Who can focus on interior design after the massacres of Mariupol, Borodyanka and Bucha? Ukrainian women tell how their relationships with self-care, beauty and consumerism were changed by the war.

‘I carried a bottle of perfume in my go bag’, an artist from Kyiv told me.

‘After evacuating, my boyfriend said I should buy something to cheer myself up. I approached a shopfront with cosmetics and I got nausea’, a columnist shared.

‘I wear red lipstick, as women did in Hitler’s time’, said a journalist.

‘When I looked in the mirror after two weeks, I did not recognise myself’, confessed a citizen of Bucha.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion on Ukraine, our priorities have changed dramatically. The notion of normalcy has been shrunk, if not cancelled. Media that used to focus on lifestyle, beauty, design and culture, were helpless. Their topics were vaporised by the danger of physical destruction.

We never imagined that daily routine will become such a painful topic. Our everyday discussions about comfortable apartments, tasty food, clothes, the right to pleasure and the right to life itself – these things we took for granted have turned into privilege.

Who can focus on interior design, after Mariupol, Borodyanka and Bucha?

I will tell you a bit about myself first.

After almost a month of living under bombardment, a friend living abroad told me she had bought eyeshadow in the colours of Ukraine. At that moment it occurred to me that I hadn’t touched any beauty products since the invasion began, out of fear and some unconscious beliefs. Once laying on the floor during the shelling I even thought “Well, hardly any evening dress starting from this time will suit me ever”. These unconscious beliefs in my case contains a bit of the USSR approach to upbringing, when since early childhood you somehow internalise the idea: you are who you are in your gloomy grey dress your parents bought on the local Chinese market in the 90’s, and all these flamboyant looks are signs of annoying abundance. With the attacks on Kyiv, this idea made a comeback, Making beauty products seem like a feast during the plague.

I decided to talk to women of different ages and vocations to understand how they cope with the abnormality of war in our everydays. I asked them how they express their femininity and where they feel lies the point where self-care turns into ‘inappropriate whim’, self-centeredness, and where, after all, a sense of guilt creeps in.

‘I’m a creative one, and my sense of style will die with me’*

‘On the second day of the war I was almost cramping with fear, but I stood next to the mirror curling my hair and wearing lip gloss’, a Kyiv actress started her story.

Dad called me and told me that I’d better start packing because I was supposed to travel to my grandpa’s village in two hours. Then dad insisted that I had to take only the most necessary stuff. “Sveta, please, leave the high heels”, he asked me.

Upon reading this message, I was surprised by the details that this person was ready to share. She was also aware of the oddity of her reactions.

I stayed at my grandpa’s place for a week. I had to take a bath in a washbowl because there was neither hot water nor a shower. But I got used to doing it every day. It was profoundly important to me to have smooth legs and a nice scent even under these circumstances. On the ninth day, I arrived in Lviv and met with my friend. She said ‘I knew that even during the war Sveta will look like that”

Many women of different ages and vocations told me that caring for their cleanliness and beauty has helped them maintain some semblance of normalcy. Even in the depths of despair, they try to hide their feelings and are forcing themselves to do something with their appearance.

‘I volunteered in Lviv and delivered hygiene items to the displaced people from Mariupol and Chernihiv. When I had some spare money, I used it to buy face serums for women. That hyaluronic acid, indeed, might seem like a bad joke for someone who is under fire. But for those who survived, it might work as a thread that leads to the feeling that you are a human being. I will never forget the joy of these women, caused by such a little gift’, — another Kyivite cultural worker explained to me.

To survive the occupation, recover and go for a walk with red lipstick on to spite death.

To show that you are alive.

‘I am a great woman and I will not give up.’

‘These damned Russians won’t make me give up on the cologne!’

That’s how beauty works as an injection of courage and aspiration — for those who radiate it and for the people around them. However, sometimes this attitude has its downsides. The aforementioned actress told of it candidly:

There were a bunch of people at the train station where I was volunteering, and we didn’t have enough time to hand out the food for all of them. Despite this pressure, I remember the inner voice telling me to look in the mirror and fix my makeup. There were no ‘racists’ nearby and I didn’t feel the scent of death, as if your only task is to survive, so maybe I’m no expert. But I’m the kind of person that even if a stranger follows me in the night park, I first ask myself whether my lingerie is sexy enough.

Many women will recognise this inner monologue.

‘I haven’t brushed my teeth for three days, that’s how much I didn’t care’

Martial law has triggered mental health problems and body image issues. For such a long time harsh beauty standards were imposed on women, so the idea of necessity of some ‘preparations’ before going out in public — such as putting your concealer on a face — became a part of compulsory hygiene routine. Of course, during wartime one barely has a chance to do it. So things that can rebuild a crucial connection with a human world, made not only with instincts and necessity, but also full of symbolic practices, can at the same time immerse you in the depth of despair.

‘Without makeup, this is not me’, ‘it’s impossible to go to the street like that’, ‘find a mirror and fix your makeup, no matter if its safe or not’, — the insecurities voiced by my interviewees, are rooted in their fears about self-worth. The all-pervasive expectation toward women to present themselves in a particular way, can swell into excruciating anxiety.

In a sense, the war forces you to contend with the question of what makes you you.

Psychologists used to say that either lack of vitality or the powerful will to live are normal reactions to the horrors of war. On the other side, there are those who disconnected from vitality by the invasion. And it can go far beyond makeup or clothes, affecting one’s appetite, libido and overall relationship to comfort.

Surrounded by buildings reduced to rubble, confronting hundreds of people who have gone through hell on earth, one’s anxiety can block even the slightest inclination to hedonism.

‘Consumerism died inside of me on February 24th’

On social media, photos of victims and devastated buildings are side by side with vivid commercials — together they create an abnormal and surrealistic dialogue. As normality dissolves, your personal desires somehow seem like a guilty pleasure.

‘I wear strangers’ clothes from a charity organization and do not care how I look. I’m glad that I am alive and not in the basement anymore’, answered a theatre director from Kharkiv. Currently, she is abroad.

‘On the second day after our trip to Warsaw, mama’s friend asked us to go shopping and to buy a beautiful new dress so we could feel better. I could not believe how fucked up this proposal was’, a producer from Kharkiv commented.

A film producer told she had to visit the Cannes festival along with other Ukrainian professionals in the second month of the invasion:

For the whole first week, I didn’t wear makeup, but sometimes I used cologne, so there could be, let’s say, a scent of normality. Lately, I was on the jury for a film festival abroad where a fancy look is not just expected — it is required. I went shopping because of that and noticed that I felt sick from all those dresses and beauty products. Accidentally, I bought a pair of shoes that were three times smaller than I needed.

Another significant trait is that women were talking about physical changes under the circumstances of war rather often than not.

‘I began to suffer from demodicosis caused by stress, so all the ideas about makeup today are inappropriate’, — shared the film director from Sumy city.

Although pimples seem to be a relatively harmless health issue such a radicalised reality could bring to your life. A manager from Ukraine’s capital, for instance, experienced extraordinary disassociation.

On the first day of the war I stopped feeling my body altogether. I couldn’t really perceive how it feels, how it looks. Often, I’ve been witnessing myself just sitting around and simply staring at the wall. After a couple of weeks, I noticed I do not identify my reflection in the mirror.

I got scared, so I started to get acquainted with myself. For a couple of days I was doing a face massage and a breathing exercise. This brought me back to my body a bit. Once I tried to put on makeup and that recalled such beautiful and warm memories! But this little familiar episode was easily crushed by the news feed.

Today I don’t use any beauty products. But self-care helps me maintain a connection with reality overall.

Telling support from obsession

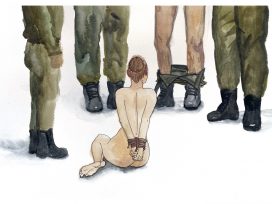

The discussion about the healthy balance between pleasure, comfort and your moral duty is high on the agenda now, and not only in Ukraine. But Ukrainian women have started to see the privilege of beauty from a dramatically new angle. The reports of horrific rape cases add a layer that’s hard to even fathom.

Artwork by Katya Lisovenko

In interviewing women, I noticed that many of them unconsciously outlined a ‘comfort minimum’ for themselves. This minimum is highly subjective, but it helps them to stay sane. Small things can work like transitional objects: your favourite ring, your favourite sweater contain the essence of home, familiarity, and ultimately, one’s own self. This is what a special cologne with a ‘scent of normality’ can offer.

Of course, breathing exercises and a favourite cologne will not alleviate the reality of war. Nor does any advice from friends or strangers. Even those who weren’t raped, injured or attacked themselves face irreversible damage. To support these people, Ukrainian volunteers, NGO’s and the government launched a growing list of services that can help one to cope with crucial psychological issues in the time of crisis. Help24, a service from Stiukist’ Hab or the Peremoga chat-bot are just a couple of them.

*Subheadings are cited from the author’s interviewees.

Published 28 July 2022

Original in English

First published by Gwara Media (in Ukrainian)

Contributed by Gwara Media © Olena Myhashko / GwaraMedia / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The fall of the Berlin Wall, and not the human chain across the Baltics, is emblematic of 1989. But what if this show of unity had become iconic of communism’s disintegration? Could acknowledging Eastern Europe’s liberation positively reframe what Russia otherwise perceives as loss since the Soviet Union’s demise?

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.