The limits of protection, prevention and care

A miniseries on refugees in the COVID-19 pandemic

The European response to coronavirus so far has been focused on nation states and citizens, leaving stateless refugees without means of prevention. Overcrowded and underserved camps have posed a health hazard already before the virus. Eurozine launches a miniseries to report on refugees’ situation on the EU’s frontiers.

The COVID 19 Pandemic has rapidly come to dominate politics and society in many parts of the world. In the EU, the introduction of national border controls, travel bans and national lockdowns have suspended public life on a scale unprecedented in recent memory. The lasting effects of this disruption have already become key topics in the debates on our present and futures.

This article is the first part of our miniseries on refugees’ and asylum seekers’ situation in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read Chiara Pagano’s report from Italy, Artemis Fyssa and Bilgin Ayata’s report from Greece, and Kenny Cuper’s account on the restrictions of the freedom of movement.

With this miniseries on the place of refugees in the responses to the COVID–19 Pandemic, we seek to explore relations between states and subjects by putting refugees in the centre of analysis. Our focus is the situation of refugees in Europe, but the analysis can be extended to the Mexican-US border, refugees in Bangladesh, internally displaced persons in Syria or Palestinians in the occupied territories.

In the present world order of nation states, refugees remain the disruptive mirror image of the right-bearing citizen, despite the emergence of an international protection regime for refugees in the past 70 years. In the past weeks, we have seen the resurgence of the restrictive nation state, the suspension of asylum procedures in several EU member-states, and the absence of concrete protection measures for encamped refugees.

Even in the European Union, the responses to this global threat have been mostly national, putting the nation-state and citizen forcefully into the centre of action. The early calls for help by the Italian government were widely ignored by other EU member-states. Powerful countries like Germany and France were busy with their own preventive measures to contain the virus or repatriating their citizens from their holiday destinations in expensive airlifts. The EU is standing on the sidelines of national races to ‘flatten the curve.’

It’s national economies, national public health, national education systems that European leaders talk about. Yet, in contrast to the divisive nationalism of aspiring fascists like Trump and Orbán, the rhetoric of the crisis nationalism by Merkel and Macron have been emphasizing care, consideration and solidarity. We need to stay at home because we need to protect the vulnerable, they are calling upon their population.

Without doubting the importance of this call, the critical question is, who constitutes the vulnerable in a state of emergency that declares the nation at risk? Or, to put it differently, who is silently excluded from protection and erased from the polity of vulnerable?

As a vulnerable population, refugees are at heightened risk during encampment anywhere in the world during a public health emergency. Yet in the EU, there is an intersecting of two crisis policies that creates additional factors.

The narrative of a ‘European refugee crisis’ was evoked in 2015 when nearly 2 million asylum seekers entered the EU via Greece and Italy within a year. Even though the number of total arrivals to the EU was rather small in proportion to those hosted by Turkey, Jordan or Lebanon, the crisis discourse was repeatedly employed by the increasing polarization among different member-states. A set of new measures was soon put into practice by the European Commission that paved the way for further militarization of migration control at the southern frontiers of the EU.

The European Agenda for Migration presented by the Commission in 2015 introduced the Hotspot Approach which allows EU Agencies such as FRONTEX and EASO to operate and intervene in the national migration management of EU member states. So far, this approach has been imposed on Italy and Greece to ensure fingerprinting, identification and registration in so-called hotspot facilities.

Seemingly administrative in nature, these procedures actually present a biopolitical filtering mechanism based on one’s nationality that determines who will be allowed to lodge an asylum application and who will be pushed back as an underserving migrant. This preselection is based not on individual but collective criteria, thus violating the 1951 Geneva Convention and the EU’s commitment to it. Moreover, presented as a temporary emergency measure, no overarching legal framework has been presented for the Hotspot Approach, even though it has already shaped the fate of thousands of asylum seekers.

What we can see here is how the EU’s efforts to prevent unauthorized arrivals at its frontiers are moving to a grey zone outside of law, enabling systematic human rights violations as well as the neglect of its obligations to protect refugees. All of these developments are built on earlier policy measures, yet were intensified and consolidated in the discourse of the refugee crisis.

It may have already faded that just before the pandemic lead to severe crisis measures, the European public was still actually concerned with this issue. When Turkey opened the borders for refugees towards Greece on 1 March, the perceived threat of a second ‘refugee crisis’ unfolding at the Greek-Turkish border was seen as a greater concern than the further spread of COVID–19.

Fearing that another large arrival of refugees would revive the crisis scenarios of 2015, the militaristic response by the Greek government was met with overall support by the EU. The President of the EU Commission Ursula von der Leyen visited Greece and thanked the government for being a shield of Europe, protecting the external borders of the EU from migration.

Only a few days later, one by one, EU member states began to react to the spread of the coronavirus by reintroducing national border controls and imposing travel bans. In a dramatic shift of events, states took recourse to extraordinary emergency measures; ironically measures that were so far reserved for refugees and asylum seekers in camps: restriction of movement, rationing of supplies, triage, containment, spatial isolation.

In the course of a few days, suddenly European citizens received a mild taste of what it means to fear for freedom, medical care, education, safety, food, and yes, soap and toilet paper. The measures to contain the spread of the virus have put on hold some of the basic rights of citizens themselves.

The existential question for thousands of humans trapped in camps across Europe is, what this shift now entails for refugees. When the limits of democratic standards have already been stretched so far even for citizens, what awaits the stateless? Who is going to protect the rightless and most vulnerable in the state of emergency?

This miniseries explores these questions for two pressing reasons. For one, we concur with many political theorists that the treatment of those deemed by society and politics to be other, foreign, rightless and marginalized must be at the heart of reflections on the contemporary condition as a harbinger for the future. Furthermore, as scholars working on migration and encampment, we are driven by a deep concern for what is already unfolding in front of our eyes, without veritable action taken for refugees in overcrowded camps, be it in Greece, Italy, or elsewhere.

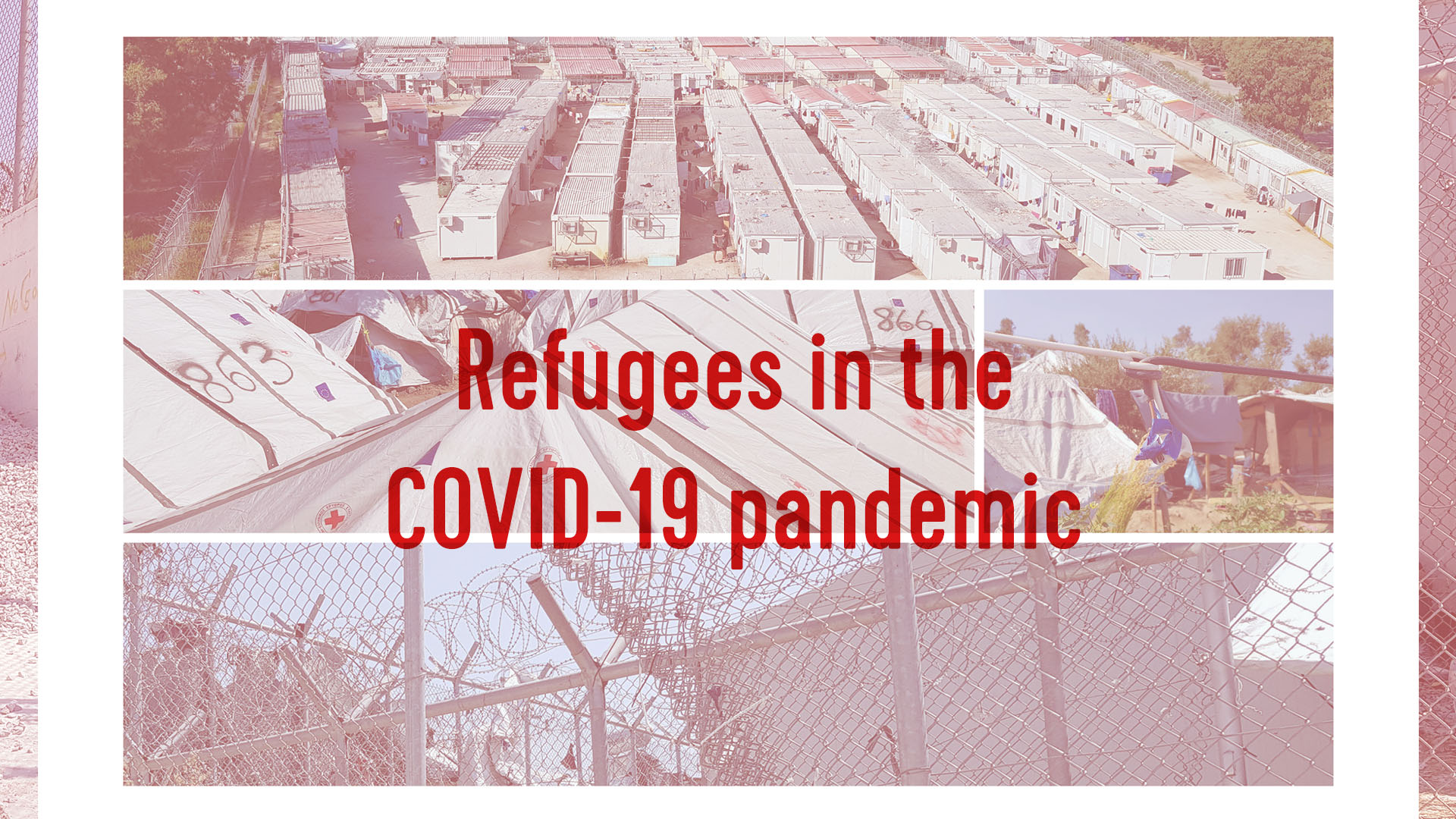

As part of our comparative research on the role of infrastructure in migration management1, we have visited the hotspot facilities in Greece and Italy in the summer of 2019. To put the obvious first: as numerous NGOs, scholars, and journalists have already pointed out, the Greek hotspots are bereft of conditions for a dignified human survival. Our own field research only corroborates the devasting accounts of the lack of basic infrastructure, a systematic and chronic condition for the past four years.

Like everyone who ever visited these camps, we left ashamed, angry and in disbelief. The encampment of refugees in barbed wired facilities, many of them escaping war, poverty, and destruction to which European countries contributed or are beneficiaries of, invoked historical images that weren’t easy to process.

While the camps in Lesvos and Samos resemble informal settlements that extend way beyond the actual camps due to their massive overcrowding, the hotspot facilities in Chios, Leros and Kos are more contained, yet do not offer better conditions. Insufficient access to water, food, shelter, medical care, sanitation is the normalized reality in these camps, as well as in Italian hotspot and first reception centres, where physical protection, safety, or privacy is scarce.

Already before the pandemic, the UNHCR and doctors have warned that these camps could become a hotbed for diseases and should be closed. The threat of the coronavirus only aggravates the health hazards these camps themselves pose. The most basic preventive recommendations from COVID-19, such as social distancing and washing hands, are impossible to be followed in these camps.

In the last few days, the calls of NGOs and politicians to evacuate these camps have amplified and were followed up in the European Parliament. Social media campaigns such as the online protest on March 29th of the initiative #LeaveNoOnebehind are gathering growing support. In remarkable contrast to the countries which suspended their asylum procedures, Portugal has announced on 28 March that it will treat all non-citizens like permanent residents to ensure everyone’s access to life-saving public services.

These actions and movements for solidarity and equal treatment are important interventions to challenge the citizen-refugee divide and the limits of protection. The EU Commission itself has so far been unresponsive to these calls, failing to address the issue and to take action. It must be clear that this decision of deliberate neglect of refugees in the pandemic not only foils the very meaning of vulnerability, but also entails their willful sacrifice.

This article is the first part of our miniseries on refugees’ and asylum seekers’ situation in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read Chiara Pagano’s report from Italy, Artemis Fyssa and Bilgin Ayata’s report from Greece here, and Kenny Cuper’s account on the restrictions of the freedom of movement.

The miniseries is a co-production with the research project ‘Infrastructure Space and the Future of Migration Management: The Case of the EU Hotspots in the Mediterranean Borderscape.’

From national threat to oblivion

Erasing migrants from public discourse in Italy during COVID-19

Politics of abandonment

Refugees on Greek islands during the coronavirus crisis

Contagion and containment

Curtailing the freedom of movement in times of coronavirus

The research project examines the implementation of the Hotspot Approach in Greece and Italy and explores its effects on Tunisia, Libya and Turkey. The interdisciplinary research team consists of social scientists and architects. The project is funded by the Swiss Network for International Studies.

Published 31 March 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Bilgin Ayata / Research Project ‘Infrastructure Space and the Future of Migration Management: The Case of the EU Hotspots in the Mediterranean Borderscape’ / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

After the catastrophic performance of the traffic light coalition, what Germany needs is a strong, unified government able to provide an antidote to the new fascism. Friedrich Merz must begin by rebuilding trust, writes the editor of ‘Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik’.

Pro-Irishness was part of the Democratic-Party-dominated political culture that MAGA despises and whose day is done. Time for Ireland to opt once and for all for Brussels over Boston, argues the co-editor of the Dublin Review of Books.