The defence of democracy in France must continue to be a republican discourse, not one of libertarian nationalism. Critics of ‘Islamo-leftism’ engage in the very same process of blame-shifting that they accuse their opponents of – sometimes rightly.

On Friday 13 November, Paris suffered an unprecedented set of terrorist attacks less than a year after those targeting Charlie Hebdo and a Jewish supermarket. Once again, we review the responses of Eurozine partner journals, associates and authors.

In openDemocracy (UK), historian and journalist Vijay Prashad expresses horror and outrage at a “week of horrible carnage – bomb blasts in Beirut and Baghdad and then the cold-blooded shootings in Paris”. Prashad also cites French president Francois Hollande initial response: “We are going to lead a war which will be pitiless.”

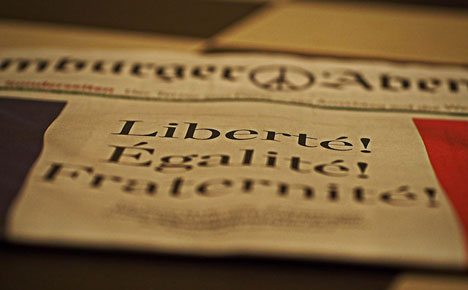

Photo: Torsten Behrens. Source:Flickr

“But the West – including France – has already been at war against both ISIS and groups like ISIS. Who else will be attacked?”, asks Prashad. “Will the strategy change? Will western leaders be able to take a longer view than one constrained by the emotional reaction of the present and be able to see past the reflex of more war? Would the western intelligentsia and its leadership be able to acknowledge that some of the strategic choices made in the West have only exacerbated animosities and conjured up a great many threats? It is unlikely”.

However, Eurozine contributor and Flemish author David Van Reybrouck also takes Hollande to task for his “extraordinarily reckless choice of words”. Van Reybrouck first quotes directly from Hollande’s speech of 14 November:

What took place yesterday in Paris and Saint-Denis is an act of war, and when faced with a war the country must take appropriate measures. An act perpetrated by a terrorist army, Daesh (IS), against all that we are, a free country in dialogue with the entire planet. An act of war that was prepared and planned elsewhere, with internal involvement which the investigation will seek to establish. An act of total barbarity.

“I am in complete agreement with you when it comes to that final sentence”, continues Van Reybrouck. He adds: “Your term ‘act of war’ is extremely tendentious, even if that bellicose rhetoric has been shamelessly adopted by Mark Rutte in the Netherlands and Jan Jambon in Belgium. In your attempt to allay the fears of the nation, you have risked making the world less safe. In your attempt to speak out forcefully, you have shown weakness.”

“You fell for it”, concludes Van Reybrouck, “because you felt rowdies like Nicolas Sarkozy and Marine Le Pen breathing down you neck. […] You fell for it, because you handed over precisely what the terrorists were hoping for: a declaration of war. You gladly accepted their invitation to jihad. With your attempt at a firm reaction you are running a gigantic risk of allowing the spiral of violence to escalate even further. That seems less than wise to me”.

In addition to Flemish and French versions, Reybrouck posted his open letter to the French president on Facebook in English translation.

Also on Facebook, American historian Timothy Snyder reflects on what would be a really sensible and surprising response to the attacks in Paris: “After terror, during grief, figure out what the killers sought to provoke, and do something else.”

Fredrik Sonck, former editor at Finnish Eurozine partner Ny Tid, observes: “It’s hardly a coincidence that Paris has been hit two times in less than 12 months.” Sonck, now at the Helsinki newspaper Hufvudstadsbladet, continues

In the eighteenth century, Paris was the cradle of European Enlightenment, when the Church’s hegemonic power over the minds of free men was first seriously challenged, as was the hegemonic power of authoritarian rulers over the bodies of their subjects. The political and cultural consequences of the Enlightenment are immense. It’s one of the most precious achievements of Europe. This continent has to answer for much blood and oppression – inside it’s borders, and outside; there are many reasons to be ashamed. But this is not one of them.

The idea of freedom, equality and fraternity comes from Paris. But, writes Sonck, there are those who hate freedom, and are prepared to die to fight it. Islamist terrorists, for example, “who attack satire magazines, rock concerts and just ordinary people all over the world”.

And there are those who hate equality, whose hate is just as deep and who are just as ready to die and kill for their cause. Among those are right-wing extremists, “who burn down refugee camps, execute young social democrats and think that the value of a man depends on the colour of his skin.”

But the rest of us, concludes Sonck, “must never forget that third word in the slogan of the French Revolution, which reminds us of what we have in common: that we always, after all, are connected in this fraternity.”

Writing in Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter, Eurozine contributor Stefan Jonsson makes a similar analysis. “Fascism has landed in the middle of Europe”, he notes. On one side there are the white race warriors, such as Anders Behring Breivik, on the other the Islamist fanatics. “In between, on open sea and along the highways, there is a multitude of people who flee from conflict, people who refuse to become soldiers and victims in all these wars. […] The best thing Europe can do to protect its values is to defend the right to asylum and open up safe routes and cities of refuge.”

Jonsson concludes with a question: “Can we keep the situation in next few years from turning into a shoot-out between Behring Breivik’s race warriors and the jihadists of the Islamic State? Can we build societies instead of destroying them?”

As the new Polish government, in the person of the Minister for European Affairs, Konrad Szymanski, immediately took advantage of the attacks in Paris in order to denounce the European Union’s agreement on the distribution of refugees, Slawomir Sierakowski drew attention in Krytyka Polityczna to the Central European context: “Nationalists and other haters who are taking advantage of the refugee crisis in order to further their politics of fear will now attempt to convince Polish, Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian voters that they now have empirical justification for their views”. “Now more than ever”, concludes Sierakowski, “it is important to stress that refugees are victims of terrorism, not its source”.

In Res Publica Nowa (Poland), Anna Wójcik encourages both Polish and European commentators in the mainstream press to expand their horizons: “If, in following our hearts, we decide to express solidarity with Paris, then let’s also find space for solidarity with Beirut. Let’s do so, even if we are not necessarily following our hearts, but following reason. For we will never come close to understanding global events – such as terrorist attacks or ensuing mass migrations – if we filter information and compassion through a ‘European filter’.”

Meanwhile, Kenan Malik insists that “we should be wary of seeing these attacks as a response, however perverted, to French, or western, foreign policy. […] What the terrorists despised, what they tried to eliminate, were ordinary people, drinking, eating, laughing, mixing. That is what they hated – not so much the French state as the values of diversity and pluralism”.

“Terrorists often claim a political motive for their attacks”, Malik continues. “Commentators often try to rationalize such acts, suggesting that they are the inevitable result of a sense of injustice created by western foreign policy or by anti-Muslim attitudes in the West. Yet most attacks have been not on political targets, but on cafes or trains or mosques. Such attacks are not about making a political point, or achieving a political goal – as were, for instance, IRA bombings in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s – but are expressions of nihilistic savagery, the aim of which is solely to create fear. This is not terrorism with a political aim, but terror as an end in itself.”

As for building societies in the face of the threat of terrorism, following a rigorous critique of British multiculturalist and French assimilationist approaches, Malik suggests

An ideal policy would marry the beneficial aspects of the two approaches – celebrating diversity while treating everyone as citizens, rather than as simply belonging to particular communities. In practice, though, Britain and France have both institutionalized the more damaging features – Britain placing minorities into ethnic and cultural boxes, France attempting to create a common identity by treating those of North African origin as the Other. The consequence has been that in both Britain and France societies have become more fractured and tribal. And in both nations a space has been opened up for Islamism to grow.

In the German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Claus Leggewie elaborates on remarks first made in interview with the German radio station Deutschlandfunk Kultur. Leggewie writes: “IS would score an important success if Europe gave in under the force of the attacks and subsequent fears and re-erected internal borders. And if member states stop letting in the refugees, many of whom are of course Muslims, who wish to escape the tyranny of Al Qaeda and IS. It is still the refugees who are hardest hit by the terror.” Leggewie was in Paris as the terrorists struck, preparing for next month’s UN Climate Conference. But “while everyone wants to talk about climate, IS wages war”.

Published 17 November 2015

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The defence of democracy in France must continue to be a republican discourse, not one of libertarian nationalism. Critics of ‘Islamo-leftism’ engage in the very same process of blame-shifting that they accuse their opponents of – sometimes rightly.

From anti-vaxxers to terrorists, people often look for hidden causes which match the magnitude of the collapse they are facing. Uncertainty and public distrust are fertile ground for conspiracy theories. When used to legitimize violence, however, such narratives are more a strategy than psychopathology.