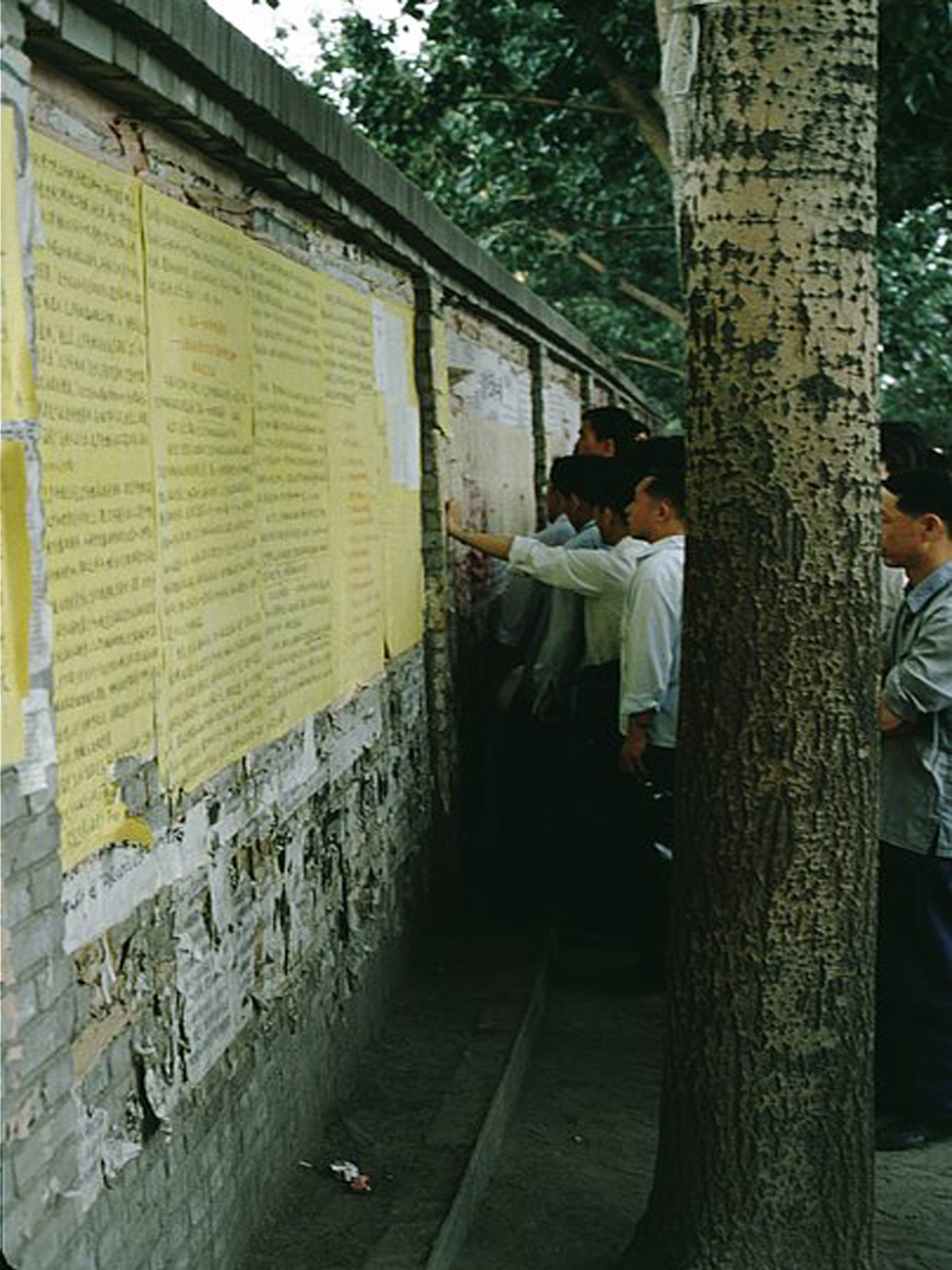

Walls are perhaps the most iconic and enduring images from 1989. The political imaginary of Americans and Europeans alike centres on one iconic photo: that of exuberant East and West Germans breaking down the Berlin Wall on the night of November 9th that year. The wall was the physical embodiment of Cold War division and authoritarian rule; its destruction reflected liberal aspirations for a world soon to be remade in the image of America and western Europe. Yet, for those of us who care to remember, in China we start with images of another wall. This one culminates not in a story of liberation, however, but in the violent drama at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

This story begins ten years earlier, in 1979, off the Xidan Road, today less than a block from the busy Xicheng subway station, when students and journalists put up critical posters of Mao, his ideological successors (the so-called Gang of Four), and the excesses of the Cultural Revolution more generally. Since these early posters were generally directed against Deng Xiaoping’s political and ideological enemies, while favouring his proposed economic reforms, authorities tolerated this so-called ‘democracy wall’ or ‘Xidan wall.’ As China jumped headlong into economic reform under Deng’s leadership, the demands and aspirations articulated by these anonymous postings on the wall changed too.

By the mid-1980s, this short block off Xidan road had become a busy hub for amateur journalists and student publications, which had begun to distribute privately published issues of magazines and newspapers. These publications often included explicit calls for both an end to one-party rule and political liberalization along western lines. The fact that authorities tacitly tolerated this so-called ‘underground press’ highlights the extent to which the Chinese Communist Party itself was divided on the issue of the country’s political future at the time. In the lead-up to the 1989 student demonstrations in Beijing, the ‘democracy wall’ became a site of activist mobilization. There, the leaders of student organizations mingled with factory bosses and (party-authorized) union heads, exchanged viewpoints, shouting out manifestos, pamphlets, and editorials via loudspeaker to audiences of thousands. All of this is to say that, in many regards, China’s lead-up to the ‘1989 moment’ mirrored that of Eastern Bloc Europe. Chinese demands for liberalization did not, however, end like post-Solidarity Poland. Whereas the wave of popular protest swept away the Soviet satellite governments of east-central Europe, 1989 in China ended with the violent removal of student demonstrators from Tiananmen Square by gunpoint.

Prophecies of imminent collapse notwithstanding, since 1989, China has emerged as the most significant challenge to the narrative of liberal universalism. Throughout the 1990s, liberal establishments in Europe and America seemed content to integrate nominally communist China into the economic institutions of the world market. China’s December 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization reflected a decade-long notion in the west that opening up the Chinese economy, and the rise of a wealthy, educated middle class would necessarily lead to greater demands for political freedoms.

In short, Western narratives about China throughout the 1990s hinged on the logic that capitalist development must end with liberal democracy. In hindsight, however, precisely the opposite seems to have occurred in the People’s Republic. Rather than being a political albatross on the Party’s neck, the legacy of Tiananmen, the chaotic aftermath of Soviet collapse, and the difficulties in bridging east-west divisions in Europe, has paradoxically bolstered the Party’s legitimacy in China. Indeed, public opinion surveys in recent years have consistently found that a majority of Chinese citizens are not only content with the Party’s leadership but broadly more optimistic about their personal future and that of their country relative to those polled in the West. The same surveys also found that Chinese people tend to be unsympathetic to proposals for major shifts in China’s current political framework. Moreover, positive opinions regarding one-party rule in China seem to have consistently grown in the last two decades.

In the Party’s own triumphalist narrative, 1991 and 1999 stand out as two watershed moments. From Beijing’s perspective, the anarchy of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Yeltsin’s cynical crushing of parliamentary opposition, furnished a perfect counter-narrative to June 4th, 1989. As Russia, China’s former Cold War arch-rival, sank into economic freefall, rampant corruption, and a period of geopolitical irrelevancy, China’s communist party leadership was able to guarantee political stability and engineered three decades of uninterrupted economic growth.

As one scholar of modern China has stressed, in the aftermath of Tiananmen, and the end of the Soviet Union, the Chinese Communist Party extended to the country’s nascent middle class a kind of Faustian pact. In return for unquestioned political control, the party-state promised to deliver stability, unrestricted economic freedoms, and continued economic growth. More recently, this story about China avoiding the ‘chaos trap’ of liberal democracy has received something of a second wind with the election of Donald Trump in the United States and the post-Brexit fallout in the UK. As Chinese state media never tires of pointing out, the divisiveness and unpredictability of western populist politics could never happen under one-party rule. In a recent forum on comparative economics at Beijing University, a Chinese professor of history tellingly cited the 12th century conservative Chinese historian and philosopher Sima Guang at an American counterpoint who raised the prickly issue of political reform in the PRC, ‘A century of tyranny should always be preferred to a single day of anarchy.’

A future historian recalling Chinese nationalism since the founding of the People’s Republic might look at 1999 as the year in which the emerging Chinese middle class became disillusioned with liberal universalism. On the night of May 7th 1999, American planes intervening in Serbia, as part of a wider NATO operation to halt Serbian offensives in Kosovo, bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. In the political drama that followed, the U.S. and China clashed over official narratives of the sequence of events, with the Chinese maintaining that the bombing was deliberate. Overnight, the largest mass protests in China since 1989 erupted across the country targeting American-owned businesses and official consulates alike. The bombing and subsequent nationalist uproar should be seen as a continuation of a broader disenchantment with western liberalism emerging since the collapse of the Soviet Union. As at least one Chinese dissident-turned-nationalist has argued, the political enfeeblement of Russia after 1991, coupled with America’s perceived arrogance in the handling of the embassy bombing served as something of a political re-awakening.

Ruins of the Radio Television of Serbia, destroyed during 1999 NATO bombing in Belgrade, Serbia, FR Yugoslavia.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

In the aftermath of 1999, many of the dissidents who remained in China after the Tiananmen Square crackdown came round to the Chinese government’s point of view that universal liberalism was, in fact, a thin guise for the preservation of American geopolitical power.

From the End of Walls towards a World of Alternatives

Ivan Krastev has stressed that the ‘politics of imitation’ which Eastern Europe pursued vis-à-vis the West after 1989 was predicated on the idea that western Europe possessed the viable path towards economic prosperity and lasting political stability. The western counterpart to this triumphalist narrative of liberal universalism hinges on America and western Europe continuing to see themselves as representing the ‘normative path’ of political-economic development. The very promise of 1989—that the division between east and west could be eradicated altogether—was thus predicated on two interdependent conceptions of the European future. Firstly, the peoples of former socialist states had to believe that the path of liberal democracy and the free market was desirable (or even the only viable alternative). Secondly, the west must continue to see itself in normative terms as the logical endpoint of political-economic development. In other words, the political project of bridging eastern and western Europe inaugurated in 1989 could only ever have been the voluntary absorption of the east by the west.

Thirty years on: Germany’s unfinished unity

As of this year, Germany has been united for a longer time than the Wall and its barbed wire stood. Yet despite 30 years of the Solidarpakt, social differences have not been evened out as hoped, and the division is tangible in political leanings as well, Claus Leggewie writes.

In this regard, German reunification is a telling microcosm for the disillusionment of both sides with the narrative of western ‘normativity’ and eastern ‘deviance’. Indeed, the emergence of the nationalist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and PEGIDA in eastern Germany raises the spectre that German reunification has already ended in failure. As

Claus Leggewie has very recently noted, the populist ire directed by many in former East Germany against ‘Brussels’ and the EU has elements of ‘post-colonial aversion.’ While scholars have for some time emphasized the absence of any meaningful confrontation with the Nazi past under the German Democratic Republic as a cultural explanation for the intensity of right-extremism in former East Germany, we should also bear in mind the economic fallout from the unification of East and West Germany.

Neue Wache – After German reunification the Neue Wache was inaugurated on the National Day of Mourning in 1993 as the “Central Memorial of the Federal Republic of Germany” with the mourning pieta by Käthe Kollwitz in Tessenow’s reconstructed “monumentally void interior hall”.

Photo by Alexander on Flickr.

This so-called Kränkungsthese in German sociological literature stresses the destructive and quasi-colonial takeover of former East German state industries by West Germany after 1991. The Treuhandanstalt founded after reunification effectively assumed control of the most significant segments of the former East German economy, notably mining, steel, and key manufacturing sectors with the proclaimed goal of ‘promoting competitiveness.’ By the late 1990s, however, such ‘trustee economics’ in East Germany had effectively liquidated mining and steel (previously among two of the largest employment sectors in the GDR) and privatized the largest remaining manufacturing firms, often subsuming them under their more competitive West German counterparts.

It is difficult to overstate the human impact of this merger process. In ways that mirrored the de-industrialization of northern England under Thatcher, virtually an entire generation of East Germans found themselves excluded from a new world of market capitalism in which their professional skills were rendered obsolete by economic reunification. The subsequent internal migration of hundreds of thousands of predominantly young and/or educated East Germans westwards further exacerbated such anxieties that 1989 had, in fact, ushered in a new age which rendered a significant proportion of the former GDR’s population economically superfluous.

From East Germany, parallels can be drawn across Europe and America, with automation and outsourcing displacing comparable demographic groups in Italy, France, the UK, and America. The political articulations of such pervasive economic anxieties over human obsolescence may occur under the rubric of Brexit, the gilets jaunes in France, Five Star and Lega in Italy, AfD in Germany, or Trump’s vision of ‘America First’ and the proposed border wall with Mexico. In this regard, it is intriguing to consider that, in the three decades since 1989, the West was not only unable to fully integrate eastern Europe, but rather eastern anxieties about economic obsolescence have actually been subsumed by the west. These anxieties have, in turn, been rearticulated via the political vocabulary of Islamophobia or ‘nativism’ into a new pattern of grassroots political mobilisation directed against notions of western liberalism. Indeed, while popular imaginaries of revolutionary moments (of which 1989 is a recent example) cast them as clear points of rupture — event horizons of political, social and cultural tumult from which societies emerge radically transformed — we should also keep in mind that the aspirations and optimism unleashed in moments of political transformation rarely persist beyond the initial revolutionary moment.

After nearly a decade of financial austerity in Europe, China has now emerged as something of an economic alternative for the ‘middling’ states of east-central Europe. Breaking ranks with its Franco-German counterparts, Italy has already signalled its willingness to sign onto China’s multi-trillion dollar ‘belt and road’ initiative, which aims to create a direct land route linking markets in east Asia and western Europe. Similarly, Steve Bannon’s efforts to engineer a pan-nationalist political movement in Europe have seemingly also floundered in the Czech Republic and Hungary. Both Viktor Orbán and Andrej Babis have, it seems, rebuffed Bannon in favour of future investments from Beijing. Moreover, all of this is occurring amid a wider turn in east-central Europe towards illiberal and authoritarian governance that increasingly resembles Putin’s Russia.

In this context, it may no longer be useful to think of the world along a continuing east-west divide. Instead, the optimism and self-belief necessary to sustaining the image of a universal western liberalism has largely been shattered. From the singular imaginary of a world without walls that followed the end of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the first decade of the 2000s gave way to geopolitical frustrations and economic crises. In the aftermath of the triumphant liberalism of the 1990s, we are perhaps entering a renewed period of alternatives, albeit not in the oppositional sense that characterized the Cold War. Instead, the political promise of liberalism as the eventual nomos of the world has largely given way to a universal acceptance of what we might call ‘capitalism with caveats.’

Understood this way, the Chinese alternative promises something of an ersatz populism whereby capitalist logics of GDP growth replaces mass political pressure from below as a means of legitimating authoritarian rule. In a similar vein, the ‘oligarchic clientelism’ of Putin’s Russia is seamlessly adopted by aspiring authoritarians the world over, which constitutes a political alternative, one which avoids the potentially de-stabilizing effects of the free market. The Cold War made it difficult (if not impossible) to conceive of genuine political alternatives detached from the communist-capitalist binary. The decades that followed 1989 showed that it was in fact possible to separate liberalism from capitalism, and to embrace certain elements of the free market without having to accept liberal democracy. Much of the present perception regarding a ‘crisis of liberalism’ may stem then from our (re)entry into this world of alternatives.