Voltaire gave French the instrument of polemics, he created the improvised, rapid, concise language of journalism.

A. de Lamartine

In the universal history of letters, there appear from time to time the creators of a new literary style, champions of a new taste or a different form of poetics, who go on to gain numerous followers and even subsequent cultivators of their ideas, whose work then surpasses that of the initial instigator. In the history of philosophical or scientific thought, there are several cases of creators of systems and a few architects of theories of genius in whose trail one can see clustered together a varicoloured string of disciples, standing in line in a more or less orderly fashion at the bus stop marked out by the master. However, it is far more unusual for someone to invent a new type of man of letters, a new trade within the field of those who study, think, write and speak. Thus, for example, credit for inventing the classical philosopher is commonly parcelled out between Thales, Heraclitus and Pythagoras; perhaps Baudelaire took out the patent on a certain kind of extravagant, doomed, Bohemian poet; and it was Freud who successfully instituted the psychoanalyst as the confessor of modernity, etcetera.

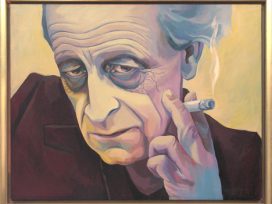

Portrait of Voltaire from the workshop of Nicolas de Largillière (1656-1746), created after 1724, 80 × 65 cm. Carnavalet Museum. Source: Wikimedia

Voltaire’s masterwork was the invention of the modern intellectual, a profession that incorporates something of the political agitator, quite a bit of the prophet and not a little of a spiritual director. This suspicious but venerated creature reached the peak of its prestige exactly a hundred years ago, with the Dreyfus Affair and Émile Zola’s J’Accuse; it then maintained its pre-eminence for three-quarters of the twentieth century, sustained by such figures as Romain Rolland, Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre, only to fall into a state of decadence in the last twenty years. This decline could be terminal, or perhaps the intellectual will experience a metamorphosis with the aid of qualitative advances in communications media and the new possibilities that have opened up as a result. After all, the development of the press, the extension of the postal service and investments made by private capital in publishing enterprises during the eighteenth century played no small part in Voltaire’s invention. It is logical to expect that the new information highways will foster the appearance of the intellectual’s successor; we are still awaiting a Voltaire among bloggers, with a Facebook and Twitter account… However, be that as it may, it is beyond doubt that the figure of the intellectual as we have known it has been of crucial importance to forging the best and the worst of our contemporary cultural identity.

Voltaire was not the great tragedian that he himself dreamt of being and some of his contemporaries believed him to be, and still less an outstanding poet. Those of his essays that can properly be called philosophical skilfully publicized some of the ideas of Locke and Spinoza, as filtered through Bayle, but are neither very original nor very profound. As a historian he put forward new and advanced criteria, similar to those of Hume but in some instances anticipating him, and deployed an erudition that was exceptionally comprehensive for the time; nevertheless, it is frankly improbable that his achievements in this field alone would have guaranteed him the outstanding position he occupies in the intellectual revolution of his century. Although some of his fictional works are immaculate, such as Candide, Zadig or Micromégas, they did not transform the genre or attain the profound originality of Gulliver’s Travels (from which Voltaire drew so much inspiration), Sterne’s Tristram Shandy or Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew. As for his sociological or political analyses, although they are full of sensible observations, in their power of suggestion they do not match the radical provocation of Rousseau at his best, or even of Helvétius. One could say of Voltaire what Jean d’Ormesson observed upon the death of Jean-Paul Sartre: “Rather than one definitive masterwork, he has left us multiple demonstrations of an immense talent.”

What then really remains of Voltaire? The example of his militancy, what we could define as his intellectual vocation to intervene. Descartes, and later Spinoza, wrote in order to correct and amend the dominant intellective methods of their time; Voltaire accepted and radicalized this process of correction, but also extended it not just to the way in which we understand but also to what was understood. In contrast to the first rationalists, Voltaire did not simply seek to modify our understanding of the world, or the individual conduct of the wise man in the world, but wished to alter the world itself. The famous thesis of Marx, according to which it is necessary to move on from interpreting the world to transforming it, has an explicit and admirably spirited precedent in Voltaire. No one before him realized with such clarity the regenerative force that ideas could exert on the obscure and custom-bound structure of society. In knowledge and properly oriented thought (which, when combined, Voltaire called “philosophy”), there lay a genuine power, a beneficent and healing power that offered relief from the despotic power of rulers and the obscurantist power of the clergy. However, this philosophical power had to be mobilized, it had to be taken out of academic books and into the street, and converted into a battering ram and a banner. For this to happen a series of conditions were necessary, which before Voltaire no one had consciously conceived of as a whole: a particular historical vision, a rational faith, a particular discipline, an instrument of propaganda and polemic, and a receptive public. Let us examine in greater detail how each of these requirements played its part in Voltaire’s dynamic outlook.

a) Historical vision

Montesquieu clearly perceived the diversity of political customs across time and across different latitudes, but accepted that all of them had their justification and reasons for existing. This applied even in the case of the most apparently nonsensical or atrocious laws, all of which could be justified when closely examined, related to environmental conditions or the character of the human group in question. There are many different ways of adapting to the limits of what is rational, and the fact that we prefer one or the other depends upon our traditions, that is, our prejudices. And vice versa: every society cultivates its own absurdities and particular examples of ridiculousness and inconsistency. Perhaps the system of the Parisians has advantages over that of the Persians, but naturally not enough to oblige all Persians to behave like Parisians. In opposition to this vision of serenely functionalist optimism stood the radical scepticism of the great pessimists like Pascal or Bayle. For Montesquieu, reason was everywhere; for the pessimists, all human reason is madness and only an irrational commitment to faith can save us. That is, save us from the world, because nothing can save the world. Behind human strivings, there is nothing more than gross ambition, frivolity, intentions that are criminal in the worst of cases and stupid in the best. While for Montesquieu everything was ultimately justifiable, for Pascal and Bayle nothing was, save for the act of faith that annuls our proclivity to desire earthly rewards.

Anyone who does not feel any indignation in the face of political absurdities past and present cannot feel any revolutionary impulse; neither can those who consider these absurdities illustrative of a metaphysical affliction that human efforts can do nothing to remedy and can only make worse. In contrast to which, Voltaire’s vision of history combined the same ingredients in different proportions. In his view, abuses and absurdities of law were not merely thoughtless phenomena, as Montesquieu had believed, but very real evils.

However, equally, they did not exemplify the sad condition of fallen man but stemmed from intelligible and alterable causes: the abusive self-interest of the powerful and the ignorance of the masses, fomented by the inventors of superstitions. Our rational nature and innate sense of justice rebel against the brutalities of the past, the scars of which are only too visible in the present. There are no reasons for optimism, naturally; to imply that there were would represent a lack of honesty in the face of the gallery of horrors that is human history, the tragedy repeated all over the world only with different leading actors. However, neither is resignation decent or acceptable, given the efforts of so many honourable men who have opposed tyrants, of so many learned men who have fought ignorance and superstition, and of those rulers who have made intervals of relative well-being possible in the midst of much more frequent episodes of barbarism. All of these demonstrate that it is possible to make a positive intervention in the bleak course of destiny, in order gradually to cleanse it of its worst tendencies.

b) Rational faith

Rivarol was mistaken when he said that Voltaire’s thought was mocking, corrosive, conducive to destruction and nothing more, lacking “anything that could give it cohesion or systematize it”. Very much on the contrary, Voltaire was a believer, and there is in his philosophy a foundation that is as clearly defined and stable as any religious dogma. Voltaire believed in a natural law, which he did not vacillate in granting divine origin, and the undoubtable expression of which could be found in the reason and the hearts of men. What he denounced in superstition was its permanent variability, the unending range of its metamorphoses in accordance with various chronologies and geographical coordinates.

Natural law in contrast was singular and undivided, its universality applied everywhere and at all times, thus confirming the unquestionable rectitude of its demands. Just as every child in every country takes a run-up before jumping, without needing someone to teach them physics first; and just as anyone in search of a hiding place might position himself so that a tree stands between him and his pursuers without first having to study perspective, so too there is in every man an idea of the just and the unjust that is common to all, independently of and prior to any specific legislation, and by which we may all be judged at the same time. It could take centuries to discover the laws of physical nature, but simple introspection permits an honest man to recognize in just one moment the eternal laws of morality.

Voltairian faith is a passionate affirmation of reason, which in his doctrine occupies the role played by sanctifying grace in Christianity. In effect, reason is the grace that God grants us to compensate for the many ills of life, the only positive exception made in our favour in the inexorable laws of nature. This is why Voltaire was just as intellectually severe with atheists as he was with the conspicuously pious; both groups failed to recognize the true rational greatness of God. Reason, together with a self-love that seeks the best for each individual and a benevolence that leads us to desire whatever is most beneficial for our fellow beings, creates an underlying framework that both sustains man’s social life and requires its permanent re-examination, its constant improvement. As already indicated, in spite of Voltaire’s superficial fame as a sarcastic, calculating figure, his affirmation of the foundations necessary for social life and its perfectibility is not at all cold, but a real passion.

It was very well described by Bernard Groethuysen, in his Philosophie de la Révolution Française, as a “passion that demands the destruction of the irrational, of the absurd, and which seeks to put into effect in life whatever is in accordance with reason and a sense of what is right. A passion for reason that sees the foundation and the goal of reason to be whatever is conceived in accordance with the logic of what is right, a passion that suffers, objectively and impersonally, at the sight of all the practical situations in everyday life that run contrary to reason. Ultimately, a passion so sensitive to injustice that it could not fail to intervene in specific incidents, following the general laws of a reason that was clear and sure of itself, wherever they might occur.”

c) Discipline

Voltaire is one of those figures in the history of thought to whom one can attribute the fewest odd ideas. To a certain extent this is something that has been turned against him: we tend to remember thinkers above all for their most outrageous dictums, their most brilliantly extravagant or paradoxical precepts. The principal ideas of Voltaire, in contrast, now form part of the shared body of our modern common sense, so that when we read him his ideas can sometimes seem too obvious, too predictable. The majority of his viewpoints have succeeded to such an extent that we now consider them irrefutably ours, and look down on him a little for not having put forward others that might have disconcerted us more. However, the fact is that Voltaire always saw very clearly where he wished his opinions to lead, for no writer was less capricious or less casual in their statements.

Compare him with the tirelessly imaginative Diderot: the editor of the Encyclopédie always sought to think of things in a way that was different to established practice, but without concerning himself with the practical consequences of his audacious and sometimes contradictory speculations. Diderot threw himself into pursuing a shocking idea to its most extreme, defying conventions but without making any decided effort to transform them, and more out of a taste for free speculation than for any practical purpose. He was not even concerned about making public several of his most original philosophical works, which where not published until many years after his death (as was the case both with Rameau’s Nephew, which Goethe rescued and first published in German early in the nineteenth century, and with D’Alembert’s Dream).

Voltaire however never lost sight of the social purpose of the lessons he gave. He was never gratuitous in his propositions, but always set out to combat some sort of error or to arouse the intellectual attitude that seemed most historically productive in each case. He knew how to be entertaining at almost every turn, but always for tactical reasons, to interest and retain the attention of his readers, never out of simple frivolity. He was a great pedagogue and an excellent publicist, much more so than a practitioner of creative speculation. But he was also a man committed to a specific party (and a persecuted party too, as he made clear in some of his letters), a committed militant. His party was that of the philosophers, whom he wished to convert into intellectual guerrillas. He despaired at their disunity, at their feuds and personal jealousies, and the internal clashes that weakened them in the face of the cohesive mass of fanatics and the intolerant. Using the faithful Damilaville and more lukewarm D’Alembert as intermediaries, he sent them furious harangues in an epic-burlesque tone, full of appeals to the fraternal unity of the group and tactical and strategic suggestions for achieving victory in the war against obscurantism. His support for the Encyclopédie was not so much due to a commitment to the work itself – he had substantial reservations regarding its intellectual orientation, and though he was prolific when it came to collaborating in writing articles, those for which he was responsible lacked enthusiasm. Rather, he desired a shared project that would bring the otherwise scattered authors together and instil discipline in them, in opposition to the common adversary. The way in which he applied this collectively oriented, bellicose attitude to the secular terrain was no doubt inspired by the legacy of the members of the Society of Jesus who had been his first masters. Perhaps we should say that the invention of the modern intellectual – polemical, worldly, opportunist in details but faithful to his principles, and above all an educator – was attributable in equal measure to both Ignatius of Loyola and Voltaire…

d) An instrument of combat

The Voltairian style is without any doubt one of the most potent weapons ever to have been deployed in the civilized arena. It is easy to eulogize it, but more complicated to analyse all of its mechanisms. One of its many enthusiastic admirers was Somerset Maugham, who asserted in The Summing Up that Voltaire was “the best writer of prose that our modern world has seen”. For Maugham, writing good prose required good manners; in contrast to poetry, prose is a civil, even courtly matter. The subtlety and malicious restraint of Voltaire tarnished his verse but allowed him to achieve a prose style that has proved itself enviably impermeable to the passing of centuries and to shifts in literary fashion. He knew how to combine classicism with a certain occasional carelessness, to which he added the self-assurance of spontaneity, all in a manner admirably suited to his peculiar sense of humour. He was polite but aggressive; clear and direct but rich in double meanings; polished and even punctilious at times in his respect for form, but incomparably vivacious. Above all he possessed two magisterial qualities: clarity and brevity. He is easily comprehensible, gets to the heart of the matter, he avoids circumlocutions, he consistently resorts to illustrative images that persuade by making us smile and doesn’t waste the time of a reader whom he correctly assumes to be in a hurry and a little distracted. He knows his modern man… Nor does he entangle himself in long and complicated arguments, and is even distrustful of them; he demonstrates the absurdity of his adversaries in a couple of brief strokes, he contrasts opposing extremes with imaginary dialogues, he never explicitly expounds the correct route forward but enables it to appear in the mind of the reader. He is content to demolish stupidity and give a gentle shake to the faculty of rationality we all share in order to awaken it: come on, now it’s your turn, don’t be frightened… A true model, which Somerset Maugham made into advice for young writers, saying “If you could write lucidly, simply, euphoniously and yet with liveliness you would write perfectly; you would write like Voltaire”.

One has to insist that Voltaire was without doubt a doctrinaire writer, but not a hypnotizer of the masses or a trickster. He did not vociferously expound dogmas but preferred to undermine the foundations of existing ones with humour, and as to the correct point of view, he hoped that everyone would arrive at it by themselves. This was not a matter, nor anything like it, of considering all opinions to be of equivalent value, or imagining that the inspirations of anyone and everyone should be respected to the same extent that one should respect the persons to whom they occur. These contemporary deviations of relativism are something to which Voltaire, fortunately, did not even come close. Voltaire believed that we would all think well (and therefore more or less in the same way) if we were allowed to; that is to say, if we were not taught or obliged to think badly. He wrote against the obstacles to truth, trusting that the latter would then be able to make its own way forward on the basis of the reason and natural law that we all share. Hence his fame for being “destructive”, an attribute that he himself confirmed. However, it was precisely through this method that, as Groethuysen accurately pointed out in the study mentioned earlier, Voltaire “appealed to the autonomy of thought of each individual”. His motto could therefore have been, “Trust in your own reasoning, always substitute concrete, definite observations for indecisive or generalized assertions”. Vagueness and the deceptions of imprecision are the great enemies of rational effort. One therefore has to be clear when one writes, for the sake of honesty and remaining true to one’s own principles. Writing clearly is not by any means the same as having everything clearly worked out in advance. In the kingdom of superstitions and false science, doubt is a demonstration of cautious good sense. This is why Voltaire liked to present his writings as dialogues between opposing positions, full of unforeseen rapprochements between apparently irreconcilable attitudes and bottomless divisions between others that had previously seemed the closest together. He thus put forward materials for his readers to reflect upon, without attempting thereby to take the place of reflection. The process through which we approach the truth is an infinite task, and it is necessary to retain our good sense so that we might recognize that many of the questions we ask ourselves will always lack an answer that settles them definitively and forever. God has given us reason in order to comprehend the things that concern us, but not to understand everything in the infinite and eternal universe. Reason should therefore be daring (and thus free itself from tutelages and traditions that have been accepted without any criticism), but also modest, so that we acknowledge our limits. The favourite trick of religious and political necromancers is precisely to promise knowledge that speaks of the absolute with insulting or unquestioning familiarity. It was against the same necromancers that Voltaire fired his arrows, clearly and concisely. His objective was to make each individual conscious of their intellectual independence.

e) A public

For an undertaking such as his to have any prospect of success, Voltaire needed to create a public for himself. This he achieved, and on a scale much larger than anyone could have expected. Many sectors of society had to be discounted in advance as potential fields of influence; to begin with, the clergy and most of all the ecclesiastical dignitaries, the overtly pious, the traffickers in papal influence, the preachers, confessors, inquisitors… Equally, too, the heretics such as the Jansenists or infidels on the Muslim model, who suffered under the intolerance of their adversaries and yet had no fonder dream than to exercise the same power themselves, only even more severely. Nor could Voltaire count on figures in the upper echelons of the universities, guardians of orthodoxies by temperament and habit, or the most hardened offshoots of the old feudal nobility, who could only hope to continue enjoying their privileges by permanently freezing the hierarchies of this world. The common people, of course, remained completely out of the question as an ideal audience. Its members lacked intellectual concerns and personal independence, both qualities necessarily linked to a certain level of economic well-being. In contrast to other more revolutionary Enlightenment figures such as Helvétius and later Condorcet, Voltaire was never a supporter of extending education to the social strata who had to work in heavy manual labour. After all, what would have been the point of increasing their knowledge, if they could never abandon their brutalizing yet indispensable service, thus rendering this knowledge of no use to them whatsoever? It was enough to give the people a few norms of healthy morality, and then some entertainment to alleviate their burdens from time to time. Abstruse philosophical deliberations, let alone those of a theological variety, when preached to people who could neither understand them nor had any need to do so, but were nevertheless still excited by them, could give rise to bloody disputes, outbursts of persecution and religious wars.

Who then was left to make up this public, from which Voltaire hoped to obtain all his strength, a strength capable of rationally regenerating the structure of society and even the whole of civilized humanity? Decent people: professionals (above all doctors and young teachers), financiers, merchants, artisans, public officials, military men with a will to study, scientists from any of the academies, artists, travellers, libertine Abbés, ladies who were as sensitive as they were welleducated and culturally restless, members of the lesser and even in some exceptional cases the higher nobility (the Duke of Alba and the Count of Aranda were two examples in Spain, both regarded by Voltaire with the utmost appreciation). As two rarities, we can also add a king, Frederick of Prussia, and an empress, Catherine of Russia. People with curiosity, with a certain amount of leisure, with education and without too many prejudices. The cultured, moderate bourgeoisie, enemies of war and friends to business, and passionately excited by the new scientific discoveries and new economic abundance. Voltaire knew that this enlightened public could never form a majority. Instead, it constituted the most active and influential section of society. Winning them over to the side of philosophical ideas would be enough to transform the whole of society. This public, tolerant and well-informed, would also constitute the collective legislator that Voltaire wished to see in action, in opposition to genealogical privileges and superstitious traditions.

For Voltairian pragmatism, the important point was that laws should be made by those best equipped to formulate them; in this he differed completely from the position that would be put forward a few decades later by the revolutionaries, who demanded that the law should be decided not by those with most aptitude but by all those with the right to legislate. Since no one should be obliged to submit to laws, the elaboration of which they themselves or their representatives have not taken part in… But that is another question. Voltaire, who was scarcely an egalitarian, if at all, wrote for a broad but select minority, not for a revolutionary majority. He himself was a rebel and a radical reformer, but he detested (and feared) the idea of a generalized violent insurrection.

Such were the readers of Voltaire across the whole of Europe. They waited expectantly for his pamphlets – unsigned, but written in a style that made them unmistakable – to receive slogans, stimulus, arguments against obscurantism. Although many of them were subscribers to the Encyclopédie, Voltaire prepared a Dictionnaire Philosophique for his followers, which was both piercing and portable; he knew that the secret of being effective lay in being not only entertaining but also accessible. When turned into a weapon of combat, the book had to become cheaper, lighter, smaller, easy to carry… and to conceal. At the same time, the use of alphabetical order enabled one to swiftly locate the ammunition required in combat with the reactionary enemy. Voltaire was, if not exactly the inventor of the pocket-sized, paperback book, at least one of the first to comprehend the multiple possibilities it created for the dissemination of critical ideas. The curious point here is that Voltaire was so successful in forging a public for himself that at times his audience turned against his own side. For the truth is that there were many more “Voltairians” than believers in the Enlightenment, and many of the worst enemies of the philosophes learnt their dialectical ploys from Voltaire himself. Take for example the case of Rivarol: who could be more Voltairian in his elegant precision and sarcasm, and yet more anti-Voltairian in terms of his underlying ideas? Voltaire fascinated even his adversaries, the most intelligent of which learnt from him in order to fight against him.

In the two centuries since his physical disappearance (a complete disappearance, since we have even lost track of his remains) his name has continued to retain its prestige as a recruiting flag for the cause of irreverence, but this has not spared him from reproach and censure. “An author who says perfectly what everyone thinks”, says one lady candidly, forgetting that in a good part of the world people think things because he said them first; “philosophy for hall porters”, decree those who only believe in the philosophy of fat volumes and intimidatory jargon. Madame de Staël, with greater critical judgement, pointed out that “this clarity, this facility that characterizes his works, enables him to see everything and yet not foresee anything”. In general, it is easier to disdain Voltaire than directly refute him; after all, his principal ideological obsessions are today almost commonplace ideas, and most of them form part of the spinal column that sustains our liberties and the best social aspirations of the modern era. Nevertheless, he continues to be as irritating as ever, though for changing reasons. Carlos Pujol, in his superb book on Voltaire, expressed this in a manner that cannot be bettered. “Overall”, he wrote, “he is an embarrassing author, whom it is not easy to attack head-on without lowering oneself almost to the level of a blockhead, but who at the same time is no more easy to accept en bloc, not even in terms of his main ideas, because he always contradicts something that we are not prepared to give up. For agnostics and atheists he is too timid, too wedded to a set of principles that can seem vague, but for him were solid; for religious believers, even those who come armed with all the post-conciliar goodwill they can manage to gather together, he evidently goes too far in his rationalism; for Marxists he is too bourgeois, too conservative, while for the bourgeois he has a critical acidity, very characteristic of the militant bourgeoisie of the eighteenth century, that today can appear intolerable; for sceptics he is too credulous and for those in possession of certainties, whichever they may be, he is too corrosive. Everyone looks at him askance, and does everything possible to leave him in an area of the past from which no one will reclaim him”.

Everyone? Perhaps less so today than twenty years ago, when Pujol wrote these lines. We are living through the punishing hangover of the breakdown of many millenarian or absolutist certainties; we now fear the resurgence of past atrocities in a more sophisticated form, the asphyxia of an intransigence that does not tolerate even the mere outline of a free rational examination that might contradict it. Above all, we fear that certain essential values of modernity might be forgotten, due to laziness or “multiculturalist” relativism. These are values that have always been a source of promise for the future of civilization and their hurried dismissal does not open a way to the future but only to barbarism. And we also fear the growing lack of interest in things that affect us all, in essential matters, in any far-reaching debate on what is happening today with a view to the effect it will have on tomorrow. Nobody wants to be bored, fine; but Voltaire teaches us how to entertain without being distracted from what is most important. His thought was simultaneously firm and pragmatic, passionate and rational; he did not accept any set of ideas all at once en bloc, but picked them over one by one, constructing a framework of difficult compatibilities in which no current of ideas was entirely excluded or admitted without examination. This progressive eclecticism is in large part similar to the pattern that many are trying to establish today, whether they are called “postmodern”, “neo-Enlightenment” or anything else. Heirs to the old humanism, naturally, who are berated by the absolutists on all sides in the same way that absolutists always berated Voltaire. Today, it would be absurd and misleading to revert crudely to a body of thought that sought constantly to remain wedded to its historical context. But, that tone, that vocation, that intellectual character… Yes, certainly, more than ever, we still need Voltaire.