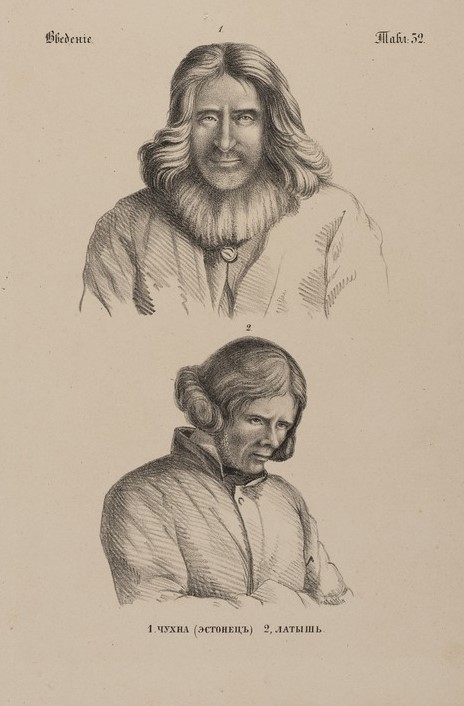

Sometime around 1851, an Estonian man assumed animal form. Despite having pronounced brow bones and an aquiline nose, his long locks and elegant flowing beard verged on the leonine. Rather than capturing a sense of strength and fortitude, these features transmogrified human hair into animal fur, frustrating the visual boundaries between species. Beneath this Estonian figure is a man posed at a quarter profile, bowing his head. Labeled ‘Latvian’, the second figure’s face has a neatly trimmed beard and straightened hair besides the curled tendrils that rest at his ears. The juxtaposition of these two figures reveals distinct physiognomies: the Latvian’s face is circular; the Estonian’s, oval. The frontal position of the Estonian amplifies his visual breadth. He seems more assertive; the Latvian, smaller and withdrawn.

Comparison between peoples – and species – was central to the visual layout of Julian Simashko’s encyclopedic Russian Fauna, or Description and Depiction of Animals Occurring in the Russian Empire, where these illustrations appeared. The scientific framing of these illustrations lent an authoritative aura to his assumptions.

A nervous chuckle arose from the crowd when curators Linda Kaljundi and Kadi Polli informed their audience that Simashko’s image was part of an imperial catalogue of animals. At their curatorial tour of the exhibition, ‘The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus’, Kaljundi and Polli said they were surprised by the discovery of this illustration in their research, the punchline being that the Estonian could be a colonial category of fauna. The encounter with the Estonian-as-animal was so awkwardly humorous because of the precarity of the category of whiteness, which did not include Estonians when this illustration was published in 1851.

Though the Simashko image prompted uncomfortable laughter among some twenty-first century viewers, it invited critical reflection and contemplation among others. When Urmas and Liisa Hõbepappel saw this illustration, it prompted a shift in what they perceived as ‘the schizophrenic self-image of Estonians’. Their encounter with the image unexpectedly provoked ‘a choice between being the viewer or the viewed at the exhibition. Until that point, we had thought of ourselves as citizens of the western world, but in the narrative context of colonialism, we can just as well consider ourselves to be indigenous.’

Race has long eluded Baltic scholars as a category of cultural analysis. References too often describe peoples and cultures being merely ‘exotic’ without any further consideration or critical reflection. The era between 1850–1950 saw the apogee of racial thinking in nationalism, colonialism and, most infamously, eugenics. This period also witnessed the transformation of the racial classification of Estonians from ‘Mongoloid’ into ‘Nordic’, or from ‘Asiatic’ into ‘European’. It is no coincidence that this change overlapped with the political autonomy of the new nation state after World War I. That a nineteenth-century scientific illustration could elicit such ambivalence today raises an important, yet unanswered, question: when, exactly, did images begin to portray Estonians as ‘white’?

It is easier to understand how whiteness assumes pictorial form if we think of the genealogy of racial imagery on a more global scale. Aníbal Quijano and Walter Mignolo famously argued that the concept of race emerged in the sixteenth century as a tool to codify inequalities between Amerindians, Africans and Europeans in the Spanish Americas. It is no surprise that colonial Latin America also produced one of the most explicit types of racial imagery: casta paintings. These images functioned as a visual grid of single-family units, with each image exemplifying a different possible mixed-race offspring. Organized hierarchically by a child’s proximity to whiteness, casta paintings were paradoxical. On one hand, they were visual manifestations of complicated and conflicting ideas of race and power in Latin America. On the other hand, each image required text for distinguishing the specific racial type of each child (mestizo, mulato, lobo, albarazado), revealing that visuality alone was not sufficient to account for a byzantine system of inherited social status. Thus, ambiguity prevailed even in attempts to tie markers of visual difference (‘race’) to concrete ideas.

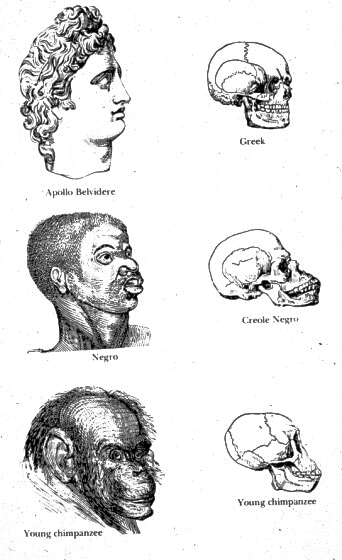

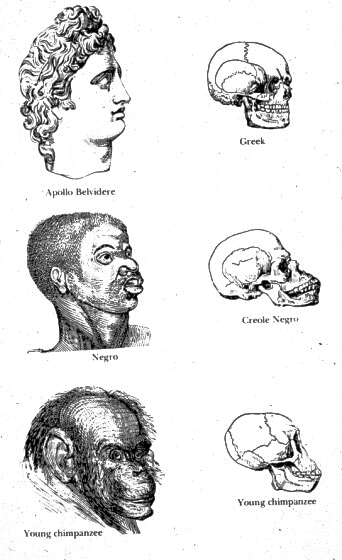

The persistence of these contradictions encouraged the development of fields like phrenology – the measurement of skull shapes as an index of intelligence – whose sole function was to naturalise and reinforce existing hierarchies of power. One of the most nefarious visualisations of this agenda juxtaposed the skulls of a ‘Greek’ and a ‘Creole Negro’ with a ‘Young chimpanzee’. The visual valences of this kind of pseudo-scientific racism may speak for themselves, but it bears mentioning that the example of whiteness comes from the marble head of the first-century Roman statue of Apollo Belvedere. This establishes racial and chromatic whiteness as the pinnacle of aesthetic beauty. There are parallels, meanwhile, between the racist suggestion that black people have simian qualities and the contemporaneous rendering of the Estonian figure in Simashko’s catalogue.

Published in Josiah Clark Nott, Types of Mankind, 1854. Public Domain

If scientific illustrations claim to represent truth, photography (invented circa 1840) would radically change the parameters of who was able to visualise it. Innovations in photography’s chemical laws, as well as lighting and exposure techniques, made the medium ever cheaper and more accessible. The Baltic German artist and journalist Leopold von Pezold once remarked that ‘Millions of [cameras] are deployed around the globe, and there is hardly anyone living in a cultured country on whom this apparatus did not carry out its work.’ Nevertheless, the way in which the camera ‘carried out its work’ did not always live up to its democratising potential and often veered towards more exploitative ends of knowledge production. Historian of photography Tõnis Liibek has argued that the Baltic German photographer Charles Borchardt was among the first to deploy the camera ‘directly with the aims of ethnographic documentation’ of Estonian peasants.

Consider an 1867 photograph of Mari Weinberg taken by Borchardt in his Tallinn studio. Draped in layers of multicoloured striped cloth, Weinberg’s body disappears under her clothing; only her face and right hand are visible. She avoids our gaze, instead staring stoically beyond the realm of the photograph, whose oval dimensions reinforce her conical shape, as her bonnet makes up a triangular composition. These compositional elements specifically emphasise the distinctive patterns of the costume, her physiognomy, and her status as a mother. Indeed, a small child sits on the woman’s lap. His piercing eyes gaze directly at the viewer, his tiny leather pastlad (peasant shoes) dangling from a striped day gown. Tendrils of blonde hair frame his chubby cheeks as they escape the furry bonnet fit snugly onto his head. Almost completely covered with cloth, the baby’s phenotype may seem hard to decipher, but the visible details – eyes, hair, skin tone, facial shape – resonate with us because we confront them directly. Underneath the image reads a German inscription clarifying her age and origins: ‘Mari Weinberg, thirty-eight years old, Jüri Parish’. This is important information, since her image was exhibited in an award-winning group of ‘photographic portraits of the most pronounced specimens of the various races’ of the Russian empire at the 1867 Moscow Ethnographic Exhibition.

This was the first exhibition of its kind to take place in the Russian empire. A child of the so-called ‘Age of Exhibitions’ inaugurated by London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, the Moscow Ethnographic Exhibition was, in the words of Nathaniel Knight, ‘a graphic display of the ineffaceable diversity of the Empire’. As Galina Krivosheina has explained, the exhibition’s main triumph was in championing anthropology as a serious science to improve the empire. Framed as a scientific specimen, Mari is no longer an individual but a generic racial ‘type’; her high cheekbones and dark brown eyes function as visual markers of her ethnic origin. European racial theory once classified Estonians as belonging to the Mongolic group, which German scientist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach had described in 1795 as being ‘of a wheaten yellow, with scanty, straight black hair’ and with ‘flat faces with laterally projecting cheekbones and narrowly slit eyelids.’ Although nineteenth century Baltic scholars began to reject the ‘Asiatic hypothesis’, the English publication of Blumenbach’s study in 1865 propelled the Mongolian theory to new audiences, as if to renew its relevance. By emphasising the appearance of Mari Weinberg’s face, her most ‘Mongoloid’ feature, Borchardt visually activated this pseudoscientific discourse of inequality.

At stake in these racial debates was the relationship of Estonians to ‘civilization’, whose most conspicuous marker was clothing. Take, for instance, the comments of a Baltic German visitor to the Moscow Ethnographic Exhibition:

The first encounter consists of photographs by [Louis] Höflinger in Tartu in three large frames, which give us much to think about. What does it mean that an Estonian in Tartu carries a large book and a very mischievous face? That an Estonian coachman in Tartu is dressed in velvet and his dog is carrying a cloth?

This juxtaposition shows how sartorial distinctions threaten the colonial order of Baltic German dominance and Estonian subservience. The middle-class suit and tie was so connected with Baltic German identity that Johann Voldemar Jannsen even declared ‘Estonian! Let you remain Estonian in any clothing and under any name, then you are an honourable man before your people’. Inscribed beneath a portrait of Jannsen in a respectable suit, the text made his self-fashioning seem inspirational, even rebellious. The suit eradicated ethnic difference by severing the connection between the individual and a possible peasant background, making it invisible. By demonstrating that the Estonian could be socially mobile, Jannsen framed himself through a politics of respectability and civilisation. The cultural politics of the nineteenth century National Awakening, of which this is but one example, cleared the path for the admitting Estonians into whiteness.

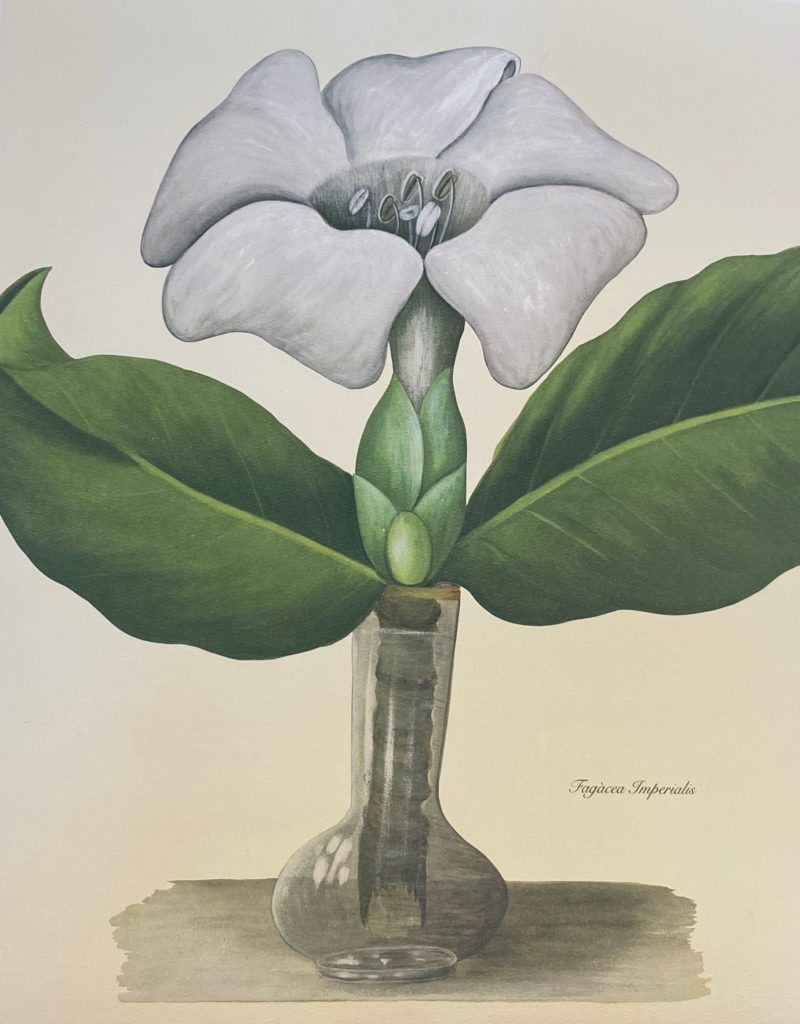

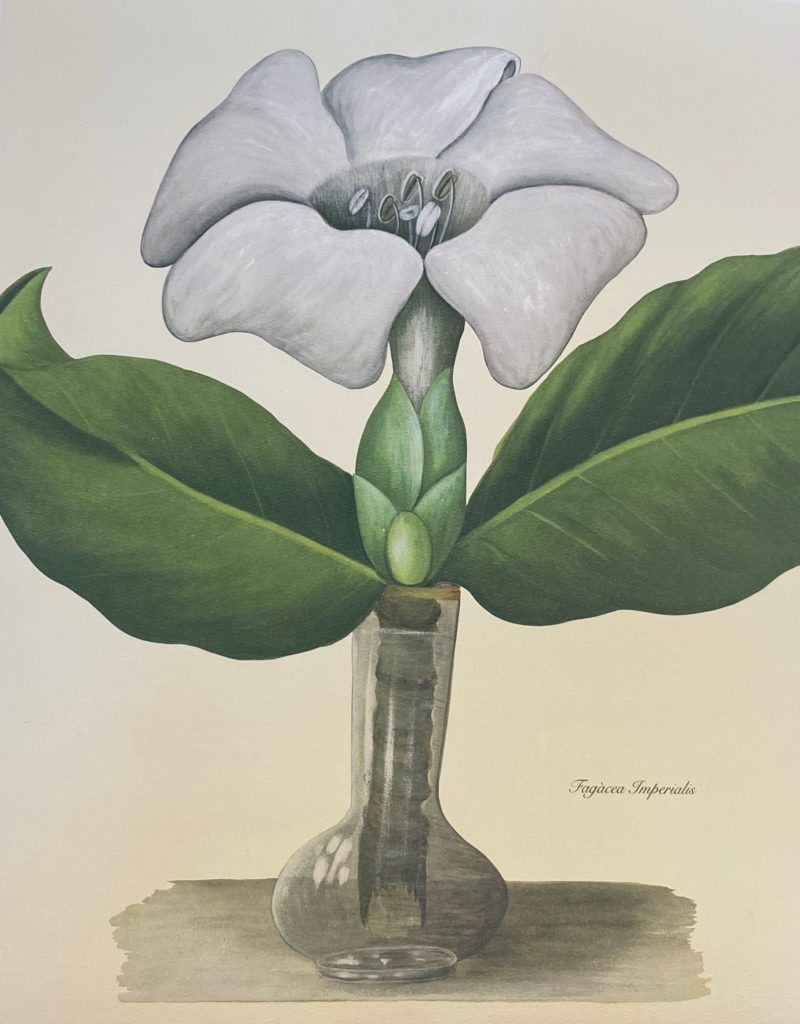

Whiteness also extended beyond the realm of human. Consider a watercolour painting (circa 1910) by Emilie Rosalie Saal. Thick green leaves burst from the slender opening of glass vase, breaching the edge of the picture plane. Flat white petals part to reveal a shadowy black interior, where white pistils yearn for pollinators that will never come. At the bulbous base of the vase, we see where the stalk has snapped, revealing tender interior fibres, a visual remnant of the force deployed to control the site of ephemeral blooms. Cutting flowers and placing them in a vase seems so banal that it might be considered extreme to see violence in it. There is, however, a clear tension in this watercolour: the petals and leaves appear much too large for the glass vase, as if nature itself refuses to be contained by a constrictive human-made compartment.

Emilie Saal, Fagacea Imperialis, ca. 1910-1920. Private Collection. Reproduced

with permission.

As the creative team of Corina Apostol, Kristina Norman, and Bita Razavi will make clear in the 2022 Venice Biennale’s Estonian Pavilion, Emilie Saal created a corpus of some three hundred tropical botanical illustrations when she lived in Indonesia in the early twentieth century. A photograph of the family in Batavia grants us insight into their living conditions. Seated in a spacious veranda, references to ancient Greco-Roman heritage – the same as Apollo Belvedere – abound in this tropical space, from the supporting columns on the left, to the neoclassical sculptures flanking doorways on the right. The aspirational whiteness of the nineteenth century Estonian intelligentsia has, by the early twentieth century, become fully realised. As such, Norman rightly states that, ‘[Saal] was able to emancipate as a woman at the expense of the labour of indigenous Indonesian women who took care of her children and her household and secured her the spare time to dedicate to the science of botany and painting’. This Indonesian labour is absent not merely from the family photograph, but from the painting itself, where the blank white space of the illustration erases the flower’s geographical origins. The oversized stalk stuffed into a small vase calls attention to, rather than concealing, what art historian Daniela Bleichmar has called ‘the extractive vision of global nature’. Note how Saal even painted the reflective surfaces of the glass. Her deceptively simple painting of a flower in fact makes the violence of whiteness visible.

Saal’s newfound whiteness in colonial south east Asia seemed to anticipate the new kind of cosmopolitanism many Estonians would enjoy in the early years of the interwar republic. As Estonians achieved their greatest levels of affluence in their history, experiences with the wider world became increasingly common, and Estonian whiteness ever more familiar. As Jim Crow encouraged African Americans to flee the United States, interwar Europe became an important area of a new black cosmopolitan culture, in which black colonial subjects from Africa, the Caribbean, and the Americas played a foundational role. As blackness gained hypervisibility in popular culture, its expression became strictly regulated across Europe’s national borders. In 1933, Estonia became one of the few countries to ban entertainer Josephine Baker from entering the country, cancelling scheduled performances in Tallinn and Tartu.

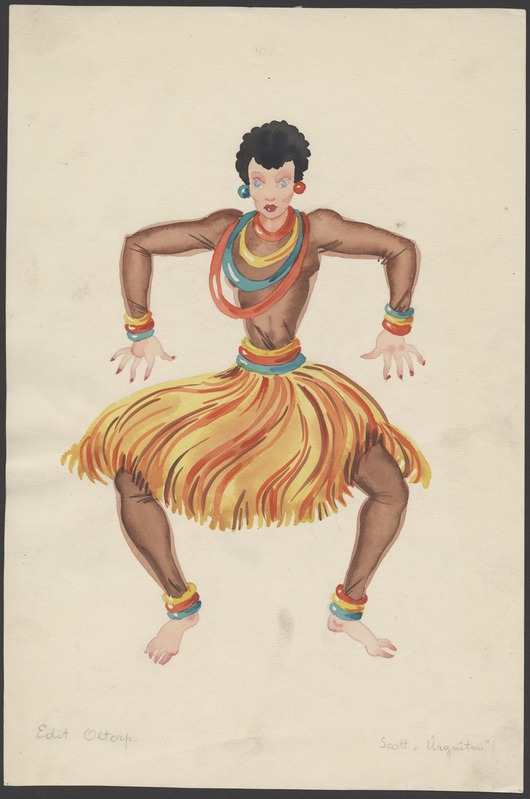

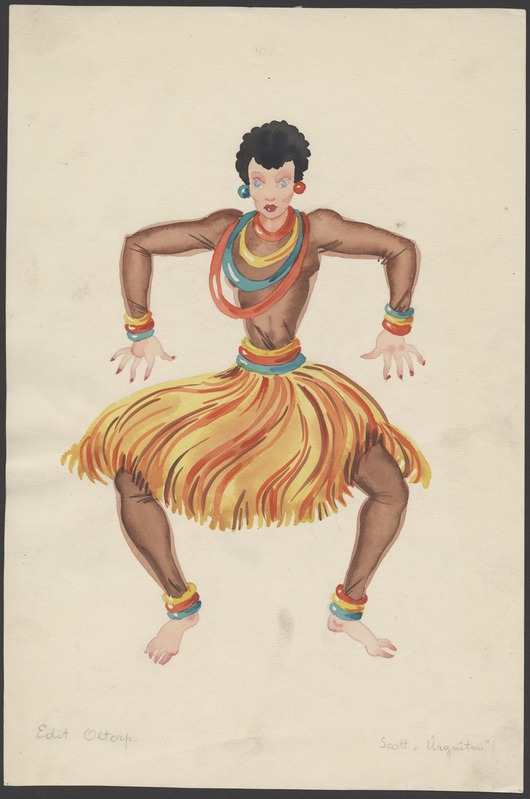

Excluding individual black performers did not, however, prevent the Estonian performance of blackness in the 1930s. Natalie Mei’s costume design for the dancer Edith Oltorp is perhaps the most explicit pictorial example of Estonian blackface known to us today. Painting Oltorp at a wide stance with arms turned at sharp ninety-degree angles, Mei looked to the erratic moves typical of modernist choreography for her design. A rejection of refined European ballet tradition, interwar modernist dance satirised African masquerade (among other traditions), transforming sacred ritual dances into mocking performances of atavism.

Natalie Mei, Ürgrütm Costume Design for Edith Oltorp, 1930s. Estonian Theatre and Music Museum.

This trendy rejection of the European is, of course, above all a matter of costume, from the dancer’s curly black wig, her ill-fitted brown-coloured body suit, multicoloured bangles at her wrists and ankles, and the flowing grass skirt billowing from her cinched waist. That Oltorp appears barefoot and bare breasted further reinforced racialised stereotypes of black savagery to her Estonian audience. Through Oltorp’s performance and Mei’s illustration, blackness is always ephemeral to the white Estonian. Even as a conduit of culture, blackness is removable, making way for the return to whiteness.

The deliberate attempt to keep blackness out was also down to fears about miscegenation. In 1922 Sweden legitimised eugenics as an official, state-funded science, founding the world’s first Racial Biology Institute. Under these premises, a small state like Estonia became ‘ethnically vulnerable’. It is important to recall here that, while the politics of the early republic may have been ethnically inclusive, this did not necessarily extend to matters of race. Since longstanding patriarchal views cast women as the biological custodians of the nation, miscegenation emerged as a threat to Estonian racial purity and the future of the Estonian rahvas. Therefore, it became paramount to visualise virility as something desirably, distinctively white.

Although interwar Estonian art is full of examples of interracial desire, it is equally important to consider the relevance of race in more quotidian imagery. August Roosileht’s watercolour Double Portrait is one example. A stylish young woman from the city has stopped her car on a village road. She holds a basket of vegetables, perhaps cucumbers, as she sits down next to a stonebreaker. In the summer heat, the man has taken off his shirt, revealing a muscular physique after many hours of thankless, back-breaking labour. The pinkish tone of his skin inscribes his social status – rural working class – onto his body. The young woman’s skin is, correspondingly, pale, suggesting not only that she has never done any outdoor labour, but that she has a higher social status. In this flirtatious meeting of city and country, desire does not break the taboos of race, but it does cross class distinctions.

Despite her chic bob haircut, distinctive headband, and fashionable printed summer dress, it is remarkable that the modern New Woman is not sexualised. Patriarchal society had long considered the New Woman lascivious, mostly because of her scandalously short dresses and skirts that reveal bare legs. It is, therefore, important to realize that Roosileht has purposefully hidden such features of his New Woman from our gaze in order to redirect our attention to the man’s sexual attributes. Roosileht’s stonebreaker firmly grasps the wooden handle of his hammer, a phallic sign of virility. His muscular thighs appear so bulky that they burst out of his shorts. In fact, closer inspection suggests that he may not be wearing shorts at all, having instead draped a tan cloth around his genitalia. If the stonebreaker has a firm grip of his hammer, he also appears sensual, with a coy softness to his demeanour as he turns his head towards the woman.

A native of the small city of Paide, some 90km from Tallinn, Roosileht spent much of his career as a professional artist in Järvamaa, distanced from the ‘degenerate’ urban culture of the capital. His eroticisation of this countryside labourer therefore deliberately elevates the young, blonde Estonian man from the rural heartland as the ideal object of desire. His continuous labour in the hearth makes him a healthy, attractive partner. In fact, the visual dominance of the sexualised country worker over the posh urbanite may, indeed, celebrate the vitality of the countryside, rendered here as a nondescript, flat landscape with a body of water. Although we have imprecise dating for this watercolour (anywhere between 1920 and 1941), it is no coincidence that Roosileht’s image was contemporary to the country’s agro-nationalist ideology, promoting racial and ethnic homogeneity within heterosexual pairings to maintain the racial hygiene of the nation.

Roosileht’s muscular white Estonian man also anticipates the shirtless men who populate Jaanus Samma’s 2010 homoerotic photographic series AAFAGC, Applied Arts for a Gay Club (Tarbekunst geiklubile). In the interim, Touko Laaksonen (Tom of Finland) made clear the visual correspondences between masculine homoeroticism and the racialised authoritarian aesthetics of interwar body culture; one need only take a glance to realise a certain correspondence here, since Roosileht’s buff blond also wears boots. But the Soviet Union would deploy Estonian whiteness to new ends, espousing ‘global solidarity’ instead of racial superiority. If the Estonian could be a scientific specimen in 1850, by 1950 she could be a scientist. It was through this tremendous social mobility that Estonians became white.