Talk of demilitarization and mobilization divides opinion. Could giving women and other feminized groups more agency in wartime decision-making flip their traditionally passive role, providing relief from trauma and injustice?

Spilne author Evheny Osievsky became a soldier in the Russo-Ukrainian war. Gwara Media editor-in-chief Olena Myhashko pays her respects to a colleague who put his research aside to go into battle, highlighting the weight of personal bereavement and Ukraine’s ongoing loss.

One year on and I was one of the lucky ones who still hadn’t had casualties among her friends. That changed on 27 May when I discovered that Evheny Osievsky, a Ukrainian PhD scholar, had died near Bakhmut.

I was working as a lifestyle magazine editor when Zhenya first offered me his texts, which were too good to be published in a glossy magazine. We got along; he was amazed that I could grasp his bold, playful and niche ideas about Sundance festival documentaries, Jacques Audiard, Sofia Coppola, David Bowie’s music, overlooked references in US comics and marginalized religious communities in Kyiv. It was his balance between irony and poetry, sardonic punchlines and sophistication with a pinch of vagabond charisma that made our conversations warmer and livelier than those I had with other authors back then.

When he voluntarily joined a military unit, he wrote on Facebook:

I have no doubts that when people say ‘those like you shouldn’t fight in wars’, they see it as a compliment, even an expression of support. But I don’t need such support. It’s as if mentioning writing or using the word ‘discourse’ (or whatever guys ‘like me’ do) somehow implicitly make your occupation a more elitist pursuit than of those who ‘just’ defend their families and cities, ‘just’ lose their arms, ‘just’ turn into chopped up meat under a caterpillar tank. But people cannot be split into types and categories. Instead, people here, on the frontline, split their loaf of bread into two, share their tissues, guns, water, gloves, socks, power for phones and body warmth. I call them brothers.

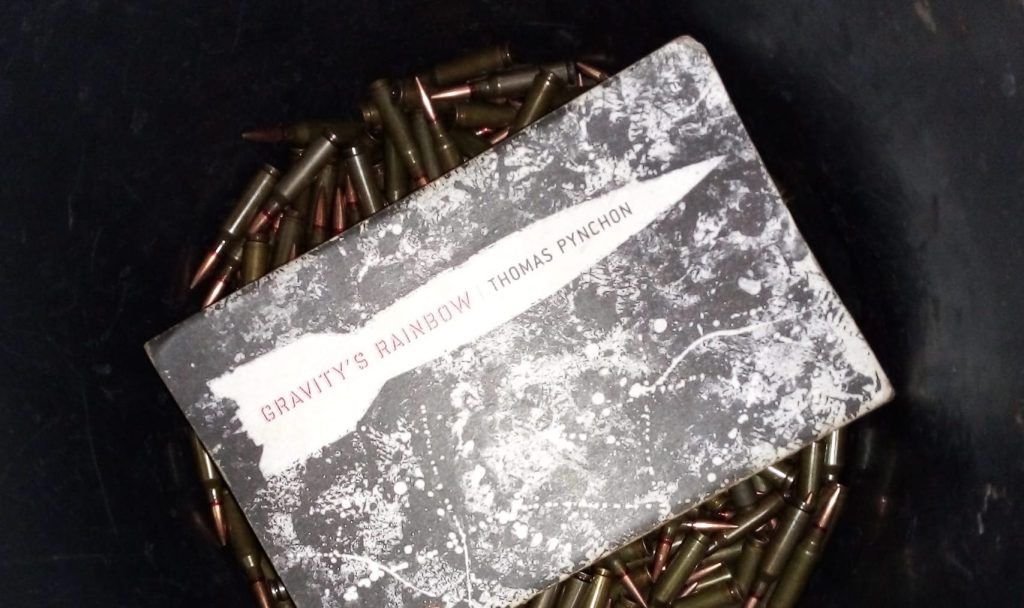

Among the many posts from my information bubble that include terms such as ‘information frontline’, ‘cultural frontline’ or even ‘creative frontline’ (considered rather offensive to those on the actual frontline), Zhenya’s post truly stood out. And yet, his wartime days didn’t prevent him from thinking about his most favorite things and being who he was. He shared photos of reading a Thomas Pynchon novel somewhere in the mud, taking pleasure in the author’s bold and immaculate descriptions.

Photo of Thomas Pynchon’s ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’ in bucket of bullets. Image by Evheny Osievsky

One day in February, Zhenya wrote to me: ‘Hi, it’s been three months since I’ve been in the trenches. Yesterday I snapped and went to the cinema. Managed to watch a new blockbuster. I’ve heard you are in charge of a magazine and I wonder if you can publish my movie review. A film critic joined the army, kept a movie-free diet for three months, but then lost it and – there you go – came up with a review – that’s the text’s concept.’

I refused, saying that the journal had changed dramatically and we only do war coverage now. ‘We’ll have to catch up and get drunk after the victory’, he replied.

It turned out to be his very last message to me; initially, I brushed off the hazy idea of his probable death, as he was still present – alive, spirited and playful.

Zhenya’s death has been the most deafening blast amongst all the drones and missiles I’ve heard so far. And definitely the closest one. Probably not so much because of our periodic friendship but because of the very last conversation we had. I owe you that last piece I rejected, Zhenya; let it be this one.

Evheny Osievsky (1993-2023)

From my subjective wartime perspective, his death also exemplifies why I think Russian intellectuals should give up their media space for more Ukrainian voices to be presented, highlighted, discovered and published. While Ukraine is said to have a bright and highly anticipated democratic future, the final death toll, particularly among soldiers, remains disastrously uncertain. Ukraine’s young, prominent cultural figures being lost again in an enforced brain drain, against the backdrop of the country’s cultural heyday, is a major problem.

Zhenya could have continued writing papers, researching Jacques Audiard and anthropology, frequenting residencies abroad and pondering Pynchon’s works in a safe environment. That would have been regarded as a contribution too. But he chose to put his efforts where his mouth was and illustrate how society defends democracy.

Whether you’re a farmer, doctor or scholar, law violations don’t allow you to sit back. Responsibility doesn’t end after the final full stop in your essays. There’s no excuse, according to Zhenya, not to fight the war you regard as yours. The gap between the so-called multitude and those who read or produce poetry can be easily broken down by basic shared values.

The cost of war is unfathomable, as is the silence that follows such deaths. But that’s the way unity is being built – through poetry, sharing with others and actions that nobody stands apart from.

Links to examples of Evheny Osievsky’s writing:

‘The fallout of dreams, the demonstration of shadows: Watchmen and the atomic zeitgeist of the 80s’, The Comics Journal, 18 May 2022

‘Military insubordination has saved the world from nuclear war several times’, Spilne, 6 July 2022

‘Six cats, thirty people, four mortar shells: Two weeks in the occupied Kyiv suburb’, Spilne, 21 March 2022

Published 31 May 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Gwara Media © Olena Myhashko / Gwara Media / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Talk of demilitarization and mobilization divides opinion. Could giving women and other feminized groups more agency in wartime decision-making flip their traditionally passive role, providing relief from trauma and injustice?

For those who suffered the consequences of Yalta’s division of Europe, the Helsinki Final Act brought grounds for optimism. Today, as Russia’s regressive war on Ukraine reopens old conflicts, it stands as a monument to European modernity.