In New Literary Observer, Oleg Voskoboynikov considers one of the most widely studied sacred images in western art: the Lateran icon of the Saviour in the Sancta Sanctorum (the Pope’s private chapel) in Rome. In a combined study of Nicola Maniacutia’s Treatise on the Lateran Palace Icon, written in the 1140s, and the Lateran icon, Voskoboynikov illustrates the important, premodern concept of the ‘living icon’. The Lateran Christ is one of the foremost examples in the West of a miracle-working icon ‘not made by human hands’ (the scholarly term is an ‘acheiropoieton’).

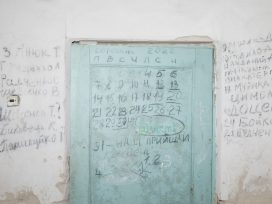

Between the eighth and the sixteenth centuries, the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin (15 August) was celebrated in Rome by a procession carrying the icon of Christ from the Lateran Palace to Santa Maria Maggiore. There, the image ‘met’ the holy icon of the Virgin, known as the Saviour of the Roman people (Salus populi romani). The enormous importance of the event lay in the belief that the images were ‘living’ – that Christ and the Virgin were actually present in their icons.

Sacred ‘place of memory’

The Russian equivalent of the Lateran Christ in the West is the Vladimir Mother of God, the famous twelfth-century Byzantine icon, brought to Russia in the medieval period. Peter S. Stefanovich considers the reception of the icon in the 1500s and 1600s, drawing attention to the famous painting The Panegyric to Our Lady of Vladimir (1668) by Simon Ushakov, also known as The Tree of the Russian State.

In Ushakov’s work, portraits of saints connected to Moscow, Russian tsars and patriarchs are depicted in medallions, growing as fruits on a tree. As a symbol of the Russian state, the tree is being watered by Prince Ivan Kalita and the Metropolitan Petr, while Jesus is watching from above. This is ‘a sacred-dynastic construction’ that appeals not only to ‘faith but also to dynastic memory’.

The idea of Russia’s heavenly dynasty and Moscow as both sacred ‘place of memory’ (Pierre Nora) and political centre also comes across in texts from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-seventeenth centuries, in which we are told that the Vladimir Mother of God miraculously saved the city from the Tatars in 1521.

Fused images

Andrey Vinogradov looks at images that combine the established genre of donor portraiture – for example the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian at Ravenna – and representations of the Virgin with outstretched arms, interceding with God on behalf of humanity. A rare example of the fusion of these two types of images is the mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI kneeling (proskynesis) before Christ, above him a medallion with the Virgin as intercessor.

This article is part of the 6/2021 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing.