The forgotten roots of World War I

Those who wish to pass off World War I as a just war against German militarism should remember that at the heart of the global imperialist network stood not Germany but Britain, writes Kenan Malik. And that behind imperialist expansion lay venomous racism.

The nations of the world, claimed Lord Salisbury in a speech to the Primrose League at the Albert Hall in 1898, were divided into the “living” and the “dying”. The “living” were the “white” nations – the European powers, America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The “dying” comprised the rest of the world. “The living nations”, Salisbury claimed, “will gradually encroach on the territory of the dying” and from this “the seeds and causes of conflict among civilized nations will speedily appear”. The partition of the globe “may introduce causes of fatal difference between the great nations whose mighty armies stand opposed threatening each other”.

Less than twenty years after Salisbury gave his speech, the mighty armies of the great nations did indeed stand opposed threatening each other, and bringing calamity upon a generation. Virtually from the moment that the “lamps went out all over Europe”, in Sir Edward Grey’s evocative phrase, there has been much debate – too much debate – about why they did so and who snuffed them out, not least in this, the centenary year of World War I.

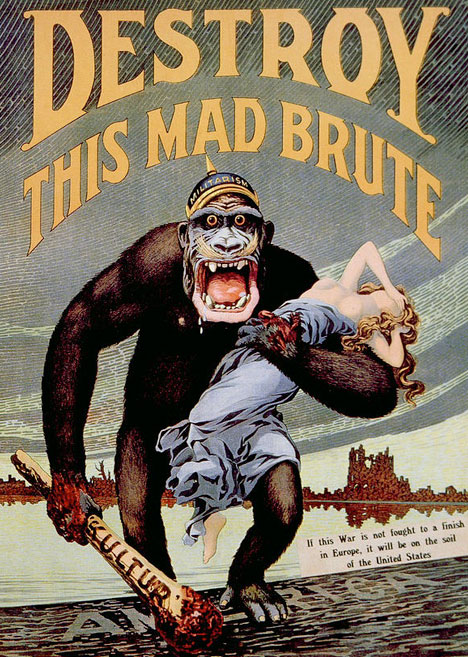

A US army recruitment poster from WWI

Yet in the midst of the often fractious claim and counter-claim, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the issue raised by Salisbury – how the encroachment of the “living nations” upon “the territory of the dying” created “the seeds and causes of conflict”. There has been, particularly this year, much discussion about the role of German militarism. Many who want to make a case for World War I as a good, or at least as a necessary, conflict, have argued for the importance of Britain having stood up to German aggression. Germany’s expansionist tendencies and virulent racism only make sense, however, against the background of late nineteenth-century imperialism, of the carving up of the globe between the Great Powers, as the “living nations” encroached unremittingly upon “the territory of the dying”. Imperialist expansion and Great Power rivalry were, as Salisbury understood, intimately linked. Rivalries helped promote imperialist expansion, while imperialist expansion helped foster rivalries.

At the heart of the global imperialist network stood not Germany but Britain. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain had become the dominant world power, already with an unmatched empire, a powerhouse of an economy, unparalleled naval power and unsurpassed political influence. Britain’s pre-eminence in all these areas was, however, also being challenged in an unprecedented fashion, by the old powers, such as France, Belgium and Russia, by the new power of the USA, and, most ominously, by the newest power of all in Germany.

The rivalries first manifested themselves outside Europe, as the newer powers tried to create their own empires and Britain sought to maintain its supremacy. There was, in the second half of the nineteenth century, from Africa to the Pacific, a frenzy of land-grabbing. “Towards the end of the nineteenth century”, the historian Ronald Hyam observes in his book Britain’s Imperial Century 1815-1914, “European politicians felt themselves living in an era of world delimitation, ‘a partition of the world’ as Rosebery called it, from which, as Elgin (when viceroy of India) agreed, Britain could not stand aside because of her ‘mission as pioneers of civilization.'”

Between 1874 and 1902, Britain alone added 4,750,000 square miles and 90 million people to her Empire, ranging from numerous little Pacific Islands to Baluchistan, from Upper Burma to vast swathes of Africa. Britain, the Times declared, must continue expanding her empire because she could not afford “to allow any section even of the Dark Continent to believe that our imperial prestige is on the wane”.

Behind imperialist expansion lay venomous racism. “What signify these dark races to us?”, asked Robert Knox, Britain’s leading racial scientist, in his 1850 book The Races of Men. “Destined by the nature of their race to run, like all other animals, a certain limited course of existence, it matters little how their extinction is brought about.” Half a century later, the future American president Theodore Roosevelt wrote in his four-volume tome The Winning of the West that all must appreciate the “race importance” of the struggle between whites and the “scattered savage tribes, whose life was but a degrees less meaningless, squalid and ferocious than that of wild beasts”. The elimination of the inferior races would, he insisted, be “for the benefit of civilization and in the interests of mankind”, adding that it was “idle to apply to savages the rules of international morality that apply between stable and cultured communities”. Here was the grim, genocidal reality of Salisbury’s distinction between “living” and “dead” nations and the true meaning of the “encroachment” of the one upon the other.

If racial ideology justified imperialist expansion and, indeed, genocide, the very fact of empire seemed to confirm the reality of race. “What is Empire but the preponderance of race”, as the Liberal imperialist and prime minister Lord Roseberry asked. Even the anti-imperialist Gilbert Murray accepted that “There is in this world a hierarchy of races”, those that will “direct and rule the world” and the “lower breeds of men” who will have to perform “the lower work of the world”. “The brown, black and yellow races of the world”, the Times insisted in 1910, “had to accept that “inequality is inevitable” because of “the facts of race”.

Many politicians and intellectuals feared that the very existence of the “dead” nations created the conditions for conflict between the “living”. “Experience has already shown”, the distinguished Victorian historian WEH Lecky worried in his 1899 book Democracy and Liberty, “how easily these vague and ill-defined boundaries may become a new cause of European quarrels, and how often, in remote African jungles or forests, negroes armed with European guns may inflict defeats on European soldiers which will become the cause of costly and difficult wars.” Unless the world was carved up and parcelled out by the “white” nations, then the very weakness of the rest of the world would create a power vacuum that could, many feared, lead to conflicts between Great Powers.

Here were expressed the complex fears that emerged in the collision between racism and Great Power rivalry. (The US army recruitment poster above expresses even more clearly the entanglement of racism and imperialist fears.) In reality, while racial ideology provided the grounding for imperialist expansion, the real driver was economic and political necessity. For a burgeoning power, overseas colonies helped provide raw materials, cheap labour and new markets. They also helped impose political and military control. Britain, for instance, worried that French and German expansion in East Africa would undermine its sea routes to southern Africa and to India. “Its annexation by France or Germany and a seizure of a port would be ruinous” to Britain, wrote the Foreign secretary Lord Granville in 1884. “The proceedings of the French in Madagascar”, he added, “make it all the more necessary to guard […] our sea route to India.” What particularly worried British policy makers was the fear that the Suez Canal – so central to maintaining Britain’s trade routes and naval prowess across the globe – may be closed down in the event of war. It is “of supreme importance”, observed the colonial administrator Lord Lugard, who was to be Governor General of Nigeria during World War I, “that we should retain complete command of the only alternative and only feasible route in case of war.” Similar fears were expressed about German activity in southern Africa. “It seems that wherever there is a dark corner in South African politics”, Gladstone sardonically observed in 1884, “there is a German spectre to be the tenant of it”.

“From the Cape to Cairo”, a cartoon in, 1902

As the dominant global power, and as the nation with the largest empire, Britain was anxious to defend the status quo. Germany, as the rising power, and with only tattered shreds of an empire, was desperate to challenge the existing state of affairs. At the mid-point of the nineteenth century, Britain’s navy was as large as all the other navies put together. That exceptional power allowed Britain to control the world’s oceans and sea-lanes to establish “Pax Britannica”. By the end of the century, that supremacy was under threat as America and Germany, in particular, built up their naval prowess. In the half-century leading up to World War I, British naval spending doubled. Germany’s quadrupled, as it sought to play catch-up.

In attempting to displace British power and influence, and to create its own empire, Germany often adopted the more aggressive posture. In reality, however, Britain was no less militaristic or aggressive. Indeed, there was widespread concern within the political elite around the turn of the century that Britain was insufficiently militaristic to meet the new challenges. War, declared General Worsley, commander in chief of the army, in 1897, was a necessary remedy for social decadence; it was “the greatest purifier to the race or nation that has reached the verge of over-refinement”, an “invigorating antidote against that luxury and effeminacy which destroys nations as well as individuals.”

Britain had achieved its position of prominence only through deploying the kind of aggressive militarism, the prevention of which many today insist makes World War I a just conflict. Consider for instance the Opium Wars. In June 1840 a British expeditionary force sailed into China’s Pearl River and unleashed a barrage of cannon fire on coastal defences that barely existed. The battle lasted six hours. So began the First Opium War, a series of unequal military encounters lasting until 1842. A second Opium War culminated in 1860 with the looting and burning of the imperial pleasure grounds, the Yuan Ming Yuan, in the northwest suburbs of Beijing by British and French troops.

The Opium Wars were the nadir of British nineteenth-century gunboat diplomacy. Britain had built up a huge trade deficit with China, largely because of its insatiable thirst for tea. The East India Company began to fill that deficit by supplying opium grown in British Bengal. Opium had been consumed in China since the eighth century. But it was banned. In 1839 the Emperor cracked down on the trade, seizing the opium stock of British traders, and ordering them to bring no more into China. Four months later, the gunboats arrived. Britain launched a war in effect to enforce its right to be China’s pusher of choice.

The treaties that ended the wars were as scandalous than the war itself. China lost the right set protective tariffs or to collect custom duties on trade goods. Five “treaty ports” were established, in each of which parts of the city were set aside for foreigners to live and trade. Britain insisted on the right of extraterritoriality for all Western nations: each could run its own police force and court system, enforce its own laws and deal with any crimes committed on Chinese soil by its nationals under its laws, rather than those of China. Foreigners won the right to travel anywhere they wished to in China and to set up Christian missions without restrictions. Western navies won the right to sail at will on any Chinese waterway. Foreigners could import and sell opium. Hong Kong was ceded to Britain. And Britain extracted from the Emperor a large indemnity for all trouble that he had caused by standing up for his rights in the first place.

Today the Opium Wars are barely remembered in Britain. And when they are, they are seen only as an embarrassment, an exception to the true nature of Pax Britannica. In fact it was the kind of gunboat diplomacy that underpinned British imperialism throughout the nineteenth century.

Without understanding the background of nineteenth-century imperialism, it is difficult to make sense either of German militarism or World War I itself. Equally, understanding this background shows why there is little sense in treating the war in black and white terms of “good” and “bad” participants, or as a war against militarism or aggression. As historian Christopher Clark put it at the end of Sleepwalkers, his outstanding study of How Europe Went to War, “The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol. There is no smoking gun in this story; or, rather, there is one in the hands of every major character.”

None of the European powers wanted war. All had, over the previous half century, struggled immensely hard to prevent conflict, particularly in Europe. This was one of the reasons that war, when it did arrive, came as such a shock.

Equally, however, all recognized, with Salisbury, that the “seeds of conflict among civilized nations” had already been sown. The growing discord over the partitioning of the world led to the forging of new alliances between the Great Powers. At the time that Salisbury gave his speech, there was in place a multipolar system in which the Great Powers’ interests and rivalries were in precarious balance but which allowed for a large degree of give and take. By the eve of war, this had transformed into a bipolar system as Europe cleaved into two blocs. Britain established alliances with its traditional foes, France and Russia. Germany created the Triple Alliance with Austria and Italy. The new system was both more rigid and more unstable than the previous framework of informal checks and balances.

At the same time, the slow disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, and the resulting scramble to assert influence in the Balkans over which the Ottomans had lost control, brought imperialist frictions into the heart of Europe. Russia and Austria both looked upon the Balkans as its own sphere of influence. In the background stood Britain and Germany, neither of whom wanted the other to profit from any Balkan fallout. The kind of tensions that had previous rent southern Africa or the Middle East now expressed themselves within Europe itself.

Traditionally historians have divided between those who regarded World War I as the inevitable outcome of long-term structural factors, such as imperialist rivalries, the growth of nationalism and the ossified system of alliances, and those who viewed it as the result of immediate or contingent causes, and of individual mendacity or foolishness. More recently, there has been a recognition that both long-term and contingent factors played a role in fomenting war.

But however we understand the causes of the war, the fact remains that aggressive militarism was not confined to one side. Certainly, Germany had expansionist aims and a toxically racist culture. Britain, however, was not much different. We can only rewrite the conflict as a just war against German militarism by airbrushing out the reality of nineteenth and early-twentieth century imperialism.

Published 27 May 2014

Original in English

First published by New Humanist 2/2014 / Pandaemonium

Contributed by New Humanist © Kenan Malik / New Humanist / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.