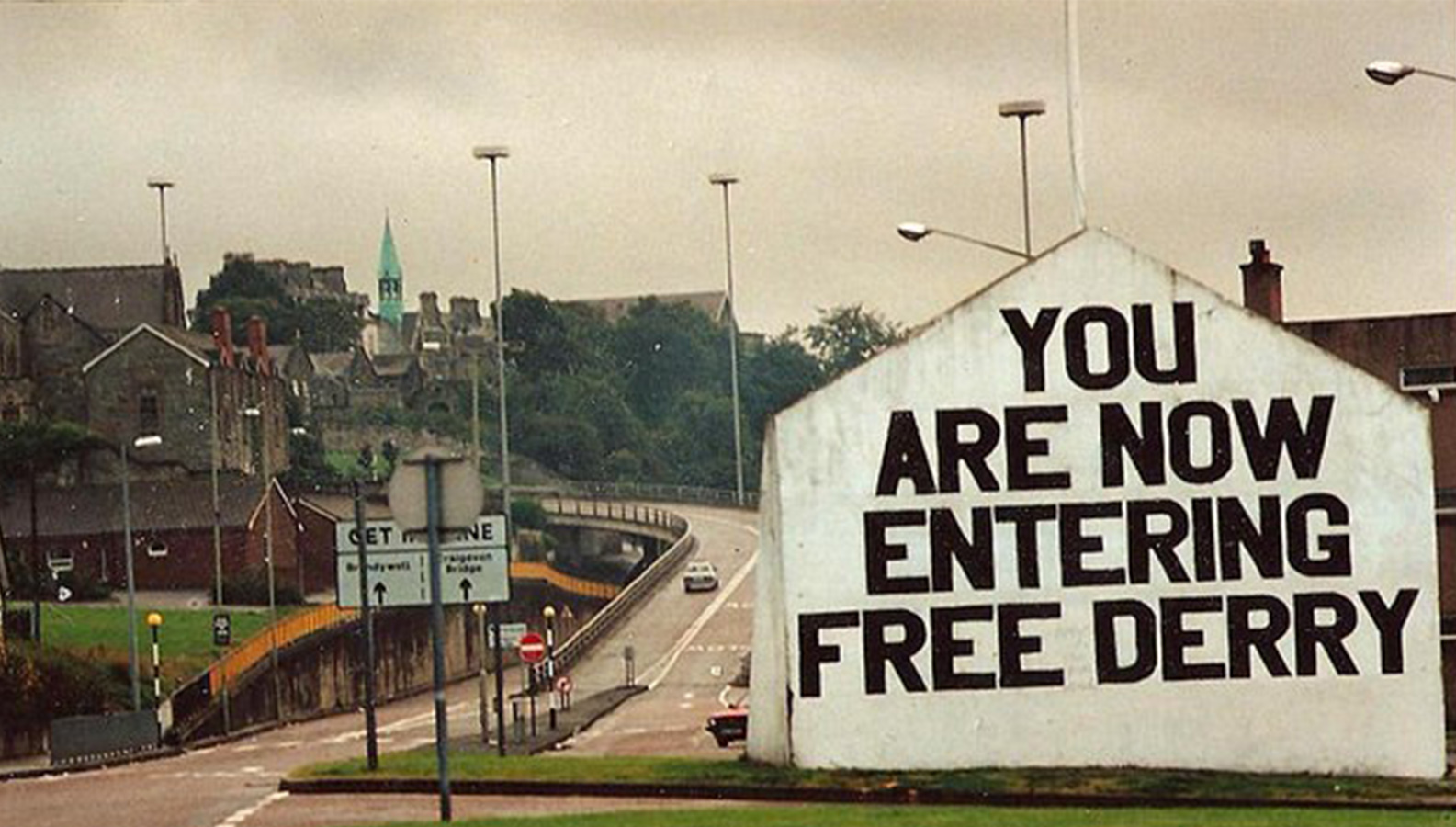

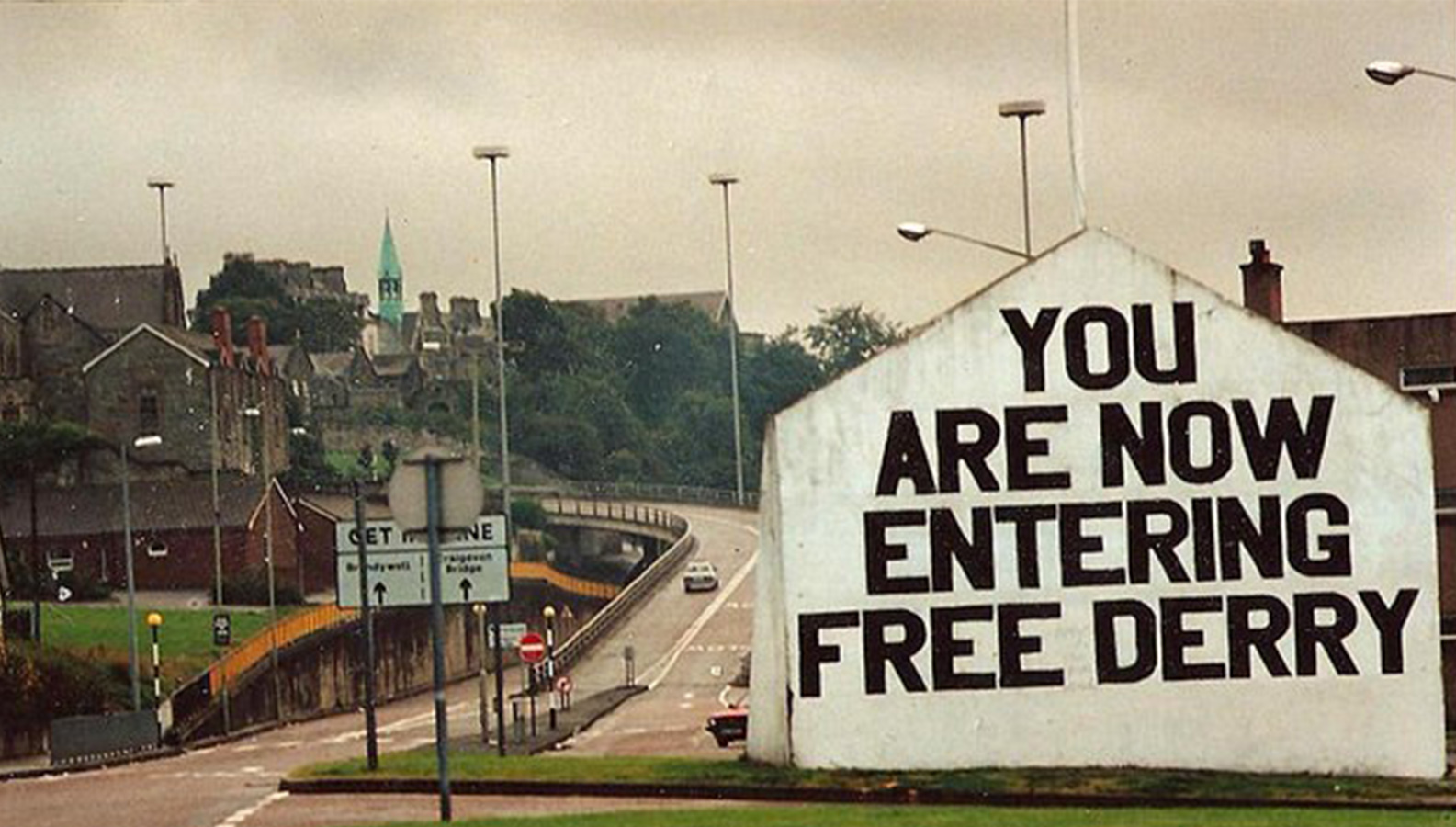

The first job I had that was not paid by the hour was in Derry. It was the spring of 2008 and I was working for a local university on a short research project to encourage residents living on both sides of a 10-foot high corrugated iron ‘peacewall’ to ‘re-imagine their built environments’. I enjoyed the work. It mainly consisted of drinking tea and trying to increase attendance at our public events. One night, only two people turned up for a talk about social enterprises. A Liverpool football match was being shown on TV at the same time.

I had never spent much time in Derry before. The first thing that struck me was how welcoming the city was to an outsider, as if simply by being there I had shown a rare faith in the place. The second thing I noticed was how little had changed since the Troubles had ended. The Good Friday Agreement was already 10 years old by then, but Derry still felt like a city at war. Nights were eerily quiet. Where Blair’s Britain had anti-social behaviour orders, in Derry dissident republicans shot joyriders and drug dealers in the kneecaps.

Our project had been funded by the European Union’s ‘peace’ programme for Northern Ireland. There was lots of irenic talk. If everyone could recognize one another, and had decent jobs, the wounds of the past could heal. The peace walls would disappear. Northern Ireland would, in the lingua franca of the civil service, become ‘normalised’.

According to the CAIN (Conflict Archive in the Internet) website, a peace line or peacewall are ‘physical barriers between the Protestant/Loyalist community and the Catholic/Nationalist community in certain areas in Northern Ireland’. Photo via Northern Ireland Foundation.

A decade later, very little feels normal in Northern Ireland. The devolved government collapsed in early 2017 and shows no sign of returning. Nobody believes that Stormont’s pledge to remove all the peacewalls by 2023 will be met. Derry retains a rich cultural life and a deep historical memory of self-organization but 95 per cent of its young people see no future in the city, according to a recent survey. The UK’s most westerly city is still its poorest. Increasingly, northern Ireland’s abnormalities seem to be infecting the British body politic once again. The Irish border could yet derail Brexit completely, or presage the hardest of breaks with the European Union. The possibility of British soldiers being prosecuted for crimes committed during the Troubles has become a rallying point for Britain’s resurgent far-Right.

And, for some in Northern Ireland, a war that left 3500 dead has never really ended. In April, dissident Republicans murdered journalist Lyra McKee during rioting in the Creggan in Derry. Two of those arrested – and subsequently released – after the killing were teenagers. They had not even been born when Good Friday was signed, almost years to the day earlier. Both are ostensibly part of the generation of young people who have grown up without the daily trauma of bombings and murders. But, like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, Northern Ireland remains haunted by twin spectres: its past and its future.

‘I’m very worried about what’s going to happen next,’ a Northern Ireland Office official in Belfast told me recently. I had asked how concerned he was about Brexit. Some Conservatives have insisted that the whole ‘Ireland problem’ is a confection, created by the European Union to keep Britain within its orbit. But behind the rictus grins and vapid talk of ‘technological solutions’ even Boris Johnson doesn’t look like he really believes it.

Northern Ireland’s sectarian geography is defined in terms of religion, but the conflict is best understood as ethnonational: Protestants overwhelmingly identify as British and unionist/loyalist; Catholics as Irish and republican/nationalist. Religious belief seldom motivates communal animosity, or at least is rarely the sole factor. But religion is a powerful mark of identity, reinforcing a Manichean view of the world. In an overplayed story, a Belfast barman asks a visiting atheist if he is a Catholic or a Protestant non-believer.

Notions of identity and sovereignty – core articles of the Brexiter faith – take on heightened meanings in such a divided society. Good Friday was an attempt to grapple with this. The solution was nuanced. Everyone could be Irish, British or both. You could want unionism, nationalism or neither. The future would be deferred in favour of the present. Everybody lost something, so everybody won something. Good Friday was also an elite project. The leaders of republicanism and nationalism, loyalism and unionism, bought into the promise of partial power in a devolved assembly in Belfast. Thousands of political prisoners were released. Weapons were decommissioned, paramilitary battalions stood down.

But in the rush to peace, the question of how to deal with the past was left unresolved. Former combatants can still be tried for crimes committed during the conflict. The Police service of Northern Ireland has a ‘legacy’ unit devoted to investigating Troubles-related crimes. It has a backlog of nearly a thousand cases.

While Belfast has been transformed, its skyline dotted with cranes, the conflict still casts long shadows. Occasionally somebody floats the idea of an amnesty or a ‘south Africa-style truth and reconciliation’ commission for Northern Ireland. But the parallel with moving on from apartheid elides a crucial distinction: unlike South Africa, there is no commonly held narrative about Northern Ireland’s recent past. Every side believes that they won their war. Blair proclaimed the ‘hand of history’ on his shoulder in 1998, as if he were an ecumenical broker and not the head of a British state that was itself a major player in the conflict. Successive governments have refused to acknowledge the reality of the war in Northern Ireland. State papers remain classified. But the past has a habit of making itself felt in the present. The trauma can only be suppressed for so long, especially with no prospect of resolution.

The trauma can only be suppressed for so long

Britain’s vote to leave the EU has placed Northern Ireland back in the UK’s political discussion for the first time in two decades. Once more, journalists are traipsing back to Belfast, filming packages for the nightly news against the backdrop of paramilitary murals. There is often a note of surprise in their delivery, as locals explain that there was not much of a ‘peace dividend’. The cameraman cuts to a lingering shot of paint peeling on a kerbstone. A passing comment about how ‘the old divisions remain’ hangs in the air.

Talking about northern Ireland’s future often ends up in an argument about its past. The most popular morning radio shows endlessly rehearse the Troubles’ darkest moments. Callers argue for hours about who is to blame for what. It is this gap between truth and falsehood – and the limits of even that language in Northern Ireland – that the journalist Patrick Radden Keefe sets out to examine in his new book, Say Nothing. The title refers to a poster of a paramilitary carrying a sten gun that appeared in working-class republican communities in Belfast during the Troubles. Beside the figure, text composed in cut-and-paste newspaper headlines, like an amateur ransom letter in a daytime murder mystery, warned, ‘Loose talk costs lives… Whatever you say, say nothing!’

Radden Keefe shows a deft understanding of the complexities of Northern Irish society and its political allegiances. As befits his primary focus on the two most important players in the conflict – the IRA and the British state – the book opens with what latterly became one of the most notorious stories of the conflict’s casual brutality: the disappearance and murder of Jean McConville and the decades-long search for her remains.

In 1969, McConville, a Protestant who converted to Catholicism when she married her late husband, fled across Belfast with her ten children as violence engulfed her city. When the family arrived in West Belfast, the family’s taxi driver was so scared that he refused to drive up to their new home in the Divis street flats. The McConvilles were left to drag their meagre belongings on foot. It was dark. The streetlights had been shot to pieces by the Royal Ulster Constabulary’s staunchly Protestant auxiliary force.

Three years after she arrived in West Belfast, McConville was abducted by the IRA. The disappearance of a prematurely middle-aged woman in a city on fire barely caused a ripple. Republicans said she was a ‘tout’, aiding the British army. But security forces’ files show no record of her name. The RUC did not conduct an investigation when she vanished. Her orphaned children were taken into care, entering Northern Ireland’s notorious institutional system. Physical and sexual abuse was rampant.

The name Jean McConville barely registered during the Troubles but, in 1999, in the new post-agreement dispensation, the IRA finally released information about her death. McConville had been taken over the border and shot. Extensive searches revealed no trace of a body. Then, in 2003, a dogwalker came across human remains on a secluded beach in County Louth, in the Irish Republic, the night after a storm. More than three decades after her death, McConville was buried. A secret IRA squad called ‘the unknowns’ killed McConville. It had long been speculated that Gerry Adams ordered her murder. In 2014, the Sinn Fein president was arrested by PSNI officers investigating the disappearance. He was released without charge.

Adams stalks Radden Keefe’s book, as he does the history of contemporary Ireland and Britain. Testimonies from former comrades paint a chilling picture of the man often referred to as ‘God’ in IRA circles. Adams is, by turns, charismatic, fiercely intelligent and utterly callous to anybody who disobeys him. But perhaps, as Radden Keefe speculates, this ruthlessness was necessary to hold the notoriously fissiparous republican movement together and ‘prevent the war reigniting’.

Such moral ambiguities run like a seam underneath post-agreement Northern Ireland. ‘Did I send people to their death for power-sharing?’ former senior IRA operative Brendan Hughes wondered aloud in his small apartment a few years after the agreement. Hughes was once among the most wanted men in Northern Ireland. A vocal opponent of Good Friday, he died in 2008 with a squadron of British soldiers still stationed above his head, on the roof of the crumbling Divis street complex.

Dozens, if not hundreds, of former Provisional IRA volunteers have joined the ranks of dissident republicanism. Some have joined the new IRA, which claimed responsibility for Lyra McKee’s killing. Others prop up bars across border counties, bemoaning former comrades who ‘sold out to the Brits’ and encouraging a new generation to take up arms, no matter how overwhelming the odds.

The soldiers became synonymous with the worst of the Troubles

If the republican threat has not gone away, then the British state’s own role in the conflict remains shrouded in mystery. The British Army were famously welcomed by Northern Ireland’s beleaguered Catholic minority in August 1969. But it quickly became clear that the army would not be delivering nationalists from a sectarian RUC. Instead, the soldiers became synonymous with the worst excesses of the Troubles: internment without trial, collusion, and even summary execution.

Denialism over the reality of Whitehall and Westminster’s role in Northern Ireland has almost become Conservative party policy under the watchful eye of their de facto coalition partners the Democratic Unionist Party, a political party born out of an extreme Protestant sect. When the Public Prosecution Service announced that a single paratrooper will stand trial over the Bloody Sunday shootings of 1971, the Ministry of Defence said it would cover the soldier’s legal costs. Tory MP Johnny Mercer resigned the party whip in protest at the prosecution.

The British state has plenty to fear from close attention being paid to the Northern Irish conflict. For decades, security forces worked closely with loyalist paramilitaries. In June 1994, in the sleepy County Down hamlet of Loughinisland, six Catholic men were shot dead as they watched the Republic of Ireland play Italy in the World cup. An Ulster Volunteer Force gunman shouted ‘Fenian bastards’ before opening fire with an assault rifle. (‘Fenian’, a reference to an archaic Irish republican movement, is a synonym for Roman Catholic.)

A 2017 documentary, No Stone Unturned, identified a chief suspect in Loughinisland as a police informer. In the aftermath of the attack, key evidence and documents were destroyed. The rifle used is alleged to have been part of a shipment smuggled into Northern Ireland by a senior Ulster Defence Association figure and British agent. Such collusion between the state and loyalist gunmen is hardly unique. When Sir John Stevens investigated the extent of the problem he said he had ‘never found myself caught up in such an entanglement of lies and treachery.’

Nobody was ever charged with the Loughinisland murders. Last August, dozens of armed PSNI officers arrested the journalists behind No Stone Unturned. Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey were held on suspicion of the theft of sensitive information from the police ombudsman. In March, their bail was extended for a further six months. Finally, in June, the case was dropped.

The decision by the police to turn their attention on investigative journalists marked another deterioration of democratic norms in Northern Ireland. During the conflict, the myriad pressmen huddled in Belfast’s Europa Hotel were routinely fed false information but were generally left unmolested. Many of the journalists who forged their careers during the conflict tend to look back on Northern Ireland as a simpler age. A time when car bombs were delivered with telephone warnings.

Originally at the corner of Lecky Road and Fahan Street, the slogan was first painted by John Casey in 1969. Photo via Geograph Ireland.

Only two journalists have been killed in Northern Ireland since 1969. Both died in the years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. This sense of a barely subcutaneous violence suffuses A Woman Takes Her Son to Be Shot, Sinead O’Shea’s powerful recent documentary about life on the fringe of Derry’s dissident republican world. In one particularly memorable scene, a teenage boy says that he and his friends want to see the Troubles return. ‘The madness, the riots, the shooting, the bombings, everything.’ Anything is preferable to the hopelessness of a Derry sink estate.

In the days after Lyra McKee’s killing, the world’s attention turned on Northern Ireland. There were reports from Derry where, in an almost unprecedented show of bravery, activists daubed red handprints on the headquarters of a splinter republican group widely seen as the new IRA’s mouthpiece. The parish priest officiating at McKee’s funeral was given a standing ovation when he chastised political leaders for their failure to compromise.

There are wider signs of change. Both the non-sectarian Alliance Party and the Greens made significant gains in may’s local elections. Many young people reject the tribal identities of ‘Orange and Green’ and look enviously at the more relaxed social mores South of the border: in the last few years the republic has passed referendums to allow same-sex marriage and abortion; Northern Ireland, by contrast, remains the only part of the UK where both are denied. The number self-defining as religious seems to be in decline. (This is hard to measure accurately as the Northern Irish census reassigns ‘non-religious’ respondents as Catholic or Protestant based on cultural markers such a location and education.) But the past still suffuses the present.