The Second Karabakh War commenced in late September of 2020 when Azerbaijani forces launched a major offensive against the Armenian-controlled Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh, or Artsakh. The offensive broke a 1994 ceasefire that had frozen the first war, one of the ethnic conflicts that erupted in the Soviet southern tier before the union’s formal demise in 1991. The conflict initially centred around the so-called Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), an Armenian-populated administrative unit within the Azerbaijani SSR. The first war ended with a resounding Armenian victory. By the time fighting had concluded, violence had ‘unmixed’ much of the region, with no members of one ethnicity continuing to reside in territory controlled by the other.

The 2020 war was much different. Armed with intelligence and material support from Turkey and Israel, Azerbaijan pressed its advantage. By the time fighting concluded in November 2020 with a Russian-brokered ceasefire, Azerbaijani forces had recaptured the districts surrounding the former NKAO and had effectively cut off the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh from Armenia. Less than three years later, and with implicit Russian consent, Azerbaijan again broke the ceasefire unilaterally, launched an offensive against Karabakh Armenians’ meagre defences, and sent over 100,000 Armenians into exile, thus completing a campaign of ethnic cleansing. After operating for twenty-six years as a de facto state, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh had ceased to exist.

The government of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, which oversaw the 2020 defeat, has spent the past year seeking a peace agreement – one that Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev is less inclined to secure, given Armenia’s lack of leverage and his need to displace domestic tensions onto the ‘perpetual’ Armenian enemy. As Armenia attempts to break with Russia (its main security guarantor since 1994) and begins to make overtures to entering the western orbit – to growing discontent from civil society – the renewal of full-scale war between the two countries lurks ominously in the background.

The possibility for more bloodshed between Armenia and Azerbaijan is no anomaly in a region where destabilization is the order of the day. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, dramatic shifts in regional and global politics had taken place, as the intervention of Turkey and Israel into what had been ‘Russia’s backyard’ in the buildup to the 2020 war clearly demonstrate. New regional powerplays in the Caucasus are a concomitant of ‘periphery-remaking’, which has been ongoing since at least the 1990s, when this region of the former Soviet Union was originally drawn into global circuits of capital. In turn, capitalist formations in the Caucasus are historically constituted, the products of Soviet modernization policies and the particular dynamics of the post-socialist transitions that endowed them with institutional and social legacies for their post-independence development.

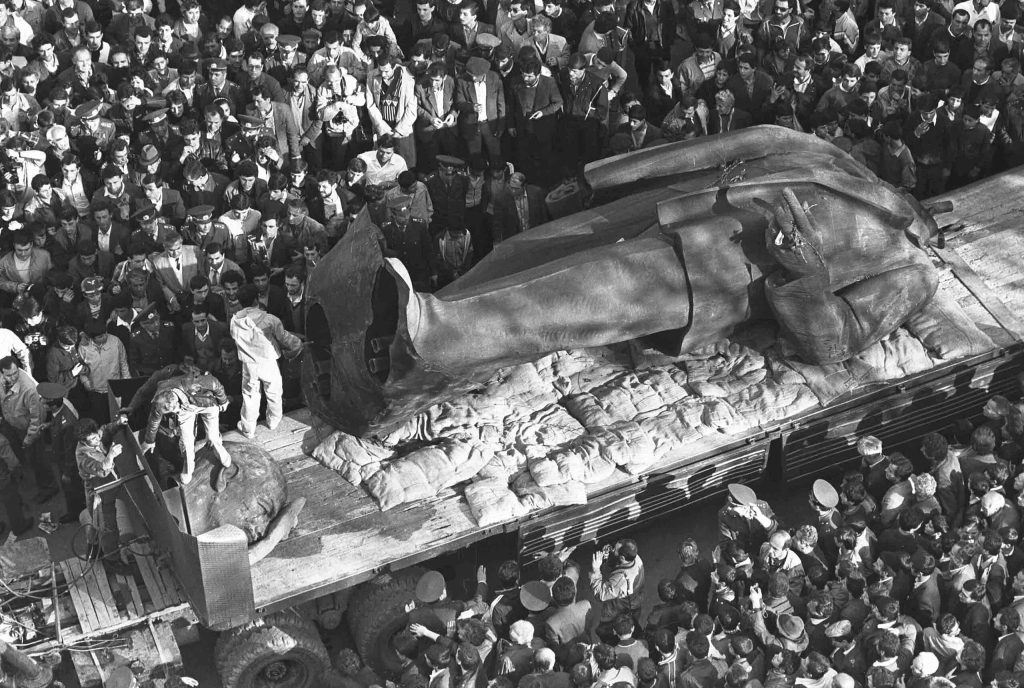

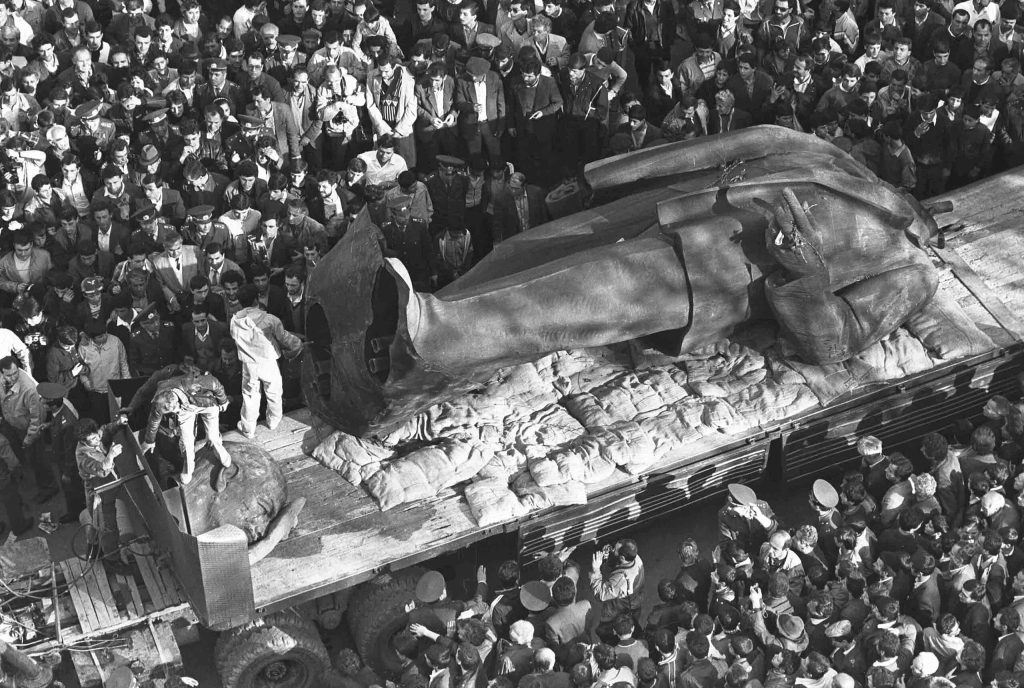

Lenin Statue Removal in Yerevan, 13 April 1991. Image: Armenian Museum of Photo and Video Materials / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Armenian national development must therefore be seen as part of a broader regional pattern of state and society transformation in the post-communist southern tier. Armenia, in particular, presents the case of an organic and mobilized civil society which increasingly finds itself in conflict with a state apparatus that lacks the domestic and international relative autonomy to pursue a postwar project of national restoration. The divergent development of Armenia and Azerbaijan after the first Nagorno-Karabakh War (which began as a late Soviet civil war that subsequently took on nationalist tones) speaks to the particularities of their respective transitions to capitalism, as each country’s material and demographic constraints positioned them within the expanding capitalist world-system.

Soviet modernity as prelude to the post-Soviet

Post-Soviet societies are frequently measured by the aspirational, meaning that are defined more by their supposed deficiencies than the actual lived experiences of their citizens. The veritable cottage industry of political science scholarship on post-Soviet transitions that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s implicitly juxtaposed newly independent states against idealized versions of the ‘developed’ polities of the (western European and North American) core of the world-system. The active role played by ‘civil society’ in the unravelling of communist regimes conditioned the expectations of both western and domestic observers for what would come after the transition. The result was an interest in – and overemphasis on – NGOs and party systems as the markers of a successful transition: domestic economic liberalization and entry into the common European market, to be overseen by depoliticized, expert governance. To the extent that civil society and the demos would factor into the equation, its interests were largely expected to align with – or at least, not to fundamentally disrupt – the two main imperatives of liberalized markets and technocratic management.

This framing directs the focus away from the forms of political contention that had emerged during the Soviet period and continued to organize both economic and political power, first during Perestroika and then after 1991. This is especially true for understanding not only the Caucasus, but what has been referred to as the former Soviet Union’s ‘southern tier’ – its peripheral and semi-peripheral regions, united by their largely agricultural economies and the persistence of patrimonial and customary social relations, transformed but not erased by the modernization projects of the Soviet developmental state.

The rich cultural and ethno-linguistic diversity of the southern tier made it an especially important site of early Soviet nationalities policies. These policies, which began soon after the Russian Civil War and continued in different forms until 1991, served several ends. They took aim at what Lenin denounced as ‘Great Russian chauvinism’, which had inculcated a sense of Russian ethnic superiority during tsarist rule. Through the concerned policy of cultural and pedagogical korenizatsiia, they sought to build up political nations in places where kinship, tribal, and customary ties had previously served as the means of organizing social life. Rather than a ‘breaker of nations’, as is often maintained by contemporary accounts that trace a seamless connection between the tsarist and Soviet periods, the Soviet Union standardized non-Russian languages, created national academies of science in every union republic, reproduced national symbols (from coats of arms and flags to postage stamps), patronized national culture (including national literary canons, folk music, dance, and cuisine), and then propagated these through national media (local press, radio, and later television), state-sponsored public events and holidays, and public schools.

Crucially, these policies also aimed to root soviet power in non-Russian, peripheral regions by promoting the elevation of local cadres into both the Communist Party and the Soviet state bureaucracy. Collectively, nationalities policy embedded Soviet legitimacy in the language of the nation, which could become a tool for accessing state power. National framings thus informed the shape that the Soviet nomenklatura – the bureaucratic and administrative elite that ran the country – would take, particularly in the southern tier. State offices and party organs in the republics remained subordinate to corresponding all-union institutions; still, locals themselves wielded state power throughout the republics, simultaneously integrating and investing them within Soviet structures of power. Local cadres integrated into the Soviet hierarchy were better equipped to respond to local concerns, whether they be couched in economic, social, or even national terms. Members of the two other principal social layers that constituted Soviet society, the intelligentsia (who rose through institutions of higher education presided over by the national academies of sciences) and the proletariat (comprising both urban workers and collectivized rural labourers), therefore wielded the material and symbolic resources to both establish links to their respective nomenklaturas (shared language, shared customs, and, in some cases, shared kinship) and contest their authority.

By the 1970s, nationalities policies in the three Caucasian republics had produced a generative, but potentially volatile, stasis between two countervailing forces. On the one hand, there were active and mobilized citizens that could make claims on the state, demand public goods, and defend their rights as workers and citizens. On the other was a nomenklatura with reactionary tendencies reluctant to share power with other groups in society, yet content with the relative autonomy from Moscow that the confluence of nationalities policies with social hierarchy had granted them. Strong leaders able to balance out these social forces while protecting their republic’s relative autonomy (both vis-a-vis Moscow and their own societies) came to the fore in the Soviet Caucasus – Karen Demirchian in Armenia (r. 1974-88), Heydar Aliyev in Azerbaijan (r. 1969–82, before promotion to full membership in the Politburo), and Eduard Shevardnadze (r. 1972–85, before appointment as Minister of Foreign Affairs) – where they ruled either directly or through their own patronage networks.

By the 1980s, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia were all distinguished by mobilized publics, constituted by highly nationalist intelligentsias and an under-organized ‘subproletariat’ composed of workers in seasonal agriculture and the informal economy. The economic stagnation that the perestroika reforms attempted to address had made it increasingly difficult to reconcile Soviet civil society demands with the nomenklatura’s prerogatives. In the Caucasus, the economic inefficiencies inverted the democratic elements of nationalities policies – which had provided the intelligentsia and the proletariat with the means for accessing state power, and thus, material benefits – by promoting the ethnicization of the nomenklatura’s patronage networks as they scrambled to claim goods and services. Contests over the ability to exploit resources or control unofficial markets consequently assumed a national character. Perestroika’s economic reforms had the unintended consequence of exacerbating the ethnonational cleavages that had developed within nomenklatura networks over the preceding decade. New financing schemes, support for new enterprises, and even limited concessions to private initiative placed a new premium on proximity to the nomenklatura and local Communist Party officials.

These contradictions between socialist governance, nomenklatura reaction and nationalization, and capital accumulation manifested most dramatically in the ethnic conflicts that broke out in the Soviet Union’s dying days. In Armenia, the Karabakh Movement (the demand that the NKAO be placed within the Armenian SSR) was led by a decidedly anti-nomenklatura Armenian intelligentsia, who were joined in their efforts by the proletariat. Similar intelligentsia-led movements developed in both Azerbaijan and Georgia. In the NKAO itself, however, the movement for unification with Armenia grew out of long-standing economic resentments and was led by the local nomenklatura within the Communist Party. For decades, the Armenians of Karabakh had protested economic discrimination on the part of Azerbaijani authorities. The ethnicization of patronage networks was especially painful for the NKAO elites, who found themselves at a competitive disadvantage with the Azerbaijani nomenklatura. Perestroika presented the NKAO nomenklatura with an opportunity to pursue economic independence from Baku, which they did by attempting to deepen their connections to firms and enterprises that were dependents of the nomenklatura in the Armenian SSR. The attempts of the Azerbaijani SSR to curtail Karabakhi Armenians’ economic activities (with support from Moscow) established the contours for the ethnopolitical conflict that was to follow.

Ruling the post-Soviet void

Even before the formal collapse of the Soviet Union, democratic elections in the Caucasus swept popular candidates into executive office. Yet this did not herald the victory of the intelligentsia. By early 1992, Eduard Shevardnadze had returned to power in Georgia; Heydar Aliyev followed suit in Azerbaijan, where he reassumed control in late 1993. In Armenia, the old guard would only fully restore its authority in 1998 through a palace coup that deposed the democratically-elected Ter-Petrosyan in favour of Robert Kocharyan, a former party cadre who had been at the forefront of the Karabakhi independence movement. The inability of other classes to dislodge these unpopular regimes would come to characterize post-Soviet politics.

With the benefit of hindsight, the restoration of the nomenklatura appears inevitable. Democratization, however earnest it may have been, directed popular energies into hollowed-out state institutions and parliaments that lacked either the ability or the knowhow to curtail the economic prerogatives of the former nomenklatura-turned-oligarchs. It also left the winners of elections – the intelligentsia – to shoulder the blame as social welfare programs flailed under new market pressures, driving a wedge between the intelligentsia and the proletariat, and consequently weakening the political capacity of each. Democratically elected presidents saw their popularity disappear almost overnight. Social cohesion frayed at all levels of society, with all three republics mired in ethnic conflicts: Georgia fighting against ethnic separatists in Abkhazia, and Armenia and Azerbaijan engaging in a late-Soviet civil war over Karabakh.

While the collapse of Soviet power and the disintegration of the Communist Party had left the nomenklatura vulnerable at the ballot box, it was nevertheless best positioned to benefit from this unravelling of society and this weakening of state capacity on the periphery. Perestroika helped to insulate the nomenklatura from popular pressure by catalysing the degradation of the party-state. Though in a new guise, the party – whence the nomenklatura derived institutional power – retained command of economic functions that were increasingly emancipated from political control. The privileged social and political position that the nomenklatura had retained left them well placed to navigate the wreckage of political collapse and to reappropriate the state. The fusion of state institutions with the nomenklatura’s economic power, established through long-standing personal networks, reconstituted their class power as a comprador-national oligarchy. Across the Caucasus, these respective oligarchies would find themselves with multiple levers to create durable regimes, as they oversaw the development of imitation democracies marked by significant discrepancies between putative constitutional principles and the reality of authoritarian rule.

Consonant with the ethnicization of economic networks through provincial and regional communist party bureaus, the oligarchs presented themselves as the standard bearers of patriotic discourse. In so doing, they completed the reversal of Soviet nationalities policies, turning national claims into an instrument for legitimizing top-down hierarchy rather than a mechanism for contesting power from below. Political culture took a reactionary turn. In the hands of the oligarchs, national discourse became a tool for suppressing dissent by casting political opponents as foreign agents or worse, traitors. NGOs, which in some cases tried to provide desperately needed services that the state could or would not, found themselves under intense scrutiny for their connections with either foreign governments or aid agencies.

The oligarchs further burnished their patriotic credentials by inviting veterans and warlords – who were often former nomenklatura themselves – into their coalition to share in whatever spoils they had pilfered from the public treasury. Control of security forces – which Shevardnadze and Aliyev secured by purging potentially dangerous officers – tightened the oligarchs’ grip. Aliyev, with the support of Turkish intelligence, contained and later defeated an uprising led by the military officer Surat Huseynov. A nomenklatura-backed military council in Georgia, which was openly at war with Gamsakhurdia, invited Shevardnadze back into the country to restore order. The Armenian case may be the most instructive: led by the defence minister, former nomenklatura from Karabakh who had been brought into the government allied with local oligarchs and a prominent war veterans group (the Erkrapah Volunteer Union) to depose Ter-Petrosyan and install the reactionary Kocharyan as president.

The militarization of society in each country tightened the oligarchs’ grip as they developed their imitation democracies. Despite the obvious gap between constitutional ideal and authoritarian practice, no sociopolitical force could muster any serious challenge to the imitation democracies of the Caucasus lest they provoke the repressive apparatus of the state. To perpetuate the fiction of a competitive democratic system, the regimes fabricated parties – not to represent the people to the state, but to present oligarchic interests to the electorate as those of the nation. In Georgia, Shevardnadze’s Citizens Union operated as the public-facing clearinghouse for oligarchs and warlords with civil society to legitimize the Brezhnev-style regime that had emerged after the fall of Gamsakhurdia. Heydar Aliyev’s New Azerbaijan Party, founded in 1992, established a patrimonial authoritarian state, fully consecrated when the presidency passed from father (Heydar) to son (Ilham) upon the former’s death in 2003.

Within parliamentary-democratic states, practices like universal suffrage, the pluralism of political parties and organizations, the division of power between executive and legislative branches, and juridical autonomy work together to permit an organic circulation of hegemony among different fractions. Lacking these mechanisms for creating a power bloc among competing elites and for linking the state to the societies over which they presumed to rule, regimes in the Caucasus increasingly resorted to coercion, graft and opaque nationalism to deflect social dissent not already neutralized by parliamentary theatre.

The Azerbaijani regime, especially under Aliyev junior, has anchored its social and political legitimacy in a particularly rabid Armenophobia. This has culminated in the destruction of the rich Armenian cultural heritage on territories that, now under the control of Azerbaijan, were once constituent parts of medieval Armenian kingdoms. In turn, Armenia’s own facsimile party, the Republican Party of Armenia, channelled the nomenklatura-turned-oligarchy into the state apparatus, in part by vesting its own legitimacy on two pillars. It claimed the writings of Karekin Nzhdeh, a hero of the first republic (1918-20) who later promoted protofascist thought, as the foundation for the party’s conservative ideology. More practically, the Party – with its coalition of veterans, warlords, and Karabakhi oligarchs – adopted a hardline on negotiations with Azerbaijan over the final status of the former NKAO. In doing so, it indentured itself to Russia, accepting economic subordination to Russian capital in exchange for security guarantees – guarantees that have since proven worthless.

Opponents of these regimes have therefore had to strike a delicate balance – their dissent had to speak across societies fractured by economic and political collapse while also resonating with the reactionary political discourse that the oligarchy had established as the political mainstream. On occasion, this has meant that single-issue campaigns appealing to people’s emotions – protests against increases in bus fares, electricity costs or bread prices – have compelled the regime to make begrudging concessions. But more frequently, it has meant that oppositionists have tried to outflank the regimes to their right. The lone exception to this rule was Ter-Petrosyan’s failed attempt at a return to power in 2008.

Armenian war grave in Sosh, Nagorno-Karabakh, 2017. Image: Սամվել Սարգսյան / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Class, state and civil society

The thirty-year period between 1991 and 2021 could be interpreted through the lens of democratic backsliding from liberal to imitation democracy. However, this one-sided focus on the erosion of representative institutions and the rule of law masks not only the persistence of state structures after independence, but also the changing balance of class forces among the different fractions that enabled the nomenklatura-oligarchy to maintain its power.

The initial liberalization of the post-socialist transition, and the temporally condensed period in which it took place, raised civil society’s expectations about inclusion into the liberal geoculture, understood as ‘norms and modes of discourse widely accepted as legitimate within the world-system.’ While this produced highly uneven results, it did generate new, geographically transmissible repertoires of contention that could be used to challenge, if not entirely overthrow, elite structures, giving rise to the post-Soviet Colour Revolutions of the early millennium.

In Armenia, the patterns of class conflict and their political expression unfolded in roughly decade-long intervals of elite retrenchment punctuated by moments of democratic mobilization. Between 1991 and 1998, the administration of Ter-Petrosyan found its social support in an alliance between the intelligentsia, the subproletariat, and an upwardly mobile comprador bourgeoisie whose aspirations ran afoul of the nomenklatura. Following Ter-Petrosyan’s removal from power, the marginalization of the intelligentsia and the receding of the subproletariat to the background, the ruling bloc of the Kocharyan-Sargsyan regime rested upon an alliance between the oligarchs and the security forces, even as the former fought among themselves. Ter-Petrosyan’s attempted return in 2008 and the violence that followed that year’s presidential election prompted a political crisis. Divisions between oligarchs had created a structural opening for mass mobilization by the intelligentsia and civil society movements – the door to which Kocharyan slammed shut by unleashing violence on peaceful protestors during the infamous events of 1 March 2008, thereby also leaving Sargsyan holding a bloody mantle during his own time in power.

Ten years later, in 2018, a new round of mass demonstrations against Sargsyan’s attempt to circumvent term limits catalysed the ‘Velvet Revolution’, marking a recomposition of the hegemonic bloc: while much of the old oligarchs have been politically marginalized (even as they retain their economic power), the new regime has brought forward an alliance of the domestic bourgeoisie, neo-intelligentsia and subproletariat, which has returned to the political scene. However, like the other colour revolutions – Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004 and Kyrgyzstan in 2005 – the Velvet Revolution constituted a turnover in political power with practically no corresponding social or economic changes.

Since 2018, Pashinyan’s government has overseen the persistence of the ‘old regime’ of oligarchic economic and legal structures. While the government has targeted specific figures (for example using its parliamentary majority to pack the judiciary and jail Kocharyan), the economic power and influence of the oligarchy remains largely untouched. Despite Pashinyan’s overtures to the West, the Armenian economy remains closely entwined with and dependent upon Russia as its largest external market. The massive privatization of Armenian companies that followed soon after independence and increased during the Kocharyan regime means that, today, key strategic industries are controlled by Russian capital – to the benefit of the Armenian comprador bourgeoisie with ties to the Russian core. According to a 2023 report, Russia is Armenia’s top foreign trade partner, supplies the overwhelming majority of its oil and natural gas, and holds sizable shares in its transportation and extractive industry infrastructure. To maintain rural support under these conditions, Pashinyan’s government has also taken a leaf from the book of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan by promoting construction projects in public works and housing.

If, from the 1970s on, western political parties have increasingly become transmission belts for representing the state to the people, then it is questionable whether the Armenian parties of power can even attain that level of coherence or organization. At best, they are facsimiles of parties that create the basis for oligarchic power. A quintessential ‘hollow party’, Pashinyan’s Civil Contract has no discernible political ideology and a shallow connection to Armenian society. Belying the appeal to liberal, educated, white-collar professionals that Pashinyan’s alleged westward turn might indicate, the party’s role is more of a patronage network to reward regime loyalists. While it is largely opposed by the traditional intelligentsia of Yerevan, the current basis of the government’s strength is among working class, rural Armenians, especially in the north of the country, and in the technocratic social layers whose previous aspirations were blocked under the oligarchic regime.

Here, as elsewhere in the post-communist world, we see the absence of robust mass parties and the decline of institutions through which popular, working-class demands can be made upon the system. The alliance between the working class and the intelligentsia that was so crucial during the independence movement became disorganized by thirty years of economic reforms, which have only continued under the Pashinyan government. Since independence, the country’s peripheral status within the regional division of labour has also introduced a contradiction into the working class: on the one hand, a large number of low-skilled labourers finding employment as migrant workers in the Russian metropole; on the other, rapidly developing IT and service sectors that seek greater integration into the transnational circuits of capital beyond the Russian sphere. Even as the working class remains a potential political force – it was the wildcat strikes in Yerevan’s working-class neighbourhoods that marked the turning point of the 2018 protests – these structural factors pose serious challenges for organizing it into a durable political force.

As elsewhere across the world, it has not been the working class but the middle classes that have emerged as the most visible political actors in recent years. Such mobilizations marked the emergence of the ‘new petty bourgeoisie’ onto the political scene – a class fraction with divergent and fragmented social, economic and political claims. During the Velvet Revolution, a national consensus formed around Pashinyan’s anti-corruption message. Even as it continues to emphasize corruption as the main economic problem, the government has done little to address citizens’ concerns. Anti-corruption messaging may bring people into the streets, but it lacks inherent political content and is just as liable to be deployed by one fraction of elites against another as it is by the popular masses against those in power. In ejecting certain elites but maintaining the continuity of both political and economic structures, Armenia’s Velvet Revolution neatly fits into the broader trend of anti-systemic, popular mobilizations that typified the ‘mass protest decade’ of the 2010s.

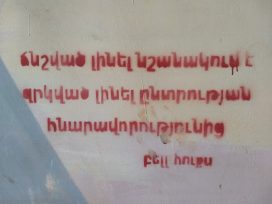

Four years after the country’s resounding defeat in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, Armenian civil society remains highly mobilized but lacking the institutional means by which to actualize popular grievances in the political arena. The incorporation of Armenia into the capitalist world system and its liberal geoculture enabled activists to draw upon new ‘repertoires of contention’ to challenge entrenched elites. However, neither these sporadic mass protests, nor the conventional activity of work through western-oriented NGOs, have been able to dislodge the oligarchy.

Regional conflict amidst the fraying liberal order

After 1991, the Transcaucasus was gradually drawn into the global circuits of capital – but in an uneven and fragmented way. From the 1990s onward, the ‘post-Soviet’ became a subcomponent of the new, truly global capitalism. The shared legacy of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia from out of Soviet modernization endowed them with similar institutional and social conditions for post-independence development, even as changes in the internal and external balance of forces have since created diverging trajectories. Azerbaijan has become a repressive (and potentially brittle) petrostate that continues to pursue a nation-building project; Georgia, desperately seeking closer political and economic ties with Europe, finds itself divided between a pragmatic government and a mobilized pro-western civil society; Armenia, meanwhile, is in the most dire position of the three, its statehood in question more than it has been for a century.

The fissures in the American empire that first became visible during the War on Terror and the invasion of Iraq, followed by the descent of the fleeting democratic ebullience of the Arab Spring into military dictatorship and civil war, now signal the retreat of American hegemony across the Eurasian sphere. This retreat has created pathologies in unevenly developed regions of global capitalism, generating proxy conflicts involving both regional and global powers from Syria to Ukraine to the Transcaucasus.

In the latter case, a convergence of factors – the weakening of Russian regional influence, the growing aggressiveness of Turkish imperialism, the sharpening of the Israel-Iran rivalry, and now, Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza – have all contributed to the Aliyev regime’s intransigent stance, even after the Second Karabakh War. The War and the potential for future violence in the region thus should be seen as a consequence of the fraying of the myth of the liberal international order that emerged during the Cold War under the aegis of American global hegemony.

Within this changing regional dynamic, the Pashinyan government remains trapped in the security dilemma that has overdetermined Armenian domestic politics since 1994. But in its current pivot away from Russia and toward the West, it has appealed to liberal geocultural norms – human rights, transnational commerce, national ‘development’ and multilateralism in security – that the global events of the past two decades have rendered increasingly hollow, as we enter a phase of American hegemonic decline with no clear substitute. As Russia, Turkey, Iran and the United States continue to vie for influence in the post-Soviet ‘southern tier’, the prospects for regional stability are bleak.