The Riace model

Immigration surges and regional depopulation can cause crises for the communities affected. Yet in the small town of Riace in southern Italy, these challenges are being met simultaneously. The ‘Riace model’ opens up a better future for crisis-struck regions, explains Olav Fumarola Unsgaard.

Typically, a busload of passengers in southern Italy comprises a lot of pensioners, some children and a scattering of middle-aged women. Everybody else drives a car. Not so in Riace, however. Although many cycle, the buses are almost full. The man in the seat next to mine is on his way to the town hall to get a document signed and, still more importantly, stamped. The ins and outs of his errand seem a little unclear but, to validate a payout of some sort, the right official stamp is apparently essential. At the bus stop in Riace, a township in southern Italy, we get ourselves glasses of cold, milky coffee and drink it in the shade. Nothing moves in the street. The town hall is next door to the station. The Italian tricolour is raised at the entrance but its red strip has blown away, making it look more like an Algerian or Nigerian flag.

The Olivetti computer on the oversized desk has a coating of brown dust. I ask around for the whereabouts of the mayor, Domenico Lucano, by now a legendary figure. Lucano could have found, in one unexpected move, the solution to two of the greatest challenges humankind faces at present: increased migration and regional depopulation. Visitations by journalists from distant places, news reports in at least ten different languages, invitations to address conferences and receptions for delegations of civil servants from Brussels – all this confirms the widespread belief that his approach, or the ‘Riace model’, could halt the steep decline in population levels in many European regions by resettling them with new inhabitants. Settlements for migrants, for people on the run: this sounds intuitively like a win-win deal. A house that stands empty is handed over to a refugee. Could it be that simple?

How the story began

The eastern coast of Calabria has been the gateway to Greece for thousands of years; if, like Odysseus, you were to sail your boat westwards from Greece’s Ionian Islands, you would end up in Calabria. In the summer of 1998, a boat left mainland Greece in bad weather and rough seas and ended up, a lot the worse for wear, at the town of Soverato, some forty kilometres north of Riace. There were 218 people on board: men, women and children, all Kurdish refugees, most of them from northern Iraq. At first, several coastal towns chipped in and helped by offering the new arrivals food and lodgings, but Riace took on the challenge with particular seriousness. The citizens and the mayor were united in seeing this as their joint cause.

Image: Olav Fumarola Unsgaard

‘We shared a dream of a town based on the values of our native culture. A culture of hospitality, of openness’, Lucano was quoted as saying in an interview for the Italian daily Corriere della Sera. At the time, the town was desperately run down: ‘Houses had been abandoned and stood empty, the local economy was paralysed.’

The movement of people away from Riace did not start with the closure of a factory, because modernization, let alone industrialization, never truly reached this part of Italy. By the end of World War II, when the town should have progressed from being a feudal farming community to become part of the new, post-war Italy, Riace entered a crisis. The number of inhabitants fell from almost 2500 to 400. Old folk stayed while the younger ones left, typically for the industrial cities in the north, like Milano and Turin, but also to northern Europe or to Australia and North America.

‘Do you like living here in Riace?’ I ask.

‘There isn’t much going on around here. Still, it’s better than the refugee camp I was in. Very crowded it was, far too many people in far too small a space.’

‘Where was that camp?’

‘Somewhere in Calabria. I was there for just eight days. Then they called out my name and told me I was going to Riace.’

‘Did you have a choice about where to go?’

‘None.’

We are talking in the shade of a sun umbrella in Café Agora in Riace Marina, near the country road between Catanzaro and Reggio Calabria. We drink quite a lot of water and have ordered coffees. Heavy trucks, many vespas and topolinos – the old Fiat 500s – keep passing on the road. I am speaking with Robbie from Gambia and Emmanuel from Mali. Their circle of friends includes migrants from Nigeria and Senegal and practically all the rest of West Africa. The office of the EU-funded integration project Oltre Lampedusa is located in a basement on a backstreet. On the office door, someone has pinned up a drawing of a paper boat garlanded with flowers with a quote from Mother Teresa below the boat. Some months ago, the association offered a beginners’ course in Italian but now the staff are focused on helping with practical things such as medical appointments, problems with finding somewhere to live, benefit payments and legal aid applications. Like most people with temporary residence permits, Robbie and Emmanuel live in “lower” Riace on the coast. Robbie takes me to his house but won’t let me have a look inside – too untidy, he says and adds that there is no proper space for anything. The landlady packs too many people into one room. He has pointed this out to her many times but she is not interested and doesn’t listen.

The town of Riace comes in two parts: Riace Marina on the coast of the Ionian Sea, and, eight kilometres higher up on the mountains, Riace Superiore, the main part of the township, which started out as a walled fortress. This region of Calabria was originally part of ancient Greece and has been populated ever since. Military strategy demanded defensive measures against attacks by occupying armies or bands of pirates roaming the coastal waters. Nowadays, for all its wonderful views, its location is more of a curse than a blessing. There are villas along the road but most of the buildings are deserted farm houses with caved-in roofs. More than anything, the landscape looks like stony desert, dry and almost devoid of vegetation.

Domenico Lucano was born in the town but took the first chance he had to leave for the north. He studied and also became a political activist, joining leftist extra-parliamentary organizations such as Lotta Continua or “Continuous Struggle” and, while it was part of the scene, Autonomia Operaia – an organization promoting regional autonomy. After several years in the north, the ex-schoolteacher grew homesick and returned to Riace. Since 1995, when he was elected on a non-party ticket, he has had the run of the town hall.

From aid to employment: A project for controlling the job market

‘Soon after the arrival of the Kurds, we organized a council – an association’, Lucano told the Corriere della Sera. They wrote applications for support and set up a kind of think-tank. How to deal with housing and sort out property ownerships was one of their most important tasks. Despite being abandoned, the houses could not be put to any use without the owner’s consent – no one could move in and repair work could not begin. However, finding the owners turned out not to be a major problem in this small community. In some cases, families could move in immediately, but sometimes the houses needed extensive renovations. Project funding was forthcoming so that the new on-site workforce could start to repair the tumbledown stone buildings.

Even so, compared with other towns and cities in southern Italy, Riace is still in bad shape, rather like an earthquake-damaged town that has recently been roughly restored, like Calitri: reinforcement bars protrude from cracked concrete, roof tiles have blown away and walls tumbled down. One of the maps shows a quarter called “Vilaggio Globale” – the global village. I find a house with the name painted on a sign on its front wall. It looks like a child’s scrawl. I enter a small workshop where a few women are seated, bent over their sewing. They come from Afghanistan but are now permanent residents in Riace. They tell me in an uncertain mixture of English, Italian and body language about the project that employs them. They sew and weave using older Italian techniques mixed with traditional Afghani handicraft, and create angels made of textiles as well as wall hangings and scarves. Business is slow because they have so few customers. Dotted around the old town, there are several other similar workshops, all of them financed through project funding. The workshops are just about the only business activities I come across, with a few others such as a partly shut-down shop selling souvenirs and the odd, corner store and other service providers.

The finance for the project-funded activities comes from several sources: the EU, the region of Calabria, left-of-centre charities such as ARCI (Associazione Ricreativa Culturale Italiana) and a handful of smaller associations set up to counter the influence of the mafia. Since the arrival of the first boatload of Kurds in 1998, Riace has received about 1,000 refugees annually. Some have stayed relatively briefly before moving off northwards. Bahram Acar, who was among the first group of Kurds, is one of those who remained. He told Corriere della Sera: ‘In Riace, I had found a place where I felt at home. The mountains remind me of Kurdistan. So, we decided to stay here.’

The task of transforming the town has become better organized over time. Work opportunities are distributed across a range of “laboratories”, or workshops. New arrivals can choose, with their previous skills and interests in mind, to go in for pottery, glass making, carpentry, cookery, weaving or sewing. The products are sold to Fair Trade outlets or markets, or consumed in the restaurant Dona Rosa. In addition to the migrant workforce, some 60 locals from Riace are employed on the projects to serve as supervisors and support workers.

On the day that I arrive in Riace, Lucano is unavailable, away somewhere or possibly in a meeting. Whatever it is, I cannot get past his stern secretary who, more than anything, seems amazed that an outsider has managed to gain entry into this beautifully cool building of pale stone. I pick up a handful of sun-bleached tourist leaflets and a few postcards, and set out to see the town instead.

After a while, I run into Amad. He tells me about how he escaped from Pakistan and ended up in Riace. He and his family have recently been granted permanent residence permits. They like it here and intend to settle in Riace. Amad’s orange overalls signify that he is employed in the environmental service sector. His wife is at home with their children but, off and on, she goes to work as a weaver in a laboratory. Amad, who speaks excellent English, tells me that their eldest child is due to start school soon. His monthly earnings are about 600 euros for four to six hours work per day. He has joined a workers’ cooperative charged with jobs such as street cleaning and park maintenance. The Italian bureaucracy handles migration issues, including applications for asylum and permanent rights of residence. And its mills grind slowly. The fundamental principle is that each application is considered individually but the applicant’s country of origin determines how it is processed. Everyone I speak to in the town agrees that people from war zones get priority treatment; these areas include Syria, Somalia, Sudan and regions of Iraq, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Asylum seekers and refugees from other troubled regions face a very uncertain time ahead. Amad and his family received their permits quickly but that actually translates as one-and-a-half years of waiting. Once established, their lives in Riace changed markedly: they were allowed to apply for work with one of the town’s many projects. Despite the state supported incomes, their daily labour really does make a difference. In most cases, people get jobs that need doing, though the local demand for textile angels and wall hangings seems rather less than expected. Above all, Amad and his family are happy to live in a peaceful place where their children can go to school, learn Italian and plan for the future. Being inside the system is of crucial importance, here as elsewhere in Europe. To possess the right documents, especially the residential permit, proves that you have the right to lead a normal life in the place where you have made your new home.

This particular family, unlike many others I have met, has no intention of moving on and going to the cities of northern Italy or, further still, to Germany or Scandinavia. In Riace, the narratives in circulation include beautiful tales of how, in these northern countries, living is easy and good even for the “paperless”. Some, like Robbie and Emmanuel, are sceptical and even self-critical: in Gambia and Mali, the stories told about life in Europe have turned out to be exaggerated, to put it mildly. Could the same also be true of the alleged dolce vita in the north?

The Lampedusa period

‘The boat was sinking. We bailed out using mugs and glasses. I didn’t know if I’d survive. Anyway, I fainted. I know that for sure. And woke up in a hospital bed. There were white people everywhere in the room. That’s how I knew this was Italy. I have now been here for two years and four days’.

Robbie arrived in Italy on 19 July in 2014. In the history of present-day migration to Europe, that date falls within “the Lampedusa period” when, for large numbers of migrants, the route to Europe went via Libya and ended on Lampedusa, the southernmost Italian island.

On 3 October 2013, a boat sank a few kilometres from the island: 366 people died and 155 were saved. The event alerted Europe and forced its leaders to respond. ‘After Lampedusa, we cannot continue as we were’, was one official reaction, this time from Cecilia Malmström, then the EU Commissioner for Refugees. Major decisions were taken to channel more money to Frontex, EU’s border security agency (European Border and Coast Guard Agency) and assist Italy with funding for reception facilities. The task forces patrolling the Mediterranean were improved and also reinforced by the Italian air and naval operation Mare Nostrum (followed in 2014-16 by Frontex’s Operation Triton). Lives were saved, Robbie’s life among many others. Even so, it became clear as early as autumn 2013 that the EU seemed incapable of coordinating anything more sustained than interventions in acute situations. Malmström’s most important recommendation for the longer term was for the European nations to agree on quotas for refugees, introducing “humanitarian visas” and establishing a timetable for legal travel to Europe for migrants. Since then, much has happened.

During the summer of 2014, those who set out on the dangerous sea crossing from Libya could at least hope to be rescued by patrol boats, should their craft start to sink. On the island, the reception camps had been upgraded and the charities were in place to provide help.

A year later, everything had changed again. The new situation radically affected Robbie’s chances and those of many who were with him. The “Lampedusa migrants” carried on risking the deadly transit at about the same rate as before but the world’s attention now focused on the eastern Mediterranean. The shift was due to the death of Alan Kurdi, a Kurdish child from Kobane in Syria, who drowned on 2 September 2015. His mother Rehan and brother Ghalib shared his fate but his father Abdullah survived. The weeks following the publication of the photographs of Alan’s lifeless body were extraordinary. The words on everyone’s lips were migration, flight and solidarity. Now, the death toll on the Mediterranean had been given a face. Idealistic support missions for newly arrived refugees were organized all over the continent – until, a few months later, the whole thing came to an end. Europe had decided it needed “breathing space”, a process that had already begun with Hungary closing its borders on the 15 September. After agreement between the EU and Turkey had been reached on 18 March 2016, the Balkan route via Turkey and Greece and through the northern Balkan countries was also closed.

Europe’s “breathing space” has had little effect on Italy. As with anywhere along the Mediterranean, concrete reality matters rather more than the abstract principles of European migration policies. During 2016, migration into Italy was higher than in the previous year: by the end of December 2016, a total of 178,764 persons had arrived. The new arrivals came on top of the 158,000 refugees already installed in various temporary facilities, camps and lodgings. Many want to move on but can’t get out from where they have been placed. The system for distributing refugees across the EU nations has run aground. So far, only 1,158 people have been helped to leave Italy. France and Switzerland have closed their borders and, as a direct result, the border towns Ventimiglia near Genoa and San Giovanni on the shore of Lake Como are crowded with refugees who have been stopped on their way northwards. The situation in Italy differs from other countries in Europe in that most of the migrants come from West Africa, Eritrea and Sudan rather than from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. Their chances of being allowed to stay in an increasingly isolationist Europe are vanishingly small. Those who are already in Italy, for instance in Riace, exist in a limbo: they have a temporary residential permit, a roof over their heads and a small daily pay-out but hardly any hope of better days to come.

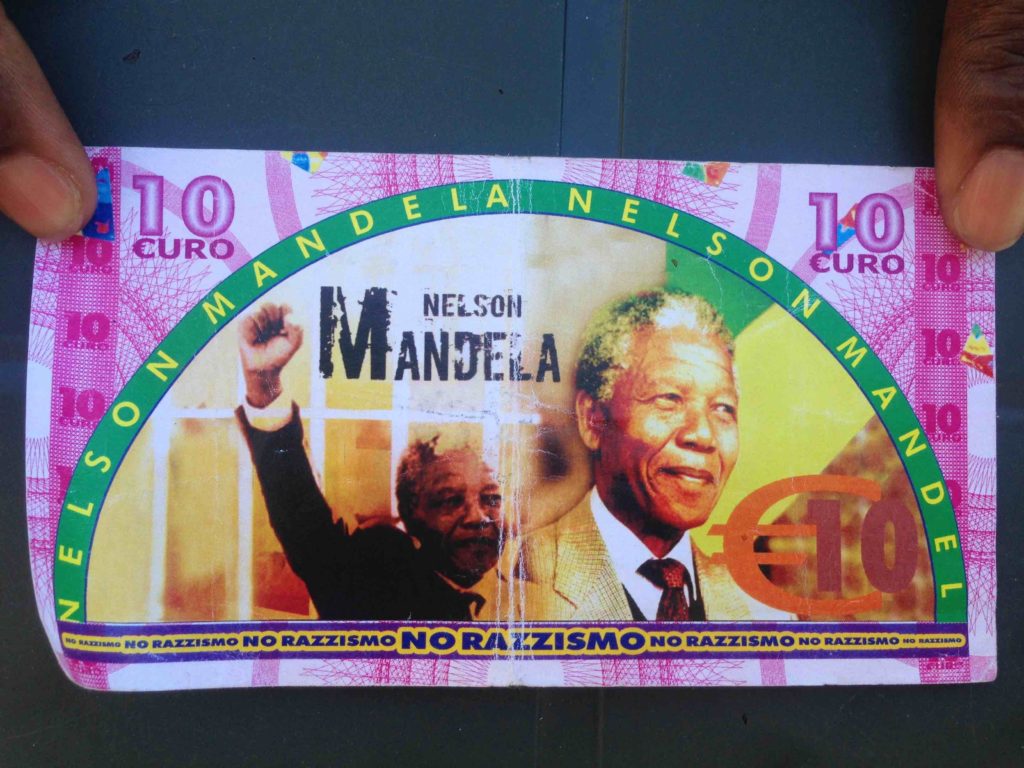

Robbie, Emmanuel and the others receive half their benefits in cash (around 150 euros per month) and the rest in local vouchers – a kind of cheque that is valid only within the municipality. ‘We call the vouchers “bonuses” or Mandela bills. They have the face of Nelson Mandela on one side. They are good in some shops, like Conad the grocers for instance and the place next door to the IT shop which will sell you bits of grilled chicken. I bought my mobile phone with the bonus bills. But if I want to charge my SIM-card I have to go to the tobacconist’s. And they take only euros there. I phone home two or three times a week, that costs at least 10 euros every time. Sometimes, I have to choose between calling my people and buying chicken.’

Image: Olav Fumarola Unsgaard

The “Mandela currency” is one way of injecting money into the community and favouring the local shopkeepers. During my days in Riace, I encounter two very different versions of how the system works: while the shopkeepers seem positive about it, the migrants are consistently negative. Their complaint is mainly the exchange rate with euros, which they claim is fraudulent and often means that one Mandela is worth 50 cents rather than one euro. The town hall officials insist that they know of no such value manipulation.

The Riace model

In the summer of 2016, Lucano discusses his ideas about a potential “Riace model” in an interview with Attilo de Alberi for the magazine Lettera and speculates about how it might develop:

Lettera: ‘Have you ever thought of extending the reach of the project, for instance via the Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani?’1

Lucano: ‘Regardless of that list in the Fortune magazine, I am someone of no political significance. Real power resides with the ministers of state, the regional governors and politicians in general. […] I am content with who I am: the mayor of a town in Calabria. […] It’s true that what we’re doing here has become well known. On 26 April, the regional president of Tuscany, Enrico Rossi, and several mayors from Italian towns and cities will come here [to study what we are doing]. It is a first step on the road.’

Riace is rundown and very poor. The town’s economy was rescued by the migrants’ arrival: the projects generate jobs, the property rentals support individual families and the turnover in the local shops has grown. About 60 original inhabitants are employed on the projects. External money has been pouring into this small economy: the benefit payments represent the largest investment ever made in it. And, to top it all, mayor Lucano is now world famous. His brave stand and his insistence on telling us about it has meant that, among other things, he made the list of the 50 most important politicians in the world, drawn up by the business magazine Fortune. Celebrities from all over the place have visited Riace. One of them was the German film director Wim Wenders. The outcome of his visit was a short documentary called Il Volo, based on the arrival of the first Kurdish contingent. It turned out to be a pathetically poor effort, overemphatic and often ridiculous. But, never mind: Wenders is the seriously famous director of such immortal classics as The American Friend, Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire. Besides, he is Bono’s mate. Riace is no longer a rural backwater: these days, it is “on the map”.

Image: Olav Fumarola Unsgaard

This is a small European township, peripherally located in a sparsely populated area, whose one previous claim to fame was the ancient artefacts known as the Riace bronzes, and whose image in contemporary literature and film was simply as the place where the local mafia, the ’Ndrangheta, hides its kidnap victims in the underground caves. It has no links to the luxury tourism of the Amalfi coast or to Ryanair’s tin-hangar in Lamezia, endpoint for its cheap flights. Despite Calabria’s food, sunshine and fabulous beaches, the region remains impoverished. According to Eurostat, the unemployment rate for young people (15–24 years old) is 65.1 per cent, the next highest figure in Europe after Ceuta and Melilla, the Spanish enclaves in North Africa. The Italian national statistical agency puts the average per capita income in southern Italy at 17,200 euros per annum. In Sweden, for instance, the corresponding figure is 32,700 euros.

‘The state is to blame, not us. We live in misery, we’re broke. We have the sun and the mountains but no state provisions. We cannot do everything ourselves. There are no roads or railways here, no factories, nothing.’ This is Francesco speaking. He comes from the town Africo, some sixty kilometres further south and was quoted in a Newsweek reportage that, almost inevitably, focused on the mafia – not on the widespread poverty in the region, or on the failure to redistribute wealth between northern and southern Italy.

The flood of people who has been draining away from Riace since the end of World War II is still flowing, regardless of whether people are native born or have brand-new residential permits. Legambiente, an Italian environmental organization, published a glum report in the spring of 2016: the number of borderline ghost towns and villages in Italy has almost reached the 2,500 mark. In these depopulated places, the remaining residents tend to be the old and/or infirm who don’t want to leave or are physically incapable of moving out. Communities are taken to be at risk of dying out if one in seven inhabitants have left over the last 25 years. Narrowmindedness and intolerance, climate and religion and, of course, the mafia contribute to this development, but lack of work is the primary cause.

Riace in northern Europe

As in Italy, so in Sweden. Here, too, many communities have plenty of room but are short of inhabitants. The list of places with the highest intake of refugees relative to the number of settled residents is dominated by small towns in low-population areas: examples include Ljusnarsberg, Norberg, Laxå, Undrom and Lessebo. Just as in Riace, new guests suddenly fill youth hostels that would normally be deserted during colder times of year. External money is flowing in and turnover is growing in the local enterprises.

The municipality of Lessebo is located southeast of the much larger city of Växjö in the county of Småland, famous for growing and processing timber and for glass making. Lessebo has about 8,500 inhabitants. It comes first in the rank order of Småland towns that have accepted a large number of migrants over the last few years: the figure is now 3.46 refugees per 100 inhabitants. Here, the story is not of boats wrecked along the shores of the local Lake Rottnen: it is much more ur-Swedish. During the glass industry’s most expansive period, an early influx of Greek workers was followed by other nationalities caught up in the upheavals elsewhere in the world and the subsequent streams of migrants: Finns, Hungarians, Czechs, Chileans, Lebanese, Bosnians, Somalis, stateless Palestinians and, most recently, Syrians. There were a few dedicated lodging houses for refugees administered by what was once the Immigration Office. Since then, the housing of incomers has been managed by the Immigration Office’s new incarnation, the Swedish Migration Agency. The Agency rents flats owned by Lessebohus, the local authority’s property company. Most recently, private business has entered the market and various commercial buildings are rented out, such as Lessebo Inn, Motel Glassblower, the Bergdala pub-cum-backpacker’s hostel and Attendo Kosta’s “temporary industrial lodgings” (ABTs).

Carl-Axel Hallberg is responsible for the municipality’s refugee policies: ‘We have received at least 500 people in the last few years. Our local schools have had to make room for 300 additional pupils, exceeding the forecast of two years ago. Back then, the talk was all about how one of the schools might have to close. Instead, we are forced to build new classroom blocks to cope with the numbers.’

‘Do the migrants stay here’, I ask, ‘even after they’ve been given full residential permits?’

‘Yes, on the whole. We try to avoid creating bureaucratic obstructions. And also to look for opportunities rather than problems. The most important factor is employment. We support job creation in the public sector, so-called New Start jobs with employers such as Lessebohus and our schools. Quite a few people work for the schools as language assistants, for instance, or as classroom resources generally. There are still some local enterprises but not that many. The national road 25 to Växjö and Kalmar passes through the town and that’s an advantage. And we have some retail trade.’

The local authority attempts to support the new arrivals across a wide range of services but the settled inhabitants are asked to help actively. There is training on offer for people who want to take up advocacy or to become a contact family or foster home. The library runs language cafés and a project called “Language Buddy”. Freed-up living space is registered at regional level, and business people who are keen to help are told to notify the job centre. One example of local enterprise is the joint enterprise of two women, Helena Lundholm and Maha Haddad (Haddad arrived from Syria four years ago), who run a successful project based on home visits to refugee lodgings. The visits were initially aimed at understanding the different needs. Lundholm and Haddad collected and distributed donated clothing. Later, they expanded and began to provide courses and excursions as well as help with practical issues. Some of the large charitable organizations such as the Red Cross, the Philadelphia Church and ABF (Workers Educational Association) now run projects along similar lines with a wide range of support activities, from courses in Swedish to distribution of clothing and family get-togethers.

Despite some protests against the way lodgings are made available and the usual chorus of agonized complaints and digital whining, as well as the lies published by alt-right media like Avpixlat and the neo-Nazi Nordfront, the story of Lessebo and other places, such as Hovmantorp, Kosta and Skruv, tells of a Sweden characterized by local societies, churches and membership of the large, national charities. The educationalist Peter Sand from the Hovmantorp branch of ABF tells me, in his singing dialect: ‘We’ve done as much as we can. We are study-oriented so we offer courses in social structure and everyday Swedish. We use Arabic and Swedish to inform people about things like allemansrätten [the Swedish law ensuring “freedom to roam”] and the theory part of the driving licence requirements. And we instruct people about Swedish employment regulations concerning, for instance, work time limits and time keeping, workplace agreements – workers’ rights and obligations.’

Depopulated areas and the future

Does the working model operating in Riace and Lessebo demonstrate how fading, sparsely populated townships can spring back into life? The simple answer is: yes, it does. Both localities need outside investment but they also need people who move into the abandoned villas, rented flats and empty hostels. When there are people, the welfare system can set to work and the schools can be kept open. There are many similarities between Riace, Lessebo and other reported examples such as Undrom in county Ångermanland in Sweden.2 Receiving refugees opens up a route to a better future for crisis-struck European regions.

However, it should not be thought of as a “quick fix” for deep-seated structural problems. People leave towns and villages because job opportunities are drying up. The Swedish model, which relies on an extensive welfare state, is capable of generating more jobs by applying the basic formula that those who are already in the place can help new arrivals. In Italy, the reach of state welfare is more limited. Services such as childcare and home carers are traditionally carried out within the family. It follows that the welfare sector does not automatically grow in line with increases in population. Riace is very poor compared to Lessebo and Undrom, even if one includes the black economy that, according to official figures issued by Italy’s central bank, amounts to about 20 per cent of the country’s GDP. You are on your own, regardless of whether you are a recently arrived migrant or an Italian citizen. All you can do is put your trust in relatives, if you have any.

What is singular about the case of Riace, however, is not the harsh present. It is that Robbie, Emmanuel and other West Africans can’t move on. They are stuck in a place where few people with the right documents want to stay, and where the economy (official and black alike) is shaky, a place where the future depends on concepts such as “being on the map”. Riace’s unique feature is that it has shown the will to formulate an alternative that entails standing up for the rights of refugees and offers hope for depopulated areas in an increasingly closed Europe marked by resignation. Local politicians in small towns have more options than to promote local gastronomy, culture or sports facilities and can instead chose to combine high ideals with economic reality. It is an alternative that allows the forces of increasing migration and globalization to be mobilized for the greater good.

Sources

Interviews

The interviews in Riace took place in July 2016 [Robbie and Emmanuel are not real names].

Carl-Axel Hallberg and Peter Sand were interviewed at the end of November 2016.

Newspapers and magazines

Dagens Nyheter, “Bortom Lampedusa kan vi inte fortsätta som vanligt” [After Lampedusa we cannot carry on as usual], 23 October 2013

Italy Europe 24, “Per capita GDP: The abyss between North and South”, 9 February 2015

Newsweek, “In Italy’s poorest town, there’s little to do but join the mafia”, 15 September 2015

Corriere della Sera “Benvenuti a Riace, dove i migranti hanno risollevato l’economia)” [Welcome to Riace where the migrants are resurrecting the economy], 16 September 2015

Lokaltidningen Växjö, “Flyktinghjälp i Hovmantorp fortsätter över 2016” [Refugee aid in Hovmantorp continues throughout 2016], 1 December 2015

Dagens Nyheter “Trängda kommuner fortsätter ta emot flest flyktingar” [Local authorities under pressure continue to receive refugees], 1 April 2016

Lettera 43 “Così i migranti hanno cambiato Riace” [How migrants have changed Riace], 15 May 2016

The Telegraph “A third of Italy’s villages at risk of depopulation and abandonment”, 1 June 2016

Other

All figures quoted for migrations and migratory routes are drawn from the website of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); it is updated on a weekly basis.

I recommend Tomas Lappalainen’s book about the Calabrian mafia: ’Ndrangheta – en bok om maffian i Kalabrien (Fischer, 2010) which, despite the title, contains much cultural and historical reportage.

The Associazione Nazionale Comuni Italiani or ANCI is the Italian association of local authorities.

Cf. Ida Forsgren’s piece in Arena 5/2016.

Published 13 April 2017

Original in Swedish

Translated by

Anna Paterson

First published by Glänta 3-4/2016 (Swedish version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Glänta © Olav Fumarola Unsgaard / Glänta / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Once referring to natural resources and collectively managed land, the notion of the ‘commons’ has expanded across cultural, scientific and digital realms. Can commonality dodge the threat of capitalist exploitation and develop into an organizational principle for complex societies?

On making commons concrete

The Dutch Review of Books 2/2021

‘The Dutch Review of Books’ presents: the commons, vying for legitimacy between state and capitalism; the void of societal responsibility for #MeToo; and African oral traditions evident in rap music.