When no female artists were nominated for the Grand Prix at the renowned Angoulême International Comics Festival in 2016, there was more than just an outcry among fans and artists. When the organizers justified their decision in Le Monde on the grounds that, unfortunately, there have only been a few women in the history of comics, the organization BD Egalité promptly responded with a list of 225 female comic artists as counterevidence, making the scandal all the more embarrassing.

Female comic artists have been shaping the international scene for decades. A number of them have continually devoted themselves to feminist topics, through analyses of power relations and sketches of images that subvert the prevailing gender order. The comic oeuvre of the French-Canadian illustrator Julie Doucet (born 1965) is considered a milestone in feminist art. The volume Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet brings together all of Doucet’s comics from between 1988 and 1998. This project of retrospection invites one to survey the feminist comic as a form, a synopsis that must also including three other notable authors – Anke Feuchtenberger, Nina Bunjevac and Liv Strömquist – each of whom emphasizes different aesthetics and topics in their work.

A mirror on gender order

Julie Doucet: Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2018

With disarming wit and without restraint, Doucet makes the female body the principal focus of her comics. When her series ‘Dirty Plotte’ – from which most of the comics in this volume originate – began to appear, her reputation as a woman illustrator was undoubtedly precarious. After all, the Québécois slang word ‘plotte’ means something like ‘cunt’ in English. With this provocative title, one can probably guess at some of the themes of her work: through her drawings, the illustrator pulls out a mirror, and in doing so reveals a rigid gender hierarchy concealed behind an ideology of cleanliness. By nonchalantly drawing attention to the everyday functions, needs and peculiarities of the female body, the illustrator undermines the power that suppresses and regulates female subjects, constantly defining taboos, and shifts that power to the body. The topics range from leg hair to bras, from masturbation to menstruation.

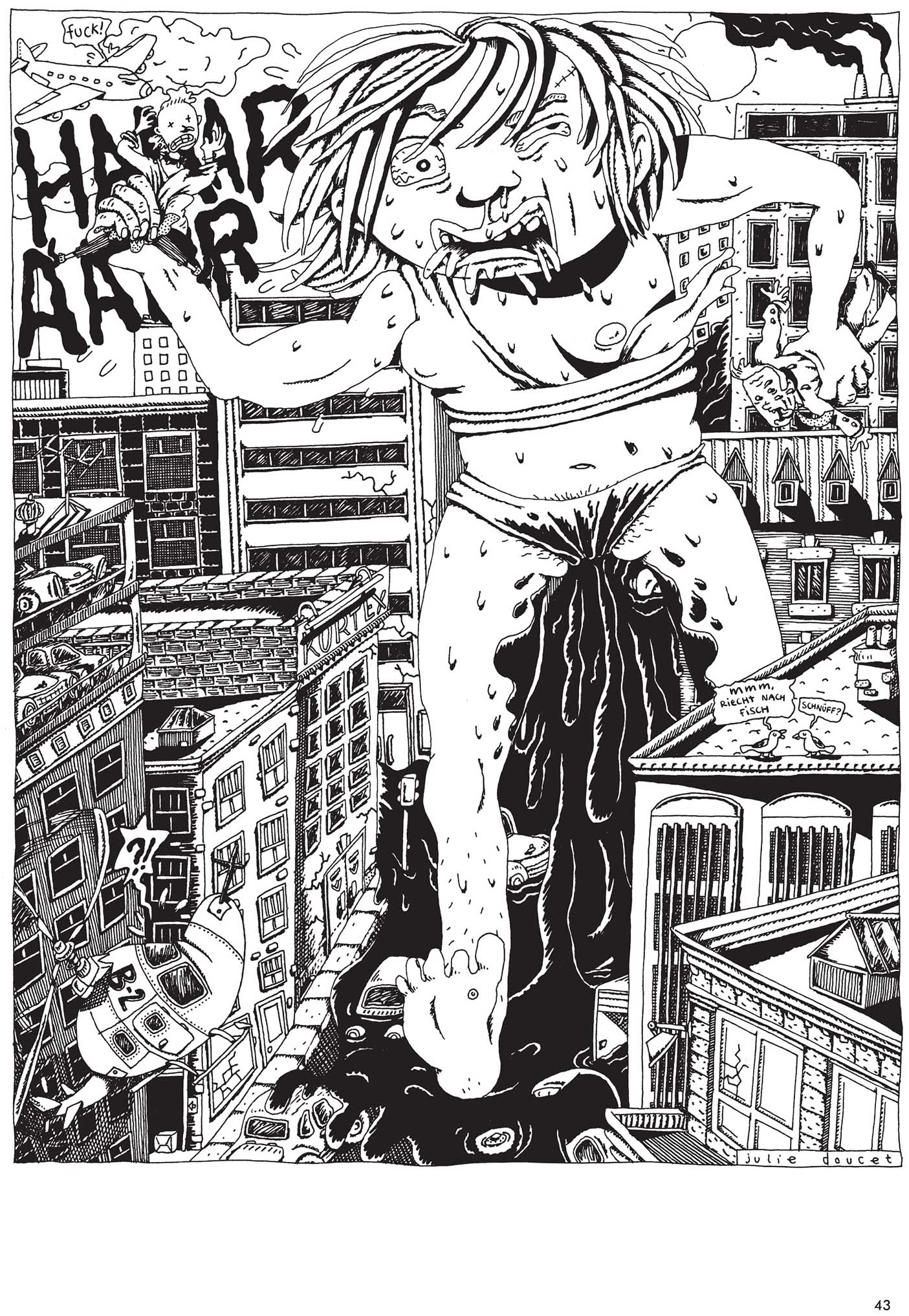

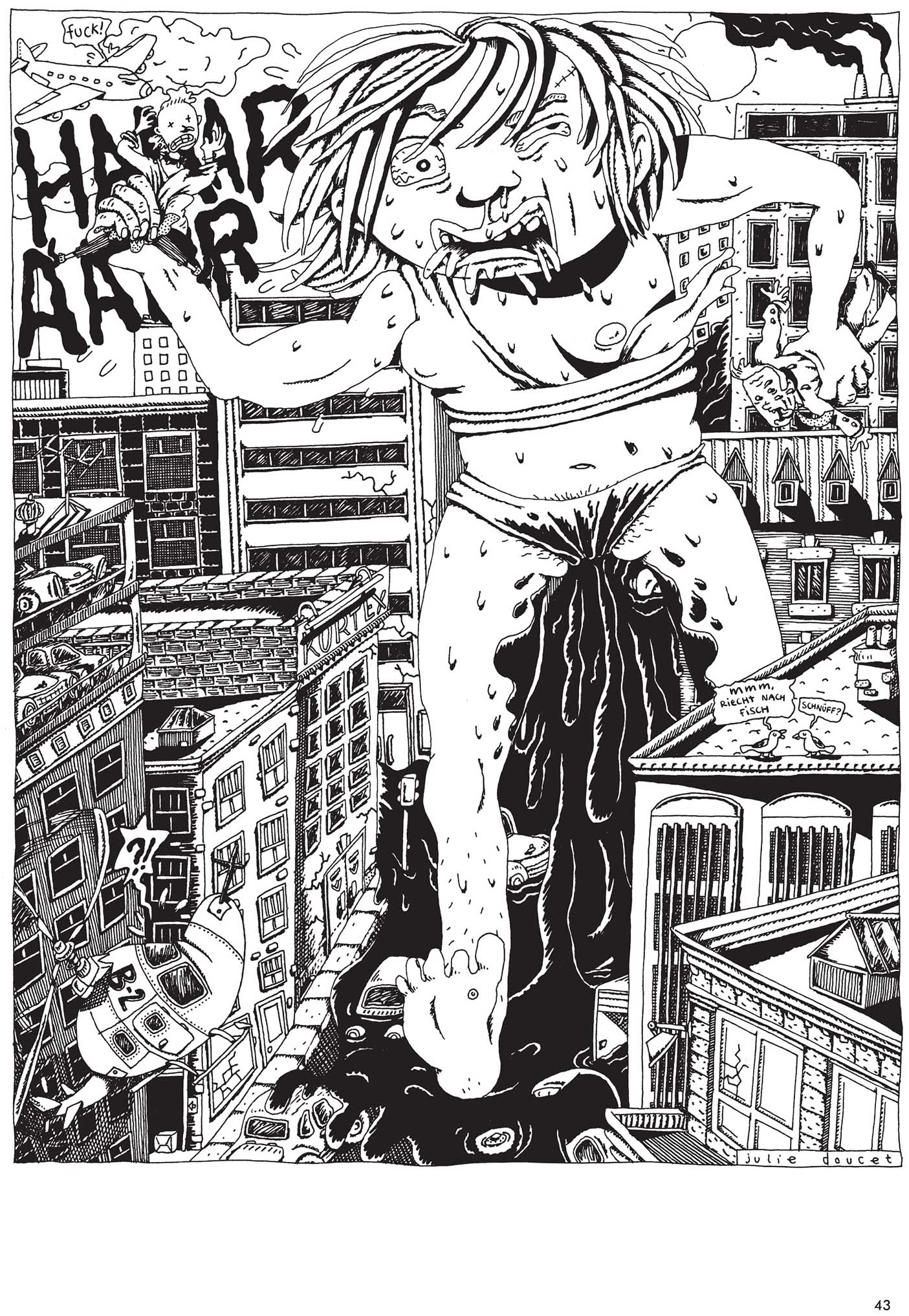

In one of the comics in the series, the protagonist, who shares the author’s name but is not straightforwardly her alter ego, wakes up with a saturated tampon – ‘… the slightest movement, and I will overflow …’ She deftly beams herself across the apartment into the bathroom. In contrast to this charming solution to the problem, Doucet draws a brasher version in ‘Heavy Bleeding’: This time when Julie cannot find a tampon at home, she flies into a frenzy and rages onto the street in her underwear, monstrously growing panel by panel like King Kong, clearing cars out of the way as her menstrual blood floods the streets like a waterfall. Two men writhe like worms in her hands. People with faces frozen in horror watch the incident, while others contend with the flooding.

What is pointed in this grandiose staging, this grotesque exaggeration, is the fact that this is the first time the female body’s potential unruliness and lack of restraint is depicted in the comic. As such, it has the effect of the dramatic satirization of a latent, ominous male nightmare of men’s loss of control over the female body. As Frederik Bryn Køhlert observes, Doucet engages in this Bakhtinian ‘carnivalesque subversion’ with relish. However, the illustrator also uses these kinds of staged dreams and surreal scenarios to explore the transgression of boundaries, from sexual transformation to castration. Her rough style of drawing, indebted to underground comic artists, can be characterized – in comparison with the ‘ligne claire’ (clear line) – as a ‘ligne crade’ or ‘dirty line’. With this dirty line, the illustrator challenges both the myth of the ‘dirty’ female, and that of the strong male. Reality, she suggests, is not a smoothly delineated world. Following a nightmare, Julie ironically praises ‘good old reality’, but the pictures show something different: the reality that surrounds her – furniture, kitchen appliances, etc. – is waging a malicious revolt against her (‘there you are’, these items taunt, ‘slut’, ‘shit’, ‘filth’, ‘die’). Reality is a daily nightmare that the character Julie attempts to ignore, yet this reality stands for (what seems to be) a mercilessly indomitable gender order, one on which Julie the author has declared war.

This article was originally published in Wespennest 180 (2021), featured in the Eurozine Review 9/2021.

Wonder and disturbance

A straightforward line can be drawn between Doucet’s ‘Dirty Plotte’ and the work of Anke Feuchtenberger (born 1963). Feuchtenberger’s comic trilogy W the Whore – with texts by the writer Katrin de Vries – similarly plays with attributions and projections. The first volume appeared in 1996, followed by W The Whore Makes Her Rounds in 2003 and W the Whore H Throws the Glove in 2007. As a centrepiece of her equally diverse and rich comic oeuvre, the series is one of the artist and professor’s most well-known. In July 2020, she was honoured for her life’s work with the Max and Moritz Prize, the most prestigious distinction for German comic artists.

Having grown up in East Berlin, Feuchtenberger only arrived at comics later in life, by way of poster art. She introduced the avant-garde legacy of the East into the comic medium and in many ways expanded it. Her comics elicit feelings of both wonder and disturbance. Her focus on women and the female body is combined with an interest in animals, plants and celestial bodies. W the Whore, a different character from episode to episode, does not behave like a stereotypical ‘prostitute’ in any situation – rather, the author destroys the associated subliminal images and deeply-rooted expectations of a ruling culture in which women are treated either as ‘whores’ or as ‘saints’.

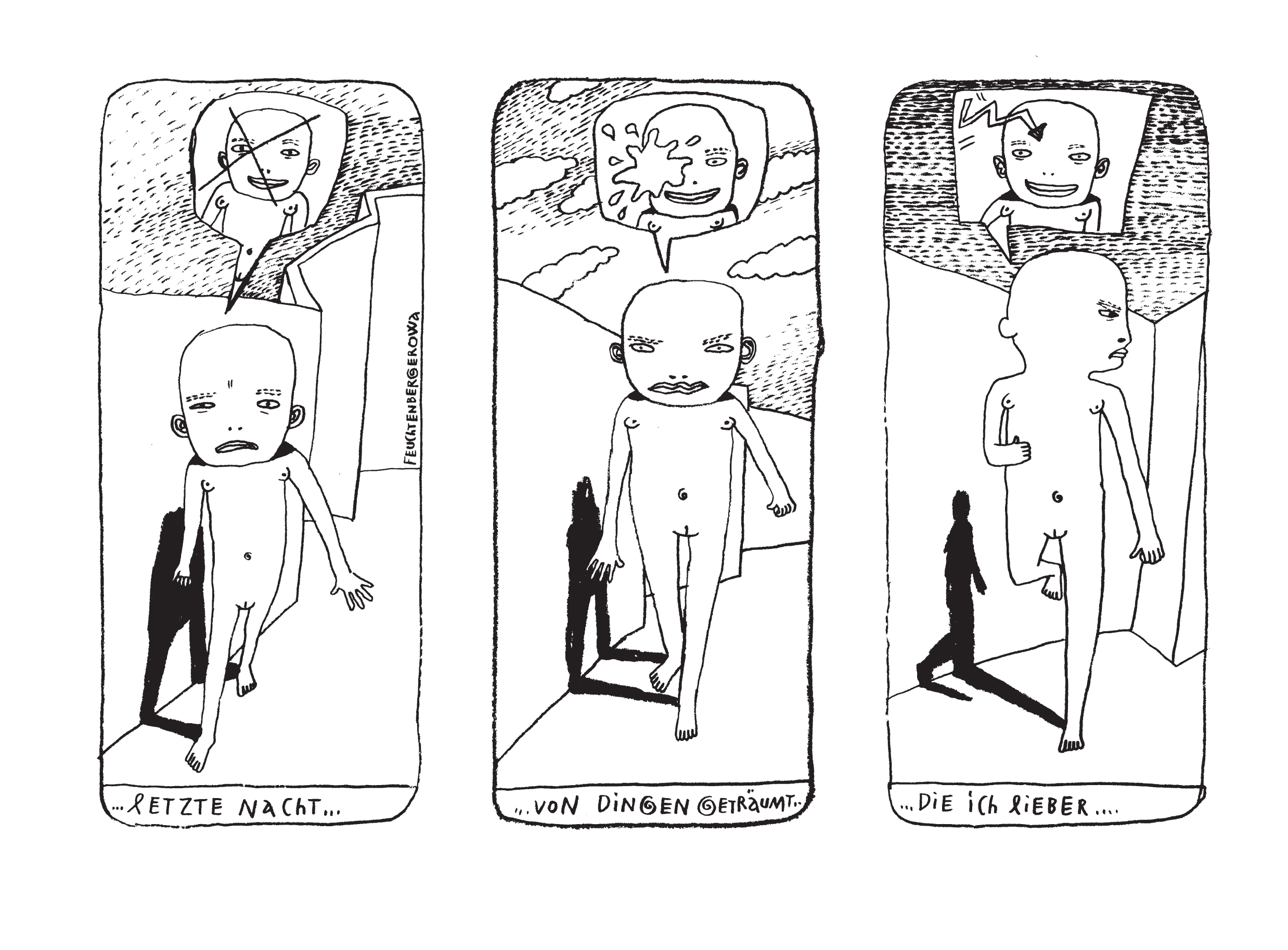

W the Whore has lost her desire. ‘I can’t recall it. I’ve forgotten.’ But desire for what? W the Whore goes to a party – she’s looking for someone. In the end, it’s a worm, not a man, that she takes home with her. Repeatedly, there are discontinuities in the comic’s expressions, in the images. Why does W the Whore, half naked, let her dress hang down? Why is she tying the chain around her stomach while her body is naked? The uncertainty is deliberate, because W the Whore – like many other characters in Feuchtenberger’s dream worlds – encounters prefabricated patterns, powerful social structures that she would like to co-opt and assimilate. But these patterns and orders are random, questionable and replaceable. Breaking up, expanding and exploring are part of Feuchtenberger’s process. Her comics are treatises, ‘graphic essays’. The clear drawings, pencil on paper or charcoal on canvas, leave a lot of free space, white surfaces creating contrasts between darkness and luminosity.

‘I think that when contemplating my pictures and stories, one would have to embark on a kind of dream-like hike,’ said Feuchtenberger in a recent interview. She had already raised the idea of sleepwalking with her 1998 volume Somnambulist, which, like the 2001 volume The House, follows the lives of kindred female figures. Each of the thirty episodes in the ‘House’ series provides a key for reading the text. The specific combination of text and image is reminiscent of the baroque style that Feuchtenberger inscribed onto the modernistic comic. Here, body parts are lined up like objects, or architectural elements, alternating with the word fragments of a sentence that has been broken down into its various parts. This sentence holds the erratic picture elements together and unexpectedly reveals traces of collective memory. ‘The sex /’, it states in the strip about the female sexual organ, ‘pulsates / the penetrating / hermetic / enclosing’. The sentence provokes the making of a multitude of connections between thoughts and memories, including the image of abyss in the final panel, where a female figure is ‘hermetically enclosed’ by boiling water as she hangs from a cauldron over a fireplace.

Drawing sexual violence from the abyss

The comic Bezimena, a modern adaptation of the myth of Artemis and Siproites by Nina Bunjevac (born 1973), also leads the reader into an associative abyss. Bunjevac, a Canadian-Yugoslavian illustrator, first became known for her autobiographical comic Fatherland (2015). In Bezimena she tells a story of male violence against women, and in doing so achieves a powerful dramatic impact. Here Greek myth forms a backdrop for a matrix of numerous allusions. As a punishment for seeing (or watching) her naked as she bathes, Artemis, goddess of the hunt and guardian of women and the young, transforms the youth Siproites into a woman. This also recalls the more well-known mythological tale in which it is Actaeon the hunter whom Artemis transforms into a deer following a similar encounter. Actaeon is then hunted and torn to pieces by his own dogs. Bunjevac turns these myths on their head: Bezimena, ‘the nameless’, having been disturbed by a priestess in contemplating something trivial, abruptly plunges the head of the priestess into water, transforming her into a man. This, however, is only a framework for the comic; its main subject is the boy’s subsequent life.

From a distance, Bunjevac’s large-format, full-paged hatched drawings look like crudely pixelated black-and-white photos of brittle beauty. The narration takes place in a distant location, coming from celestial bodies in the nocturnal firmament. Speech bubbles on the book’s left-hand pages are sharply separated from the drawings to the right. The many close-up shots create a vortex-like suction effect. In between, blank black pages open up breathing space – another evocation of abyss as the boy’s story develops at a pace that chases the viewer across the pages, as though in a film noir. This is a story of a sexual obsession. Though the vice of masturbation is forcibly driven out of little Benny, he later discharges his instinctual desire in a devastating way. In doing so, he is only following instructions he has found in a notebook. Or was it all just the product of a delusional imagination? In a series of surreal nightmares, Benny transforms himself into a deer, and in interludes Artemis’s bears dance across the pictoral stage. The circular dance, however, comes to a sudden stop; the police are in Benny’s apartment. Convicted of the rape and murder of three girls, Benny at that moment wants to hang himself…

Without prior warning, the reader is re-confronted with the narrative premise. The gender transformation, it transpires, was only temporary, the story itself just a wrinkle: Bezimena now pulls the priestess’s head out of the water, helplessness and horror written on her dripping face. ‘Who are you crying over?’ Bezimena asks. Though the question concerns the priestess’s plaintive wailing over the conviction, it takes on a new dimension with the horrifying threat of sexual transformation. While this is technically the end of the comic, Bunjevac does not let her readers depart just yet. In a ‘note’ at the end of this complex graphic frame story, the author adds another interpretative dimension. Here, she describes how, as a 15 year old, she herself experienced sexual violence in a Serbian village. As such, it is reasonable to read Bezimema as a surprising contribution to the #MeToo debate.

Stubborn taboos

This motivation notwithstanding, Bunjevac’s multi-layered, cramped graphic novel lingers in a limbo of ambivalence. This marks a stark contrast – at least at first glance – with the unambiguous comics of Swedish artist Liv Strömquist (born 1978). By the time Strömquist’s anthology Fruit of Knowledge was published in 2014, the trained political scientist was already an international star of the feminist comic scene.

The volume contains a brilliant cultural history of the vulva, in which the illustrator introduces, in a punk style – one that is as well-established as it is subversive – the arsenal with which philosophers, doctors, scientists and other proponents of a patriarchal discourse have been working for centuries to make the ‘female sexual organ’ invisible, belittle it, domesticate it, or reduce it to a vaginal slit.

Strömquist’s comics are as much intrepid polemical pamphlets as they are piercing and analytical comic essays, whether she is addressing structural changes in relationships, as in Prince Charles’s Feelings (2010), pursuing the disenchantment of the male genius cult, as in I’m Every Woman (2019), or questioning the ability to love under late capitalism, as she recently did in The Reddest Rose Blooms (2020).

In addition to exuberant wit and inexhaustible satirical ideas, the author also has an outstanding ability to convey complex theories in an understandable manner. With virtuosity she juggles quotes from science and literature, popular culture and mythology. Her comics feature conversations from Plato’s dialogues alongside modern TV interviews, Rumi poems and lyrics by Beyoncé. In breathtaking manner, Strömquist facilitates discourse between centuries.

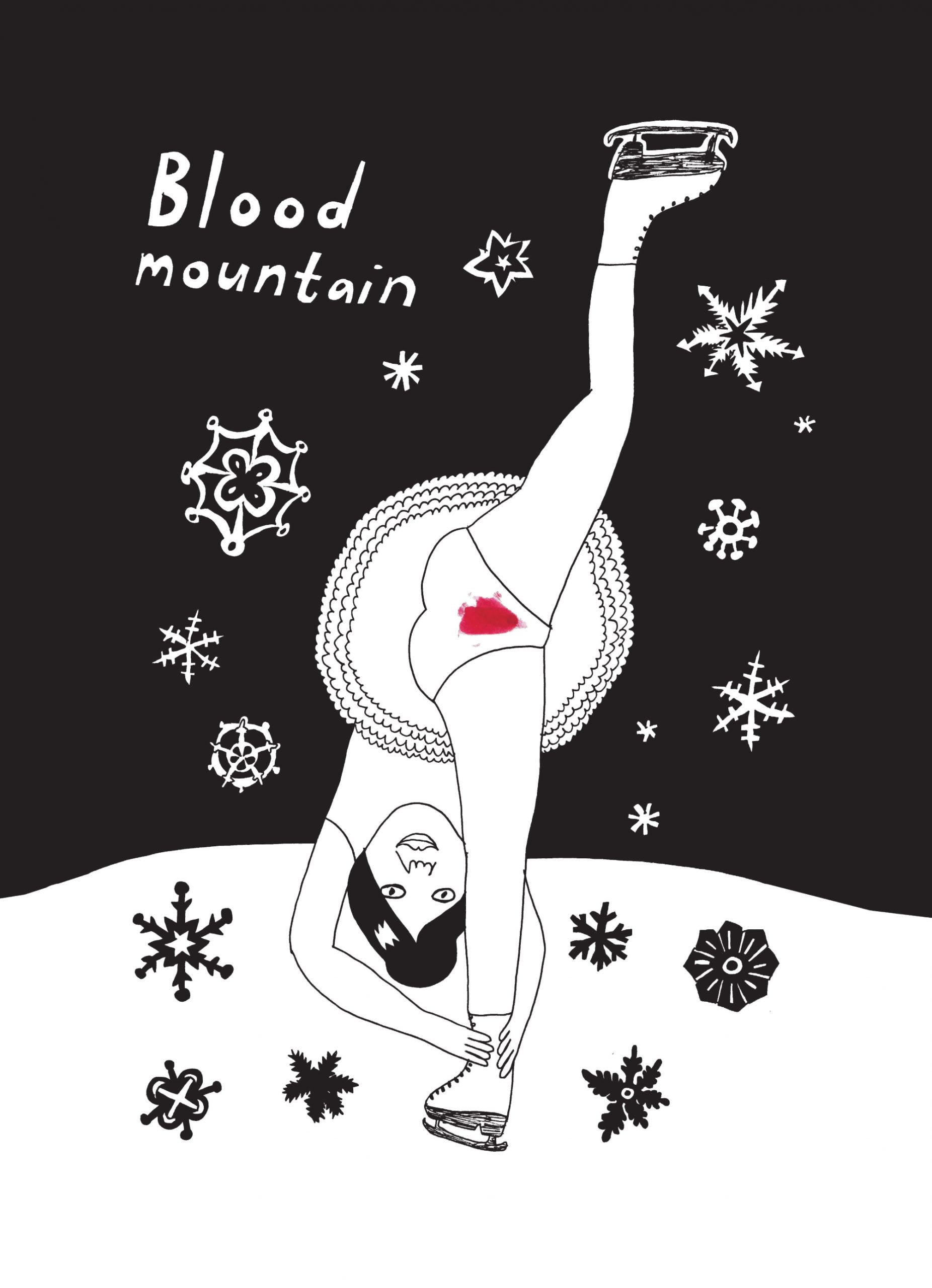

Despite her polemicism, however, Stromquist is equally concerned with discontinuity, transformation and, to an extent, ambivalence. Again and again she juxtaposes positions and theories without necessarily offering a solution. She pauses and interrupts herself, raises doubts: ‘It COULD be that way!! But doesn’t HAVE to be. / Just stay calm!’ Through an unauthoritative style of disclosing of her own reflections, she encourages others to think for themselves, and in this sense shares common ground with Doucet, Feuchtenberger and Benjevac. In one remarkable picture, Strömquist incorporates Doucet’s work into her own. A good quarter of a century after Doucet’s treatment of the topic, menstruation – even having been made ubiquitous by commercialization – remains a taboo, still capable of having a jarring effect on the public. The ice skater Strömquist renders in black and white in Fruit of Knowledge can be seen as an homage to the raging Julie: drawing an arabesque with her legs apart, the skater reveals a red spot in her crotch. A graffiti version of the dancer was exhibited as an installation in a Stockholm subway station between 2017 and 2019. It showed a young woman sitting down relaxed with her legs open: ‘It’s Alright (I’m Only Bleeding)’.

Bibliography

Julie Doucet, Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet, Montreal: Drawn and Quarterly, 2018

Anke Feuchtenberger, Das Haus, Berlin: Reprodukt, 2020

Anke Feuchtenberger, Katrin de Vries, W The Whore (trans. Mark David Nevins), Antwerp: Bries, 2001

Anke Feuchtenberger, Somnambule, Berlin: Reprodukt, 2019

Nina Bunjevac, Bezimena, Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2019

Liv Strömquist, Fruit of Knowledge, London: Virago, 2018

Liv Strömquist, I’m Every Woman, Berlin: avant-verlag, 2019

Liv Strömquist, The Reddest Rose Blooms: Romantic Love from the Ancient Greeks to Reality TV, Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2021

Liv Strömquist, Prins Charles Känsla, Stockholm: Ordfront Förlag, 2019