Far more than in the past, urban space today registers the profitability of non-urban economies – the economy of the port, the mine, the plantation. Why and how? The key is the rise of intermediate services for firms: all firms today need more lawyers, accountants, insurance, and financial and consulting services than they did even 30 years ago. Thus a dynamic port will feed the growth of a very urbane professional class in whatever the major city servicing the port. Clearly, urban economies – professional services, design industries – also contribute to reshape urban space. Beginning in the 1980s and exploding in the 1990s, we saw a major shift from the Keynesian routinized city to the strategic city, which can range from regional to global. The rise of cities as strategic economic spaces is the consequence of deep structural transformations evident in all developed and not so developed economies. This is a subject I have developed at length elsewhere.

Here I want to focus on one particular aspect of this larger process: the partial urbanizing of a growing range of non-urban economic activities. Even firms in the most material economic sectors (ports, mines, factories, transport systems, construction) today buy more insurance, accounting, legal, financial, consulting, software programming, and other such services. These so-called intermediate services tend to be produced in cities, regardless of the non-urban location of the mine or the steel plant being serviced. Thus even an economy based on manufacturing, or a port, or mining will feed the urban intermediate services sector.

While this structural trend does not account for the whole urban economy, it clearly marks a novel phase for cities and urban regions, one that began in the 1980s. It brings to just about any material sector a growing number of high-income professional jobs (corporate lawyers, accountants, financiers, etc) and high-profit firms. This in turn has specific multiplier effects that become visible in urban space – not in the space of the actual port, mine, factory. Let me add promptly that it is mostly urban sectors that feed this process.

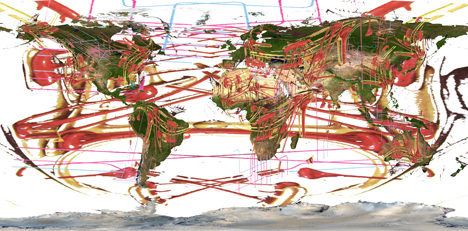

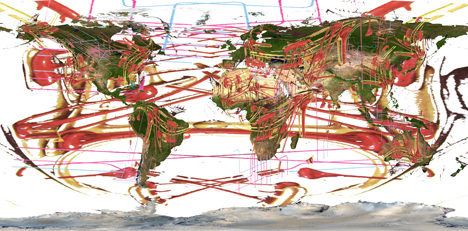

Hilary Koob-Sassen, still from “Transcalar Investment Vehicles”, Film London, FLAMIN Productions 2011; as featured on the cover of Saskia Sassen’s “Cities in a World Economy” 4th ed., Sage, 2012.

The key explanation is the rise of intermediate services for firms: all firms today need more lawyering, accounting, insurance, financial, and consulting services than they did even 30 years ago. Another part of the explanation is the rise of financial investments in all economic sectors, and this comes with a massive growth in the demand for contracts, guarantees and all sorts of provisions. It has further been escalated by the fact that both material economies and investors have become more globalized, further adding to the need of often complicated documentation and guarantees. Regrettably, cities left out of this structural development have tended to stagnate.

One way of capturing the deep bond between the port or the mine with the city is to say that far more so than in the past, urban space today registers the profitability of non-urban economies – the economy of the port, the mine, the plantation, the large factory. This link, along with more generalized city-specific growth, contributes to the renewed importance of architecture and urban design since the 1980s. Office districts, residential spaces, and the spaces for consumption and entertainment, all are at least partly reshaped by this direct link with profitable non-urban sectors.

The most common answers as to why cities have become strategic since the 1980s start with the notion of the ongoing need for face-to-face communications and the need for creative classes in the new economic sectors. Both are part of the answer. But in my reading, these are simply the consequences of the above-mentioned deeper structural transformation: the growing demand for intermediate services even in traditional economic sectors.

The growth effects of this trend are evident in a broad range of cities, from the provincial to the global. Firms operating in more routinized and sub-national markets increasingly buy these service inputs from more local or regional cities, which explains why we see the growth of a professional class and the associated built environments and new socio-spatial inequalities in provincial and regional cities as well as in global centres, which handle the more complex needs of firms and exchanges operating globally.

Thus the growing demand for intermediate services cuts across the binary that opposes heavy traditional economic sectors to advanced services, and it cuts across the binary that opposes the national to the global. These trends contribute to the growth in the numbers of global cities worldwide, which now is over a hundred major and minor global cities.

We see here, also a key counter-intuitive trend: no matter all the communication technologies and space-time compression (all realities that matter), the most advanced and globalized economic sectors continue to thrive through urban centrality. At the root lies the fact that the more globalized and digitized a sector becomes, the more its firms suffer from incomplete knowledge about their markets. Urban centrality enables the making of what I call urban knowledge capital – a collective production that is more than the sum of the knowledge of the professionals and the firms present in a city.

Beyond the basic fact of a growing intermediate economy located largely in cities, there are at least three dynamics that further explain the growth of the new intermediate economy. One of these is the growing complexity of central corporate functions when a firm is no longer local and begins to operate in a regional, national or global market. This holds for ports as well. Each of these expanded scales brings added market uncertainties, which become acute when operating in many different countries through shipping operations that connect with ports and their port cities worldwide. Such expansions also bring the need for firms to set up affiliates or other types of partnerships, further adding to the complexity of management operations.

This added complexity, in turn, brings with it a growing demand for intermediate services to handle central corporate functions of firms (and ports): rather than producing these in-house as was likely in an older era, they are now increasingly bought. In brief, firms increasingly buy a share of their central functions from highly specialized service firms: management consulting, accounting, legal, public relations, programming, telecommunications, and other such services.

Thus while even ten years ago the key site for the production of a firm’s central functions was the headquarters office, today there is a second key site: the specialized service firms contracted by headquarters to produce some of these central functions or components of them, and, generally, the global network of affiliates and partners these firms have and need. This is especially the case with firms involved in global markets and non-routine operations. But increasingly the headquarters of all large firms are buying more of such inputs rather than producing them in-house. Over the last fifteen years governments worldwide have also increasingly contracted for specialized and technical services, with ups and downs depending on economic recessions. And ports have become global operations that extend well beyond the actual port and need a growing range of specialized services and their networks of affiliates; in addition, most major ports today are also in the business of exporting a global knowledge economy, which mostly takes the form of managing other ports and advising on how to build or renovate a port.

Second, the specialized service firms engaged in producing the needed inputs for firms operating in complex and globalized markets are subject to agglomeration economies – and thus tend to concentrate in cities, even when the headquarters themselves they are serving have moved out of cities. The complexity of the services they need to produce, the uncertainty of the markets they are involved with either directly or through the headquarters for which they are producing the services, and the growing importance of speed in all these transactions, is a combination of conditions that constitutes a new dynamic for agglomeration economies. The mix of firms, talents, and expertise from a broad range of specialized fields means that a city functions as a complex information centre. Being in a city becomes synonymous with being in an extremely intense and dense information loop. This is a type of information loop that as of now still cannot be replicated fully in electronic space, and has as one of its value-added features the fact of unforeseen and unplanned mixes of information, expertise, and talent, which can produce a higher order of information; further, this is an environment that helps you “get” information you did not know you needed, always a critical dimension in complex work. This does not hold for routinized activities, as these are not as subject to uncertainty and non-standardized forms of complexity. Global cities are, in this regard, production sites for the leading information industries of our time.

A third major dynamic, derived from the preceding one, is that the more headquarters outsource their most complex and non-standard functions, the freer they are to opt for any location; this is particularly the case for firms subject to uncertain and changing markets, and hence a need for the speedy exchange of information. The reason is that much of the work subject to agglomeration economies is increasingly done by the new intermediate economy rather than by headquarters. In this regard, the key sector specifying the distinctive production advantages of global cities is the highly specialized and networked intermediate economy rather than corporate headquarters. In developing this argument I am contesting a very common notion that the number of headquarters is what specifies a global city. Empirically it may still be the case in many countries that the leading business centre is also the leading concentration of headquarters, but this may well be due to an absence of alternative location options. In countries with a well-developed infrastructure outside the leading business centre, there are likely to be multiple location options for such headquarters.

In short, the new intermediate economy of specialized services is, then, quite urban. It is one factor contributing to a novel dynamic for agglomeration economies. The original source of agglomeration economies was the cost of transport given the weight of key inputs. Today it is the costs of imperfect knowledge in an economy where managing speed and risk are critical. Where in the past such agglomeration economies would necessarily take on the territorial form of the centre – the CBD –today’s digital technologies and digitizing of economic activities would suggest that this type of territorial centrality is no longer necessary. And yet, the new dynamics feeding the advantages of agglomeration also thrive in central spaces.