German-Soviet agreement were the heartland of world Jewry, continuously settled by Jews for half a millennium. Once the war began, they would quickly become the most dangerous place for Jews in their entire history. A Holocaust would begin here less than two years later. Within three years almost all of the millions of Jews who lived there would be dead. Stalin famously said that the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was an alliance “signed in blood”. Much of the blood shed in the lands concerned by the agreement would be that of Jewish civilians.

The current press coverage of Putin’s historical turnabout focuses not on the relationship between the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the war itself but on the particular fears of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, the four states than in 1939 were occupied by the Red Army after the pact. On 17 September 1939 Stalin joined his ally Hitler in a military attack on Poland, sending the Red Army to invade the country from the east. It met the allied Wehrmacht in the middle and organized a joint victory parade. The Soviet and German secret police promised each other to suppress any Polish resistance. Behind the lines the Soviet NKVD organized the mass deportation of about half a million Polish citizens to the Gulag. It also executed thousands of Polish officers, many of whom were fresh from combat against the Wehrmacht.

The destruction of the Polish state is remembered in Polish history, understandably; what is often overlooked is the way that Polish and Jewish history must overlap. The Polish citizens murdered by the NKVD, usually reserve officers with a higher education, were killed because they represented the elite of the Polish state. Often they were Jews, whose death at Soviet hands left their families to face the German occupation without them. Wilhelm Engelkreis, a Polish Jewish doctor and reserve officer, was murdered at Katyn. His daughter, writing later from Israel, recalled her childhood despair. Hironim Brandwajn, a doctor, was shot in the back of the neck with his brother officers at Katyn; his wife Mira would die two years later in the Warsaw ghetto without knowing what had happened to her husband. Mieczyslaw Proner, for example, was a pharmacist and chemist and a Jew and a Pole and a reserve officer and combatant. He fought against the Germans in the Polish Army, only to be arrested by the Soviets and murdered with a bullet to the back of the neck. A few months later his mother was ordered to the Warsaw ghetto, from which she was deported to Treblinka and gassed.

In the speech that rehabilitated the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, and on other occasions, Putin has justified the Soviet alliance with Nazi Germany by referring to the complicity of the western powers in the destruction of Czechoslovakia at Munich. Although he is absolutely right that the betrayal of Czechoslovakia was an important step towards the war and the Holocaust, it is not at all clear that the reference to Munich really improves Putin’s case. From all appearances, he himself sees both Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which he tends to group together, as positive examples. The Russian campaign against Ukraine in 2014 is startlingly similar to the German campaign against Czechoslovakia in 1938. It features the use of ethnic nationalism, the invention of historical regions that are only taken for granted after violence (“Sudetenland” and “Novorossiya”), the support of separatists who would never have a chance without foreign backing, and the desire to destroy a European system by destroying a major European state that happens to be more democratic than some of its neighbours.

Of course, in the West, Munich is generally seen as a mistake and a negative example. And Putin’s invocation of the Munich accords is rather incomplete without reference to Soviet policy at the time. France was trying to come to an agreement with the Soviet Union during the first half of 1938, but its interlocutors kept disappearing into the maw of the Great Terror. We will know more about this if and when the relevant archival collections are opened, but to all appearances the Munich crisis was evaluated at the time in the Kremlin as an opportunity to intervene in eastern Europe. Even as London and Paris urged Prague to compromise with Hitler, the Soviets provided indications of their willingness to send their armed forces to central Europe to protect Czechoslovakia – which for simple geographical reasons would have required an invasion of Poland or Romania or both. Four Soviet army groups were in fact moved to the Polish border. On 12 September, Hitler gave a speech about the need to liberate Germans from Czech policies of extermination, and to do away with Czechoslovakia generally. Three days later the Soviet regime accelerated the ethnic cleansing of its own borderlands with Poland. Beginning on 15 September, Soviet authorities carried out swift mass executions of Soviet citizens found guilty of espionage for Poland, most of them ethnic Polish men.

Oral instructions to the local NKVD made clear that “Poles are to be completely destroyed”. Throughout the territory of Soviet Ukraine, Polish men were shot in huge numbers in September. In the city of Voroshilovgrad (today Luhansk), for example, Soviet authorities considered 1226 cases in the Polish Operation during the Czechoslovak crisis, and ordered 1226 executions. In the regions of Soviet Ukraine adjacent to the Polish border, Soviet units went from village to village as death squads in September. Polish men were shot, Polish women and children were sent to the Gulag, and reports were filed later – over and over again. In the Zhytomyr region Soviet authorities sentenced a hundred people to death on 22 September, 138 more on 23 September, and 408 on 28 September. That was the day that Hitler had set as the deadline for an invasion of Czechoslovakia.

The Red Army was standing at the Polish border; and the NKVD had cleared the hinterland of suspicious elements by massive shootings and deportations of Poles, regarded as the enemy nation. But instead the crisis was resolved. At Munich the leaders of Britain, France, Italy and Germany decided that Czechoslovakia should cede the territories that Hitler wanted. This was a shameful action and is remembered as such today not only in Prague but in London, Paris and Washington. Soviet policy during those weeks is entirely forgotten. But the terror and mobilization provides a useful bit of background to Soviet policy after the next European crisis generated by Hitler did create the opportunity for a Soviet invasion of Poland. The Soviet deportations of Polish citizens in 1940 repeated, on a smaller scale, the methods of the Great Terror. Beria, the head of the NKVD, established a special troika to deal rapidly with the files of all of the Polish prisoners of war. He established a quota for the killings, as had been done in 1937 and 1938. In the Polish Operation of the Great Terror of 1937-1938, Polish men had been shot and the families deported to be exploited and denationalized. This was repeated in 1940. If the families of the executed men were in the Soviet zone, they were deported to the Gulag.

After the invasion of Poland, the next major Soviet act of aggression during the period of alliance with Nazi Germany was the invasion of Finland in November 1939. The winter war was a very costly victory for the Soviet Union, although the losses were much greater, in relative terms, for the much smaller target of invasion. A rehabilitation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is also a rehabilitation of that war. In summer 1940, the Red Army entered the three Baltic states, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. After sham referenda they were annexed to the Soviet Union. These three small countries lost tens of thousands of citizens to deportations, including most of the elites. They were declared by Soviet law never to have existed, so that service to the state became a crime under Soviet law. This Soviet idea that states can be declared to exist or not remains in the political memory of today’s elites in the zone affected by the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Because Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were attacked by the Soviet Union in 1939 and 1940, while Stalin was Hitler’s ally, their elites today have also been immune to other Russian propaganda positions, for example the grotesque claim that Russia had to invade Ukraine in order to protect Europe from fascism. They remember not only the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, but also the Nazi-Soviet Treaty on Borders and Friendship that followed, and the sham elections and propaganda in the Soviet zone that so resemble recent Russian actions in occupied Ukraine.

President Putin’s rehabilitation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is certainly directed against the lands between Berlin and Moscow: but in two variants. In the first variant, Moscow invites Poland to play the historical role of Germany, and partake in a division of Ukraine. No one in Warsaw took seriously such proposals. In the second variant, Moscow suggests to Berlin that Germany would be better suited if it acted as a great power, ignoring the new rules of the European Union and following the old rules of the interwar period. Although this would be strategic idiocy for Germany, whose admirable power position depends precisely upon European integration, important German statesmen such as Gerhard Schroeder and Helmut Schmidt have taken meaningful steps towards endorsing this position.

It would be a mistake, however, to imagine that the significance of President Putin’s position is limited to the fate of eastern Europe, important though that is. What is happening is the shift from one possible Russian memory of the war to another, a memory mutation with implications for all of Russia and all of Europe.

Two versions of World War II were always available, because the Soviet Union fought on both sides of the war. From 1939 to 1941 the Soviet Union was a German ally, fighting in the eastern theatre and supplying Germany with the minerals, oil and food needed to make war against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and most importantly France and Britain. During this stage of the war Stalin was eager to please Hitler, and in general fulfilled not only obligations of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the Treaty on Borders and Friendship but also specific requests of his German ally. There was one major exception. Stalin was perfectly aware of the plight of Jews in the German zone of Poland. Unsurprisingly he was completely uninterested in helping them. In February 1940 Adolf Eichmann proposed to the Soviet leadership that two million Jews, the bulk of Polish Jewry, be transferred from Germany to the USSR. There was no sign of interest in Moscow. This was one of the few German requests that was not fulfilled during the period of the alliance.

After Hitler betrayed Stalin and the Wehrmacht invaded the USSR in June 1941, the Soviet Union was suddenly on the other side of the war, and quickly found itself in a grand alliance with Britain and the United States. Soviet propaganda passed over the first war in silence and celebrated Soviet feats of arms in the second. Given the millions of Soviet citizens killed by the Germans this made perfect political sense. The victory in the “Great Fatherland War” became something like a second founding myth of the Soviet Union, and remains so in Russia and Belarus. In this telling of Soviet history, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact had to be denied: not so much because it was as a crime but because it was a blunder. After all, it allowed German troops to approach the Soviet Union well before the invasion of 1941, it aided Germany to become the European power that almost reached Moscow, and it created a false sense of complacency in the Kremlin. Stalin refused to believe that Germany would invade in 1941. He dismissed more than a hundred intelligence warnings of the coming invasion as British propaganda, and was caught completely off guard. In the decades that followed the war, the Soviet Union wanted to present itself as a power that stood for peace. It therefore had to deny that it was one of the powers that began the war.

But as today’s Russia fights a war of aggression in Europe, its leaders seem to be moulding, in ways that might seem contradictory, this traditional emphasis on the defensive war of 1941-1944 with the available alternative, the war of aggression of 1939-1941. Certainly, emphasis on a war of aggression harmonizes much better with the current media climate inside Russia. Between 1939 and 1941, as the Soviet Union presented Nazi Germany in its own internal propaganda as a friendly state, Soviet society ceased to criticize German policies and began to publish Nazi speeches. People in public meetings occasionally misspoke, praising “Comrade Hitler” or calling for “the triumph of international fascism.” Swastikas began to appear on buildings or even on posters of Soviet leaders. A similar level of ideological confusion is evident in Russia today. Jews are blamed for the Holocaust on national television; intellectuals close to the Kremlin rehabilitate Hitler as a statesman; Russian neo-Nazis march on May Day; Nuremberg-style rallies where torches are carried in swastika formations are presented as anti-fascist, and a campaign against homosexuals is presented as a defence of true European civilization. In its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has called upon the local and European far Right to support its actions and spread its version of events. In the recent electoral farces in occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, as in the earlier faked referendum in occupied Crimea, European far-right politicians, including fascists have come as “observers” to endorse the gains of Russia’s war.

Far from being an eccentric detail, these “observers” reveal the fundamental contemporary meaning of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Indeed, it is the Kremlin’s basic alignment with the European far Right against the European mainstream that made the rehabilitation of the Stalin-Hitler pact inevitable, or at least predictable (I predicted it in May). Although Putin would certainly be pleased if actual German or Polish political leaders were foolish enough to take the bait of agreeing to a new division of Europe, he must be satisfied for the moment with the people who have actually responded, in one way or another, to his appeal to destroy the existing European order: separatists across Europe (including the admiring leadership of UKIP), large anti-European rightwing populist parties (of which the most important is the French Front National), as well as the far-right fringe, including fascists and Nazis. They are, for the time being at least, the partners in the Putin’s new Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, because they are the rightwing revanchists that Putin will find in contemporary Europe.

In making his alliance with Hitler, Stalin had a political logic. He imagined that in supporting the Nazi state as it began its world war he would turn the German armed forces to the west, away from the Soviet Union. In this way, the inherent contradictions of the capitalist world would be exposed, and Germany, France and Britain would collapse simultaneously. In his own way, Putin is now attempting the same thing. Just as Stalin sought to turn the most radical of European forces, Adolf Hitler, against Europe itself, so Putin now attempts the same thing with his grab bag of right-wingers. His allies on the far Right are precisely the political forces that wish to bring the European Union to an end, and return Europe to an age of nation states. It should go without saying that this would be a catastrophe for all concerned, including in the end for Russia. But there is an important difference between Stalin in 1939 and Putin in 2014. One can at least credit Stalin for attempting to resolve a real problem: Hitler did indeed intend to destroy the Soviet Union. In allying with Hitler he compromised his ideology and made a strategic mistake, but he was at least responding to a real threat. Putin, on the other hand, had no European enemy. Russian foreign policy has elected to present the European Union as an adversary, for reasons that remain mysterious.

It is unlikely that President Putin actually believes in the various ideologies of the far Right with which they happily consort, at home and abroad, any more than he believes in the ideologies of the far Left, when such groups are daft enough to offer their help to the Russian project. Russia began a war in Ukraine for no reason that anyone is now capable of defining, and thereby began an alienation from the West that, from the point of view of Russia’s basic interests, makes absolutely no sense. The tortured and fruitless search for a strategic justification for this disaster has led to the jettisoning of one of the basic moral foundations of postwar politics: the opposition to wars of aggression in Europe in general and the Nazi war of aggression in 1939 in particular. The rehabilitation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is not the reflection of a clear ideology, but it may be something worse: an embrace of nihilism as a defence of incompetence. To embrace the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact is to discard the basis for common understanding in the western world for the sake of a momentary tactic that can destroy but cannot create.

Published 8 May 2015

Original in English

First published by FAZ, 14 December 2014 (German and English versions)

Contributed by Transit © Timothy Snyder / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Despite the uncertainty of recovery from ongoing war, Ukrainians are confronting Russian destruction and de-construction with daily acts of reconstruction. Marginalized landscapes, histories and stories are being rediscovered through a grassroots resistance founded on loss, where language and naming reclaim cultural foundations.

House keys recur in the stories of Crimean Tatars and Palestinians displaced from their respective homelands in the 1940s, and Ukrainian citizens fleeing Russian invasion since 2014. Ethnographic research and discourses on art and justice show how objects emblematic of home salvage the history of exiled peoples from oblivion.