Italy has united behind Matteo Salvini’s League to the extent that the party has effectively overtaken Marine Le Pen’s National Rally as the largest contingent in the new rightwing populist group, the European Alliance of Peoples and Nations.

Divisions old and new have shaken up the compelling semblance of stability accomplished in Germany since reunification. While the Green surge is most noticeable in the western states, the electorate in eastern ones continues to be drawn to the far-right. Whether outgoing Chancellor Angela Merkel can save face as Berlin loses its influence in Europe remains an open question.

Meanwhile, authoritarian tendencies in Slovenia are shaping a somewhat fearful new normality as the creeping polarization of public life intensifies.

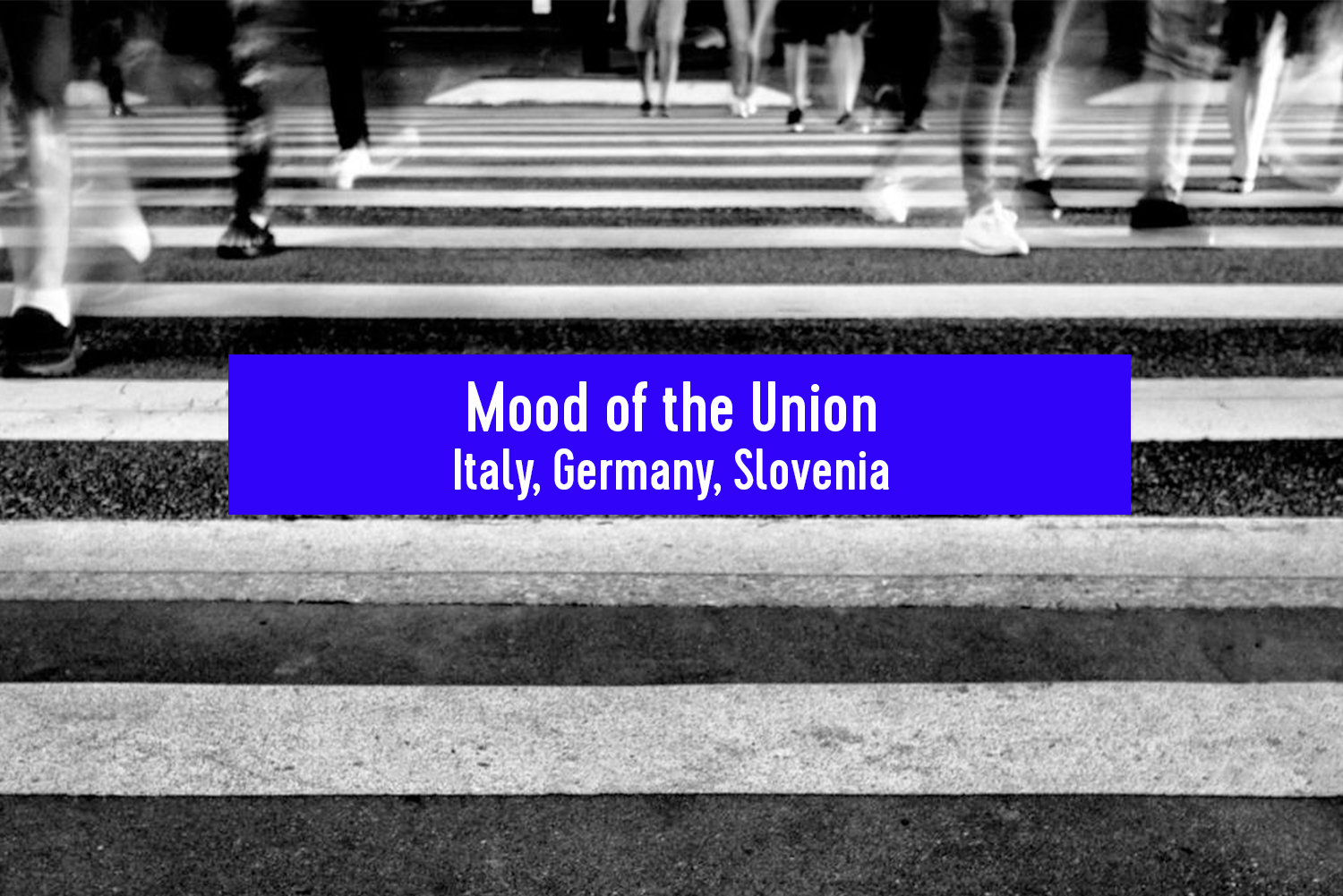

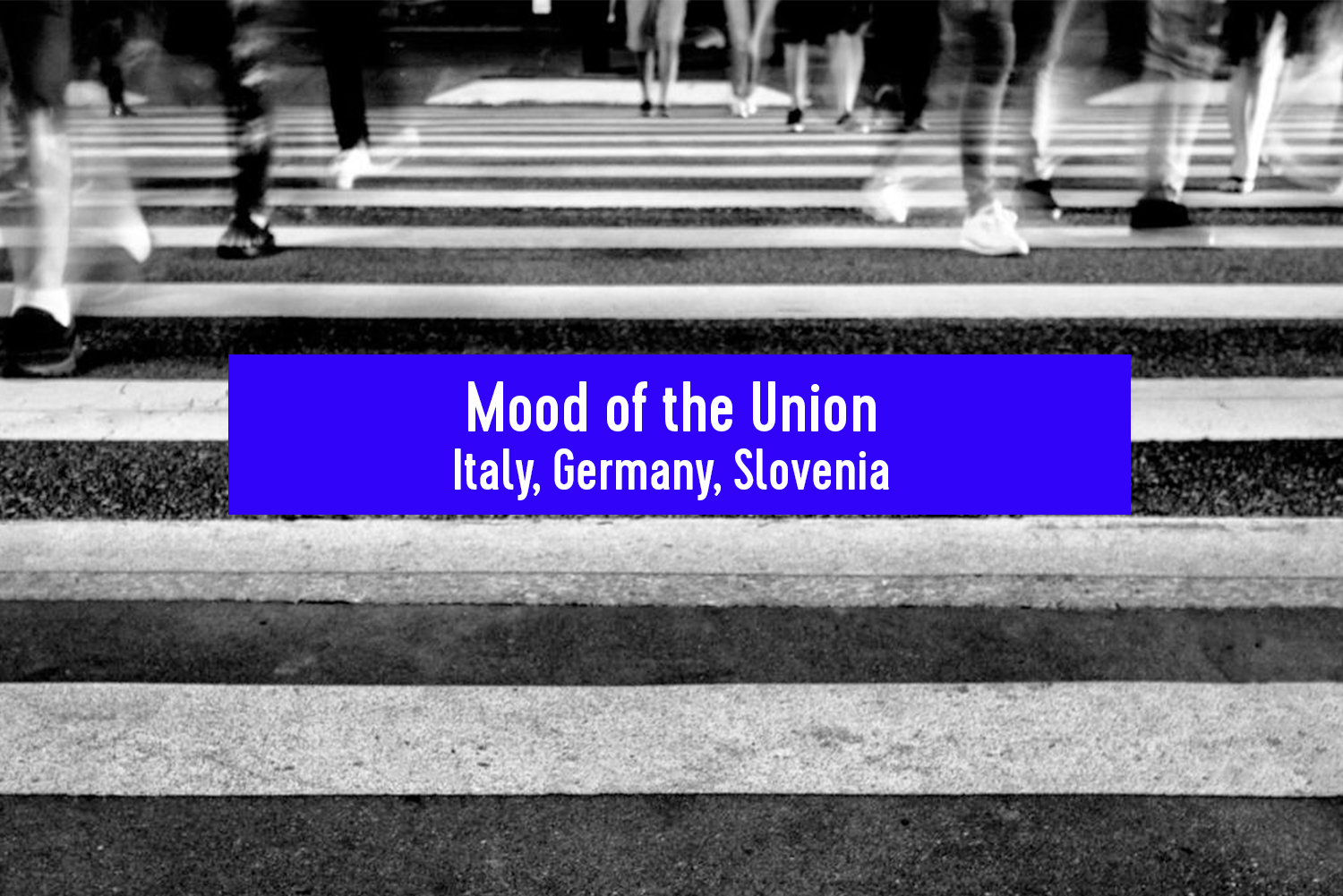

Photo by Isable Naiara Matilde on Pexels

Why does Italy keep turning right?

Sofia Francescutto, contributor, Il Mulino, Bologna

After four days of elections, Europe has woken up to a political order that contradicts those who feared a crushing populist and nationalist victory. The parties that took an anti-EU line in the campaign did not secure sufficient support for their common plan of dismantling the Union from within. Having lost seats to Liberals and Greens above all, the center-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the center-left Socialist and Democrats (S&D) still remain the two largest blocs in the European Parliament. Nevertheless, MEPs of an anti-EU and eurosceptic persuasion will now occupy almost 20 percent of the seats there.

Among the countries that could not resist the allure of political leaders claiming to claw back power for the nation, Italy, France and the UK came to the fore. While many British voters remained (stubbornly) faithful to the path they chose three years ago, France now faces the consequences of recent protests against Emmanuel Macron. Voters expressed a preference for Marine Le Pen over the French president, who was defeated by the nationalists by a small but symbolic margin. Yet among the leaders who considered the European elections a test for their popularity at home, Italy’s rightwing leader Matteo Salvini has to be the most satisfied.

The deputy prime minister has revealed an admirable ability to secure the backing of public opinion and been rewarded with 34.3 percent of the vote. Five years ago the League received just 6.2 percent, now it is the country’s first choice. Salvini secured the best results in the north of Italy (40.7 percent), where the League’s earlier campaign for autonomy and independence from the South begun to attract voters in the early 1990s. Back then, the political father of the League, Umberto Bossi, would refer to southern Italians in less-than-respectful remarks, prompting a general intolerance toward immigrant workers moving from the South to the North.

Italians first, everything else second

This time round, with 23.6 percent of the vote in the South, the area’s six regions contributed significanlty to the victory of a party that once wished to see them as parts of a separate state. Nonetheless, the League remains second in the South, where the Five Star Movement won 29.2 percent. The latter’s success can be linked to its support for a citizen’s income, with Campania for example accounting for 16.3 percent of applications for the benefit made across the country. This was also the Region where the Five Star Movement secured its best result, winning 34.8 per cent of the vote.

Currently led by Luigi Di Maio, who serves as a deputy prime minister along with Salvini, the Five Star Movement took 17.1 percent of the overall vote in Italy, just over half of the share that brought it to power in last year’s national election. Due to celebrate its 10th birthday this year, the Movement has paid the price for its political inexperience as contrasted with the approach of the practiced career politician Salvini.

Also Italy’s interior minister, Salvini spent his campaign having selfies taken, repeating coarse slogans and launching social media games like Win Salvini. According to critics, the campaign was also allegedly punctuated by the misuse of state flights in order to reach some of the country’s more locations. The general line of criticism presents Salvini as a politician who will soon be unmasked for oversimplifying matters that demand a deeper understanding. Leftwing parties in particular imply that the Italian people have been fooled and become blind to their own needs and interests. Unfortunately, there is nothing more counter-productive in politics than saying potential voters are wrong or stupid.

This is pretty clear to Salvini, who owes his success to an ability to identify sensitive topics, understand popular needs and, most of all, show that he listens to those who share them. This means focussing obsessively on two topics, immigration and security, condensed into a slogan that may sound familiar: ‘Italians first’ (which became ‘Italy first’ during the European elections). Everything else comes second. Employment, welfare and education are not exactly priorities but rather issues that will solve themselves once we are done with the security issue. The basic idea is well known: there is an enemy and we need to fight it. Salvini makes his case on a weekly basis against immigrants, gypsies, journalists, political opponents, bureaucracy, banks, the European Parliament, legal cannabis. Anything goes as long as it keeps alive the polarization between an outside and the inside, between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

When numbers make no difference

Contrary to the claims of many critics, Salvini did not create this polarity. He simply took advantage of it. It is a fact that globalization, climate change, wars and conflicts are changing the dynamics of the world population and its distribution. Whether an intrinsic characteristic of human nature or a reaction to historical contingencies, the general perception in Italy is that there is something unknown and potentially dangerous that needs to be kept under control. Leftwing leaders tend to ignore the fact that numbers make no difference. Fear requires heroes, not numbers. Salvini knows it and proudly demonstrates his power to prevent certain boats docking in Italian ports with a single phone call.

The election results in Riace and Lampedusa speak for themselves. Once a symbol of integration and hospitality, Riace turned out to be tired of migrants and granted Salvini’s party with 30.8 percent of the vote, advancing on the League’s 0.9 per cent in 2014. It was a similar story in Lampedusa, Italy’s southernmost island and the backdrop to the award-winning migration documentary Fuocoammare. Five years ago the League won 16.9 percent of the vote here as compared with the 45.9 percent that ‘Captain’ Salvini, as he is often called, won last week.

Meanwhile the young, educated Italians emigrating abroad in search of better opportunities will soon outnumber new arrivals tying to escape death and poverty. But this will not alter people’s fears as jobs are lost, rents and prices rise, businesses close, taxes increase and poorer, more desperate people continue to arrive. Italy is turning to the Right because there is no Left responding to these fears before trying to say there is nothing to be afraid of.

In search of a new path

This general perception is particularly deep-rooted in the suburbs and provinces, where education levels are lower and poverty more pronounced. Here, Europe is often seen as a distant, bureaucratic and expensive institution that is partly responsible for the general crisis. Hence the clear contrast between the provinces and the urban centres where globalization and its opportunities are better understood. Thus the Democratic Party comprehensively prevailed in cities like Rome, Milan, Palermo, Turin and Florence but lost out to the League almost everywhere else.

While the Democratic Party did slightly improve on its performance in the 2018 national election, it has yet to make any real comeback. Under Matteo Renzi it won 40.8 percent of the vote in 2014. But Renzi then became conceited, leaving the party’s current leader Nicola Zingaretti with little time to make his mark in a media landscape dominated by Salvini.

Italy is now just as paralyzed by Salvini’s omnipresence and gall as it was by Berlusconi’s. The good news is that even though Italian voters tend to be excited by these kinds of characters, they are just as likley to become annoyed with them when they fail to serve the electorate. If only leftwing parties would stop trying to catch up with their opponents by merely following their every move and, instead, start to build a new path that shows how important Europe is to solving real problems – then we might start moving forward again.

This is an edited version of an article first published online in Il Mulino here.

A deeply divided Germany

Steffen Vogel, Editor, Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik, Berlin

This European election has really shaken German politics. The outcome will shape domestic political debates for months to come. Three main aspects are at play. First, there is Germany’s decisive part in the ‘Green Surge’ that took Europe by surprise. A good showing of the German Green Party had been widely expected domestically but the size of the upswing was more than the party’s strategists had dared to dream: with 20.5 percent, the Greens almost doubled their share, taking millions of votes from Social Democrats and Conservatives alike and coming first at the polls in some rural areas.

Such an unprecedented upsurge reflects a massive change in public discourse. Since the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, the far-right had dominated the agenda for some time by agitating against refugees and open society as a whole. But beginning with a huge demonstration in Berlin last October, when about 240,000 people marched for openness and solidarity (the slogan was ‘unteilbar’ or ‘indivisible’), the discourse began to shift. And since the weekly ‘Fridays for Future’ climate protests kicked off, the dominant issue in German public debates is the fight against the looming climate catastrophe. With their pro-European, pro-diversity and ecological stance, only the Greens have been able to capture this mood.

The ebb and flow of influence

Yet the second point to note is that the political turnaround obviously does not apply to the whole of Germany. While the Greens could now be ready to gain the status of a major party with a strong base in western states, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is the strongest force in large parts of the eastern states. As the country marks the 30th anniversary of its reunification, it thus remains deeply divided along old borders. This feels all the more shocking to many after the connections between the AfD and violent neo-Nazis became openly visible during racist riots in the eastern town of Chemnitz in summer 2018.

Third, Germany’s position in the European Union is facing more and more challenges. After almost a decade of playing a hegemonic role, Berlin seems now unable to help the conservative lead candidate Manfred Weber into the position of president of the European Commission. This can certainly be interpreted as a reaction to Berlin constantly blocking European reforms in the past years – a policy which also drew harsh criticism at home. Chancellor Angela Merkel may now have to secure another respectable top job for Germany in order to save face. With regional elections in eastern Germany ahead, German politics is now in flux.

Authoritarianism and ‘normality’

Boris Vezjak, Editor, Dialogi, Maribor

Janez Janša’s Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) and the Slovenian People’s Party (SLS) are the winners of EU election in Slovenia. Their joint list received a rather convincing 26.4 percent of votes, thus winning three out of eight MEP seats. Two coalition parties, the Social Democrats (SD) and the Marjan Šarec List (LMŠ), secured two seats each with 18.6 percent and 15.6 percent respectively.

Janša’s success is relative when one considers that he received less than three fifths of the support that the opposing coalition parties attracted between them. Nonetheless, this is the third consecutive success for the SDS in a short period of time. Last year Janša, a strong and devoted ally of Hungary’s hard-line Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his ruling rightwing Fidesz party, won the parliamentary elections. Notwithstanding which, he was unable to form a coalition after the current prime minister, Marjan Šarec, formed a minority government with moderate liberal groups. Later on in 2018, the SDS also obtained the most mayoral posts in local elections.

Under the veil of normality

For now, Slovenian imitators of Orbán appear to be victorious, but not entirely politically effective. In contrast to the prevailing rhetoric in Hungary, intense talk of Christian values and their importance to European identity was lacking during the campaign here, as this would presumably have benefitted the Christian democrats in the party Nova Slovenija, which won 11.1 percent and one MEP seat.

Orbán illicitly financed the SDS’s parliamentary campaign in 2018 and is also indirectly investing in Janša’s media operations. In his speech only a week before EU election day he stressed that neither Slovenes nor Hungarians want illegal migration and that both countries need strict border control. After that he openly declared a long friendship with SDS MEP Milan Zver.

The relatively peaceful course of the electoral campaign was marked by anti-immigration slogans and extensive fear-mongering, predominantly focused on the thrilling story of four refugees who kidnapped a local farmer at the Croatian-Slovenian border. In general, the country remains politically polarized, trapped between authoritarian tendencies and repeated efforts to combat them. Such efforts are mostly made under the veil of ‘normality’ by those leading liberal and centrist politicians who are attempting to put an end to Janša’s dominance.

‘Mood of the Union’ is published by Eurozine and sponsored by the ERSTE Foundation and the National Endowment for Democracy.