Since the mass protests in Belarus in 2020, the Lukashenka regime has undergone a totalitarian transformation. Its many instruments of repression serve a single end: to prevent civil society from becoming the driving force of another revolution.

What would you take with you, time permitting, if forced to flee your home? Keepsakes – once sent across distance by migrant family members, documenting key moments of life, and even death – gain new significance when returning is no longer an option.

How can we speak of these ‘common things’, how, rather, can we stalk them,

how can we flush them out, rescue them from the mire in which they remain stuck,

how can we give them a meaning, a tongue,

so that they are at last able to speak of the way things are,

the way we are?

Georges Perec, Approaches to What

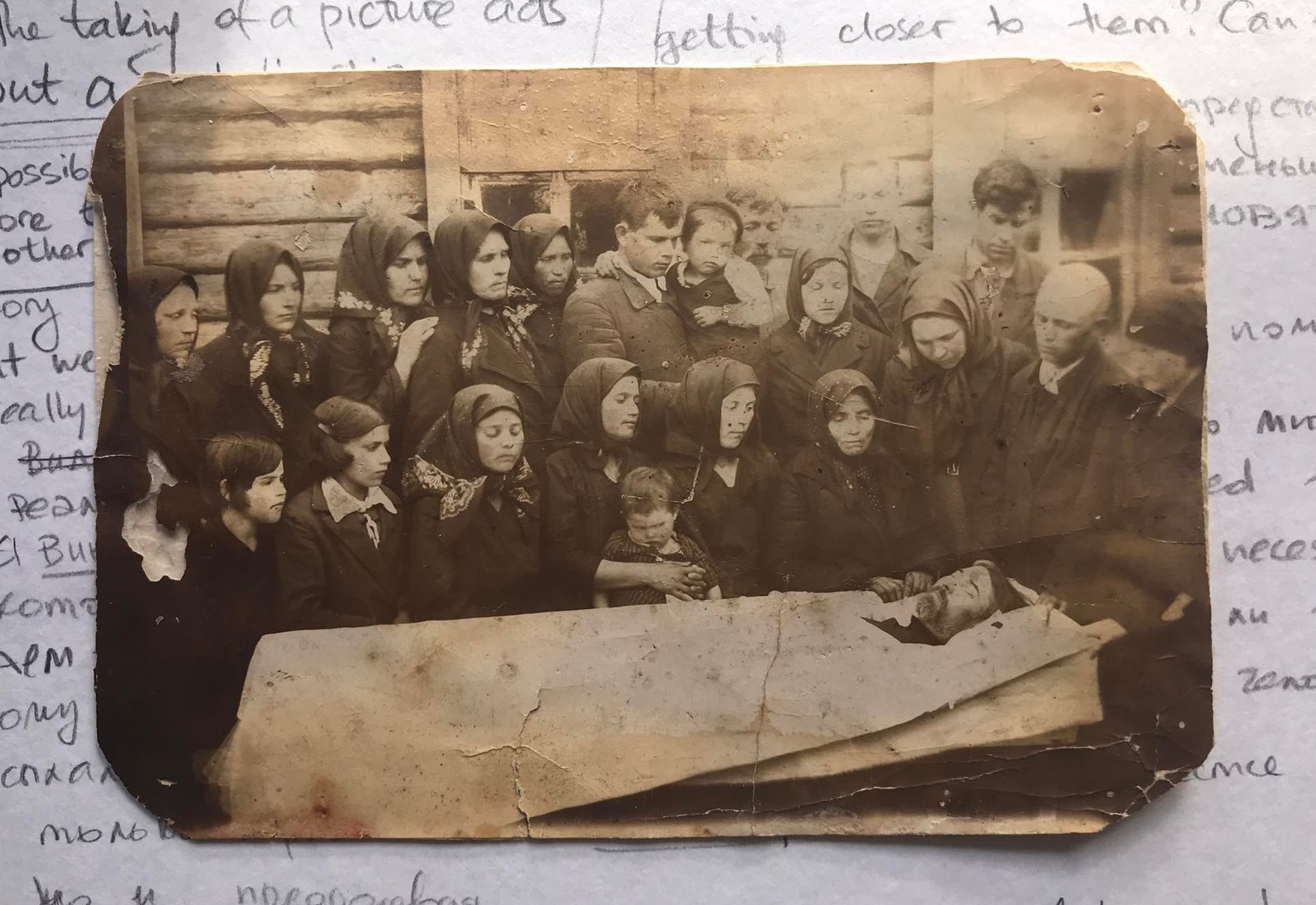

In 2021, I left Belarus not knowing whether I would ever be able to return. Among the items I believed to be among the most precious to keep was a printed image of my great-grandfather, Mitrofan Serebryakov’s funeral, dating back to 1938. Here it is, right in front of me, on my desk, after having travelled across five apartments in two years. From the mist of the sepia, flickering through almost a century of births and deaths, is a handsome, bearded man lying peacefully in an open coffin, who I never knew. The deceased is surrounded by a group of mourners, mostly young and middle-aged women in identical floral-lined headscarves (probably borrowed or purchased specifically for this sad occasion) – all but one also strangers to me. The sole person I recognize is a 14-year-old in something that looks like a rough, oversized man’s jacket – my grandmother to be, Maria.

Image courtesy of author, 2023

Now that I have this extended family by my side, I spend hours scrutinizing their serious faces, simple clothes and reserved gestures. I can reach out to them, touch them. But does it mean I know any of them better? Reflecting on the complicated but still close relations between looking and touching, Margaret Olin might suppose that I do: ‘Touch puts people in contact with photographs; but as photographs pass from hand to hand they establish and maintain relationships between people – or try to.’

From the late seventeenth to early nineteenth century, written and visual communication extended its reach, as migrating relatives sent one another touching ‘touchable’ proof of various kinds: notes, handkerchiefs, locks of hair. And, as Raymond Williams acknowledges, photography then joined this trend, literally helping keep families ‘in touch’ once economic necessity had scattered them across the globe.1 Photographs were precious both because of their high production costs and the milestones they captured: the faces of curious newborns, solemnly dressed newlyweds, the calm ‘newly deceased’. I ask myself who my great-grandfather’s funeral image was meant for. Were there many relatives in faraway lands to send this photo to? Did they eventually get it? Was I also one of the addressees?

My teenage grandmother didn’t suspect that precisely ten years later she would move to another country herself and marry a guy known as the son of ‘the American’. My great-grandfather, Ivan, was famous in his village for having travelled to the US as a migrant worker, and having returned – a decision, which in the Soviet Union, cost him his life. He died in almost the same year. Ivan Kozel was shot in the back of his head by Bolsheviks. He was 54 years old, a father of four.

Ivan never had a post-mortem picture taken of him after death. Neither were his relatives notified. Only a few months ago, did we learn about his actual fate, 86 years after the shooting. All this time, even for his grandchildren – my mother, her sister and brother – he remained a story, one unwillingly shared during family gatherings. In large and small histories of our region’s kin and their countries, silence was a frequent guest. Along with the family jewels, half-demolished village houses and old photos, we inherited suspicion, fear and the invaluable preciousness of touch.

Image courtesy of author, 2023

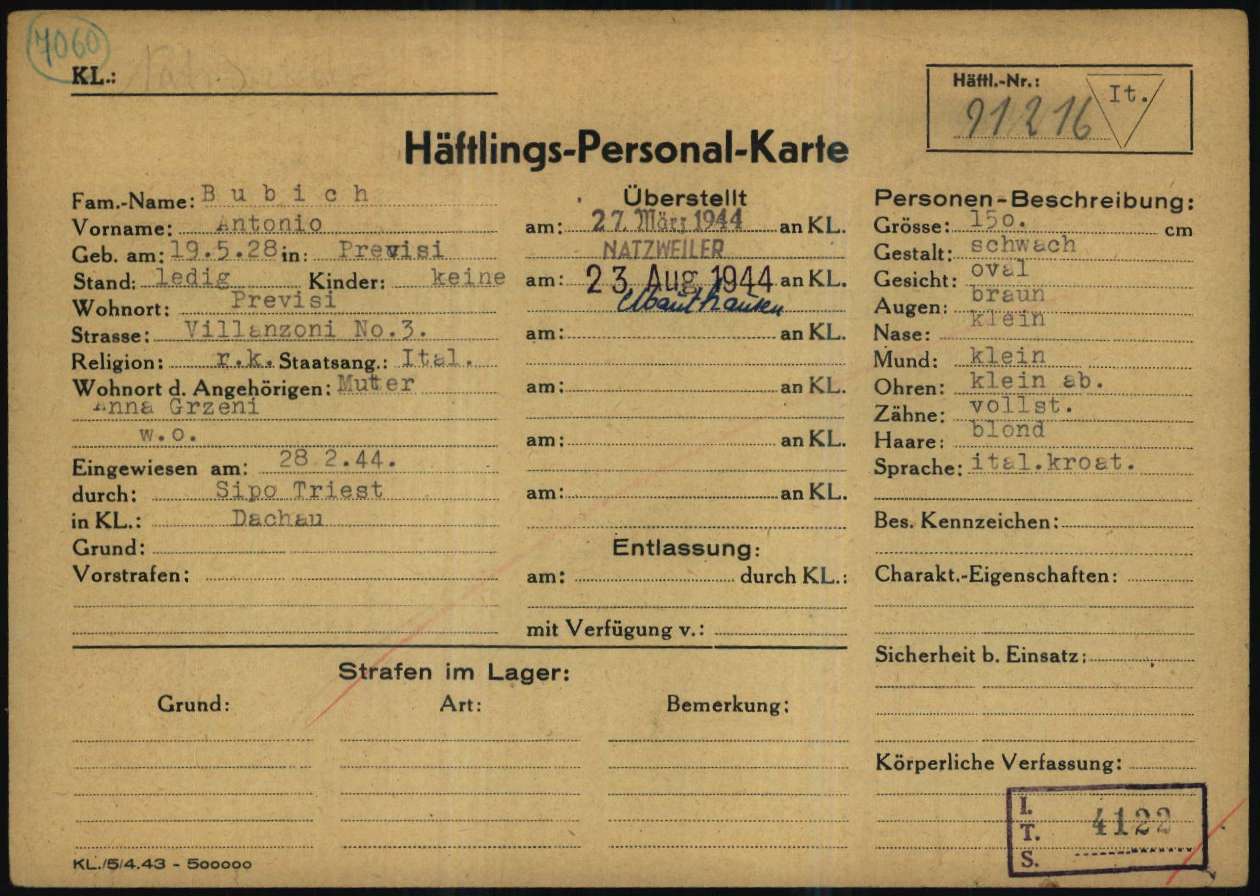

The flickers of visual information I have managed to collect of certain ancestors is due to sheer luck. Others have left only vague silhouettes, undiscernible contours, signs I am struggling to decipher. They lived on in the mementos of those who, in their turn, have also passed a long time ago, at times alerting me to their presence. One such sign is the labor camp registration card of a 16-year-old Antonio Bubich: ‘prisoner number 91216’, whose SS inverted-triangle badge marked him as Italian.

The teenager was born in 1928, a peer of my paternal grandfather, Vasily, who escaped this brutal fate. Our namesake was arrested in February 1944 and, over six months, witnessed three camps: Dachau, Natzweiler and Mauthausen. Meticulous measurements from 28 February to 23 August, made by the camps’ administrations, show that the youngster made a 10 cm leap in height. Blond with brown eyes; state of teeth, ‘satisfactory’; hearing and sight, ‘good’; occupation, ‘learner’ – classification was a routine practice for the Nazis. Deeming the representatives of other nationalities’ as ‘non-Aryan’ – and, therefore, of ‘inferior background’ – they literally treated people as objects in a horrendous catalogue of curiosities, labelled in various degrees of banality.

On prisoners’ arrival in concentration camps, ID photos were taken. Francisco Boix, a Catalan inmate and camp survivor, worked in the Mauthausen camp administration’s photography department. Understanding the critical importance of visual evidence, Boix risked his life to hide and preserve around 2,000 negatives, which would play a significant part in the conviction of Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg and Dachau trials. Perhaps, being around the same age, Boix had befriended the young Bubich. Hopeful of learning more, I filed a request to Mauthausen memorial site archives and received a reply one week later.

‘Dear Ms. Bubich,’ it read, ‘Thank you for your enquiry. Unfortunately, we have to inform you that we do not have any photographs of Antonio Bubich in our archive. The prisoners were indeed photographed and registered upon their arrival at Mauthausen. However, these files were systematically destroyed by the SS shortly before the end of the war. Only about a dozen photographs from Mauthausen have survived.’

I don’t know – and it’s unlikely that anyone can now prove – if Antonio Bubich and I are related. And, as the above email makes clear, neither can I cherish the hope of ‘touching’ him photographically, looking for possible similarities in our appearance, or speculating about his character traits. On 5 May 1945, American soldiers arrived in Gusen and Mauthausen and liberated around 40,000 prisoners. Was Antonio still alive on that day? Was he one of those ragged but free survivors seen cooking potatoes in a German Army helmet? Did he reunite with his family in ‘Previsi’ – the probably misspelt name of his hometown that I failed to locate on a map of North Italy? Did he make it?

Registration card. Image courtesy of author

Without evidence, I will never have answers to these questions. ‘Made possible by context, photographs are more than context,’ writes Olin, ‘they touch one other and the viewer. They substitute people.’ She was right. Photographs do substitute people, but so too does the void. Sometimes, silence can speak – we just need to learn to listen.

One of the best-known documentary art projects aimed at memory preservation is also connected with touch: Stolperstein, the German for ‘stumbling stone’, metaphorically meaning a ‘stumbling block’, refers to the brass plates embedded in paving slabs passers-by are supposed to come across coincidentally and thus pay more attention to. As of December 2019, about 75,000 such blocks with inscribed names and life dates of victims of Nazi extermination or persecution had been installed in more than 1,200 cities around the world. The concept, conceived by German artist Gunter Deming in 1992, might provocatively be connected to the antisemitic phrase, once popular in Nazi Germany, said when accidentally stumbling over a protruding stone: ‘A Jew must be buried here.’

Stolpersteine are not so easy to detect. If huge monuments are designed to impress when spotted from distance, little brass plaques emphasize the ‘smallness’ of human lives and, if you want to learn more about them, you must be humbled and lean down. It is only by the conscious reduction of distance, preceded by the readiness for contact, the desire to get to know someone’s past – your own, even – that one realizes the life of another person can also be large.

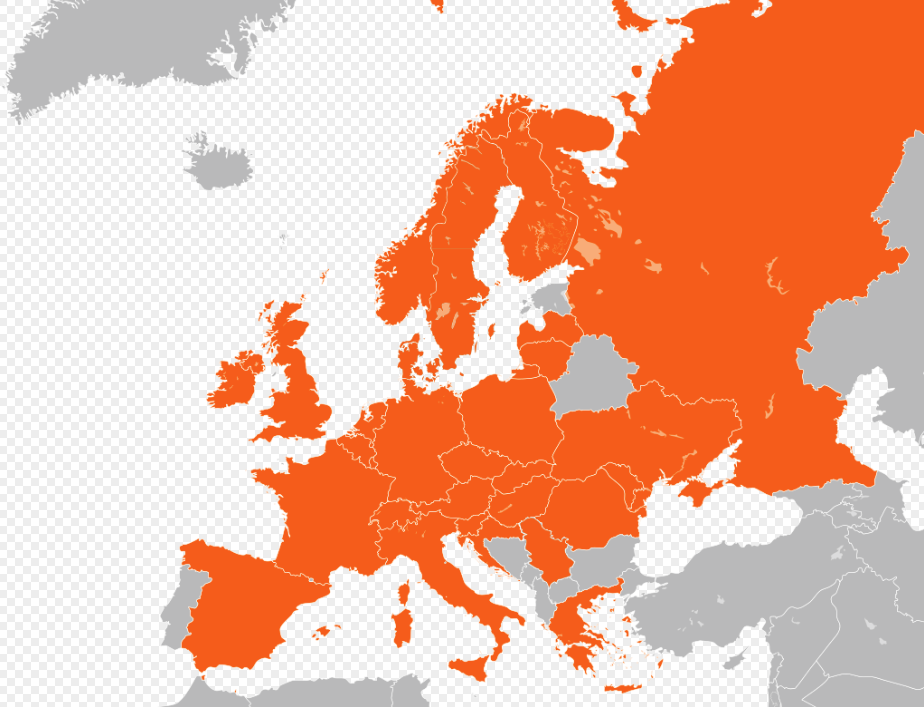

Not every country that has faced mass murders, repression and torture is ready to lean down and put effort into processing trauma. Recognition of guilt should be followed by the next, even more complicated step: acceptance of responsibility. Russia, a state that destroyed more than three million of its own people in its Soviet past, doesn’t want to admit this fact even a century later. A quick glance at the Stolpersteine map helps understand the Kremlin’s amnesia: Russia, though coloured orange, only has two memorial stones installed within its vast area.

The ‘Last Address’ grassroot initiative inspired by Deming’s concept hasn’t caused much enthusiasm among certain state bodies. Memorial plates have ended up being dismantled by local administrations or anonymously vandalized in Russian cities. Police have refused to investigate the cases. Attempts to silence memory can’t be classified as crimes, can they?

Overview of countries where Stolpersteine have been installed.

Cirdan – Own work, based on File:Blank map of Europe 2.svg by User:Nordwestern. Image via Wikipedia

The photo sitting on my desk is a luxury. Apart from my teenage grandmother in the image of my great-grandfather’s funeral, there is one other person I know – myself. I am not ‘there’ but am ‘present’. From my 2023, I can touch their 1938.

I am doing my best to hear the touching memories in the choir of speaking voids.

In association with ICORN, where Olga Bubich is currently a fellow.

R. Williams, Television: Technology and Cultural Form, University Press of New England, [1974], 1992, pp.16-17.

Published 27 March 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Olga Bubich / ICORN / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Since the mass protests in Belarus in 2020, the Lukashenka regime has undergone a totalitarian transformation. Its many instruments of repression serve a single end: to prevent civil society from becoming the driving force of another revolution.

On the border between Poland and Belarus, the Forest has become the subject of a humanitarian crisis. An artist’s report, based on meetings with activists and refugees, charts this contested space. Poetry honours those lost in transit.