If, like Miriam Rasch, you want to resist seamless dataism and de-automate your life, why not take a look at her ‘Tangent’ on the subject. The following recommended reading from the Eurozine archive spans articles from the politics of digitization to poetry’s ability to creatively engage with fragmentation.

Dataism is the belief in digital data’s capacity to provide exhaustive knowledge and control the world. Its pretensions are universalistic and dogmatic; its consequences can be dire and deadly. As citizens and ‘users’, how can we resist constant data capture, categorization and control? A discussion that moves beyond rules and regulations is needed to counter data logic. A different narrative or rather many different narratives can provide alternatives to data’s all-encompassing and seemingly inevitable grasp.

Dataism and its limits opens pluralistic avenues of thinking. It begins with articles that dive into digital technologies and their implications before veering off in different directions: history and language, the concept of truth, and the possibilities of resistance all tell us something about the limits of dataism and why they should be identified.

The politics of artificial intelligence

An interview with Louise Amoore

Louise Amoore and Krystian Woznicki

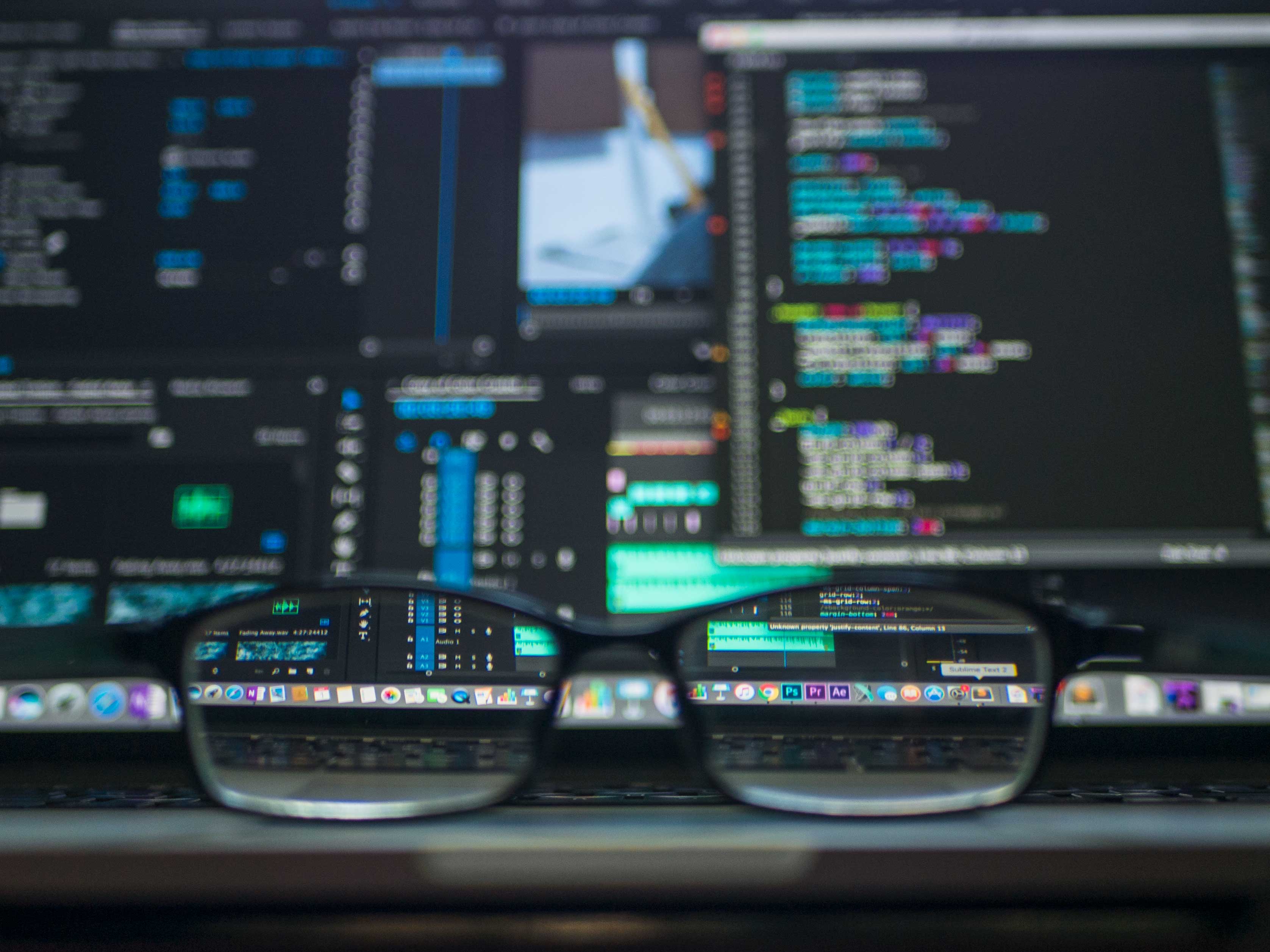

I want to start this list with three essays that were important for my own book Friction: Ethics in times of dataism. The first is an interview with Louise Amoore that very concretely lays out why the use of algorithmic applications can have detrimental effects at, for example, border controls, by flattening out ethical considerations. It is a brilliant example of a philosophical interview on a controversial and urgent topic.

‘To rethink human agency against this backdrop implies an acknowledgement of the composite forms of agency that emerge in our entanglements with algorithms and machines. I think that this should be given greater attention in debates about the ‘human in the loop’ supposed to supply the locus of ethics for composite systems such as autonomous weapons. Who is this human? How are their embodied relations to the world changed through their collaborations with algorithms?’

Photo: Kevin Ku. Source: Pexels

The black box is a state of mind

The second is Kathrin Passig’s exposé on the ‘blackboxification’ of technology that is often invoked to criticize tech platforms. She shows how the binary opposition between mystery and transparency is unhelpful in all respects. Her argument is furthered in one of the chapters of my book, where I suggest we shouldn’t refer back to ‘the ineffable’ when formulating a critique of dataism.

‘Reverse engineering and biology are both fields where researchers investigate complex, non-transparent and non-linear systems. Particularly in biology, demands for better documented and more comprehensible organisms won’t get you very far. Even creatures that are literally transparent won’t make your work much easier.’

Photo source: Quim Gil

Deglobalization

Then there is a Achille Mbembe piece that is fabulous in its argument ranging all the way from digitization to the need for abolition of borders. It shows how digital technology and datafication can’t be seen separately from the political. I was so impressed by this essay that I printed it out for my archive.

‘Every sphere of life has been penetrated by capital and subjected to quantification. In this context, borders have become nothing other than the violence underlying our world’s order, a war against mobility that is filling Europe with dead bodies and migrant camps. Can we dare to imagine the abolition of borders?’

Source: pexels.com

Better living through Bitcoins

A cryptocurrency is the ultimate ‘life-hack’

Another essay that deals with the entanglement of data technology and ideology is ‘Better living through Bitcoins’, which finds a connection between life-hacking and cryptofinance through their mutual libertarianism.

‘If the fantasy of life-hacking is to find a personal, technical solution to life’s troubles, then Bitcoin is the ultimate financial-hack, an individualistic short-cut through the intrusions of government we call regulation and taxation.’

Photo by Zsolt Szigetváry via Fortepan

This mess of troubled times

How do we resist Total Datafication, which aims to control, surveil and exploit us, robbing us of meaning and a sense of autonomy by rendering such notions outdated or even obsolete? The answer, I believe, starts with resisting the dataist logic that only values the determinate, the countable, the unquestionable. One way to do that is by showing what is indeterminate, unmeasurable, and always questionable (which doesn’t mean that it’s ineffable, see above). There are always more narratives to tell, more interpretations to discuss, more translations to make than just the digital translation into zeros and ones. This is something the following essays also explore, starting with the moving and important lecture by Karl Schlögel about the extended history of 1989.

‘Instead, my approach will be personal and biased, full of distrust for generalizations and the certainties that theoretical models and paradigms offer.’

Artwork by Jaume Plensa at The Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Photo by Neil Theasby from Geograph.org.uk

A finger pointing at the moon

To follow, a beautiful meditation on the mess of troubled mother tongues by Olga Tokarczuk, which interests me personally because Polish was always present in my childhood even if I do not understand a word, as my parents met through their study of the language. This is where my interest in translation began.

‘I am embedded in Polish like a fly in amber. It is not an objective point of view.’

Photo by distelAPPArath from Pixabay

On some applications of ‘compressed air’

Reviewing Iestyn Tyne with Irmtraud Morgner

Fragmentation, poetry, reading and the inescapable yet never fully pinned down role of context is evoked beautifully in this essay about Welsh poetry – I just love all these languages coming to me through these essays.

‘We may believe, today, that the best way to read and write is with patience and order. One day, I think, we’ll believe in the opposite, in explosive reading and writing.’

Photo by Michael Carruth on Unsplash

A pre-history of post-truth, East and West

The intricate workings of language show that the dataist, or solutionist, or tech chauvinist way of looking at things always falls short. Language is no miracle worker; otherwise that would mean another one-fits-all-solution. The next two pieces show that zooming in on the political moment of post-truth reveals a phenomenon that not only cannot be grasped without taking digital technology into account but also has its own forbears. The comparison that Marci Shore offers in the first essay between East and West and historical and contemporary post-truths is exemplary for the kind of analyses needed to understand such intricate developments.

‘The end of ‘The End of History’ arrived together with the end of belief in reality. The Cold War world was a world of warring ideologies; in the twenty-first century, both American capitalism and post-Soviet oligarchy employ the same public relations specialists catering to gangsters with political ambitions. As Peter Pomerantsev described in Nothing is True and Everything is Possible, in the Russia of the 2000s, distinguishing between truth and lies became passé. In this world of enlightened, postmodern people, ‘everything is PR’.’

Embassy of Intimacy – Dutch Design Week 2017

Photo by Hanneke Wetzer via Mumu from Flickr

Control groups

An interview with William Davies on politics in an age of sensation

William Davies and Tobias Haberkorn

William Davies is another sharp analyst and commentator of our political moment and the role social media and platform logics play in that – someone whose work I use in my book as well. I could quote all of this interview, so just go ahead and read it.

‘Like any cultural content, politics is increasingly evaluated in real time, in terms of clicks, eyeballs, likes and so on. All of this means that public figures, be they in the media, politics or arts, end up as live performers – a bit like sports stars or stand-up comedians – who achieve credibility through a kind of carefully honed spontaneity. Traditional forms of liberal authority were never designed to achieve such immediate effects on an audience.’

Photo via Pikist

‘Nee! Nee!’

Remembering ultimate acts of resistance

To close, I choose this piece by Arnon Grunberg that caused a stir when he read it on national television on 4 May, the Dutch WWII Remembrance Day. There is a possibility of saying ‘No’ and it may be the strongest word we have to resist. In my book I trail this ‘No’ as well, as it is one of those words that opposes all that dataism, with its confirmations and presentisms, stands for. ‘No’ is also a democratic and accessible weapon, as Grunberg reminds us, even if used to no avail.

‘“I can’t understand, cannot tolerate it when a person judges another person not by what he is, but by the group to which he happens to belong”, Primo Levi wrote to his German translator in the 1960s.’

Published 14 October 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Miriam Rasch / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Growing reluctance to engage with books is endangering democracy and science. Deep reading boosts the human capacity for abstract and analytical thinking, protecting us from the corrosive effects of bias, prejudice and conspiracy theories.

The digital world we navigate today was built on centuries of technological innovation by librarians and archivists. The unprecedented access to online information now compels these institutions to evolve. In this discussion, librarians and a data steward from Helsinki, Vienna, and Pécs explore the challenges and opportunities of this transformation.