On 29 March, hundreds of thousands gathered at Istanbul’s Maltepe beach area – some even say it was 2.2 million. Waving flags and chanting slogans, the protestors demanded the release of Ekrem İmamoğlu, the mayor of Istanbul who had been detained the week before. On 23 March, İmamoğlu and 47 others were arrested on corruption charges; that same day, the People’s Republican Party (CHP) announced İmamoğlu as its candidate for Turkey’s 2028 presidential elections, after holding a symbolic ballot.

On the day of the rally I was writing in my studio, four kilometres away. The sound of the crowd floated through the air, rising and falling in waves; the songs, chants and slogans seemed to be coming from many directions. Even after closing the window, I could hear the tenor of the speeches: the angry, joyful, despairing voices of İmamoğlu’s wife, of his mother, and of Özgür Özel, the CHP leader. The rally felt like a natural phenomenon, a snowstorm or a tornado that surrounded my reality in Istanbul.

I gave up trying to write and turned on the TV.

A cookery show. A program about the approaching Eid al-Fitr. Footage from the devastating earthquake in Myanmar. The weather. A Coca-Cola commercial. Sports commentary about that night’s match. A documentary on global warming. The producers of Turkey’s leading news channels were obviously the only ones in the country who hadn’t heard about the İmamoğlu rally.

For the rest of the day, and in the papers the next morning, Turkey’s government-controlled media avoided any mention of the demonstration. The media silence seemed unsustainable. But it was sustained and – as I write these lines – still is.

No wonder that Turkish culture is becoming increasingly Soviet in outlook. The gap between what you see on the street and what you get in the media is widening all the time. When I spend time in Istanbul, the city where I was born 44 years ago, I often feel compelled to distrust my eyes, ears and heart. Because what I see, hear, and think has become too dangerous to acknowledge.

At times like this, I have a dark urge to ask the system to control my mind. What exactly am I supposed to say and think? It seems the government requires from its citizens a composite of despair, apathy and numbness. But that’s a difficult feeling to manage on one’s own.

*

I ended up watching the speeches on the YouTube channel of Sözcü, an opposition TV station. (The next week the government announced it would shut down Sözcü because of its wall-to-wall coverage of the protests.) And then something unexpected happened.

It was at 2.53 p.m. when Özel – an uncharismatic but highly effective party leader – asked the crowd whether they knew which TV channels were showing the rally and which were not.

One of the ones not showing it was NTV, once a darling of progressives that had run programming in the mould of MSNBC, its US sister channel until 2014. If NTV hadn’t reported on the rally by the top of the hour, he would issue a boycott, Özel warned.

I tried to imagine the scenes in the newsroom. Editors and producers pondering whether to go live. Whether to cover the rally negatively, perhaps as an illegal gathering. Or to simply ignore it. There was a brief will they or won’t they moment. Minutes passed. Not surprisingly, the channel chose to ignore the rally entirely.

As the media boycott reality, people are boycotting the media. Özel reeled off a list of further newspapers and TV channels that supporters of the CHP would boycott. He would remove the boycott once the media changed their mind and started covering events.

*

In autocracies, individuals are forced to lead two different, interweaving lives. In private, they talk and act in one way; in public, they speak and behave in another. The rift is soon normalized. To the eye of the silenced citizen, it appears to be the foundation of public life. The rift’s widening signals an authoritarianism on the rise.

When I covered the Gezi Park protests in 2013, I noticed how the crux of what activists were articulating was a refusal of this separation between the public and the private. The millions who flocked to that small park in Istanbul were objecting to life in the closet of normativity, at a moment when Turkey’s hybridity seemed to be blossoming.

At the time I was struggling with a new novel. Increasingly, I had found myself unable to write in what I considered the ‘artificial’ mode of fiction. The reality surrounding me was much more interesting. Making up plots, characters, patterns and conflicts, as one would for, say, a historical novel, seemed unbearably suffocating, even a betrayal of the act of writing.

Developments in Turkey were a wake-up call, a reminder of cold realities of the country. They also gave us a chance to explore and understand ourselves, our passions and red lines. For years, the media had gone along with a narrative fabricated by the government. Then, suddenly, young people challenged it with their own realities. This was what I wanted to do in my writing, too. All I could rely was on my own experience and observations. Since Occupy Gezi Park, I began to write autofictions.

The protests, which continued for 18 days, dismantled the myth of the ‘New Turkey’, just one of many externally imposed fictions. Nobody with eyes and ears could still believe that the country was undergoing a process of democratization. At the beginning, liberals had considered support for the government from the most deprived sectors of society as a mark of its democratic credentials; but now that support was in freefall. The Gezi protesters showed how selfishness, profit and disregard for the suffering of others had come to define Turkey’s regime.

The intervening years have brought a relentless assault on queer communities and other marginalized groups, as the government has sought to consolidate normativity. Ecocidal acts carved out space for airports and other construction projects. And then there is the sneering cynicism towards anyone interested in leading an ethical life.

During the latest protests, I have been reminded of a remark by Franz Kafka: ‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.’ For many of us, Gezi was that axe, which fell on what Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky called ‘manufactured consent’. No wonder that Turkey’s government-controlled media is refusing to let that axe fall again.

*

İmamoğlu’s arrest prompted a series of op-eds in the international press. Was Turkey still ‘competitive authoritarian’, or had it sunk further down the democracy scale?

While the conflict is clearly between the forces of democracy and autocracy, it isn’t immediately clear that an electoral victory for the democrats would pacify the country. That, I think, requires a more comprehensive reckoning with the cultural texture that has emerged in the past two-and-a-half decades. Nobody should underestimate how ‘New Turkey’ propaganda has shaped minds and behaviour. Unlearning selfishness and apathy takes time.

Alongside the symbolic primary election organized by the CHP, which 15 million people voted in, the party launched a petition for İmamoğlu’s release. ‘I am one of the tens of millions of patriots whose hearts beat for the Republic, democracy and justice,’ it reads. ‘I am signing this to see my candidate next to me and the ballot box in front of me.’

The petition is the latest attempt to crush a culture of concealment and silence. As a method of dissent, it has swiftly dispersed among networks whose members feel similarly about the mayor’s arrest. But the government has a more diverse selection of tools and tactics in its arsenal.

Soon after the CHP launched Boykotyap.com, listing the brands it was boycotting, the government shut the website down. The CHP changed the URL to Boykotyap.net. When the government blocked that a few days later, the CHP launched Boykotyap.org. But that can disappear too, if and when the government decides.

On 1 April the public prosecutor’s office in Istanbul opened investigations into the boycotters on the grounds of incitement to ‘hatred, discrimination and hostility’, with the interior minister describing the calls for boycotts as a ‘coup attempt’. The following morning, the police detained 16 suspects, including the actor Cem Yigit Uzumoglu, who played Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror in the Netflix series ‘Rise of Empires: Ottoman’. Scores of actors and scriptwriters had their contracts with the national public broadcaster TRT revoked after voicing support for İmamoğlu. Their films and TV shows were also excised from TRT’s digital library.

The game of whack-a-mole can continue as long as both sides want and is sure to test their patience. In material terms, the government has the upper hand: the next elections are in three years, and it says there is enough money in the state coffers to avert a financial meltdown. In the week after İmamoğlu’s arrest, the Turkish Central Bank spent almost $12 billion in foreign reserves to prop up the lira after it hit a record low of more than 40 to the dollar. There is still an estimated $150 billion that the government can use in case of more socio-economic turbulence. Despite grumblings from the US State Department and the European Council, the western response to the arrest has had the strength of chamomile tea.

The government knows it has extensive room for manoeuvre. Shortly after İmamoğlu’s arrest, it announced that Eid al-Fitr, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, would last nine days, one of the longest in recent history. This was calculated to be a sedative: closing schools, businesses and public offices would limit the effect of sociability and discourage public displays of dissent.

In response, activists have been flexing their muscles on social media, naming and shaming businesses whose leaders have insulted İmamoğlu and his family. Among those targeted was a public events producer, prompting the South African comedian Trevor Noah, the Norwegian singer-songwriter Ane Brun, and the British rock band Muse to cancel their Istanbul dates.

To avoid the impression of weakness, the government needs to stay on the offensive. Censorship is its go-to solution. During Eid al-Fitr, pro-government lawyers petitioned courts to shut down İmamoğlu’s social media. The mayor’s allies have been using his X account, which has 9.7 million followers, to disseminate calls for rallies. If this fails, the government can throttle entire platforms, as it did after the earthquakes in 2023. Ankara used this tactic again after İmamoğlu’s detention, when for three days YouTube, WhatsApp, and Instagram experienced slowdowns to the point of inaccessibility.

*

Istanbulites have displayed their trust in the mayor by voting for him three times in five years. With electoral margins like this, no wonder İmamoğlu unsettles officials in Ankara. He reminds them of the government’s diminishing popularity. The CHP won 35 out of 81 municipalities in the local elections just a year ago, including mayoral victories in Turkey’s five largest cities: Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Bursa and Antalya.

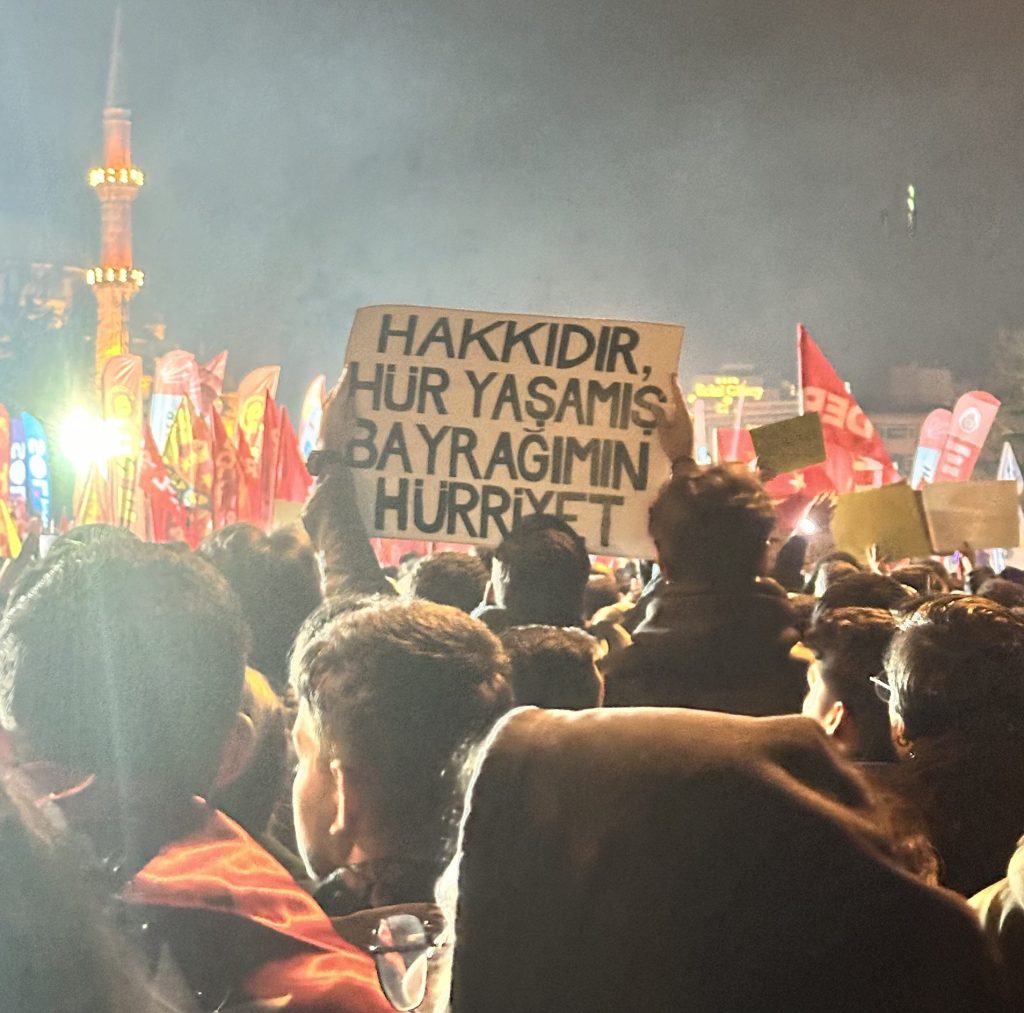

But with no elections scheduled until 2028, polls matter less than naked force. Besides, percentages and statistics cannot describe what has been happening in Istanbul and other urban centres over the past weeks. Walking through the Maltepe beach event area the other day, I felt aware of its immensity. I was so small compared to the space’s peninsula-like dimensions. It was like being in the desert, where nobody can hear you except those nearby.

That my voice could carry for kilometres from here was an exciting possibility, one denied to so many in the country. In breaking the silence that has become engrained in Turkish culture, the people who came here last week to shout for freedom have done a great service to our country.