The reality of ‘never again’

COP26 lists collaboration as one of its main objectives. All views are seemingly welcome. And yet environmental justice, the law-making that should speak for Indigenous people, isn’t explicitly on the table. If laws and legal action remain static, based on corporate culpability after the fact to the exclusion of motive and context, how will future environmental plunder ever be avoided?

When Rio Tinto destroyed Juukan Gorge, which represented 46,000 years of culture and history for the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) peoples of the Pilbara in Western Australia, there were immediate ramifications and a flurry of activities from a range of actors. Many scholars wrote about the scale of the destruction, its impact on the PKKP peoples, and the broader consequences for Indigenous rights in Australia.1 The mining giant was compelled to think about dealing with the visible effects of its actions, which had put the sinister activities of settler-colony extractivism into the spotlight. For the rest of Australia and the world, it was a call for self-reflection to understand Indigenous heritage, and their cultural and spiritual relationships with the environment and the land.

The plant at the Brockman 4 mine in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Photo by Calistemon, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The destruction of Juukan Gorge disrupted the familiar abstractions and theorizations that are characteristic of environmental justice discourses. Rio Tinto’s action not only left a gaping wound on the land but it also exposed the violent nature of environmental injustices in settler states. The currently existing frameworks of environmental justice in general allow mining behemoths like Rio Tinto to act with impunity. But the ‘event’ of destruction – bookended as it was by the inadequacies of existing laws, the effective thwarting of any legal recourse, and the stinging indifference of the settler state towards providing a platform for effective Indigenous voice and self-determination – has to some extent prompted a re-examination of these framings.

Here, I will examine the many entanglements of environmental injustice that exist at the intersection of law, coloniality, Indigenous sovereignty and environmental harms. Just as the avoidance of corporate culpability is enmeshed within the complex structures of corporations, so an unwillingness to acknowledge responsibility for the depredations of colonialism is palpable within the economic, social and legal apparatuses of settler states. To think critically about Indigenous environmental justice is to undertake the task of disentangling the relations between these socio-legal and economic structures, in order to understand the extent of their complicity with and liability for the dispossession and erasure of Indigenous peoples; and such rethinking necessarily involves interrogating the reluctance of modern liberal states to face the questions of sovereignty, decoloniality and Land Back. Australia functions as a ground zero for this conversation because of the nature of its legal terrain: that is, it lacks any substantive protection for Indigenous rights, or any acknowledgment of historic and contemporary racialized state violence against Indigenous people.

But it is also the case that many countries that are not settler colonies but have imposed an extensive degree of internal colonization or Indigenous dispossession, in the interests of economic ‘development’, share similar features, and these offer further material for an analysis of environmental injustices carried out against Indigenous peoples. One can draw lessons from jurisdictions all around the world: in countries where there is no coherent protection of Indigenous rights; those where there is nominal recognition but without fundamental challenge to neo-extractivism; and even those that have token liberal constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights. All tell the same story of environmental and cultural destruction.

In places where the potential for significant political and economic transformation and/or systemic overhaul is not possible, it is imperative that social movements and juridical spaces begin to adopt a radical shift in their vocabulary and in their world-making practices. As part of this shift, understanding the role of courts in shaping the epistemology of Indigenous environmental justice is a vital task for radical environmental justice movements.

The aftermath of Juukan Gorge

The Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee established to look into the cause and consequences of the Juukan Gorge destruction, and its ramifications for the larger question of Indigenous heritage, submitted its interim report, ‘Never Again’, in December 2020. The report considers the huge number of submissions made by the Indigenous community in and out of Western Australia; and it also adequately captures the sense of loss, anguish, cultural and spiritual destruction and intergenerational trauma arising from Rio Tinto’s actions. To quote from the Chair, the Honourable Warren Enstch MP: ‘The Committee has made the point all the way through this inquiry that the destruction at Juukan Gorge has not just impacted on a small and discreet group of Traditional Owners in the middle of the Pilbara; it has robbed a significant piece of history from all Australians – from the world.’

The Chair concludes with a decisive ‘never again’, suggesting that the Juukan Gorge destruction was a lapse that shall never be allowed to recur. However, the interim report’s focus on Rio Tinto’s specific act, rather than its motives or context, begs the question of what the assertion ‘never again’ actually addresses. Is it a ‘never again’ to the logic of settler colonialism that desires the Indigenous subject to be erased? Is it a ‘never again’ to the extractive capitalism that rearranges economic and social life with the singular objective of accumulation of wealth? Is it an unequivocal desire to disrupt the collaboration between settler colonialism and capitalism, which sustain each other’s potential to leech off the planet’s life and resources to the point of extinction? It would, of course, be an incomplete analysis to attribute what happened at Juukan Gorge solely to the failings of the law, including on corporate accountability. Most obviously, Rio Tinto’s organisational hierarchy bears a heavy responsibility for its facilitation of the destruction. However, the weakness of existing legal protections, and the absence of avenues for recourse, suggest that similar events across Australia will continue to occur.

Indigenous cultural and environmental heritage and relations exist as expendables in a settler state – something which the interim report does not acknowledge. It also ignores the reality that corporate structures – which are deliberately designed to obscure – function very much in keeping with the economic ideology that underpins the sovereign state. The state and large-scale corporations share an outlook that functions to sustain oppressive social and economic relations while also keeping up the threadbare façade of nominal rights and constitutional protections. Thus mining companies often appear to endorse procedural forms of fairness towards Indigenous peoples, such as seeking a social license to operate and engaging in consultation with the land councils.2 The state enacts legal mechanisms that appear to offer protections. But these mechanisms and procedures are usually either easily circumvented or can be followed in ways that have little impact on extractive objectives.

In the Juukan Gorge case, permission to carry out the blast was granted under Section 18 of the Western Australia Aboriginal Heritage Act, 1972, which has no provision for consultation with traditional owners of the land. Nor does the Act have any provision for a review of the permission at a later stage should additional information regarding the site come to light. Yet it was only after Rio Tinto had obtained permission to blast that archaeologists discovered ancient artefacts and tools in the gorge that significantly increased its historical and cultural importance. Scholars have identified two key elements within the corporate structure of Rio Tinto that contributed to the fateful decision to destroy Juukan Gorge. First, the chain of command means that the decision-making process is apparently completely separate from any information that has been gathered regarding significant factors that might influence such decisions. Second, the primacy given to goals such as growth, innovation, corporate resources and human resources is missing when it comes to Indigenous matters. Indigenous relations are considered under the umbrella of ‘corporate relations’, which also takes care of external affairs, sustainability, brand, media, etc. This in itself strongly indicates that the top-ranking executive committee does not hold Indigenous affairs as close to their hearts as they do finance or investment. This organisational hierarchy means that the gravity of any issue will have petered out by the time the information from the bottom level reaches the executive that is responsible for decision-making.3

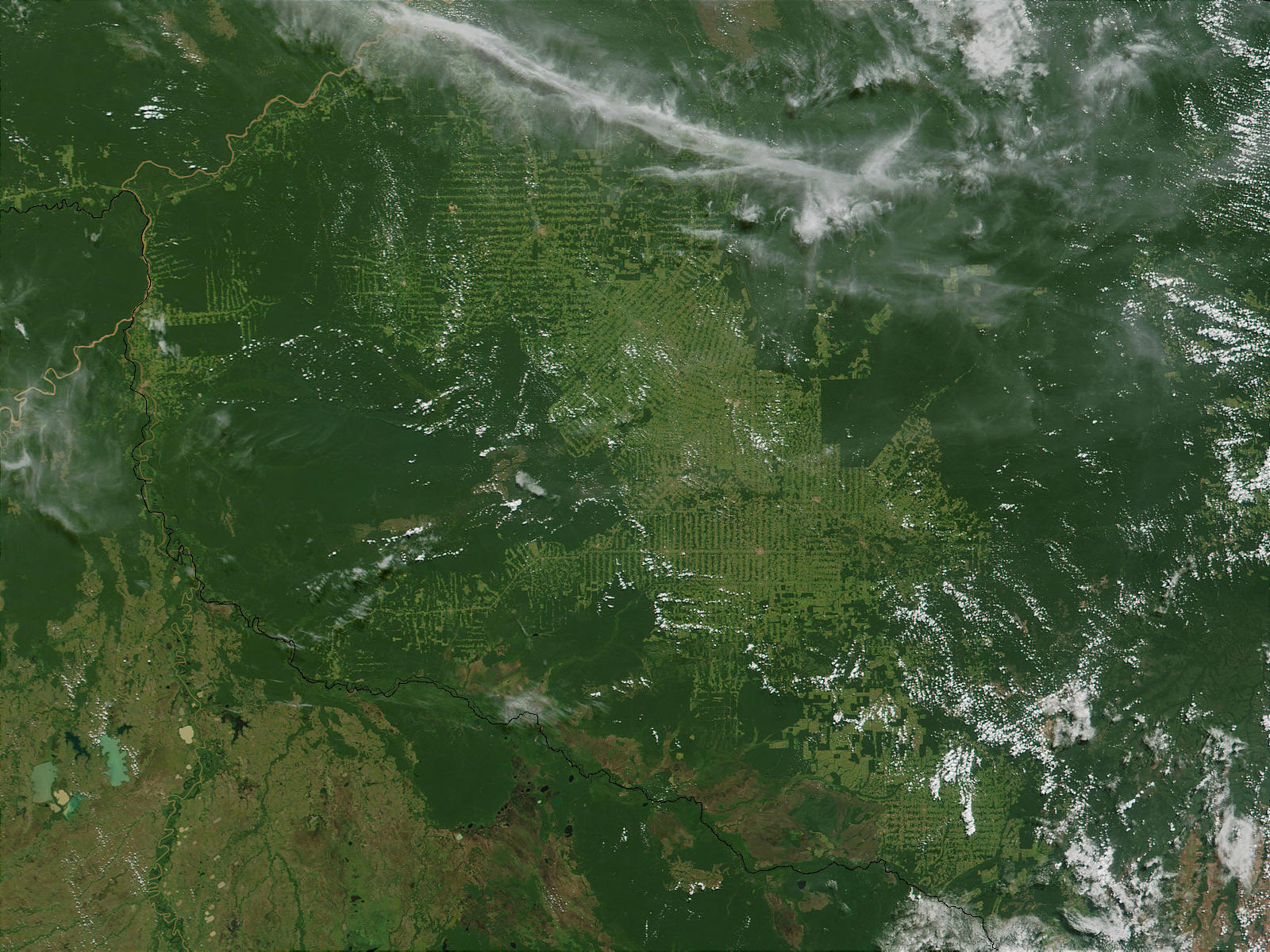

This true-color MODIS image of the Rondonia region of Brazil shows the massive deforestation underway in the south-central Amazon Basin. Photo by

Banco de Imágenes Geológicas / Ignacio Benvenuty Canbal from Flickr

Rio Tinto’s apologies after the event could not but appear vacuous when it came to be known that the corporate entity had already been assembling a team of lawyers before it carried out the explosion, in case the PKKP raised any legal objections or demanded an injunction against its planned destruction. One remains doubtful whether this was a question of information that did not reach the executive council, or whether perhaps there may have been some foresight lacking about the magnitude of public and shareholder outrage at the destruction of the site.

Even as the fallout from Juukan Gorge continues to evolve, Rio Tinto has secured permission to build the largest copper mine in the United States on the Apache sacred land of Oak Flats. Attempts to halt the mining project from going ahead there have been unsuccessful in the district court, but the community continues to resist within and outside juridical spaces.

Mining corporations may deploy different negotiation strategies with different communities. However, their innate disposition towards exploitation and erasure calls to mind Marx’s description of capital as something that ‘comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt’.4

The ‘rights-benefits’ trade-off

‘Aboriginal rights’ that the state has grudgingly recognized are often treated, in law and in political discourse, as something that can be counter-balanced by its citizens’ socio-economic interests. This seemed to be the case when the state government of Victoria, in Australia, chopped down the culturally significant Directions Tree as part of the controversial Western Highway upgrade, soon after the Juukan Gorge destruction. The ancient yellow box tree, situated in Western Victoria, held spiritual significance for the Djab Wurrung people, and its destruction inflicted great sorrow on a community that had been striving to prevent the desecration and destruction of its sacred trees for more than two and a half years. Even after the communities then achieved a measure of success in the Federal Court, when they managed to obtain an injunction against any further destruction, uncertainty over the fate of other trees continued: some of the sacred trees and sites around the region were still being destroyed after the injunction.5 Consequently, the First Nations have recently taken it upon themselves to crowdsource and buy the piece of private land on which another sacred tree stood. The paradox of buying back stolen land is not lost on anyone.

What is most striking here is the shifting of responsibility on to Indigenous communities to safeguard their heritage and protect their knowledge forms and cosmologies – and therefore resort to the familiar tropes of economic transaction.

A similar ruling in favour of corporate interests was seen in Talbott v Minister for the Environment, in which an application was made for the halting of the operations of the locally unpopular Shenhua coal mine on the grounds that it threatened Indigenous heritage.6 The court concluded that the minister had the right to trade off Aboriginal heritage sites in view of the alleged socio-economic benefits that would flow from the mine. Ironically, a couple of months later the New South Wales government shelled out $100 million to cancel the Shenhua coal mine – just in time for a by-election in the area. The government action put an end to the coal mine but not to some of the significant issues it raised. In a similar way to the saving of the Djab Wurrung heritage trees, the community’s success here is accidental. To benefit future movements and ensure the end of settler capitalism itself, the important question one must raise at this juncture is: does buying back land do anything to extinguish extraction as an activity or extractivism as a defining and organising logic of contemporary social and economic life?

The interim report of the Joint Standing Committee set up after Juukan encourages other mining giants of Australia, such as Fortescue Mining Group and BHP, to join the moratorium on future mining. But such a call ignores the fact that each of these corporations has a terrible track record when it comes to engaging with Indigenous issues – or to actively dispossessing them from their native title land and damaging their environment and heritage. While at the time of writing the full report is yet to be presented, the angst expressed in the interim report is somewhat undermined by their leaving issues of justice to be addressed through negotiation between the state and capital. What’s more, Senator Dean Smith has been allowed to register his ‘dissenting’ observations in the interim report. The senator argues that, while Rio Tinto must be sharply chastized for its actions, mining ventures should not attract our broad condemnation – contrary to the main observation of the Chair.7 This refusal to accept a broader context lays bare the nature of complicity between the settler state and extractive capitalism. Senator Smith’s desire to treat the incident as an exception, an anomaly within the sanctioned exploitation of extractivism, reminds us of the state’s role as a guardian and enabler of capitalism. Intricate political and economic arrangements such as these make the task of ‘locating injustices’ a difficult one.

The losses inflicted on Indigenous culture and the environment, and the decimation of people’s spiritual ways of life, cosmologies and epistemologies, are clear for all to see. Nevertheless, we are still left wondering how one remedies these losses, and who should shoulder the responsibility of recognition and reconciliation, especially given that the state is partisan. Indigenous dispossession and erasure cannot be comprehended or addressed within the spatial and temporal limits currently known to western epistemologies. In addition, it is impossible to separate recent acts of environmental harm from the past and present of stolen land, or the racism, discrimination and inequality that has been inflicted on Indigenous lives.

The regulation-busting logic of extraction

The operations of extractive capitalism exhibit the same patterns of violent extraction, racial capitalism and colonialism in other countries, even outside the settler nations. The resource-rich nations of the Global South in particular have been treated as a resource pool to be plundered. Needless to add, the empires of the past have shapeshifted to take the form of neoliberal apparatuses functioning alongside more benign-seeming modern liberal governments and operating according to a capitalist logic that governs life and death within the state. In countries where the land question is not so clearly apparent within the domestic extractive context, the environmental harms inflicted by unregulated extractivism overlap with conflicts over resources. While different classes and communities may be affected in different ways by relentless resource extraction, its impact on Indigenous communities is much greater in most countries, and not always visible. Even in places where there is discernible environmental and regulatory compliance by mining corporations, it is intrinsic to the operation of extractive capitalism to colonize land and disregard the plurality and diversity of the lives and knowledge forms of its local inhabitants. Lands where Indigenous people have lived since before the existence of modern states possess intricate networks of relationships and cosmologies. None of the regulations devised to fulfil a neoliberal model of procedural fairness can address the complexities of immanent relationships with the land and resources. As we have seen, Indigenous relationships with the environment tend to fall within the domain of negotiables in big mining projects, with no acknowledgement of their utter incommensurability.

Further, there is little room for understanding or re-configuring notions of Indigenous self-determination if there is no ability to participate, or to veto extractive projects. These limitations are tellingly manifest across the global South: oil extraction projects in Amazonian regions (Ecuador, Peru); copper mines in Bougainville (Papua New Guinea), which have been met with prolonged armed resistance; lithium mining defined by neo-extractivism in Bolivia; oil extraction projects in the Okavango Delta (Botswana) – and many more. The robotic developmental narrative overwhelms all other concerns and drowns out all the forces opposing the systemic erasure of Indigenous peoples’ ecological, territorial and cultural rights.

Extractivism in Ecuador

Oil pollution in the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador Photo by Julien Gomba, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ecuadorian Amazon has witnessed innumerable noxious enterprises, which operate with impunity and leave behind a trail of environmental destruction. Its Indigenous people have had little or no recourse or remedy in the face of these corporations’ constant oil spills, environmental pollution, contamination of water sources and destruction of local food sovereignty. They have had to battle against corporate multinational giants, and in some instances against the highly militarized state. And sometimes the battle itself has aggravated the social, economic and ecological injustices.

One instructive case here is the well-known battle between Chevron and US lawyer Steven Donziger, who represented 30,000 local people in a lawsuit seeking damages for the environmental destruction wrought by the company. Between 1964 and 1992, during its operations on the Lago Agrio oil field, Texaco dumped 16 billion gallons of toxic waste into Ecuadorian waterways, an activity that was carried out in collaboration with Ecuador’s national oil company, Petroecuador. In 2001, in the middle of the lawsuit over damages, Chevron bought Texaco, and argued that it was thereafter the responsibility of Texaco and Petroecuador to remedy any environmental pollution arising out of the operation. Nevertheless, after protracted litigation, the Ecuadorian court awarded an unprecedented $18 billion in compensation to the complainants. The appellate courts and Supreme Court then approved the verdict fully, though they reduced the amount of compensation. What followed was the unleashing of Chevron’s corporate might against Donziger through a series of counter cases in the US, the last of which resulted in a sentence of house arrest for alleged contempt of court. This is no more than Chevron had promised: it had stated early on in proceedings that the litigants would be drawn into a ‘lifetime of litigation’. Unlike Rio Tinto, Chevron has not faced any public scrutiny or experienced any ramification for its actions. Yet a recently revealed internal memo from Chevron has shown conclusively that the corporation has systematically undervalued human lives and the environment, through its constant prioritising of profits over every other concern. A company with a current market capitalisation of $228 billion remarked that spending an additional $4 million to line a pit and contain contamination was not ‘economical’. Because Chevron operates under the legal and political aegis of the richer nations of the Global North, it is able to wreak destruction in the South with no fear of local laws, while simultaneously persecuting those who oppose its violent extractive processes in the North.

Chevron is not the only villain of the piece, however. The Ecuadorian relationship with oil has always been violent and exploitative. The fact that Petroecuador is a national enterprise has by no means restrained extraction from the infliction of environmental injustices. Resource extraction is still continuing without adequate consultation, participation or consent from Indigenous communities; and Indigenous communities continue to bear the brunt of oil spills, and remain without reparation or remedy. While the Juukan Gorge made it into the mainstream news because of the great historical importance of the site, the ongoing devastation in Latin American nations due to operations to extract gold, lithium, oil and gas, amongst others, will have a massive impact on the generations to come. These extractive operations are not specific events capable of drawing attention, but a slow and sinister movement of capital that gnaws away at the food, water, health, medicinal knowledge and traditional hunting and fishing practices of Indigenous people – and is gradually undermining their whole ways of life.

Pre-trial barriers to justice

Resistance to extractive capitalism sometimes makes it into the courts, but results there are mixed. In some cases, whether or not a case should be allowed to make its way into the courts becomes a question of ‘ease of doing business’: countries are anxious to score well on this international measure of the ‘friendliness’ of local regulatory regimes to business. And there are often other procedural hurdles that prevent questions of environmental redress from being adjudicated. The result is that responsibility for decision-making is shifted to the arena of social and political negotiations, where the power imbalance between the parties concerned is acute. No country is an exception to these patterns of obstruction, and the Mount Polley litigation in Canada is a case in point.

Aerial view of the earthen dam at Mount Polley Mine in British Columbia that breached on August 4, 2014, sending contaminated water into nearby lakes. Photo by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Adam Voiland., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 2014, the Mount Polley dam in British Columbia – which was holding back a tailings pond at the Mount Polley mine above Quesnel Lake – collapsed, releasing around 24 million cubic metres of mine tailings into the lake. Toxins like arsenic, mercury, selenium, lead and copper, subsequently contaminated the lake, which was a source of drinking water and a significant habitat for sockeye salmon. This was one of the biggest dam disasters in Canada, and its effects are still being felt. Many First Nations along the river bank were affected. Their traditional fishing rights and water use rights were severely curtailed, and were possibly irreversibly harmed.

The Province failed to initiate a prosecution against Mount Polley Mining Corporation under the Mines Act, 1996, or the Environmental Management Act, 2003. However, the former chief of Xat’sull First Nation initiated a private prosecution for the environmental damage and damage caused to traditional rights as a result of the dam collapse, claiming compensation and remediation. Instead of pursuing the case, the BC prosecution service first took over the private prosecution and then decided to abandon it because the prosecution did not meet the charge assessment standards. These charge assessment guidelines denote whether or not prosecution is adequately in the public interest. The prosecution service failed to provide any reason why Xat’sull First Nation’s prosecution failed the test. Abstract government statements of commitment to environmental protection, and reconciliation with Indigenous people as a meaningful element within such a commitment, too often mean nothing when it comes to specific cases and the question of legal redress.

This kind of extractive violence takes material and tangible forms, but Indigenous dispossession can also occur through agencies that are projected as more pro-environmental. Unless there is a categorical acknowledgement of the centrality of Indigenous sovereignty to the environmental justice question, what appear to be greener alternatives can also reproduce colonial and racist practices. Examples of this include geoengineering experiments in Sweden that affect Sámi territory, and wind energy projects in northern Colombia and Southern Mexico.8 Clean energy and development are certainly an alternative to fossil-based energy and extraction, but it is by no means clear that they offer an alternative to the kinds of capital accumulation that engulf Indigenous lives. There can be no justice if the technical fix for climate change, or green energy alternatives, are steeped in practices of racial discrimination, Indigenous erasure, and entrenching white privilege and supremacy.

Can courts play a more promising role?

The entangled nature of the social and the political spheres, and their cosy relationship with extractive and colonial capitalism, means that we often focus our efforts in the pursuit of justice on the juridical sphere. But this does not imply any absolution for the law. The function of laws in capitalist economies has in general been to facilitate and endorse structures for accumulation and expropriation. This foundational function within capitalism also extends to settler colonies, where the erasure of existing relationships with the land, in order to render them ‘property’, falls within the remit of the law. Nonetheless, there is more to the juridical spaces and justice discourses than the existence of settler laws. The juridical space is the only one that stands within the complex network of colonial and extractive structures while simultaneously enabling effective resistance to those same structures.

In addition, Indigenous communities have had a diverse range of encounters and engagements with the state when there have been opportunities for autonomous decision-making; and courts feature prominently in cases where environmental litigation has been used to encourage recognition of Indigenous cultural and environmental claims, and the claim to self-determination and preservation of indigeneity. The nature of the claims made, and the likelihood of their success, depend on the legal cultures and histories of the jurisdictions within which they are pursued. For instance, Canada, although known for its constitutional recognition of First Nations and many existing treaties, has not been receptive to claims that fall outside of treaty rights in Indigenous environmental litigation.9 In the spirit of its ongoing settler-colonial project, Canadian courts tend to fall back on the existing legal framework and its limited range of remedies to resolve the issues that are brought before them – a rigidity in interpretation that is not merely an attribute of the superior courts but can be found across the hierarchy.

There are less disappointing outcomes elsewhere, however, especially in places where Indigenous movements have diversified their tactics to constantly engage the courts, in the absence of adequate mechanisms of redress through political channels. While the diversity in international patterns of progressive jurisprudence can seem overwhelming, there have been cases across the globe that have shown that courts are beginning to consider themselves as needing to be responsive to the pressures of the Anthropocene. The specialist environmental court of Australia, for instance, is often in the spotlight for its radical pro-climate stance. It is arguable that the absence of strong constitutional environmental protection, and the fragmentary nature of Indigenous rights protection, is itself a primary driving force behind the devising of new approaches to radical environmental jurisprudence.

More promising trends are also emerging from the countries of the Global South that have been historically looted for their resources. The legal and political structures in these nations have been mostly designed to uphold the proprietary rights of the capitalist classes. But recently, for example, the Supreme Court of Panama held that the Indigenous communities living within its jurisdiction had the right to secure their territorial rights, have their reserves and traditional lands demarcated, and demand that the state consolidate their land and cultural rights. It also held that the returning of traditional land to Indigenous guardianship is in the best interest of the environment. This decision came in the wake of a series of turnarounds by the Panama government after Panama’s legislature had passed a law to recognize the traditional lands of Naso Tjër Di Comarca. In addition, the judgment mirrors the observations made in the recent joint report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (FILAC), which emphasizes that Indigenous guardianship is key for the preservation and flourishing of biodiversity.

Brazil’s first major climate change litigation came before its Supreme Court in September 2020, when the court held a public hearing about a range of challenges concerning climate change and the actions and omissions of the Brazilian government, especially those related to the Climate Fund set up by the Brazilian government in 2009.10 The plaintiffs had not intended the case to be a pivot of environmental justice: their original claim had been to compel the government to reactivate the climate fund towards fulfilling its international obligation.

However, the court’s response was to conduct a major public hearing exercise over two days, hearing testimonies from climate scientists, environmentalists, Indigenous people, representatives from the agribusiness and financial sectors, non-governmental organisations, economists, legislators, and federal representatives and state governments. Interestingly, the court did not consider the limits of its powers, or limits on what matters could be entertained in climate litigation. This openness was a significant leap for the Brazilian judiciary: the nature of the litigation and the approach to environmental jurisprudence were unprecedented. According to presiding Judge Barroso, the public hearing was a ‘plural conversation’, and he also stated that climate issues were not confined to the legal or policy domain. Rather, they were to be treated as an interdisciplinary concern affecting various stakeholders, some more disproportionately than others. While the matter is pending a decision at the time of writing, other challenges of a similar nature soon followed. Two months later, the Partido Socialista Brasileiro and a group of other political parties brought a further challenge against the Federal Government of Brazil on the grounds that its non-implementation of the national deforestation policy had contributed to climate change and violated the fundamental constitutional rights of its citizens. This petition primarily focused on the adverse impacts of deforestation on the rights of Indigenous people; it gave an extensive account of the ways in which deforestation, the expansion of logging industries, and the destruction caused by extractive activities such as gold mining, have destroyed Indigenous cultural knowledge and ways of life. The challenge awaits full judgment.

Never again?

The institutional and ideological networks that sustain colonial and extractive capital are embedded in a maze of corporate structures and state apparatuses that extends around the world. An Anglo-Australian company has bloodied footprints in Bougainville, West Papua, Indonesia, the US, South Africa, Guinea. Canadian mines ravage Latin American nations and the poorer countries of Africa. American corporations plunder and destroy Ecuador and go after people who defend the land. Shell has a long history of wreaking destruction in the Niger Delta and wherever it has set foot. While we cannot always make out the exact contours of all the different varieties of multinational corporate engagement with local communities, or the forms of fairness and participation that provide cover for the smooth functioning of extraction, there is but one logic to their existence – capital accumulation. Resource conflicts result from the violence of capital accumulation and profit generation in the face of demands for a more equal social and economic world. As the cases discussed in this article tell us, Indigenous lives, cosmologies, cultural and spiritual heritage are constantly erased at the behest of capital. And until there is a larger reconciliation project that addresses the foundational premise that enables these erasures, tradeoffs, and disregard for the plurality of living worlds, the assertion of ‘never again’, and the justice discourses within settler colonies, will have little meaning or impact. A sustainable future based on hope and justice will only result from collaborating and working together in the juridical, political and social spheres. Future solutions will be based on active resistance, but also on work towards a constructive reimagination of truly decolonized worlds.

See: Dan Tout, ‘Juukan Gorge Destruction: Extractivism And The Australian Settler-Colonial Imagination’, Arena Quarterly, No 4, December 2020; Jon Altman, ‘The Native Title Act Supports Mineral Extraction And Heritage Destruction’, Arena Online, 16 June 2020.

Benedict Scambary, My Country, Mine Country: Indigenous People, Mining and Development Contestation in Remote Australia, CAEPR Research Monograph, No 33, Canberra, Australian National University 2013.

Inquiry into the destruction of 46,000-yearold caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara region of Western Australia Submission 25 - Supplementary Submission.

Karl Marx, Capital Vol 1, 2013, p. 533.

Clark v Minister for the Environment [2019] FCA 2027.

Talbott v Minister for the Environment [2020] FCA 1042.

Report of the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia, ‘Never Again’, December 2020, p. 33.

See, respectively, ‘How the Saami Indigenous People Fended Off Gatesfunded Geoengineering Experiment’ (15 April 2021): https://www.counterpunch. org/2021/04/05/how-the-saami-indigenous-people-fended-off-gates-fundedgeoengineering-experiment/ (last accessed 15 May 2021); María Paula Rubiano, ‘In Colombia, Indigenous Lands Are Ground Zero for a Wind Energy Boom’, Yale Environment 360: https://e360.yale.edu/features/in-colombia-indigenous-lands-areground-zero-for-a-wind-energy-boom (last accessed 15 May 2021); Chris Hesketh, ‘The Answer Is Blowin’ In The Wind? Clean Energy, Indigenous Struggles And Environmental Justice’, Progress in Political Economy, March 2021: https://www.ppesydney.net/the-answer-is-blowin-in-the-wind-clean-energy-indigenous-strugglesand-environmental-justice/ (last accessed 15 May 2021).

Sakshi, ‘Denying Indigenous Environmental Justice: Experiences from Australia, Brazil, and Canada’, Fourth World Journal, Vol 20 No 2, 2021, pp. 115-130.

Astrid Bernal, ‘ADPF708 / Climate Fund. What to expect from Brazil’s first public hearing on climate policy?’: https://gnhre.org/2020/09/22/adpf708-climate-fund-what-to-expectfrom-brazils-first-public-hearing-on-climate-policy/ (last accessed 15 May 2021). Recordings of the public hearing are available at: https://www.youtube.com/c/STF_ oficial/videos (last accessed 15 May 2021).

Published 27 October 2021

Original in English

First published by Soundings 78/2021

Contributed by Soundings © Sakshi / Soundings / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Why abortion alone does not make women free

Claire Potter in conversation with historian Felicia Kornbluh

Last year’s overturning of Roe v. Wade took abortion laws in the US back to the nineteenth century. But despite the enormity of the setback, the moment provides pro-choice campaigners in the US with an opportunity to widen their political aims.

Despite Lithuania’s Europeanism, its policies on LGBTQ rights are sometimes closer to Russia’s. At the end of 2023, the Lithuanian parliament voted against amending the country’s notorious ‘gay propaganda’ law, in defiance of the European Court of Human Rights.