Viktor Orbán’s war on the media

Since his return to power in 2010, Viktor Orbán has meticulously unravelled the rule of law and media pluralism, while holding the EU at bay. A short history of a decade’s attacks on the free press in Hungary.

A good part of the international audience only became familiar with the ongoing anti-democratic project in Hungary when the political upheaval of Brexit and Donald Trump’s election broke a narrative barrier: the shift of conservative politics toward the far-right hadn’t really been taken seriously until then. However, Hungarian PM Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz foray started as early as 2010, when the party won supermajority on the ruins of the 2008 financial crisis and the ashes of the formerly governing Socialist Party which had collapsed on itself multiple times in the preceding years.

Orbán had openly talked about preparing for 20 years of governing, and his government set out to make good on that promise. In unilaterally sacking the constitution to replace it with a Basic Law, they got rid of established institutions that should have served as checks and balances. An election reform has ensured their towering advantage despite only securing a maximum of 40 percent of the votes. A new media law instated an authority directly appointed and controlled by the government, paving the way for Fidesz’s overwhelming dominance of the media sphere. And the National Media and Communications Council has ever since delivered what was expected of them.

This legal trick was met with concern in the European Union, which Fidesz reacted to childishly by providing the European Commission with a translation that simply left out a few problematic parts. It also sparked the first real mass protests since 1990.

Orbán on air

Public broadcast radio and tv channels were the first victims, brought to their knees by a new leadership who swept out the old personnel despite the fierce resistance of journalists, some of whom kept protesting for months. Orbán has a regular interview spot now on Kossuth Rádió on Friday mornings.

The strive to break down any independent publishing has remained in full force ever since, and it wouldn’t be possible to enumerate all the steps. In part it is because most attacks are quite similar to the takedown of Klubrádió: extremely procedural, posing meandering administrative obstacles and finding obscure excuses to rid outlets of their broadcast rights or bleed them out financially.The country saw an expedited corporate capture of its publishing, as outlets were gradually acquired by the regimes clientele, who then enforce a political line, or sometimes simply close down the shop. The most prominent case of the latter was the sacking of the best selling political print daily Népszabadság, whose employees received their letters of suspension out of the blue on a Saturday morning in 2016, via motorbike curriers.

Other times, owners gave in: the then most read online portal Origo’s editor-in-chief was fired in 2014 and his staff followed in mass resignation, coinciding with its series of reports on corruption allegations against a top minister. The Hungarian branch of Deutsche Telekom owned the portal who soon after sold it.

Later that year the plan for an internet tax was announced which triggered even bigger protests nationwide and internationally. About a hundred thousand people marched on Budapest and many more throughout the country, which ultimately lead to a huge rise in activism and political engagement. The plan for the tax was withdrawn among widespread ridicule.

VillageHero from Ulm, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Government mouthpiece

Former Hollywood producer Andy Vajna, who moved back to Hungary to start a second career as government commissioner of the film industry under the illiberal rule, bought the second largest commercial television TV2 in 2015 and rapidly turned it into a government mouthpiece. With only the German-owned RTL left standing as a major independent tv company, Orbán attempted to break them with an advertisement tax, which inspired a lot of pushback. Not only did Angela Merkel give Orbán a bit of undressing, he also lost his oldest and most powerful ally to this attempt.

Fidesz founding member, former party treasurer and long-time and Orbán confidant Lajos Simicska built the original Fidesz media empire from the late 90s, amassing a major commercial news TV station, multiple radio stations, newspapers, and controlling a huge share of the outdoor advertising market. (He also happened to be a major builder as the owner of Közgép, a construction company that attracted a great many government contracts.)

The relationship came to a dramatic end when Simicska refused to sign off on Orbán’s plan to clip back his power in 2015 by the aforementioned advertisement tax. Then the 9th richest person in Hungary, Simicska called Orbán a ‘jerk’ on record (breaking it on Klubrádió, by the way). The oligarch declared he would fire the leadership of his media outlets. ‘I’ll throw out all the Orbánists’, he said, to turn the tide against the ever-expanding illiberal rule. And so hid did. Outlets which had always worked as openly partisan exchanged staff, signing famed critical journalists and providing platform to the opposition like no others had.

Enduring lengthy legal battles and the loss of his state concessions, the rebellious oligarch’s media empire uncovered unprecedented corruption scandals in the run up to the 2018 elections, leading to sustained national uproar. And yet, the hegemony of the client media seems to have delivered: the party regained its two thirds majority and prompted multiple investors, among them Simicska, to give up their media endeavours and withdraw.

The initial focus of this media war was on analogue and print media, targeting the elderly voter base who still remain the most mobilized in elections. In 2016, all county newspapers were systemically bought up and centralized in the hands of the regime’s favourite businessman, gas fitter turned state tender connoisseur, Lőrinc Mészáros, and an Austrian investor, Heinrich Pecina. (The same Pecina whom former vice-chancellor Hans-Christian Strache was talking about in the infamous Ibiza recordings, when dreaming up a media empire like Orbán’s).

Gigantic conglomerate

Commercial radios were also cut back on, leaving only one of them with national reach. The late Class FM, formerly owned by Lajos Simicska, lost its broadcast right in 2016 in a very similar way to Klubrádió’s Canossa: the National Media and Communications Council simply refused to prolong their right to the frequency and opened a new tender which Class FM was disqualified from.

No less than 476 media outlets were consolidated under the newly founded Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA) in 2018. Such a gigantic conglomerate should have qualified as illegal monopoly, however, a new law recognised the organisation as ‘of national strategic importance’, providing a legal exemption for the empire.

By 2020, only weekly print and online news hadn’t been dominated by Fidesz’s circles, while all county newspapers, 6 out of 8 dailies, 6 out of 10 radios and 6 out of 8 tv companies had been aligned with the centralised will, as ATLO Team reported. But the summer of 2020 saw the collapse of the biggest news site Index.hu in July, following the politically motivated sacking of its editor-in-chief and resignation of its entire staff. The original crew founded a new outlet since, and the owner of the now hollowed Index is now struggling to maintain its operations. In a country where journalists have lost most of their employment opportunities, it’s impossible to staff the portal that lead the market only half a year ago.

When media are overtaken, their sales and audiences tend to shrink, which means that audiences are not quite so easy to buy up. However, with a close to total takeover of the public sphere, more people without internet access, and entire regions have almost no access to anything else, than what the executive power allows for. This empire is financed mainly through state adverts, often including questionably favourable loans supporting major acquisitions. The rest of this megalomaniac oligarchy is also sustained in a similar vein, heavily relying on public funding channelled into private enterprises.

Viktor Orbán’s battle against Europe

Since the summer of 2020, the battle has been raging in the European Parliament: if the future post-Covid recovery plan, the fruit of tough negotiations between the Member States, make the granting of European aid conditional on the respect of democratic rules, Viktor Orbán’s Hungary has put a firm veto on this project. Backed by the Polish government, the nationalist-conservative leader precipitated a political crisis lasting several months, highlighting the tensions at work in an Union that is stumbling over fundamental values and the rule of law. Faced with Orbán’s obstruction, Germany, which led the EU Council until the end of 2020, has resolved to negotiate a compromise, allowing the Polish-Hungarian veto to be lifted. Is the Union yielding to autocrats? Michael Wech embarks on a road-movie across Europe to decipher this unprecedented crisis.

Wech follows the European deputy Daniel Freund in his investigation on the infringements of the rule of law and retraces the rise of Viktor Orbán to power, the way he extended his political and financial hold on the country – thanks in particular to the unscrupulous use of European funds – the way in which he ideologically radicalised his regime and how he managed to fool his European partners while remaining an unavoidable interlocutor.

Published 13 May 2021

Original in English

First published by Osteuropa (in German), VoxEurop (in English, Italian, French)

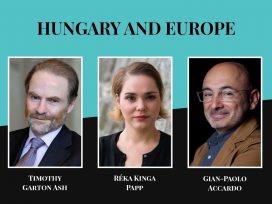

Contributed by Osteuropa, VoxEurop © Réka Kinga Papp / VoxEurop / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

In France, the censorship of pro-Palestinian positions is particularly severe, with antisemitism accusations increasingly being used by the far right. But behind the current wave of repression lies a set of attitudes that are neither new, nor exclusively rightwing.

In 2022, Shahd Abusalama, a Palestinian academic working in the UK, was suspended from her teaching position on antisemitism charges. Here she recalls the defamation campaign against her and discusses how her case reveals the structural vulnerability of Palestinians in the West.