Euroscepticism is about austerity, xenophobia, nationalism; but it is also about democracy. It is an argument about too much democracy, about there being one too many democratic forums in which one needs to engage and negotiate with others about the commons, laws, collective goods and policies.

There will always be democratic deficits, and there is no reason to be complacent about it. Yet, reducing the democratic question to a choice between Europe and the nation should be worrying for every democrat. Why would one question the European Parliament’s legitimacy or the value of arenas of public power instituted in the EU as such? No need to be romantic about democracy, but a distribution of power, especially over institutions that are partly dependent for their authority on institutionalizing democratic rights and procedures, is a key democratic good.

Photo: Spartak. Source: Shutterstock

Leaders of member states might not always like what is going on in the European arenas, as they do not always like what is going on in international, national and regional debates. Yet, democratic institutions are not there to make life easier for political elites, civil servants and business.

They exist to allow matters of common concern to be raised, discussed and negotiated, and to hold to account a wide range of practices, including decisions by politicians, tax evasion by business, use of racist language, welfare distribution and so on.

In this sense, the EU is an expression of a pluriversing of institutional democratic arenas in Europe. Here, democracy is not simply a matter of elections and judicial oversight of political life but also about what issues can be forcefully raised as matters of public concern. Multiple intertwined arenas allow for certain issues to be taken up that otherwise would disappear or never make it because of lack of time, conflicts of interest or changing political priorities.

Digital rights

Digital rights is one of these issues. It sounds like a technocratic matter but is actually about a wide range of concerns, including the limits of freedom of expression on the Internet; fear of abusive use of the Internet, ranging from bullying or identity theft to terrorism; the freedom of association; the right of privacy; and so on.

While the EU is not the only institution where digital rights are debated, shaped and scrutinized, it has played a key role in shaping the digital rights of citizens, as recently shown again in its actively engaging with the implications of the Snowden revelations on the US NSA surveillance programmes (such as PRISM) and UK surveillance programme codenamed TEMPORA. In many ways, and despite eurosceptics’ recurrent claims about the uselessness and pointlessness of the EU, the Snowden case has revealed the vitality of EU mechanisms to act, react and protect digital rights against intrusive and pervasive surveillance.

Further, as detailed in a report submitted to the EU Parliament LIBE Committee on mass surveillance programmes in EU member states (the introduction is reproduced here), a discussion of European surveillance programmes is more than just a question of striking a balance between data protection and national security. It also raises questions with regard to digital rights and the future of the governance of the web.

What has the EU ever done for us, concerning our digital rights?

Snowden’s revelations unveiled critical questions about our rights – the right of every person to respect for his or her private and family life, but also the duty of states to protect personal data. This aspect is high on the EU agenda, and Snowden’s revelations undoubtedly triggered reactions and actions in Europe and across EU member states, the significance of which should not be underestimated.

Three examples of EU action in that field are illustrative of EU activism for digital rights: the Data Retention Directive rejection, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) that was thrown out by the European Parliament, and net neutrality legislation.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) decided in April this year to invalidate the 2006 Data Retention Directive. This much-debated EU Law, which obliged communication data providers to store traffic and location data for later access by law enforcement, was implemented following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Its provisions required telecoms firms to store citizens’ communications data for up to two years. “By requiring the retention of those data and by allowing the competent national authorities to access those data, the directive interferes in a particularly serious manner with the fundamental rights to respect for private life and to the protection of personal data”, the ECJ ruled. The ECJ not only supports the argument that this Directive is a significant invasion of privacy, it also acknowledges that stronger protections against mass surveillance under European law are needed. A new data protection law is currently under preparation.

The ECJ decision furthermore demonstrates a democratic liveliness around these issues and a real capacity of the EU mechanism to answer EU citizens’ claim to protect their fundamental rights. The case against the Data Retention Directive was taken to the ECJ by an Irish human rights advocacy group Digital Rights Ireland (DRI). McGarr Solicitors, who represent DRI, welcomed the ECJ decision and declared the following:

This case is a profound statement of European values by Europe’s top court. The court has rejected the principle of mass surveillance of EU citizens without suspicion as incompatible with the Charter of Fundamental Rights. It will be up to individual member states to now ensure their domestic law is in compliance with the ECJ’s judgment.

The ECJ, which allows individuals, companies or organizations to bring cases before the Court if they feel their rights have been infringed by an EU institution, is one of the institutions that allows citizens’ claims to be heard and dealt with. The European Parliament is another such institution. Its powers and actions in the field of digital rights are also far from being vain and trivial. In fact, although Snowden’s revelations contributed to re-enforcing the need for parliamentary debates over these issues at the EU level, the EU Parliament already had a good track record of actions that favoured the protection of digital rights before the revelations.

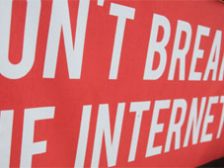

In 2012, the fight against the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) was already a fight for the protection of fundamental rights on the web. The intended purpose of ACTA as a multinational treaty was to establish international standards for intellectual property rights enforcement. The agreement aimed to establish an international legal framework for targeting counterfeit goods, generic medicines and copyright infringement on the Internet. The EU signed the agreement in 2012. Organizations representing citizens and non-governmental interests argued that ACTA could infringe fundamental rights including freedom of expression and privacy. The secret nature of negotiations excluded civil society groups, developing countries and the general public from the agreement’s negotiation process.

Critics, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Entertainment Consumers Association, described it as policy laundering. Several groups at the European Parliament, and The Greens in particular, campaigned against ACTA and on 4 July 2012, the European Parliament massively rejected the Treaty (478 votes to 39, with 165 abstentions).

There are now similar, ongoing discussions on the much debated negotiations surrounding the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), in which some MEPs denounce proposals relating to copyright, patent and trademarks despite the former rejection of ACTA and calls of civil society to protect EU citizens’ digital rights and ensure open negotiations in that matter.

Net neutrality and the future of Internet governance

What the ECJ decision and, prior to that, the rejection of ACTA by the European Parliament show is that the EU is democratically active on what is now widely referred to as “net neutrality”. The concept is believed to have been coined by Tim Wu, a Columbia law professor, in an article published in 2003 that argues that Internet service providers and governments should treat all data on the Internet equally and not discriminate or charge differentially by user, content, site, platform, application, type of attached equipment or modes of communication.

At the beginning of April this year, the European Parliament adopted in first reading the Regulation on the Single Telecoms Market, that includes important amendments to guarantee net neutrality and the principle of non-discrimination. This has been welcomed by numerous activists and civil society groups as an historic step for the protection of Net Neutrality and the Internet commons in the European Union.

The adopted text contains a rigorous definition of net neutrality and grants it a normative scope: the principle of “net neutrality” means that traffic should be treated equally, without discrimination, restriction or interference, independent of the sender, receiver, type, content, device, service or application. This wording is a direct response to the report of the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) on traffic management practices and a study, commissioned by the Executive Agency for Consumers and Health on the functioning of the market of Internet access and provision from a consumer perspective. Both were published in 2012, and showed that a significant number of end-users were affected by traffic management practices that block or slow down specific applications.

The European Parliament reminds us here that “these tendencies require clear rules at the Union level to maintain the open Internet and to avoid fragmentation of the single market resulting from individual member states’ measures”.

This parliamentary activism is part of a wider set of democratic actions on digital rights. For example, recently a two-day global conference on the future of the Internet was organized in Sao Paulo (23-24 April, Brazil). The aim of this NetMundial was to promote a global bill that guarantees the online privacy of users and enshrines equal access to the global network. The bill was introduced by president Dilma Rousseff in the wake of the NSA scandal, which revealed that Brazil was one of the primary targets of the US intelligence apparatus.

This conference was the first of its kind and clearly questioned the US predominance in Internet governance. The outcome of the conference was not what some had hoped: mass surveillance was not sufficiently denounced and the intention to produce a draft text to ensure rights to freedom of expression and privacy failed. Yet, like the European Parliament and the ECJ, it did contribute to making digital rights a public issue of concern that needs to be a matter of democratic action rather than left to intelligence organizations.

The political disconnection of domestic citizens and EU citizens

Sadly, national debates about the EU are far removed from this agenda, and very little is said about the positive actions of Europe in the field of digital rights.

So how are these issues echoed at the domestic level? In the UK, the manifestos published domestically for the EU elections display a striking silence. Not a single word on the protection of EU citizens’ data in the LibDem, Conservative or Labour manifestos for these elections. The UK Green Party is actually the only party that includes in its Manifesto a section on “protecting our Internet freedom” that reproduces the claims elaborated within the European Green Manifesto. The need for stronger protection of personal data, for the right to privacy and for strict net neutrality is also supported by the UK Pirate Party, which is presenting several candidates for the EU elections, including in the UK in the north west.

This silence is particularly striking in a country where the role of GCHQ in surveillance programmes has been strongly criticized and has provoked numerous outraged reactions. It is also striking when looking at the manifestos produced by the EU political groups to which UK parties belong (such as the European Conservatives and Reformists, the Europe of Freedom and Democracy group, the European Greens, the Socialists and Democrats Group and the Liberal and Democratic group, ALDE), as these manifestos do refer to the reinforcement of citizens’ privacy rights, the protection of personal rights and the need for more data privacy regulation as key challenges for the future of Europe.

This once again illustrates the discrepancies between priorities set by politicians for democratic debates at home and the debates that emerge in the European sphere. It is as if the areas of concern to UK citizens were, to a large extent, disconnected from their concerns as EU citizens.

This is worrying because the governance of the Internet affects us all, in many aspects of our lives: the way we access music and films, the way we express ourselves online, how much we all pay for these services. Yet, the EU’s activism on digital rights is also a sign that retaining multiple sites of democratic debate and policy-making in Europe is a democratic good rather than a problem.

As the recent decision of the ECJ about the “right to be forgotten” on the web reminds us, the governance of the Internet requires an Internet commons and currently the EU is key for ensuring that this commons is heard.