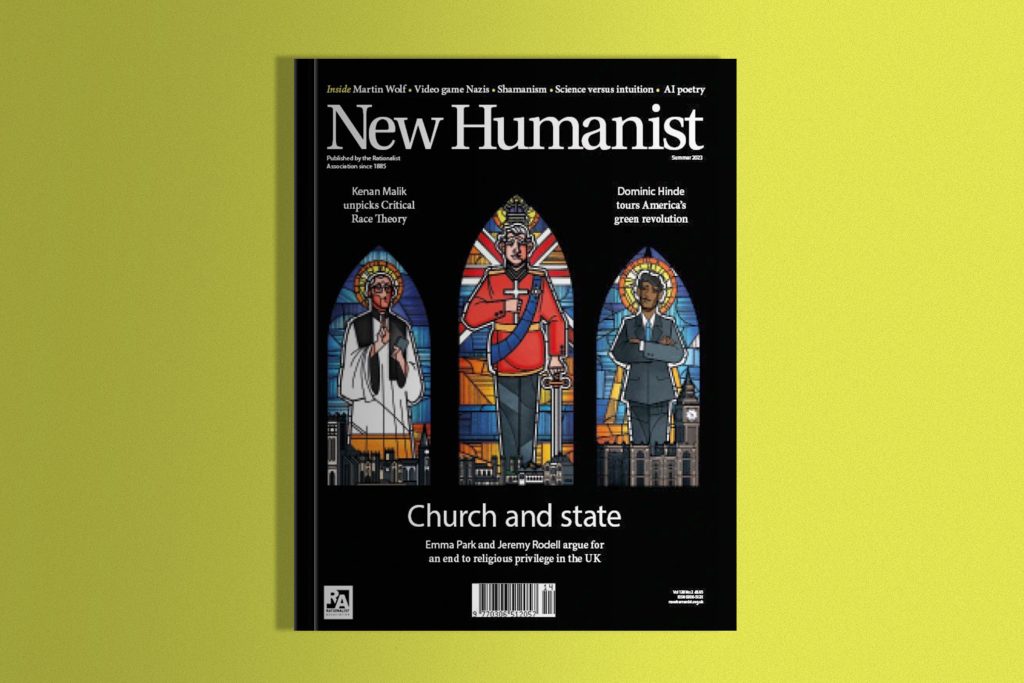

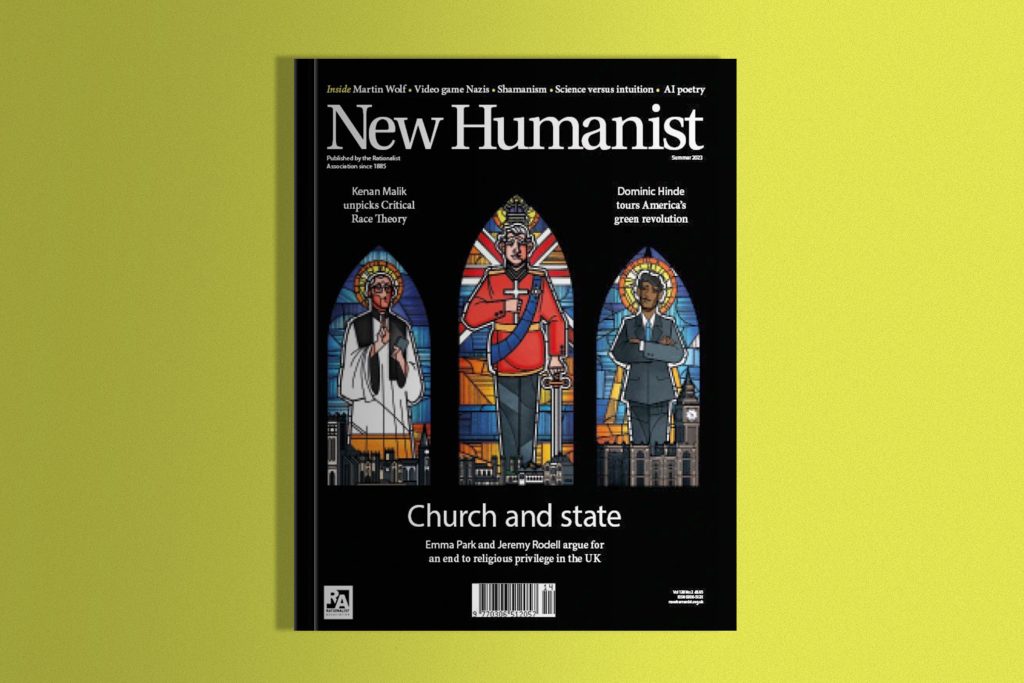

Coinciding with the UK’s coronation celebrations, New Humanist publishes a dossier on England’s union of Church and state. From the latest census, it’s known that most British people no longer identify as Christian. And yet the wealthy Church of England continues to be supported by the state. New Humanist contributors think it’s time to reassess the privileged role of a dwindling religion.

Denying reality

‘English Anglicanism is literally dying,’ writes Humanist Jeremy Rodell. ‘The main driver of decline is not Anglicans leaving, but children of Anglicans not carrying on with the faith.’ This dropout is occurring despite the Church’s management of a quarter of England’s state-funded primary schools: now only 1% of the country’s under-25s consider themselves Christian.

The Archbishop of York, asserting that ‘the church of Jesus Christ is not an organisation that lives or dies by graphs going up and down’, has proposed establishing 10,000 new churches in ten years. But Canon Angela Tilby questions whether, ‘in a desperate attempt to avoid facing… reality, we have entered a state of corporate psychosis: a leap into false consciousness.’

Rather than wild expansion plans, Rodell suggests a community preservation strategy. ‘A diminished Church cannot expect to protect a legacy of enormous wealth and tax-exempt investments’, she argues; instead, it should attempt to preserve its substantial ‘foodbank and playgroup’ infrastructure. ‘As the traditional model of churches and vicars becomes increasingly unsustainable, new solutions will be needed to keep the social-action baby while the Anglican bathwater flows away.’

Emma Park, editor of The Freethinker magazine, asks: ‘Why is merely “advancing religion” enough to qualify an organisation for the privileges of a charity?’ She quotes Britain’s Charities Act of 2011, whereby it is enough for a charity to ‘increase belief in the supreme being or entity that is the object or focus of the religion.’

However, ‘how a secular body like the Charity Commission is supposed to determine what is or is not a religion’ is a ‘knotty question’. And whether the charity engages in harmful practices such as ‘circumcision, political extremism and discriminatory religious “courts”’ remains underexamined. ‘More government money is being used to prop up the Church of England,’ writes Parks. ‘The only just way forward would be to repeal the clause.’

Critical race theory

Kenan Malik charts the life and beliefs of Derrick Bell, the godfather of ‘critical race theory’. According to Bell, because racism was ineradicable, antiracist action would not only “not lead to transcendent change” but it “may indeed, despite our best efforts, be of more help to the system we despise than to the victims of that system whom we are trying to help.”’

Despite remaining largely unknown, Bell’s perspective has gained ground in America’s antiracist movements and beyond: ‘Challenging racism while at the same time believing it to be ineradicable has inevitably shaped the character of antiracism today, writes Malik. ‘It has prompted a shift from campaigns for material change to demands for symbolic gestures and representational fairness.’

White people’s adoption of tropes from black culture is under increasing scrutiny. But Malik questions the backlash against ‘cultural appropriation’: ‘What does it mean for music or a cuisine – or “pain” – to “belong” to a culture? And who gives permission for someone from another culture to use such cultural forms?’

‘Gatekeepers shield not the marginalised but the powerful,’ he warns. ‘Racism itself is a form of gatekeeping, a means of denying racialised groups equal rights, access and opportunities. The policing of cultural appropriation is no different, though the polarities have been reversed, and it is executed in the name of antiracism.’