Surfing the political segments of the internet, it is almost impossible not to bump into ludicrous clips from Russian propaganda television: one moment you might confront Vladimir Solovyov, the most notable propagandist of Putinist Russia, comparing German chancellor Olaf Scholz to Adolf Hitler in an awkward impression; the next, you might encounter the ‘let’s go full World War III’ escapades of Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of Russian propaganda media channel RT. Alternatively, you could run into the work of more secondary figures, delivering stand-up routines that, to an outsider, might appear unhinged.

Without this contemporary version of Russian serf theatre, performed at the behest of nobles in the eighteenth century, Russia’s war against Ukraine would not be possible on the scale it has been. Putin’s escalation of the conflict via ‘partial mobilization’ and sham referenda, as well as massive attacks on civilian infrastructure have all been consciously coordinated through propaganda activities. Vengeance narratives are pushed on demotivated, or at best apathetic, Russian audiences.

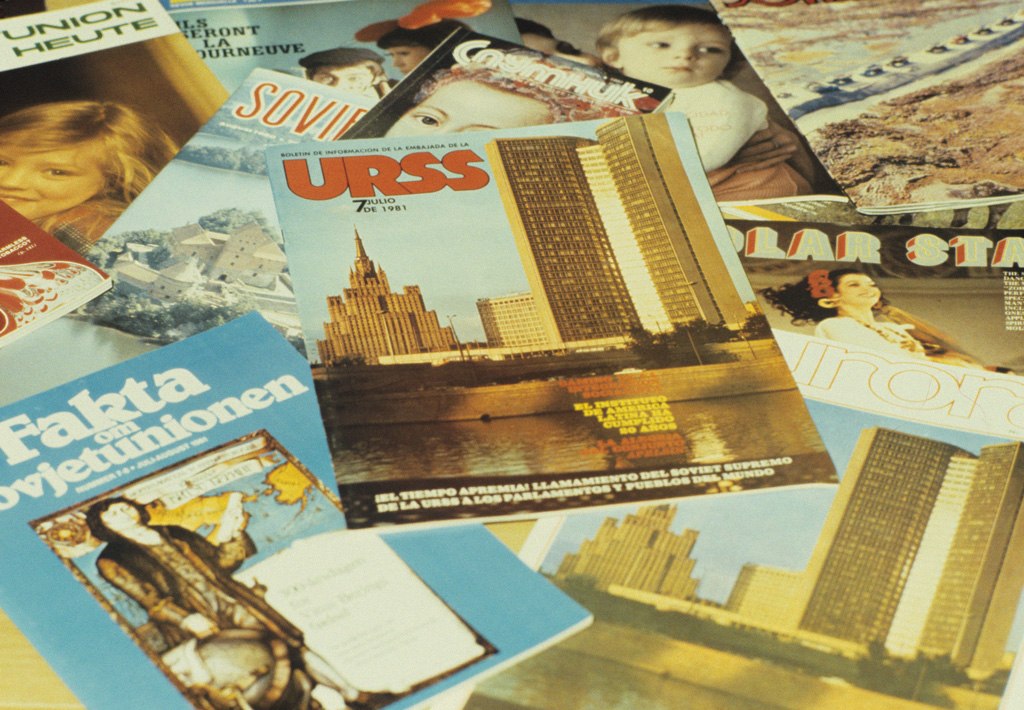

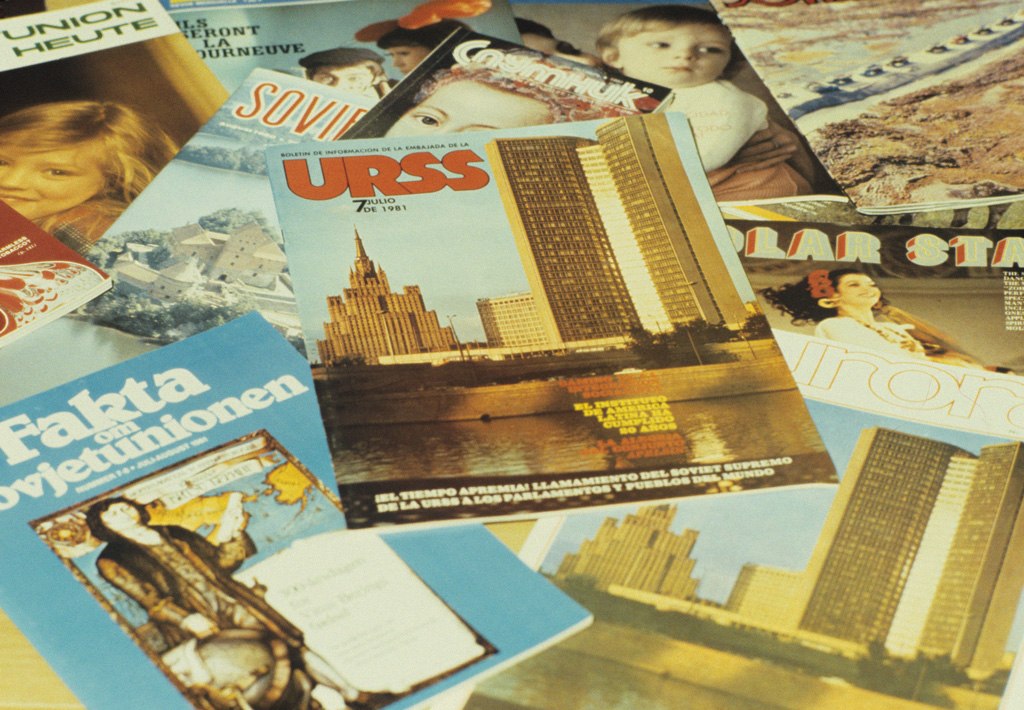

Magazines of Novosti Press Agency from the RIA Novosti archive. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the bizarre and evidently distorted reality conjured by Putin’s media strategists, their propaganda has proved considerably effective even outside Russia. Not in the sense that many people in Europe believe in the Russian message. From a European perspective, Russian propaganda consists of nothing more than blatant lies and deliberate disinformation. The problem is more subtle.

The goal of Russian propaganda is not to convince its audience. It doesn’t sell anything concrete, be that a message, an idea or a proposition. Propaganda sells a structure of feeling; in other words, it sells a vibe. In the case of Russian propaganda, this consists, on the one hand, of great uncertainty as to what is going on, what is real and what is not, and, on the other, of being overwhelmed with conflicting opinions, interpretations and hypotheses.

Usually, it emerges from pundits’ flooding the discourse with unchecked information, provocations, suspicions, conspiracy theories and half-truths, mixed with (why not?) straight truths. It becomes easier for consumers of information to wave a whole topic away than to begin to attempt to unravel this tangled bundle.

Yet while this strategy has facilitated Russia’s launch of the brutal war against Ukraine, it may also be responsible for the political and military defeats it is currently suffering. In the long term, it may prove instrumental in Russia’s painful decline. Reality can’t be distorted indefinitely – not without dire consequences for a state’s executive function.

To understand how this distorted reality has been shaped in the case of Ukraine, let us consider Russian war propaganda in its three distinct phases.

Greatness and humiliation

The first was a continuation of Soviet propaganda. A carefully reframed World War II narrative, invoking the ‘Great Patriotic War’, conveyed a message about the undefeated power and greatness of the Russian army, parasitizing the victory over Nazism, and excluding other countries and nations from it.

This campaign was all-encompassing, filtering through mass media, television series, films, official event communications, parades, and more. The culture sector was riddled with ‘Great Patriotic War’ imagery. The appropriation of the Allied powers’ 8 May VE-Day (celebrated on 9 May in Russia to accentuate the connection) as a potential moment of triumph over Ukraine provided the background for militarization and weaponization.

Even its export variations were under this ‘soft’ militaristic influence. Take, for example, the concept of a new-generation fighter jet, promoted in 2021 via an ironic campaign involving the launch of a cologne with the same scent. Cultural magazines including the British Calvert Journal, played along with this trivializing logic in their reporting on it, effectively downplaying the reality of Russia’s military complex as it prepared for war. The magazine happened to close on 24 February 2022, the day Russia invaded Ukraine.

This narrative was mirrored by a kind of Weimar-ish story, in which Russia was framed as humiliated, encircled and, in the words of prominent Russian foreign policy expert Sergei Karaganov, ‘treated like a defeated power, though we did not see ourselves as defeated.’

There is an obvious contradiction between these narratives of greatness and humiliation. Yet propaganda is necessarily incoherent. In psychoanalytic terms, it is precisely this combination of conflicting self-representations that creates a symptomatic problem, resistant to conscious reflection by society at large.

Eight years of mind games

Such conditions provided a backdrop for the development of other distorted narratives. The second phase of propaganda began with the emergence of a neo-Nazi narrative. In recent years western states, including Italy, France, Sweden and the USA, have all seen a rise in right-wing extremism. This was of minor interest to the Russian state as, for some reason, was the case with the rise of militarized Nazi movements within Russia itself.

With Ukraine, it was another matter. Starting with the Maidan Revolution of 2014, the country has dominated Russian political discourse, constantly being branded a corrupt, neo-Nazi ‘failed state’, full of far-right radicals conducting domestic terror against the Russian-speaking population. From here, the trope of ‘Russian speakers needing Russian protection’ developed.

In parallel, the Russian media machine, partly relying on proxies and ‘useful idiots’ from the West, took efforts to portray the EU as, on the one hand, a weak institution going through a severe crisis, and, on the other, an aggressive apparatus of the US-led West, striving towards world dominance at the expense of other nations.

This messaging was accompanied by a constant pitching of Russian military technologies, nuclear weapons and ‘victories’ to the public.

The launch of a full-scale invasion of Ukraine was thus prepared with almost eight years of mind games. It was then that phase three of Russian war propaganda began.

Liberation by terror

When Vladimir Putin launched his ‘special military operation’, he expected a quick and decisive victory. To quote Solovyov’s propaganda, delivered on television two days prior to the invasion, ‘We only need to move an eyebrow, and Kyiv is ours’. Yet, the resistance shown by armed forces and ordinary Ukrainian people ready to fight for the country provided the first crash test for Russian leaders’ plans.

It is possible that the Russian leadership, as well as their armed forces, believed that they would be able to take Kyiv in a couple of days. The idea, however, that Ukrainian people would be willing to meet the Russian troops with flowers, celebrating the long-awaited ‘liberation’ was simply a lie. According to Ukrainian intelligence, polls conducted for Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) showed that large sections of the Ukrainian population were prepared to resist invasion.

Nevertheless in a speech on 25 February, Putin claimed that most Ukrainian military units had been reluctant to engage with Russian forces and only right-wing formations had tried to resist. He also referred to the Ukrainian government as a ‘bunch of neo-Nazis and drug addicts,’ making use of Russia’s old, familiar talking points.

In an attempt to manifest this narrative as reality throughout March and April, Russian propaganda denied basic truths: not only did the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians not want to be a part of Russia, but nor did they need ‘liberation’, especially when what goes by this name showed its face in genocidal ambitions, as in the case of political strategist Timofey Sergeytsev’s handbook. Published by the Russian state-owned media outlet RIA Novosti, this constituted a guide to destroying the Ukrainian nation after a successful future occupation of its territory by Russia.

As atrocities on civilians were being revealed in Bucha, Sergeytsev’s programmatic text directly demonstrated that Ukraine was dealing not simply with some military excesses by the Russian army, but with a methodical strategy of executions and terror.

This campaign came at a peak moment in Russian propaganda’s detachment from reality, and the official reaction amounted to outright denial of Russian genocidal war crimes in Ukraine. Conspiracy theories proliferated in Russia’s official and unofficial communications channels concerning who staged the Bucha massacre and why. Television propaganda continues to convey these messages to the Russian public today.

A series of crumbled myths

As already suggested, no distortion of reality can last forever without severe consequences on the ground. The Russian army has faced severe resistance from the Ukrainian people, proving unable to meet its ‘special military operation’ goals, and suffering from enormous loss of military reputation due to looting, war crimes, and the exposure of terrorist tactics used on infrastructure and civilians. Narratives of an invincible army of ‘liberators’, fighting the corrupt West and its proxies have utterly failed to match the reality.

The Ukrainian counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region exacerbated Russian propagandists’ problems. What story could they tell now, when the disastrous situation became completely self-evident?

The response was to suggest that the losses were not down to Ukraine, but rather a loosely defined Other – the USA, NATO, Europe, or, as Putin put it in his 21 September address, ‘the collective West’. While such a conflict was previously only referred to obliquely, often in cultural terms (for example, as a clash of ‘traditional’ and ‘Western’ value systems), Putin now speaks of direct confrontation.

This move was not unexpected. While Putin may not have framed things as such, Russian propagandists have been selling this narrative for quite some time. It has proved useful in disguising and justifying both the real problems the Russian army faces on the ground, and the more fundamental problem: that this is an unjust war of aggression against Ukraine, an attempt to destroy the state and the nation itself.

Nevertheless, certain actors in Putin’s propaganda theatre said what they really meant. Prior to Putin’s own announcement of the 21 September mobilization, Andrey Gurulyov, State Duma Deputy said on Russian television: ‘It is clear to me that today’s decision is the beginning of the end of Ukraine. That’s it, that nation no longer exists.’ And after the war strategy changed in October (when Russia began systemic attacks against Ukrainian civilian infrastructure using rockets and drones), Russian officials and propaganda spokespersons openly declared a genocidal intent to freeze Ukrainians to death during the coming winter. Such statements make little sense if the idea of a ‘great war against the West’ is taken at face value.

Blocked fire escape of Russian TV building in Moscow. Photo by Gennady Grachev. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A long line of myths has crumbled during this war. First, the pragmatic European logic that Russia would never start a full-scale war was blown up, then the Russian delusion that Kyiv would fall in three days. There was also the prevailing myth of an undefeatable Russian army, heir of the Soviet armed forces. Now, the myth of a weak Europe that chooses money over human dignity and the rule of law is also being challenged.

In their dealings with Russian propaganda, western journalists and policymakers often call its products ‘disinformation,’ yet the term is a somewhat misleading one. It is possible to provide false information about something when there is prior agreement on the basic structure of reality and facts. Russia, however, uses narrative warfare to recombine these facts and to deny the common reality. In the words of Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov, ‘the entire world had better face this new reality.’

Russia needs a reality check, on both a military and political-discursive level. First, the nation must accept Putin’s military defeat, however risky for the ‘business as usual’ European logic such recognition might be. The reality of the battlefield is, in a sense, more real than reality elsewhere, more resistant to manipulation when it comes to merging with the media spectacle.

This means that any external propositions to help Putin save face are, at best, short-sighted. If Russia fails to emerge from its echo chamber, being helped instead to go deeper into it, we will likely see the return of similar, unprovoked aggression later.

Only after confronting realities – first military, then political and social – could a reconfigured Russia (perhaps some post-Russia formation or even formations) begin the long process of reintegration into the civilized community.

For Russian society, the reality check would mean giving up the victim-blaming tendencies rooted both in pro-Putin (‘Europeans are guilty because they want to conquer us’) and liberal (‘Europeans are guilty because they do not want to help us’) political discourses. Only after accepting responsibility for what is going on in their country, can Russians start to open the space for action and change.

There is, however, a prerequisite for all of these processes. Ukraine must win the war.

Europe: vision over pragmatism

The war in Ukraine has also meant a huge reality check for Europe, proving that a politics of decisiveness represents an effective tool. Take, for example, the case of European policies towards Ukrainian refugees and displaced persons, which were executed lightning-fast, without bureaucratic complexities. It is evident that in the current security and political climate, Europe is still too far from establishing efficient technocratic processes that circumvent partiality and action bias.

Perhaps counterintuitively, a reality check for Europe should also mean the return of European ambition. For a long time, Helmut Schmidt’s motto that ‘whoever has a vision should go to a doctor’ has been the cynical undertone of talk concerning Europe’s future.

This pragmatic attitude had certain positive consequences in economics, the regulatory sphere and overall opinion balancing. But at a time when the basic certainties of European existence are under attack, there is cause to bring vision back to politics.

Here we come to the third aspect of the European reality check, and that is the establishment and cultivation of European values and certainties. While fact-checking, media literacy courses and op-eds might be useful to an extent, they are no major weapon against Russian narrative warfare. Propaganda warfare is not, ultimately, about shaping public opinion; what it does is create uncertainty, disrupt the decision-making processes, and suspend people’s ability for constructive action. Arguments against disinformation are of limited use against the deeper problem, which demands certainties such as the commitment to human rights.

This means Europeans must be ‘ready to be bold’, as was recently highlighted in a speech by EU High Representative Josep Borrel. What, precisely, is the European promise? This should be formulated, stated, communicated and overcommunicated. The whole European model and way of life are dependent on this promise being certain, visible and inspiring.

Propaganda is not all-powerful. It can only work successfully if there is strict control of society and the political situation. In the case of war, the formula is always the same: total dominance and fear. If the goal of propaganda is to create a fog of uncertainty, there should be an island of certainty at the place of its origin. For a long time, Putinist Russia branded itself as such an island: stable, apolitical and immune to perturbations typical to western democracies. When this propaganda image crashes against the wall of reality, it begins to resemble Cinderella’s carriage turning into a pumpkin.

The Russian Federation has lost the initiative and is losing control. Impulsive, rageful attacks against civilians only make the situation worse. The propaganda machine has broken against the wall of reality. But the process of coming to terms with this reality is not finished for Russia. It will be long and painful. This is a war of realities, and it is still going on.