War and digital memory: How digital media shape history

Social media platforms have changed the way that people mobilise and act collectively. But as Kateryna Iakovlenko discovers in the context of war-affected Ukraine, the visual record created by apps like Instagram are forcing researchers to reconsider what constitutes an objective record, a subjective perspective – or possibly both.

Platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have recently demonstrated that new technology can be an effective tool for mobilising people and consolidating support for an idea, sparking off much discussion of the new media, or ‘new new media’, to quote Paul Levinson.1 These platforms have been forging a new utopia, in which grassroots communities can influence global politics. Instagram – a social network whose users post their own photos or those of their products with the aim of sharing, distributing and selling them – has rarely been included among these political platforms. Instagram is regarded as one of the most popular platforms with the fastest growing content, including in Ukraine. For instance, statistics published in June 2017 by the online newspaper Watcher show that the total unique audience of this medium in Ukraine comprised 5.6 million individuals, reaching 6 million by August of the same year.

In his book Instagram and Contemporary Image2 Lev Manovich describes several types of photographic content found on this social network. He refers to one of these types as ‘everyday’ content: posts by ordinary users that depict their way of life and their interests. In this respect, Instagram should be seen as a gigantic digital archive, comprising a multitude of personal archives. Personal pages that are updated online are, in a way, analogous to family photo albums in this digital age.

Instagram enables its users to present themselves and their lives the way they wish to be seen. In this sense, the tool plays a dual role. On the one hand, it makes it possible to shatter myths relating to certain concepts while, on the other, it creates an alternative history, one that often bears little relation to reality.

This raises a number of ethical issues. For example, how are anthropologists and historians to treat this material? To what extent is this kind of material an objective reflection of reality, or does it rather represent a subjective perspective? These issues become particularly relevant when we are dealing with the way armed conflict is presented by its participants.

Ethics vs aesthetics

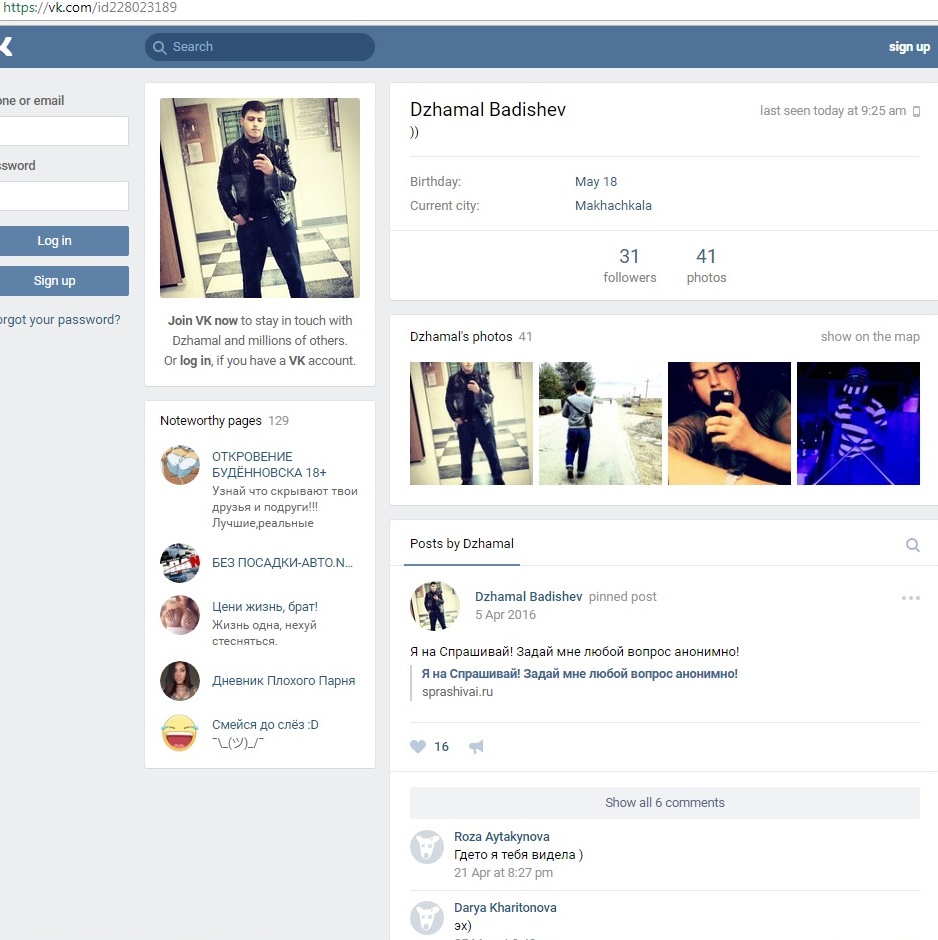

In 2014, as soon as armed conflict broke out in the Donbas region, a number of Ukrainian mass media established a rubric headed ‘evidence of Russian aggression against Ukraine’, where they reproduced public posts by Russian soldiers from Ukrainian territory. These might include photos posted on social media with a marked geolocation or containing certain characteristic visual elements. Photos from occupied territories continue to appear to this day, and are publicly accessible. They can be found by searching for a specific geographical address using geolocation tools; this kind of information is also often included in research reports by international groups.3 Thus photos and posts on social media in fact provide legal arguments that may disprove or corroborate specific information. This means that visual information published on social media becomes a judicial matter.

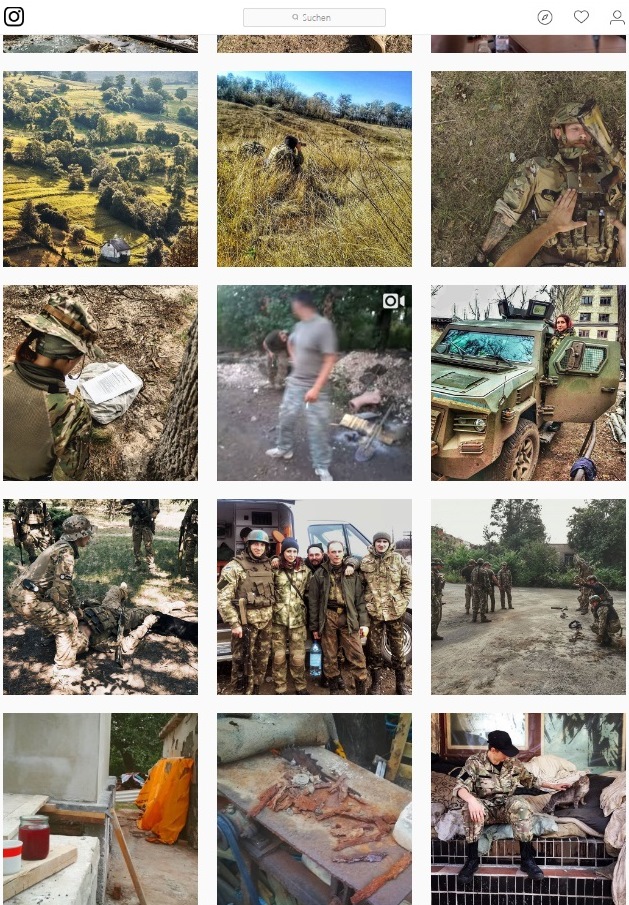

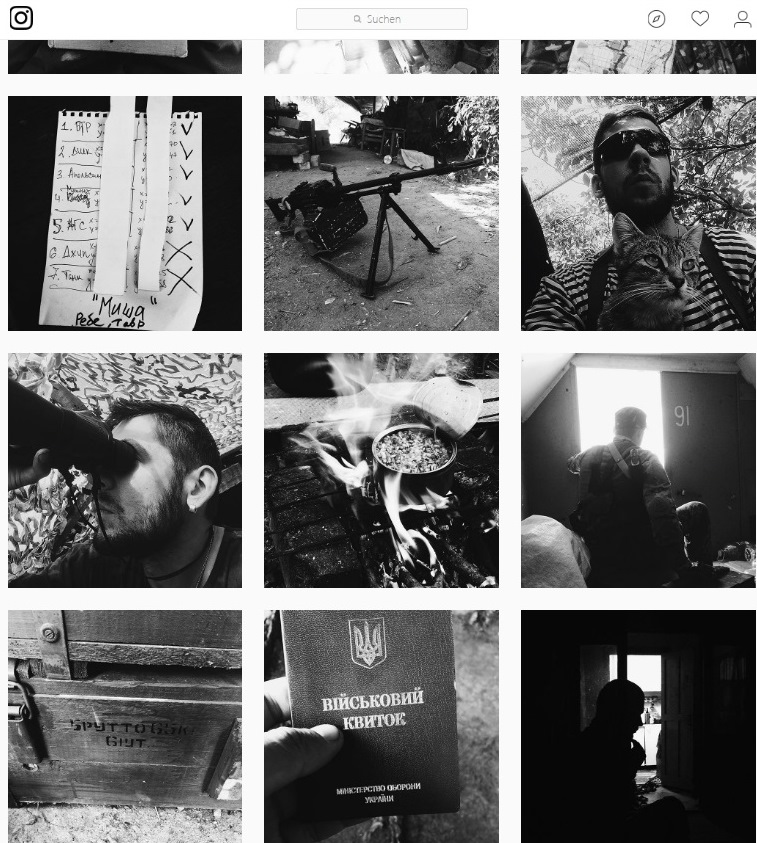

Photos: Dzhamal Badishev from Makhachkala (Russian Federation). Source: vk.com, Instagram

Art historians and photography researchers have frequently wondered how objective a photograph per se can be. Although the discussion on the subject continues, there is a consensus that every photograph is the result of manipulation on the part of the author who has chosen a certain angle, as well as on the part of the person who has disseminated it by posting it and placing it in a particular context. However, in terms of manipulation of photos on Instagram, it is worth pointing out that virtually every photo is processed by a filter, which is an integral part of this social network, as well as by photo-editing software, apps and services such as Hipstamatic, VSCO, Lazout, Hyperlapse, and others.

Meryl Alper, Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Northeastern University, discusses similar issues of deconstructing and constructing reality in the digital age in her 2013 article War on Instagram: Framing conflict photojournalism with mobile photography apps.4 She has examined the work of professional US photojournalists who have documented the experience of American soldiers in Afghanistan using Hipstamatic, a popular photo app. Alper raises the question of journalistic ethics: can such distorted pictures faithfully reflect reality? To what extent has the new media aesthetics been influenced by ideology?

One of the arguments put forward by photojournalists is their proximity to the soldiers. The photographer Damon Winter, author of the New York Times feature story ‘A Grunt’s Life’, said that Hipstamatic was the only app available to him at that time that enabled him to capture his photo story, bringing him as close as possible to the soldiers and capturing the actual situation. The photojournalist insisted that his snapshots did not ideologise or romanticise the war but, taken as they were in close proximity to the soldiers, are an honest reflection of the reality of the soldiers’ lives.

Alper notes that in the pursuit of ‘proximity’ to an event and its protagonists, images like these end up simulating a ‘soldier’s hand’ and a ‘soldier’s gaze’:

‘Hipstamatic photos of soldiers’ everyday lives, taken by professionals to look purposefully “amateurish”, are ethically questionable if we consider that these photos are taken by professionals to appear “as if” seen through a soldier’s eyes – or a soldier’s own iPhone.’5

While discussing contemporary photography – digital, instant or that processed by certain filters – in his study Of Symbolic Power and Big Data: Instagram & the Disruption of Media Photography in the 21st Century, Erik Palmer, Assistant Professor of Convergent Media at Southern Oregon University, explores which kind of photo is most powerful and influential at present: a picture captured by a professional reporter, or an instant snapshot taken by someone who, though an amateur, is a direct participant in the event?6 In other words, can photos on new media compete with the work of photographers of world renown?

How can we characterize an image in the new technical (digital) age?

To find an answer to this question I undertook to examine what kind of reality is being shaped and transmitted by the soldiers themselves, and how they appear to their audience and to themselves. To do so I chose Instagram as the subject of my examination, analysing published content marked with the geolocation positions Donetsk oblast and Luhansk oblast, and have focused on photos of Ukrainian soldiers as well as content published under the hashtag #warinukraine. In addition, I interviewed four Ukrainian soldiers, both conscripts and volunteers, who have completed their frontline service.

An examination of the content published under the hashtag #warinukraine shows that the soldiers’ posts are not the only ones appearing in this sequence. The 2611 photo posts (as of 11 October 2017) also include advertising content (the promotion of thematic merchandise such as T-shirts), information provided by military doctors, volunteers and journalists, as well as posts by individuals who were not directly involved in military action but were ordinary users (this kind of content is often of a heroic and patriotic nature: flags, Cossacks, and other symbolic images). I will, however, focus on the analysis of posts by soldiers, both conscripts and volunteers, who have completed their stint on the battlefront.

#warinukraine images. Source: Instagram

In the early days of the war young volunteers were often referred to as hipsters. On the other hand, it was pointed out that these young people drew their knowledge of the world from social media and the internet and were allegedly not fit for real life, while others emphasized the fact that they were young and emotional. I wonder if youth is really an angle unique to present-day circumstances – surely the soldiers fighting in Vietnam or in the Afghan war were also young?

Commentators have conceded that what drove young men and women to the front line following Euromaidan might have been a sense of duty but they sarcastically questioned whether these ‘hipsters’7 would be able to cope on the battlefield if they were forced to exchange their proverbial lattes in cosy cafés for cold tea in the middle of a forest or a field, in real war conditions.

It is worth pointing out that it is not only the sobriquet ‘hipster’ – quite broad and superficial in the Ukrainian context – that matters but rather the emphasis on the young age of the combatants and their way of life, in particular their desire to join in and be part of the conversation.

It also worth noting that social media are a standard feature on all smartphones, whose price in Ukraine ranges from 1,600 hryvnias (USD 60) to 20,000 hryvnias (USD 850) or more. One can therefore confidently claim that this kind of device is more or less accessible to the average Ukrainian. On the other hand, the fact that someone owns the technical means, be it a phone, tablet or computer, does not necessarily guarantee that they will be actively using social media. Activity on such platforms is often linked to a person’s lifestyle and their civic attitudes. Social media are undoubtedly a contemporary tool used by the new generation of people born predominantly from the 1980s onwards. Men and women with social media accounts are certainly young and active but we may query whether youth alone influences their understanding of war.

(Self-)representation of Ukrainian fighters on Instagram

Vitaly O., who holds a PhD in political science, was a war veteran by the age of 29. The young man was born in the town of Liman, Donetsk Region, and graduated from the History Department of Donetsk University. When the war broke out he volunteered to join the Artyomovsk Battalion, serving until 2015. The young veteran told me that almost nobody apart from himself in his battalion used Instagram, and that none of the officers was interested in, or ever checked, what the soldiers were posting on social media. Vitaly posted pictures of himself (including selfies), photos in camouflage, snapshots of his friends, as well as those of ordinary equipment and weapons. His photos were often accompanied by humorous captions. For example, the caption under the picture showing a soldier in a tank, with his head sticking out, read: ‘No, gentlemen, it’s not comfortable to sit in the tank for someone my size.’ Another example is the photo of a soldier sleeping on a pile of wood, captioned: ‘Very comfy’ followed by the comment: ‘By the way, [this is] the warmest place.’

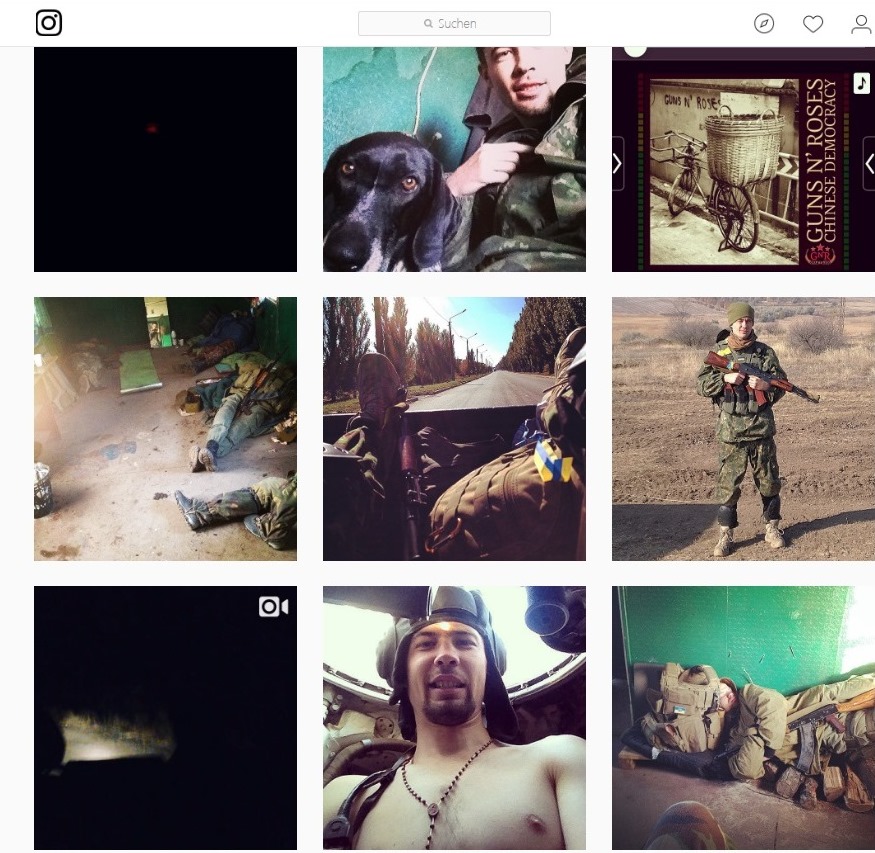

Vitaly O.’s Instagram images. Source: Instagram

Vitaly says that humour was one of the few things that helped the men on the battlefront to keep sane and in touch with reality. Another thing that gave them strength and support during the war were pictures of animals. Photos showing cats and dogs were a constant theme on Vitaly’s Instagram account. The young men said that they had come across lots of pets abandoned by their owners and that the combatants gave them a new home:

‘Cats and dogs in wartime are like an antidepressant. Whenever we saw an animal we couldn’t just leave it. We would take it with us or pass it on to members of our families.’

Since leaving the army, he has run Facebook and Twitter pages devoted to Ukrainian Army Cats and Dogs, where he periodically posts photos from the battlefront.

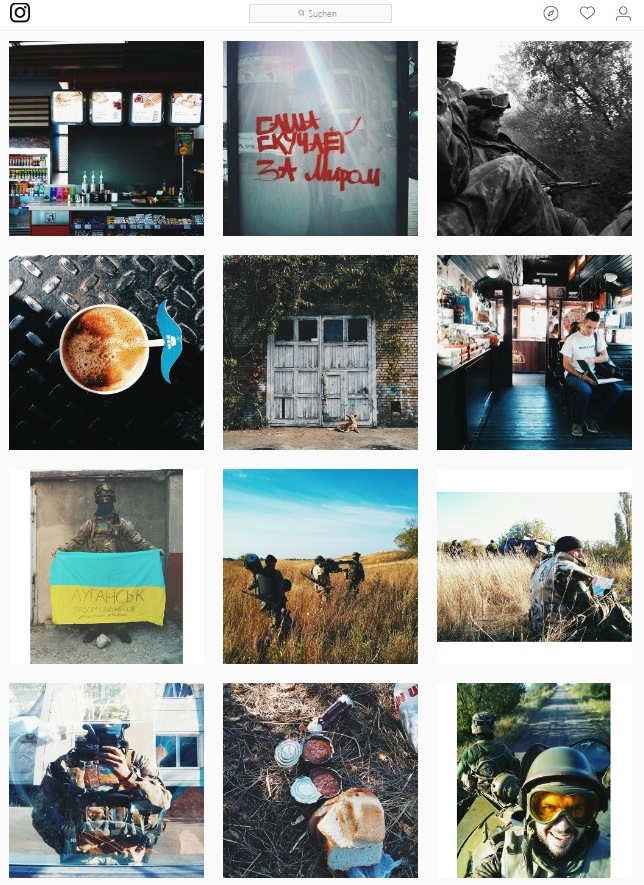

Unlike Vitaly, another volunteer, Dmytro, who served with the Aydar Battalion, posted very few photos during his service. He was also one of the few who used social media while serving but, as he himself points out, only when he had the time and when the internet was working. A law graduate, he had lived and worked in Luhansk for several years before the war and the Luhansk Region was also where he enlisted for service. He posted one of his first photos right after his first night there, which he said had been very difficult. The young man said that he initially had only a few followers but after he started posting photos from the war zone (mainly selfies) they immediately got lots of likes. Also, Dmytro’s content is full of irony, directed at the hipster culture in particular. For example, he posted a photo of a loaf of bread with tins of stewed meat. The caption read: ‘Morning meat smoothie’. When someone commented on the photos with the question ‘Where are you?’ he responded: ‘[At] a food festival in Luhansk region.’

Dmytro’s Instagram images. Source: Instagram

Instagram gave the young man an opportunity to share a different view of the army – not that of a state institution in a state of decline, incapable of functioning properly, but rather a place where young volunteer soldiers with higher education chose to serve, consciously joining the army to defend their country’s borders. When the war first began, many articles appeared in Ukrainian mass media describing the army’s state of decline, and the fact that the army had to rely on the help of volunteers. The Aydar Battalion where Dmytro served had been presented as the most brutal battalion, with many looters in its ranks. He admits that soldiers of every kind served in his battalion but points out that there were only a few bad apples among them. His fellow fighters included four law graduates, an economist, as well as students of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. ‘We didn’t drink alcohol, which is why we were in the good books of the top brass,’ the young man told me. After leaving the army he went to work for the Luhansk regional authority, and is currently volunteering in the village of Trekhizbenka in the Novoaydar district of the Luhansk Region.

While talking to Dmytro I raised the issue of military veterans, people of varying ages who, after finishing their service, have faced the question of what to do next. For Ukraine, a country that had not previously been involved in a war, the issue of reintegrating young veterans is new and quite critical. In the absence of a state policy, the issue is dealt with by various individual social and private initiatives and through popularising the image of ‘the self-made man’. Ukrainian media love success stories, such as those featuring a 21-year-old war veteran who has opened a café, or one who has been baking pastry for general sale. However, another important issue is often lost amidst these optimistic stories: that of badly needed psychological and social care and rehabilitation of invalids to help them overcome social isolation, and also the reintegration of young invalids.

The story of the veteran Roman N., an army conscript who started his own street-food business after the war, is very similar to those beloved of the Ukrainian media. What distinguishes the war photographs on his profile is the fact that over 90 per cent of his shots were processed by a black-and-white filter. This relates especially to photos taken in the period 17 August 2015 to 15 October 2016, when he saw service on the battlefront. One of his photos, showing houses that had been destroyed and a landscape strewn with wreckage, may not be of the highest aesthetic quality. However, the caption under the photo, ‘Museum of the war in Ukraine’, imbues the image with special meaning. ‘In a war everything is clear, you know what’s black and what’s white. That is precisely why I chose this particular filter when posting photos from the battlefront. In my present everyday life I try not to post black-and-white photos because in everyday life nothing is clear, everything is unstable, and everything is ambiguous,’ the young man told me.

Roman N.’s Instagram images. Source: Instagram

The veteran told me that after he used this technique, several of his soldier friends followed his example and retouched the military reality, converting it into black-and-white images. The young man said that the content posted by his soldier friends varies and that social networks (Instagram as well as Facebook) often help the soldiers to appeal to the public for help in, for example, collecting funds for weapons and military equipment, or to pay for prosthetics.

The Ukrainian soldiers I talked to said that, even though they had encountered no official prohibitions regarding content, they had never posted photos that showed strategic facilities or that would reveal military deployments. In addition, they would always check with their friends if they could post their photos on social media, and if the answer was no, they would blank their faces or refrain from posting the images altogether. This type of ‘media hygiene’ or awareness of ethical issues often results from the fact that the young soldiers understand how information works and how inflammatory it can become if it falls into the hands of propaganda.

Roman K. said that from time to time during his military service on the front lines the officers would try to ban the use of social media. However, this was probably because of their apprehension about, and lack of familiarity with, what the soldiers tended to post. Roman K. himself says that he rarely used social media on the battlefront and did not take many pictures, and now regrets that much of his experience on the front was not captured and could not be added to his personal archive: ‘When things got really scary, we simply didn’t have the time to think, let alone take pictures. Now I’m sorry that much of this hasn’t been captured, especially my friends.’

Regardless of their varied war experiences, the varying content posted and its frequency and quality, all the young men I interviewed said that during their time on the battlefront Instagram allowed them to keep in touch with the world, to receive news from their friends and family. It provided them with outside support and enabled them to let their relatives know that they were all right.

‘For me this social network was a connection with the outside world. I was able to see what my friends were doing and I pretended that I was fine, too. I told my life story,’ says Vitaly O.

For many of the soldiers what mattered more than posting their own content was being able to see photos showing a peaceful life, images from which they could draw strength when in battle.

In terms of the content the young men shared while serving in the army, it is worth noting that it is completely free of open aggression, hatred or heroism. Ironic content often went hand in hand with courage, although this courage never amounted to creating a heroic image of the soldier in the way promoted, for example, by US media. On the one hand, US media present the image of ‘sexy warriors’, who are robotic, strong, tough, handsome and desired by women; on the other, they publish inspiring stories of veterans who, while in action, have come to terms with their pain and continue to demonstrate their will to live, despite injuries and amputations. In Ukraine the narrative of the strong and tough, virtually invincible, hero has been created in relation to the defenders of Donetsk airport. Following a throwaway comment by a DNR fighter describing the situation at the airport, Ukrainian soldiers became known as ‘cyborgs’.8

However, this kind of heroic attitude to war is absent from the comments on the soldiers’ own personal photos. In this respect, the soldiers have turned the social network Instagram into a voice that humanises the war, the voice of a soldier capable of love and compassion and of surviving hardship. For example, along with content relating to the war, Roman N. posted photos of his sweetheart, whom he married after the war.

The soldiers I interviewed have all said that what mattered to them was posting photos as the events unfolded, creating their story while living it at the same time. Dmytro told me that he had never posted photos post factum, once they started getting lost in his phone’s personal archive. Roman N. was also quick to share his photos even though many of them were quite abstract, showing a landscape or details of ‘soldier interiors’. These men believe that what gives these snapshots their ‘aura’9 is their own experience of the events and their personal memories, shaped in the course of documenting them.

A photograph or an illustration?

The difference between photos taken by photojournalists whose work was examined by Meryl Alper and those taken by soldiers themselves consists in the fact that while photos taken by the former serve to illustrate a text, for the latter the photo is an imprint of personal memory and emotional state. Thus, one of Dmytro’s first photos was taken after his first night at the battlefront. Riding in a car after a difficult night he posted his ‘happy face’, which does not directly speak of his experience but captures his wish to survive.

In her analysis of war correspondents’ photos taken during military conflicts Susan Sontag says that these pictures are meant to arouse the strongest possible emotions in the viewer – fear, compassion, pain. At the same time, Sontag says that by disseminating images of cruelty and violence, the media only lower the threshold of real pain and, consequently, the extent of compassion. Thousands of identical pictures capturing the events in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq or Vietnam do not illustrate a specific event but a specific emotional component – pain, despair, courage, fighting, victory, death, and so forth.

During the four years I spent working in Ukrainian media and examining the subject of war photography, I noticed that the media in Ukraine have used photographs as illustrations more often than treating them as separate stories. Every day might bring several items of news from the war, with the media trying to illustrate each with photographs in the hope that the photos will make the readers click on the link and read the news item in full. But where to find so many unique photographs? Undoubtedly, Ukrainian newsrooms often dispatch their own photojournalists to the battlefront to find their own stories and capture their own snapshots. However, many will buy photographs from photo banks and various news and photo agencies. Thus the same photo might be published and republished by various media several times a week. Another matter are photos from social networks, which are ‘resurrected’ (apparently as part of political spin and manipulation) by the media: what I have in mind are the innumerable photos published in the context of the war in the Donbas which, however, originate from Chechnya, Afghanistan and Syria. All media are duty-bound to do fact-checking and double check every news item as well as every photograph. Nevertheless, the fact that such fakes do exist suggests that the media are paying less attention to images, and that they regard photos merely as illustrative material corroborating or refuting a particular news story.

Those studying social networks claim that the new media erase what is unique, since all social media users use the same visual clichés and the same filters, and virtually everyone uses the same visual language. As a result, the casual reader no longer sees a soldier’s personal story, which is pushed into the background, and instead views the pictures as abstract images of ruined landscapes or everyday military life.

On the other hand, personal ‘diary’ photos can be the subject of further study. A more detailed examination of profiles, comments, photo captions, etc., can nevertheless enable us to trace the individual uniqueness that is alleged to be lost on social networks. Stories like these humanise the war by showing the faces and life stories of individual soldiers.

However, is it possible for the emotional component of social media to counter the narrative of war and wartime heroism? How much emotional involvement is a soldier or combatant capable of while participating in military action? Is he supposed to show his limitless strength or does he have sufficient human courage to keep up his own military spirit? Is a person like this capable of showing his own weakness and, if so, what exactly constitutes this weakness?

In many respects, the soldiers who publish photos during the war are trying out several roles at the same time – that of a participant in events, of a witness, and of a mediator who transmits information to the outside world. The question remains how to ensure that the voice of the eyewitness, as well as that of the participant and mediator, is heard properly.

Levinson, Paul. New New Media (2009/2012) Penguin/Pearson, revised edition (2012) and Levinson, Paul. Digital McLuhan: A Guide to the Information Millennium. N.Y., Routledge, 1999. p. 240.

Manovich, Lev. Instagram and Contemporary Image. 2017. See: http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/instagram-and-contemporary-image (retrieved 20.09.2017).

Hiding in Plain Sight: Putin's War in Ukraine, by Maksymilian Czuperski, John Herbst, Eliot Higgins, Alina Polyakova, and Damon Wilson. AtlanticCouncil.org, 15 October 2015. See: http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/hiding-in-plain-sight-putin-s-war-in-ukraine-and-boris-nemtsov-s-putin-war.

Alper, Meryl. ‘War on Instagram: Framing conflict photojournalism with mobile photography apps.’ New Media & Society, Volume 16, (published online: September 18, 2013; in print: December 1, 2014). See: https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813504265 (retrieved 20 October 2017).

Ibid.

Palmer, Erik. Of Symbolic Power and Big Data: Instagram & the Disruption of Media Photography in the 21st Century. See: http://bit.ly/2gyel5j (retrieved 20 October 2017).

Sergeyev, Sergei. Donetsk airport is defended by cyborgs! (Донецкий аэропорт защищают киборги!) [Electronic source]. Sergei Sergeyev. Obozrevatel’, 2014. See: http://bit.ly/2xDa2xn (retrieved 29 September 2017).

Cf. Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1968). In: Hannah Arendt, ed., Walter Benjamin, Illuminations. New York. pp. 217-252. §

Published 18 January 2018

Original in Russian

Translated by

Julia Sherwood

First published by Eurozine

© Kateryna Iakovlenko / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?