Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

An invasion in the making: why Russia’s intentions were apparent back in 1991. Also: the Kremlin’s military and political miscalculations – why bigger is not better; and resistance in Kherson – how the city survived despite everything.

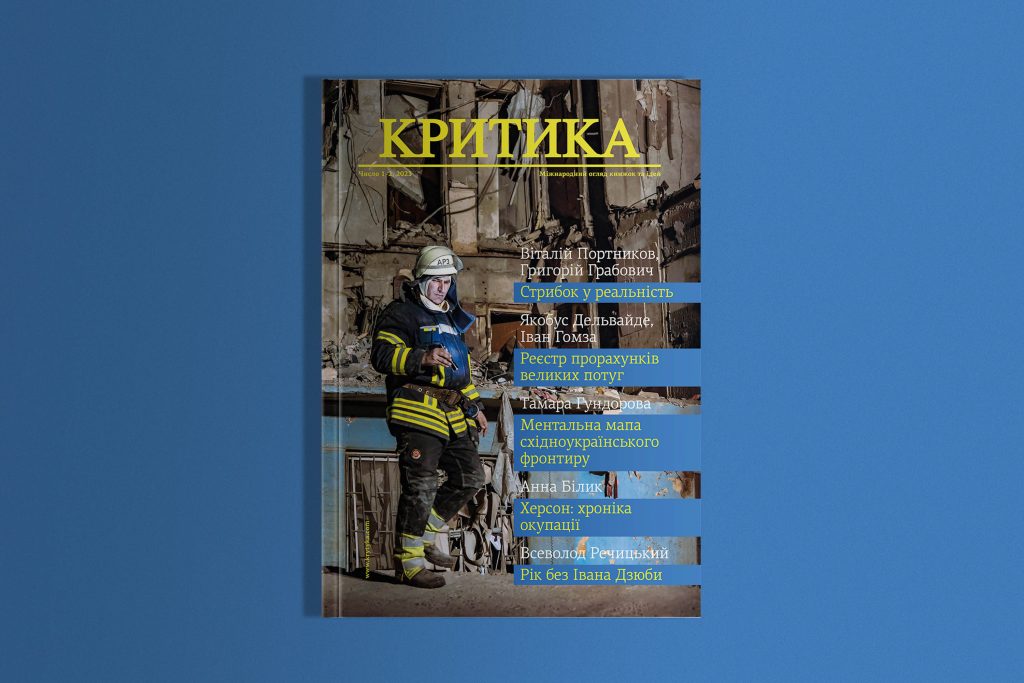

In the latest issue of Ukrainian journal Krytyka, the journalist Vitaly Portnikov argues that Russia has gradually been moving towards the full-scale invasion of Ukraine ever since the country’s independence in 1991. However, like in the film ‘Don’t Look Up!’, Ukrainians refused to look up and acknowledge the metaphorical meteor that was heading right for them.

Even immediately after Ukraine’s independence, Yeltsin’s press secretary stated that if allied relations with Russia’s neighbours deteriorated, it ‘reserves the right to raise the issue of border revision’. Russia did what it could to keep Ukraine in its orbit, but the Orange Revolution of 2004 threw Russia’s plan off course by overturning fraudulent elections granting victory to Russia’s candidate of choice. Russia was highly critical of the revolution but hoped that that the defeated Yanukovych had enough support to make a comeback, and in the meantime successfully blocked plans for Ukraine’s NATO membership.

Things went according to plan: Yanukovych was later elected. But a decade later Ukraine again departed from Russia’s script. ‘The victory of the second Maidan scared Putin,’ writes Portnikov, ‘because this time the Russian president didn’t see potential for a revanche, or the possibility to stop the signing of the association agreement between Ukraine and the EU.’ And so Putin decided to cripple Ukraine by occupying territory in the south and east, which he thought would be enough to permanently thwart Ukraine’s EU and NATO ambitions.

But what triggered the escalation to full-scale invasion in 2022? Portnikov believes it was partly the Kremlin’s realization that the Ukrainian president Zelensky, elected in 2019, would not capitulate; and partly US president Biden’s announcement that the occupation of Crimea and the Donbas may not prevent Ukraine from gaining NATO candidate status. Again, Ukrainians took little notice, but this was likely an ‘alarm bell’ for the Kremlin, which resolved that the only way to stop Ukraine permanently sliding away from Russia was to occupy the country.

There had been signs Russia had been prepared to take such radical actions all the way back in 1991, Portnikov points out. But Ukraine failed to take action to defend its autonomy. Now, with the onset of full-scale war, Ukrainians are living in reality. The only way to permanently thwart Russia’s long-held ambitions is for Ukraine to liberate its territories and become a member of NATO and the EU. Otherwise, the country is ‘destined to be a territory of new bloody battles, a buffer zone of civilisational conflict’.

However, it was not just Ukrainians who misjudged their opponent’s motives in this war. Ukrainian political scientist Ivan Gomza, writes about Russia’s hubris: ‘The mistake of the Russian political leadership is that it overestimated its own strength, whilst ignoring the values and norms of the international community.’ The Kremlin did not expect Germany to divert its energy from Russian sources, or the likes of neutral Switzerland to join in sanctions, and countries such as Poland to take hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees.

The Russian leadership – as well as pro-Russian commentators – underestimated not only the Ukrainian armed forces, but the Ukrainian state as a whole. Russia placed too much faith in its own firepower and rigid, top-down military structures, believing that ‘bigger and better aircraft would compensate for errors in logistics and planning’. However, they were mismatched when faced with Ukrainians waging ‘modern warfare’: small, mobile groups of Ukrainian forces, where junior officers were empowered to take their own initiative. Confident in their own might, Russian forces were not ready to face a mobile and dynamic enemy that was armed with technology such as Javelins and NLAWs – and knew how to use them.

Ukrainians have not only been fighting back with military means. In ‘Hell game,’ Anna Bilyk writes about Ukrainian resistance on the ground in occupied Kherson. A professor at Kherson Technical University, Bilyk has been living in Kherson throughout the full-scale war. ‘It became clear: they’d come to kill us,’ she writes of Russian forces entering the city in February.

The occupying regime quickly tried to subdue the local population with Stalinist repressions and propaganda. Kherson’s residents were subjected to door-to-door searches, and those walking the streets were vulnerable to arrest and questioning. Anyone showing a pro-Ukrainian position or ties to the government or military ran the risk of ending up a prisoner in a basement. Billboards occupied the public space proclaiming ‘Kherson – with Russia forever’, and radio stations and TV channels broadcast wall-to-wall Russian propaganda. The currency was changed, shops re-named, and the threat of torture was used to make people take down Ukrainian flags.

But ‘despite everything,’ Bilyk writes, ‘the Russians were resisted and ignored.’ Kherson residents fought back, in big and small ways. Thousands actively resisted occupation, joining street protests in the spring. When these were dispersed, the ‘yellow ribbon’ movement clandestinely posted Ukrainian symbolism across the city. Residents refused to work for the regime, with Russia’s constant job advertisements going unanswered.

Residents also refused to give up their national currency: even market traders got on board, doubling prices for occupiers paying in roubles. Into the autumn, as Ukrainian forces approached the city, many residents refused Russia’s orders to evacuate, leaving buses heading to Russia empty. ‘Someone must greet the army!’ said one activist who chose to remain in the city throughout occupation. On 11 November, Ukrainian forces entered the city, rewarding the patience and belief of Kherson’s residents.

Published 19 April 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Krytyka © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.