From carbon absorber to emitter: monoculture, fires, disease and storms are reversing the European forest’s natural role as a Co2 sink. Read about the forests that threaten climate neutrality.

A common currency, a single passport and a European anthem: all were originally the ideas of Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi. But though the founder of the pan-Europa movement was ahead of his time in many ways, impatience with institution-building meant his concrete achievements remained limited.

The 1920s was a troubled time in central Europe. The vast and sprawling Austro-Hungarian empire had imploded in 1918, to be succeeded by a variety of new states, none of them very wealthy or very stable. Optimism was in short supply. Nevertheless, the decade was to see the emergence, within a couple of years, of two powerful young political thinkers born in the old empire who were to make a considerable mark on European politics over the coming decades.

One published at the end of 1923 a short political manifesto, Pan-Europa, which sold out its first print run of 5,000 almost immediately. The other took advantage of a period of enforced leisure in 1924 to work on a book that blended memoir with political ideology and which its author first thought of calling Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice. It was to be published, with a somewhat snappier title, in two volumes in 1925 and 1926.

The author of Pan-Europa was not yet thirty, but this was his third published book. He was ambitious and intelligent, had the benefit of a wealthy background and an elite education and quickly developed connections to influential political figures in more than one country. The author of Four and a Half Years of Struggle had had a turbulent childhood marked by bitter conflict with his father and poor school results. He graduated from technical school (Realschule) aged sixteen, after repeating his final year. It was only after his war service – he was twice decorated for bravery – that he at last discovered, in Munich, the sense of direction that had previously eluded him in his rather aimless bohemian life in Vienna.

He had found the war immensely exhilarating and, like many of his fellow-combatants, felt Germany’s 1918 surrender to be a betrayal. It would not have been easy, in spite of the early commercial success of Mein Kampf (as his book came to be known), to predict which of these two men – the aristocratic, confident and polished networker Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi or the largely unconnected and embittered war hero Adolf Hitler – would make more of a mark on history. Most of their contemporaries in the mid-20s, one suspects, would have guessed wrong.

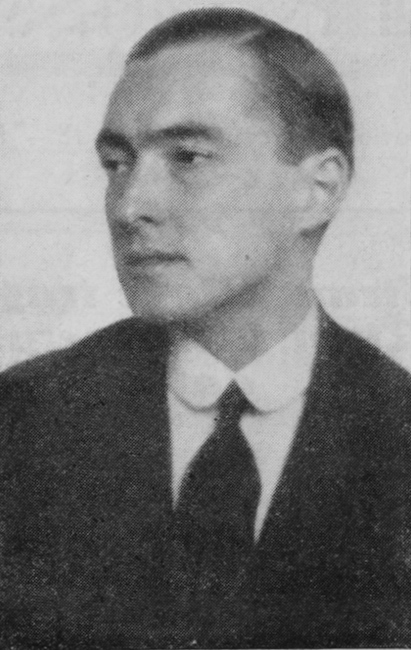

Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi in 1926. Photo by Rozpravy Aventina. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Coudenhove’s Pan-Europa was a study inscribed in the tradition of ‘big picture’ history: a popular genre in the twentieth century, stretching from Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West (1918–1923), through Arnold Toynbee’s multi-volume A Study of History (1934–1961) to Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996).

Echoing Spengler’s approach to the serial rise and fall of civilisations, Coudenhove asserted that it had been the role of Europeans to step into the breach when earlier Asian powers – Chinese, Persian, Ottoman – declined. European influence had been positive: the colonisation of Africa, Britain’s domination of India and the peopling of the ‘empty spaces’ of Canada and Australia were cited. Coudenhove traced European civilisation back to Alexander the Great, who in carving out a Eurasian empire with a pan-Hellenic culture had created ‘the first Europe’. The second Europe was that established by the Romans, chiefly around the Mediterranean, mare nostrum (our sea). The third, which followed the migration of tribes from the north and east (‘barbarians’) into the Roman space, was the Holy Roman Empire, which reached its apogee under Charlemagne.

As that empire began to split into multiple polities the unity that had been lost on the political front was replaced by a spiritual one, when Europe became ‘Christendom’, a process most fully realised during the reign of Pope Innocent III (1198–1216). This was the fourth Europe. Religious unity was shattered by the Reformation, followed in due course by the Enlightenment, the pre-eminent political representative of which was Napoleon, who, for a time, reorganised Europe – the fifth Europe – under French hegemony. Napoleon might have been toppled by the reactionary powers, but the idea of forging a united, rational Europe persisted.

As that empire began to split into multiple polities the unity that had been lost on the political front was replaced by a spiritual one, when Europe became ‘Christendom’, a process most fully realised during the reign of Pope Innocent III (1198–1216). This was the fourth Europe. Religious unity was shattered by the Reformation, followed in due course by the Enlightenment, the pre-eminent political representative of which was Napoleon, who, for a time, reorganised Europe – the fifth Europe – under French hegemony. Napoleon might have been toppled by the reactionary powers, but the idea of forging a united, rational Europe persisted.

The outcome of the fratricidal conflict of 1914–18, however, had seen Europe lose its place in the world. It was now threatened both by the growing financial power of American capitalism and the threat of Bolshevik communism – a destructive, atheistic creed inimical to Europe’s intellectual and spiritual heritage. For Coudenhove, Europe (‘Pan-Europe’ as he called it) had a common culture which rested on two thousand years of history.

As Martyn Bond puts it, ‘Europeans … were carriers of a civilization of global significance, which had achieved great things in all realms of thought and action, and which had the potential to deliver even more in the future. For him, there was self-evidently a European identity, and hence a European nation, and all Europeans could aspire to join it.’ What Coudenhove wished to see established was the opposite of Hitler’s vision – not a community based on common ‘blood’ or ‘race’ (Blutgemeinschaft) but one built on common ideas and values.

At around 150 pages, Pan-Europa was not going to tax the reader too much. Arnold Toynbee was to identify twenty-six significant civilisations in world history but his study of these took him almost thirty years to complete. Coudenhove confined himself to Europe and to six historical stages – one in the future – and managed to knock his book into shape during a three-week stay at the Renaissance castle of his friend Willy Gutmann on either side of Easter 1923.

As with the Marxist version of history, or ‘History’, Coudenhove’s schema had a clear orientation towards the future, an essential element perhaps for any political philosophy which requires its followers to commit to activism. Interpreting the world is fine and dandy, but the point, of course, is to change it. Changing it, or at least changing that part of it in which they lived, now required Europeans to give up their national rivalries and unite in a co-operative structure which would usher in the sixth manifestation of the continent’s long history, a federal United States of Europe.

This construct would exclude both Russia, politically and culturally incompatible, and Britain, which Coudenhove saw as being uninterested in the project, having other fish to fry in its far-flung empire. If Pan-Europa were to have any chance of succeeding, its central, and most difficult, task would be reconciling France and Germany, and this was the field in which he first set himself to labour.

Who was Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi? The double-barrelled surname is intriguing enough, but that is only the start. Hitler, in the third volume of Mein Kampf, referred to him dismissively as ‘that cosmopolitan bastard (Allerweltsbastard)’.

Hitler’s Cosmopolitan Bastard: Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi and His Vision of Europe, by Martyn Bond, McGill-Queen’s University Press

Cosmopolitan is an accurate enough description of his politics, but also indeed of his family background. The Coudenhoves were a Flemish noble family in the service of the Habsburgs who moved to Austria after the French Revolution. The Kalergi or Kalergis family were Cretan Greek, with another branch prominent in Venice. In 1857 in Paris, Count Franz Karl von Coudenhove married Marie Kalergi, the daughter of a famous society hostess and patron of the arts of German and Polish origin who, after separating from her husband, lived in Paris and Warsaw. Marie Kalergi’s son Heinrich, a diplomat in the service of Austria-Hungary, married Mitsuko Aoyama while representing his country in Japan.

One might have thought that Heinrich and Mitsuko’s son Richard, with such a variegated pedigree, would have been at a loss to find further ways of offending the guardians of racial purity. But no: aged eighteen, he met the divorced Jewish stage actress Ida Roland, thirteen years his senior, and quickly fell in love with her. In 1915 they were married, much against his mother’s wishes.

Ida, whose earning power was substantial, was to be a great support to her husband, both financial and moral, throughout their long life together. They were to have no children (Richard adopted Ida’s daughter, Erika) but the Coudenhove-Kalergi ‘line’ still exists, its latest member, born in 2016, Richard’s great-grandniece Olympia Marie Gladys Zita Barbara Mauricette Elena Omnes Sancti Coudenhove-Kalergi – a Christian name for each of her five years and a couple to spare.

Ida Roland-Coudenhove-Kalergi with Thomas Mann at the Pan-Europa meeting in Berlin, 1930. German Federal Archive via Wikimedia Commons

In 1924, Coudenhove received a message of support from the Hamburg banker Max Warburg which offered him funding – equivalent to almost €300,000 in today’s money – to be disbursed over a period of three years and to be spent building a movement, half of it in Germany and half elsewhere in Europe. Coudenhove established a publishing company for Pan-Europa in Vienna, with its own printing presses. From here he published the first volume of the Pan-Europa Journal, an essential pillar of his recruitment strategy for the organisation.

But if he wanted to expand the number of ordinary supporters his focus was just as often on recruiting the influential and powerful as sympathisers or sponsors. The support of successive Austrian chancellors – particularly Ignaz Seipel, Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg – was vital in furnishing him with a solid physical base from which to direct operations. Seipel, a Catholic priest who was chancellor from 1922 to ’24 and again from 1926 to ’29, gave Pan-Europa a suite of rooms in the Hofburg, close to Austria’s seat of government. He also brokered an arrangement with the Cistercian order whereby the Coudenhoves took over a beautiful central Vienna apartment recently vacated by the prior at a very modest rent. Here Richard and Ida’s servants – cook, maid, butler and chauffeur – occupied the ground floor while upstairs the couple entertained and networked with politicians, ambassadors, newspaper editors and distinguished foreign visitors.

By the end of 1925, Pan-Europa had sold more than 40,000 copies. By 1928, translations had appeared in French, Spanish, Hungarian, Czech, Croatian, Greek, Latvian, Japanese and of course English – though the latter was published not in London but New York. Coudenhove hoped to organise national Pan-Europa committees in all the countries of the European mainland but also to find sympathisers in Britain and the US. These would contribute funding to sustain the expenses of headquarters and the ambitious programme of the union, of which Coudenhove had taken the precaution in 1926 of making himself president-for-life.

In France and Germany he sought out non-nationalist, or less nationalist, figures with whom he thought he could do business. Chief among them were the foreign ministers Aristide Briand (France) and Gustav Stresemann (Germany), who were to be jointly awarded the Nobel peace prize in 1926. If Briand’s support for Coudenhove’s federalist aims was enthusiastic (‘Go ahead, quick, quick, quick!’) the same could not quite be said for Stresemann, who knew how much resentment there still was in Germany over the terms of the Versailles treaty and consequently how carefully he would have to tread in any move towards reconciliation with France. Martyn Bond comments:

Stresemann … was cautious, but offered RCK his unofficial support, essentially because Pan-Europa opened an alternative route for Germany to achieve a better understanding with France … But Stresemann wanted to keep his options open to the east as well. He refused to recognize Germany’s new border with Poland, for instance, since, if ever Poland was attacked by Russia, Stresemann knew his country could demand a territorial price for supporting its eastern neighbour. RCK noted succinctly, ‘He was a European as far as he thought that Pan-Europa might serve Germany’s national interest.’

Which is to say perhaps not very far.

As a young man, Coudenhove had entertained some mildly leftish ideas: that is he believed that a more equal redistribution of wealth in society might be advisable in the interests of justice and to stave off social disorder. But he was not particularly enamoured of the idea of political equality as such. He never regarded Bolshevism as anything other than a serious threat – one ‘based on Asiatic principles’ – to civilised western values, and while he cultivated some German social democrats and French socialists during the 1920s and ’30s in the interest of spreading more widely his ideas on Europe, he remained rather ambivalent about the essential political basis for both liberalism and democratic socialism – universal suffrage and the competitive free play of political ideas and organisations. Bond writes:

He had his doubts about social democrats and liberals … since their embrace of democracy failed his test of ‘quality’ by sacrificing power to the lowest common denominator in the state, the highest number of voters … The universal franchise was by definition too democratic, opening the door to rule by the masses or rule by money, by an ignorant mob or the pretention of plutocrats who knew the price of everything and the value of nothing.

The alternative to rule by the masses or by ‘plutocrats’ was of course rule by aristocrats, the governing principle of the world into which Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi had been born, as son of the lord of Ronsperg, Stockau and Muttersdorf (today in the Czech Republic), in 1894. Aristocratic titles were abolished by the new, postwar Republic of Austria, though Coudenhove continued to use the ‘courtesy title’ of Count.

But if the old aristocracy had had its teeth drawn in many countries in the early years of the twentieth century, might there possibly be a new one in the making? Bond tells us of a visit Coudenhove made to Rome in 1933 to see Mussolini. The two men found they had a good deal in common. They were both keen on Nietzsche. Mussolini scoffed at the notion of German or Aryan racial superiority: it was the barbarians of the north who had throughout history threatened the more civilised nations of the Mediterranean south. Antisemitism was an absurdity. Coudenhove thought he could even a detect a warmth towards the ideas of Pan-Europa. As Bond puts it, ‘the man changed before his eyes from dictator to intellectual’.

Hitler, as a racist and antisemite, was beyond the pale, but fascism in its Italian form seemed to Coudenhove to have some positive qualities, mitigating the weaknesses of democracy by organising the business of government around a strong leader constantly in contact with professional and other elites, ‘all welded together into a national movement that did away with conflicting political parties and divisive popular choice’. When Italy invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935 Coudenhove refused to condemn the operation, on the grounds that condemnation would only push Mussolini into Hitler’s arms.

Besides, in Pan-Europa, had not the African continent been designated as the happy hunting ground of the European powers, a permanent source for food and raw materials? In a conflict that stretched over several years, joining up with the Second World War, the Ethiopians estimated their dead at 700,000, very many of them civilians and about a third killed by chemical weapons.

The German-Italian agreement of 1936 might have forced Coudenhove to admit that his assessment of Mussolini had been mistaken, but he kept hoping until the last minute that alliances might be reversed and Italy might in the end join France and Britain in resisting Hitler. He was soon to have greater worries, however, than chagrin over a political misjudgment.

In 1938, Hitler demanded that the Austrian chancellor, Schuschnigg, withdraw his proposed referendum on unity with Germany (Anschluss). Schuschnigg resigned and was replaced by the Nazi sympathiser Arthur Seyss-Inquart, who invited German troops into the country. Coudenhove, who would certainly have been on ‘the list’, quickly fled with his wife across the Czech border and on by a roundabout route, through Hungary, Yugoslavia and Italy, to their country house in Gruben, Switzerland.

After the fall of Czechoslovakia, Coudenhove, who had been travelling for some years on a Czech diplomatic passport, applied for and was granted French citizenship. He had spent much time in these months of ‘phony war’ visiting Paris and London, but in May 1940 he and Idel left Gruben and drove across France, crossing the Spanish border at Port Bou, with the ultimate aim of reaching Lisbon in neutral Portugal. After six nervous weeks there he eventually cleared the considerable hurdles erected by US bureaucracy and flew to New York.

Coudenhove’s years in New York can possibly be considered secondary to a study of his influence on the movement towards European unity. Suffice it to say that he found a job teaching at New York University and continued to write and network, though he mostly failed in his efforts to make an impression on the Roosevelt administration, for whom his unambiguous anti-Sovietism was at this time inopportune. Nor was he welcome at the British embassy in Washington. A note on internal foreign office correspondence dated 1943 described him as ‘more a nuisance than a danger’, since he had ‘no backing’.

The Washington ambassador, Lord Halifax, previously Neville Chamberlain’s foreign secretary, also believed that Coudenhove was ‘in touch with a number of disreputable people’ and asserted that he ‘wouldn’t trust him at all’. Halifax, who had gone fox-hunting with Hermann Göring in the 1930s and was at pains to assure Stanley Baldwin that ‘these fellows [the Nazis] are genuine haters of Communism, etc.’, can be assumed to have known all about the disreputable. One might speculate that Halifax’s reluctance to trust Coudenhove stemmed from his very obvious ‘cosmopolitanism’. While some who met him might have been impressed, others, of the plain man variety, obviously were not. As Bond puts it:

He was hard to place. What country or what party did he belong to? Half-Japanese, but originally from Austria, and since September 1939 a French citizen, he had in earlier years been travelling on a Czech diplomatic passport and had a home in Switzerland. Where did he belong? … To whom did he owe allegiance? If asked, he would have answered ‘Europe’, but in the eyes of the Allied governments, he had no locus other than that of an independent author from Central Europe, temporarily employed as a lecturer in New York University. He was a citizen of nowhere.

Martyn Bond’s nationality and his career background – foreign correspondent for the BBC, university professor, European civil servant – have perhaps influenced him to trace in particular detail Coudenhove’s ideas in so far as they affected Britain, and indeed to offer a more general short history of that country’s engagement with Europeanism in the twentieth century and in particular in the postwar period.

One of the earliest references is to Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald, who offered the view that the idea of a united Europe was premature, though one might consider it in ten years’ time – that would be 1939. In the postwar period Coudenhove thought for a time that with Germany out of the equation – it did not become a sovereign state again until 1949 – Britain might step into the breach, discovering a new European vocation. He forged a very amicable relationship with Winston Churchill, though it gradually became clear to him that Churchill’s inspiring rhetoric on European history, culture and destiny did not necessarily imply support for any concrete proposals, still less ones that might tear Britain away from its more important links with ‘the English-speaking peoples’.

Churchill’s son-in-law Duncan Sandys became a particular bugbear for Coudenhove, as indeed he did for another European federalist, the Swiss Denis de Rougemont. Sandys, Bond writes,

represented a particularly British view of the issue of European integration. He shared with Churchill a vision of Europe as a group of nation states with a common cultural heritage which would all benefit by co-operating voluntarily with each other on economic and other issues. But Sandys saw no need for a closer political bond between them, certainly not one which would lead to the creation of a common European citizenship and a federal structure of government, since this would inevitably be exclusive and run counter to the interests of Britain and its Commonwealth …

What Britain wanted was an alignment of aspirations, a meeting of minds, a warm, fuzzy Eurocultural feeling that would involve few or no actual commitments but possibly a lot more conferences, dinners and inspiring resolutions. In the longer term some of those who at the time suppressed their doubts about British intentions for the sake of ‘unity’ in the movement came to regret their weakness. The French socialist minister André Philip, looking back in the late 1960s, observed: ‘To the degree to which we buried the genuine problems we allowed ourselves to be sidelined by the establishment. In our fight for Europe we did not spill any blood, which is excellent and I am grateful for it, but we spilled too much champagne.’

When, in 1961, Britain finally applied for EEC membership under prime minister Harold Macmillan, Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell was scathing about Tory ‘double talk’ on Europe. There might indeed be pragmatic reasons for going in if the terms were right, Gaitskell suggested, but the ideal terms for him seemed to be those which entailed as little Europe as possible:

When they [the Tories] go to Brussels they show the greatest enthusiasm for political union. When they speak in the House of Commons they are most anxious to aver that there is no commitment whatever to any political union. We must be clear about this. It does mean, if this [political union] is the idea, the end of Britain as an independent European state. I make no apology for repeating it. It means the end of a thousand years of history.

While the Benelux states were keen that Britain should join the community and act as a balance to the developing French-German axis, President Charles de Gaulle saw the British as a threat to French leadership and a possible Trojan horse for American interests. In 1963 and again in 1967 he used his veto to block their applications. When, in 1972, de Gaulle having been succeeded by the more friendly Georges Pompidou, Britain finally entered the European Communities, there were some who remained sceptical of the merits of joining a club which had so recently baulked at accepting them as members. Left-wing Labour minister Peter Shore reminded his parliamentary colleagues that

we are dealing with a government in France, or perhaps I should say ‘a regime’, that is not – I use a rather British understatement – all that friendly to this country, and that whatever the right description of our relationship with France is, we should be unwise to expect consideration, foolish to expect generosity, and ludicrous if we thought of it as having anything to do with community.

Coudenhove had cultivated prominent statesmen over many decades, often with considerable success, forging useful links with the foreign ministers Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann, with three Austrian chancellors, with Harry Truman, Winston Churchill and Konrad Adenauer. His closest political friend, however, was Charles de Gaulle, with whom he developed a relationship that was not just mutually respectful – even warm – but profitable: de Gaulle arranged in the early 1960s for Coudenhove to receive a regular allowance from French state funds, an annual sum equivalent, Bond suggests, to the pension of an ambassador.

Coudenhove had always been drawn to ‘great men’, and there can have been few who projected the mystique of greatness in a more concentrated way than de Gaulle. One could argue, however, that his desire to be close to power and to exercise influence may on this occasion have involved some cost to his political principles. In summer 1950 he had written an angry letter to Bill Donovan, former head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA, accusing him of colluding in switching US support from his own federalist European Parliamentary Union to the European Movement:

Under the influence of Duncan Sandys and Josef Retinger … you have broken off your original cordial relations to the EPU and become the American Agency of the European Movement, providing it with funds and publicity in the USA. As you knew, the European Movement has from the very start been most hostile to the EPU because the latter is promoting a genuine United States of Europe, while the EM has been set up under British leadership with the very purpose of preventing such a European Federation by organising Europe as an association of sovereign states.

The Treaty of Paris of 1951, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), aimed to attain a political goal largely through economic means. The treaty was based on the ‘community method’ of co-operation elaborated by the public servant Jean Monnet. Its preamble stated: ‘Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity.’ Monnet’s preferred version of relations between states involved a pooling of (some) sovereignty and the creation of supranational institutions like the European Commission, which was legally required to act in the common interest; this meant not overriding the interests of small states.

De Gaulle, on the other hand, tended to see Europe in loftier terms, not principally of economic and social policy but of high politics, foreign policy, security and world standing. He was opposed to Monnet’s supranational vision, preferring a Europe des patries (Europe of the nations), in which, however, some patries would be more equal than others. The lead in policy matters in Europe would have to be taken by a group of the largest and most populous nations, a directoire.

In theory, de Gaulle was prepared to admit Britain into this directoire if it eventually fulfilled the conditions to join Europe, but any minnows it might bring in with it (like Denmark or Ireland) would be staying outside with Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. A Europe of the nations was not quite what Coudenhove had signed up for in 1923 with Pan-Europa; one can perhaps at least partially attribute his apparent rapprochement with the Gaullian vision to his admiration for ‘men of action’ and his lack of aptitude for patient institutional work leading to positive incremental change.

Portrait of Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi by Thomas Kosma, in Klosterneuburg, near Vienna. Photo by Patek, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

How can we sum up Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi? Some of his contemporaries were critical. The Berlin nationalist publication Politische Wochenschrift saw him as ‘Narcissus leaning over the pool and observing his reflection’, motionless and unaware of ‘the most urgent intrusions of political reality’. Few (Lord Halifax apart) seemed to doubt his sincerity or moral rectitude, though some thought he might perhaps keep too good company.

The pacifist journalist Carl von Ossietzky thought Pan-Europa was in danger of becoming a ‘movement of intellectuals without any popular base’, due to its founder’s predilection for unselectively gathering powerful figures around him and ‘getting nothing in return but a few kindly granted handshakes’. He might be a good European but he had the ‘sweet, childlike belief of an Austrian’ in the power of connections. He had ruined the essentially good idea of Pan-Europa by ignoring the masses and ‘circulating only in grand hotels and exclusive concert halls’.

Enrolling ‘the masses’ in a pan-European movement might not have been easy as Ossietzky seemed to think but it is probably fair to say that Coudenhove never tried, in fact never even thought of trying. His inclination to live ‘the good life’ – staying in the best hotels, travelling in a chauffeur-driven car, keeping a small retinue of servants – seems to have stemmed as much from his notion of the dignity of his mission as from any personal addiction to luxury.

He was not a bon viveur – neither gourmet nor drinker – but he believed he was the ambassador for Europe and he lived all his life in the style appropriate to the ambassador of an important state. He was not pursuing personal enrichment, but he can be convicted of a certain loftiness or detachment, or more simply callousness, born perhaps of the considerable distance he kept between himself and the experiences of the working class and peasantry. The ten million who had died in the First World War, he said, were replaceable, but not the ten among them who might have been geniuses.

On the positive side he was certainly not as hopelessly utopian nor as politically isolated as some of his critics suggested. Why would someone entirely without influence have attracted the hostility he did (not least from the British foreign office)? He was consistent in his opposition to Nazism and in his commitment to a Europe at peace. He was an innovative thinker ahead of most of his contemporaries: a European flag, a common currency, a single passport and a European anthem (the “Ode to Joy”) were all originally his ideas. In terms of concrete achievements, however, he had the misfortune to be overtaken by a very well-equipped train running on a parallel track.

He was above all a man distinguished by sharp focus and strong determination and a skilled and patient organiser at a time when building networks across international borders was a lot more difficult than it is today. In all of this he was sustained by unshakeable belief in the importance, and in the ultimate success, of his project. He received countless awards and in the 1930s was nominated year after year for the Nobel peace prize. But he never won it. His comment on this is typical of the man and certainly suggests no small degree of self-regard: ‘Better to have deserved it but never been awarded it than to have been awarded it but not deserved it.’

Martyn Bond’s biographical study is a thoroughly informed, fluent, judicious and wide-ranging work, covering not just the career of Coudenhove-Kalergi but also offering a clear and accessible account of the wider political situation in the mid-twentieth century and in particular during the early decades of European construction.

In a note on the title prefacing his text Bond writes: ‘After the destruction of the Second World War, when Europeans were starting to get their act together again, it was to Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s ideas that they turned. Today, we are a long way down the road to turning his utopia into a reality.’ This is certainly an unusual remark to hear an Englishman make in 2021; let us look on it as the informed judgment of a proud European.

Published 17 January 2022

Original in English

First published by Dublin Review of Books

Contributed by Dublin Review of Books © Enda O'Doherty / Dublin Review of Books

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

From carbon absorber to emitter: monoculture, fires, disease and storms are reversing the European forest’s natural role as a Co2 sink. Read about the forests that threaten climate neutrality.

Although incoming migrants are demonized in political discourse, many European countries are struggling with a loss of population. In this episode of Standard Time, Eurozine’s colleagues talk about the idea of ethnic purity, outmigration, and finding a sense of belonging.