The quietness of death

In moments of crisis, reflecting on loss can be especially hard. Philosopher Krzysztof Michalski’s meditation on an unexpected death lends gravitas to universal questions of belief, awareness and fear in times of transition.

Turin. The 1920s. A family with no concern of poverty, living the peaceful, imperceptible happiness of the everyday. A boy, twenty-some years old, a student popular with his peers, loved by those around him. A headache, a fever, chills, chest pain – no one pays attention, it’s nothing unusual, his home, full of life, is absorbed by other things. A few days later, the final agony, and death.

Some time passes. His sister, terrified by this death, helpless, full of guilt, returns to those days: How could it be that we knew nothing? How could it be that this boy departed so quietly, so imperceptibly, without being comforted, among a family who loved him, among his friends? All alone?

‘I’m a bit weak’, he had said. Yet there was no one who might have understood him. Even our mother found … only words of excuse for him. It would have been natural for one of us to go to him and put a hand on his burning forehead … But no one did.

Had he himself known what awaited him? Had he seen death approaching, the death others failed to see? Yes – his sister now thinks – he knew, he knew and tried to hide it from those closest to him; for after all, as he had once said, ‘woeful are those who remain behind’. And so his detachment from his surroundings grew greater still.

Only now, looking back, does his sister begin to understand the unconcern, which followed from that distancing, his irritating indifference towards what absorbed us, his family. What weight could all of this have had for him? The bustling about of his mother, father and sister, bereft of any connection to what affected him most – what meaning could this have had? He cared about his family but not about their cares; he was dying in quietness, at a distance from life’s voices. It is precisely in this irritating indifference, this unconcern, this estrangement from his own family, that his sister now sees evidence of a knowledge not given to others – a knowledge of death, hovering nearby.

What kind of knowledge was this? It was not, after all, knowledge of a disease and its consequences. How could the young man have known better than his doctor what awaited him? It was the knowledge of a Christian, thinks his sister. A Christian knows – she recalls her brother’s oft-repeated words – ‘that death can appear at any moment, a Christian’s virtue is an unceasing readiness for death’s arrival’. So he was prepared. ‘If God summons me’, he had once said, ‘I will willingly obey’. Perhaps it was just this readiness that rendered him indifferent towards the concerns of daily life, that enabled him to obey Jesus’s appeal through Saint Matthew: ‘Look at the birds of the air; they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns […] Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin […] Therefore do not worry, saying, ‘What will we eat?’ or ‘What will we drink? or ‘What will we wear?’.1 In the final instance, a Christian knows that the concept of ‘end’ does not exhaust the meaning of ‘death’, that ‘death’ is also a beginning, a chance for birth, for birth – a Christian believes – into a new life. This was why – thinks his sister – her brother, in saying goodbye with the rest of their family to their dying grandmother,

experienced that brief moment entirely differently – as if saying goodbye to someone close to him who was boarding a train, wishing her a pleasant trip, calling out ‘See you later!’, an embrace, a few tears, affection.

Yet can death – even for someone who regards it as a new beginning, even for a Christian – really be compared to a train ride from Warsaw to Łódź? Is it possible to know where the journey leads? Is it possible to know anything at all about the destination? Does a Christian’s readiness for death come from knowledge of what awaits him, like knowledge about the train schedule or about Łódź? Was such knowledge the source of the trustfulness of the young man who was dying alone, in quietness? Was it the source of his calmness towards death?

No, the source of his calmness was not, nor could have been, this kind of knowledge. For what could such knowledge be based on? Be like the lilies, the birds – this is not a plea for a better envisaging of the future. This is, rather, an intimation that life is something more than the object of predictions, plans, calculations and concerns, that life cannot be contained within these things. That perhaps, then, death – the moving away from, the disappearing of all of these concerns and calculations, of the life I have known – is not only an end.

Perhaps a Christian’s readiness for death rests upon just this: not on the knowledge of what will be, not on the certainty of a continuation that relativizes death and in so doing brings consolation, but on the readiness to let go of the concerns and calculations that make up the life he has lived? On the letting go of everything I am, and of everything close and dear to me – in the name of a life I do not and cannot know? (For how can I know what it means ‘to live’ without concern for what I will eat, and drink, without concern for those closest to me? How can I know what life means in the absence of concerns, like the life of a lily, a bird?)

A life without concerns, unknown – Jesus called this eternal life: ‘And everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or fields, for my name’s sake, will […] inherit eternal life’.2 His sister recalls these words; here – she thinks – lay the source of her brother’s indifference towards the affairs of his loved ones, his unconcern towards approaching death. To leave father, mother, children, to give up everything one is, to sever, by a radical incision, the continuity of life as it has existed thus far, to place its meaning, the meaning of the words ‘to live’, under a question mark – is that not beyond a human being’s strength? Complete unconcern, unconcern towards life’s affairs – and so unconcern, too, towards its end, towards death – is that not inhuman? Perhaps this is why her brother’s indifference and unconcern seemed so irritating to his sister? Is not what is human the craving for continuation, for holding life as it is, perhaps reshaping it here and there, but above all the desire that it go on, without end? Is not what is human the fear of an end of everything familiar, the terror that the ‘I’ whom I know – the ‘I’ with all my concerns and pursuits – will disappear, that there will be no me. ‘I know’, says St. Augustine, ‘you want to keep on living. You do not want to die. And you want to pass from this life to another in such a way that you will not rise again, as a dead man, but fully alive and transformed. This is what you desire. This is the deepest human feeling.’3

This essay was posthumously published in 2014 by Gazeta Wyborcza and in the essay collection Eseje o Bogu i śmierci (Essays about God and death, Kurhaus 2014).

Matthew 6:26-31, Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version.

ibid., Matthew 19:29.

Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 344, translated by Peter Brown, in Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (Berkeley and Los Angeles): University of California Press, 1967), 431.

Published 2 May 2020

Original in Polish

Translated by

Marci Shore

First published by Gazeta Wyborcza (14 Feburary 2014) and 'Eseje o Bogu i śmierci' ('Essays about God and death', Kurhaus 2014) (Polish version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by The Institue for Human Sciences © Krzysztof Michalski / Marci Shore / The Institue for Human Sciences / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

One almost wonders what Christianity has added to Roman writers’ reflections on old age, writes Andrei Plesu. The answer: a much greater emphasis on transcendence. But how might the dimension of transcendence contribute to a better understanding and use of old age?

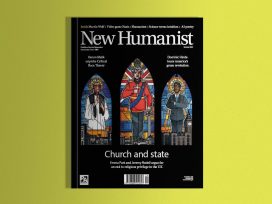

The state of the Church

New Humanist 2/2023

Turing off the tap for the Church of England: why state support for English Anglicanism belongs to the past. Also: Kenan Malik on the flaws of critical race theory.