In March 2020, the Republic of North Macedonia became the thirtieth member of NATO, having changed its name from the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia in 2018 to overcome Greece’s veto. A long-delayed invitation to start negotiations for membership of the EU was expected to follow. On 17 November 2020, however, Bulgaria blocked the negotiation framework because of disputes over history, language and policies on ‘national identity’.

The US Department of State expressed its disappointment, as did EU representatives and leaders of member states. All appealed to the two countries to resolve their bilateral issues. But no quick and easy solution can be seen on the horizon.

The Bulgarian government’s decision was not surprising, given its populism and the history of similar examples involving North Macedonia. But in terms of the goal of long-term stability in South East Europe, it was astonishing. This goal will be impossible before the issue of North Macedonia has received a sustainable solution.

It is not Kosovo that poses the highest risk for the region, but North Macedonia. Kosovo was a Serbian ‘province’ and although the problem is acute, it involves only two countries. The case of North Macedonia, on the other hand, has multiple regional implications.

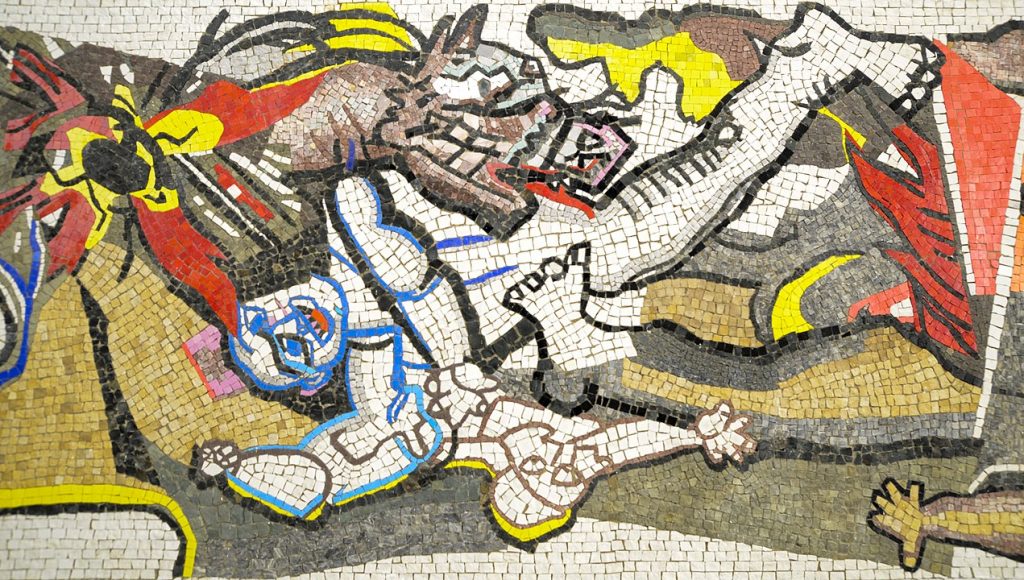

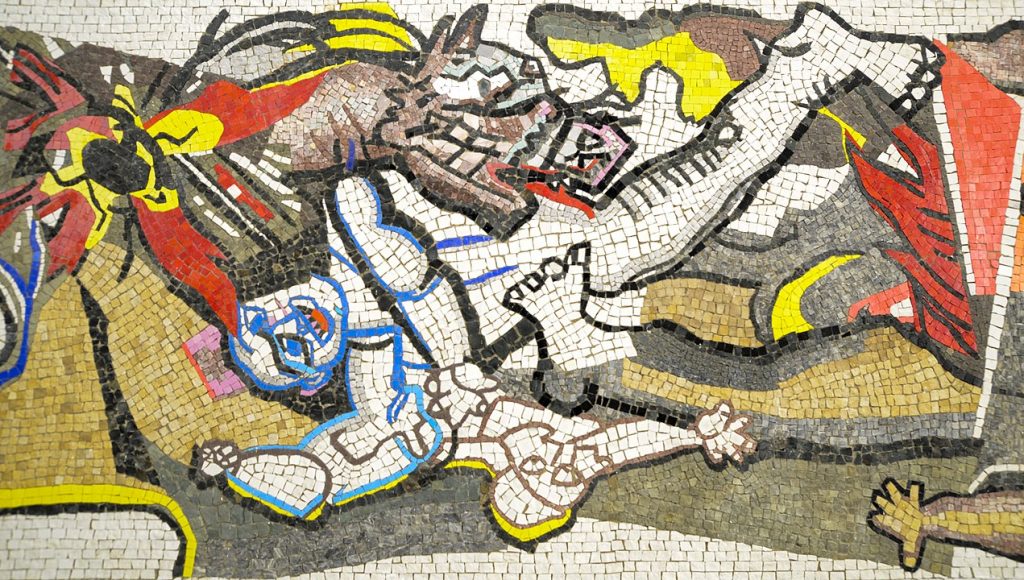

Mosaic by Petar Mazev in Memorial ossuary and museum of fallen fighters in the National Liberation War in Veles. Author: Dristovski. Source: Wikimedia

The ‘Macedonian question’

In a textbook published in 1977, Macedonia at the turn of the twentieth century was described thus:

The population was divided into nine distinct groups: Turks, Bulgars, Greeks, Serbs, Macedonians, Albanians, Vlachs or Kutzo-Vlachs, Jews and Gypsies … The Bulgarians used linguistic arguments to demonstrate that the Macedonian Slavs were indeed their brothers. Serbian anthropologists argued that their slava festival, also found among the Macedonians, made them Serbs. The Greeks sought to demonstrate that anyone in Macedonia under the authority of the ecumenical patriarch was Greek. Each nation thus used every conceivable argument to back its claims, and each could effectively be challenged … Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia all wished to acquire Macedonia or a major portion of it for three main reasons. First, it would enlarge the state and incorporate more nationals within it. Second, the acquisition of the Vardar and Struma river valleys and the railroads through them would have great economic advantages. Third, and perhaps most significant, whoever controlled Macedonia would be the strongest nation on the peninsula. For the great powers, this last concern was certainly the most important.

This description is an accurate account of how Macedonia was viewed and assessed at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries. During this period, the discourse on Macedonia produced what has since been referred to as the ‘Macedonian question’. At the turn of the twentieth century, Macedonia appeared not as a self-standing whole with its own political project, but as a space defined by the intersection of external viewpoints, first and foremost the political attitudes of its neighbours.

According to this discourse, the surrounding nations believed that Macedonia was a natural addition to their own completion; questions about history, language, ethnicity, and so on supported territorial ambitions. At the same time, Macedonia was seen as being imbued with special significance by the ‘great powers’ such as Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary and Britain. Whoever controlled Macedonia, they believed, could exercise control over the entire region.

Today, the idea of altering state borders is anachronistic. There is also no reason to assume that North Macedonia has preserved the strategic importance it was once supposed to have. And yet its neighbours’ attitudes are still reminiscent of the old discourse. Today, the neighbouring states challenge North Macedonia’s language, its history and all kinds of national symbolism.

What a full satisfaction of these claims would look like is hard to say. If such demands were met, North Macedonia would have territory and state institutions – but no language, no culture and no history. This would be a very exotic construct, and truly absurd. Yet this fantastic image has direct political and security implications for the region.

A divided body politic

A second set of risks results from the tensions between the Slavic and the Albanian communities. The Albanians disputed their status under the ethno-nationalist constitution of 1991 and for many years demanded changes. The constitution had given them a secondary political rank as a community that was not ‘constitutive’ of Macedonian nationhood, as was the case for the Slavic community. This ethno-constitutional arrangement led to a series of other discriminatory laws, political decisions and practices. In 2001, the conflict escalated into a short civil war. The Albanian communities did not, however, support a territorial separation and limited their demands to equal constitutional status.

It is fair to say that the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia avoided territorial disintegration because of the moderation of the Albanian communities. The state itself was weak and incapable of imposing a central political will. The conflict was resolved through international mediation led by James Pardew, dispatched by the US Secretary of State Colin Powell, and the EU representative François Léotard. The result was the Ohrid Agreement in 2001, a large-scale reform of the existing constitution.

Since then, FYROM/North Macedonia has experienced a succession of political crises. At times, these have developed along ethnic lines, as was the case in 2017, when an ethnic Albanian was elected as speaker of parliament. But other factors have also played a role, such as corruption, discrimination, traditional hatred, political radicalization, lack of control on immigration from Kosovo. This combination was responsible for the Kumanovo clashes in 2015, involving an armed Albanian group calling itself the National Liberation Army. The clashes led to dozens of deaths on both sides, many injuries to the police and subsequent terrorism trails.

More often than not, political crises have involved high-level political and institutional corruption. In 2015, an EU investigation pointed out ‘electoral fraud, corruption, abuse of power and authority … blackmail, extortion … criminal damage’. Ever since 2001, FYROM/North Macedonia has been on the brink of state failure or collapse, but has survived against all odds. North Macedonia is also in a difficult economic situation, with up to 20 per cent unemployment and a large informal economy. This economic crisis has only been deepened by the pandemic.

Finally, for the last twenty years the country has been sliding down the steep slope of nationalism. This symbolic war has diverted valuable social energy into transforming Skopje into a national museum. This kind of state propaganda goes on not just in the architectural space of the capital, but at all levels of policy, education and the media.

Museum of the Macedonian Struggle in Skopje Photo by Тиверополник, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

These factors mean that the state continues to exist as a divided and problematic political form. State collapse is not an imminent danger, as in 2001, but is a perpetual risk. Ad hoc diplomatic missions cannot produce a sustainable stabilization. Yet another Ohrid Agreement, or amendments to the constitution, or even a new constitution altogether, would not be sufficient. Something essentially different is needed.

Beyond Balkanization

It is in the interest of all the neighbouring countries to detach themselves from the ‘Macedonian question’ and start thinking in terms of the overall stability of the Balkans. The entire region needs to take the scenario of Macedonian disintegration very seriously. If that were to happen, the result would be two unviable semi-states or two stateless communities. Such a development would produce an immediate domino effect. None of the neighbours could avoid serious damage.

The redrawing of boundaries in this part of the Balkans has been periodically suggested by some western politicians, such as David Owen, former British foreign secretary and negotiator during the Balkan wars of the 1990s. However, no country in the region has the capacity to integrate large portions of North Macedonia’s population, economy and society, even if they wanted to, and even if the main international actors agreed, which currently seems improbable.

The risks can therefore be minimized only by North Macedonia’s accession into a large, regulated community. In the past, the Ottoman Empire and the Yugoslav Federation provided security guarantees and prevented outside forces from posing occupation rings around Macedonia – even if they also involved repression and assimilation policies. NATO provides defence guarantees but little in terms of societal stabilization and development. Full EU membership is the only way to open the path to a stable North Macedonia.

International mediators, leading EU members states and US missions should make a strong effort to convince Bulgaria to support North Macedonia’s integration process. This is not an easy task, since the current policy finds massive support among Bulgarians, rather like Greece’s demand that Macedonia change its name.

But it is not enough to force Bulgaria’s government to submit to outside pressure. Instead, international facilitation should promote a radical change in the language with which neighbours talk about North Macedonia. Both the Bulgarian and Macedonian governments must be persuaded of the simple truth that international integration is about guaranteeing peace and security, not about history, symbols, memories and popular emotions. Both governments should take it as their duty to replace the language of romantic remembrance by a pragmatic language of international security.

Giving North Macedonia a real chance for European integration would be a crucial achievement in dismantling the reality of Balkan balkanization, which finds a powerful expression in the highly questionable ‘Macedonian question’.