Kiril Petkov’s reformist government in Bulgaria has just clocked in four months in power. Amidst low vaccination coverage, Russian influence, and an ongoing war on corruption, there are few reasons to celebrate, aside from the fact there is a government at all.

‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ The opening line of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is nowadays a fitting cliché with which to launch a piece on Bulgaria. These are particularly tense times in the capital Sofia, and while many aspects of this trouble are common to other nations – war, pestilence and economic woes are by no means our exclusive concern – the circumstances determining the current Bulgarian condition are not. Many are locally specific and cannot be righted by outside pressure – not exclusively anyway.

Take the country’s politics. The young reformist government of Prime Minister Kiril Petkov has just clocked in one hundred days in power. There are few reasons to celebrate, aside from the fact that there is a government at all. It took two abortive attempts to form a governing majority and almost a year of consecutive caretaker Cabinets before the current rickety edifice was put together under the guidance of President Rumen Radev – a former Air Force general who managed to win a second term in the middle of the country’s worst parliamentary crisis.

Тen years of centre-right party GERB’s unrelenting monopoly on power raised expectations that Kiril Petkov would deliver not merely relief but a complete, and long overdue, overhaul of the system. His predecessor (not counting caretaker PM Stefan Yanev, another military man) was Boyko Borissov, a burly ex-fireman, karate coach, professional bodyguard and security company owner. For many years Borissov enjoyed strong support from the European People’s Party and its German pillars – Angela Merkel’s CDU and its Bavarian counterpart CSU.

That Borissov speaks no languages other than Bulgarian (some uncharitable observers might be inclined to problematize his use of Bulgarian too) was of lesser concern to his compatriots than the pervasive aroma of grand corruption that wafted from virtually all his dealings. A skilled populist, he managed simultaneously to ward off any meaningful challenge to himself and his grip on power, to reassure Bulgaria’s European partners of his loyalty, maintain impressively consistent levels of popularity and establish a staggering clientelist network. He seemed, for some time, unassailable.

Clash of the titans

Yet, as they say, you can fool some people some of the time, but never all people all the time. Borissov’s reign was marked by scandals regarding misuse of public funds, the syphoning off of European money, extortion of businesses on a scale hitherto unknown, conspiracy to unlawfully undermine opponents and other misdeeds too numerous to mention. Eventually, having enjoyed an almost supernatural relationship with television cameras, his grip on media started loosening. People talked. Some came out with shocking revelations. The Teflon started peeling off.

At the centre of all this turmoil stood a General Prosecutor’s Office whose position in Bulgarian public life is hard to overestimate. The holder of this office is himself (only men have ever held it) immune to prosecution or removal. He is elected for a seven-year term and, once he is in, it would not be an exaggeration to say that he is responsible only to the Almighty. Combine his power with insalubrious business- and political interests, and you will get some idea of the nature of the beast that Bulgarian opposition and reformist leaders were, and are still, facing.

Boyko Borissov at an EPP summit in 2009. Photo by the European People’s Party via Flickr.

Borissov’s unprecedented run – he is now Bulgaria’s second longest serving PM – came to a grinding halt in 2020 when he fell out with another ‘heavyweight’, the cigar-toting gambling businessman Vasil Bozhkov, once the country’s richest man. ‘The Skull’, as Bozhkov is popularly known, had allegedly made a habit of paying Borissov off in order to be allowed to operate various betting and gaming enterprises. Needless to say, he is in tax arrears to the tune of hundreds of millions of euros. Accordingly the Interior Ministry and the Prosecution, allegedly in coordination with Borissov, wrested control of Bozhkov’s business and seized some of his assets. In any case, The Skull came out second best. He fled to Dubai and told all. His allegations in turn set in motion a chain of events that brought about Borissov’s resignation.

Simultaneously, another shadowy businessman – Delyan Peevski, virtual media monopolist and Borrisov ally – was declared by the US government to be running afoul of the Magnitsky anticorruption legislation alongside Bozhkov, having exerted control over Bulgarian institutions and political process while using influence peddling and bribes to protect himself from public scrutiny. These events played out in the background of an already intense war of attrition between Borissov and President Radev. An ambitious novice, Radev had started out at a disadvantage but managed to claw his way into the game on the back of considerable centre-left support. Street protests ensued. For Borissov, the writing was finally on the wall.

If ridding the country of Borissov was one thing, forming a workable majority to run it and reform it was quite another. The GERB regime had been around for so long, and its influence on politics had been so corrosive that the elections that followed resulted in a deeply fractured parliament. By the time of Borissov’s downfall, the Bulgarian Socialist Party was a political and demographic shadow of its previously formidable self. Democratic Bulgaria, an unlikely combination of Greens, Conservatives and Liberals, wielded limited influence as the mouthpiece of the urban middle class – hardly a foundation for mass political support in Bulgarian society.

Another newcomer collective, the populist party There Is Such a People, established by former television personality Slavi Trifonov was, and still is, an enigma in terms of ideology. Beyond hate for Borissov and sometimes radical nationalist pronouncements, theirs was a rather blurred political physiognomy. In any case, it was their intransigence that torpedoed the first post-Borissov attempt to form a government. Consequently, for most of 2021, President Radev was in charge, having formed a one-size-fits-all caretaker Cabinet. Sadly, the second attempt at finding a stable majority fell through too.

A perfect storm

The sudden entry into the fray, deus-ex-machina-like, of two caretaker Cabinet members broke this political impasse. Young Harvard-educated Kiril Petkov and Assen Vassilev, respectively Economic and Finance Minister, put themselves forward at a very opportune moment. Despite the two having had no time to register a party, and despite the former having rid himself of Canadian citizenship in rather hurried circumstances – dual nationality is a no-no in Bulgarian politics – they rode the crest of a popular wave at the third electoral try of the year. Radev lent critical support.

In the end, the tandem managed to hammer out a coalition excluding GERB, the largely ethnic-minority-supported Movement for Rights and Freedoms (a longstanding political power brokerage and source of both cronyism and gross corruption) and the extreme nationalist Rebirth party. Having donned this shining armour, however, they rode into what became a perfect storm.

Rarely has a government so young, so inexperienced and so dependent on an unstable parliamentary majority been in such a fix. Little of the current crisis, however, can be attributed to Petkov’s and Vassilev themselves. The circumstances have been lamentable. Several elements stand out in particular. One is undoubtedly the ongoing pandemic. Another is the steeply rising price of energy and attendant inflation. Bulgaria is highly dependent on Russian hydrocarbons and nuclear fuel, more so than other nations, and has no immediate access to alternative supplies. Yet another factor is the ongoing struggle between government and General Prosecutor Ivan Geshev, whose obdurate resistance to reform and blind defense of indefensible practices has attracted the attention of Laura Kövesi, the first European Chief Prosecutor. A brief look at each will help clarify the picture.

International response to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic was uneven at best, and oftentimes muddled. Bulgaria, like many nations, made a meal of its response – so much so that it now holds the tragic distinction of having one of the world’s lowest vaccination rates and correspondingly, one of the worst per capita mortality records. Why would a country with reasonably good record of immunizing against disease falter so badly? What went wrong?

Vaccine populism

Many things had been going wrong for quite some time. The pandemic revealed rampant populism in politics, the inability of government to stick to a consistent plan of action, critically low levels of public trust in institutions, rampant disinformation, long-standing corruption in the acquisition and distribution of medical supplies and an inefficient and low-reaching healthcare system. In short, the pandemic threw into sharp relief the vulnerabilities of a society divided and a government ill-prepared to cope.

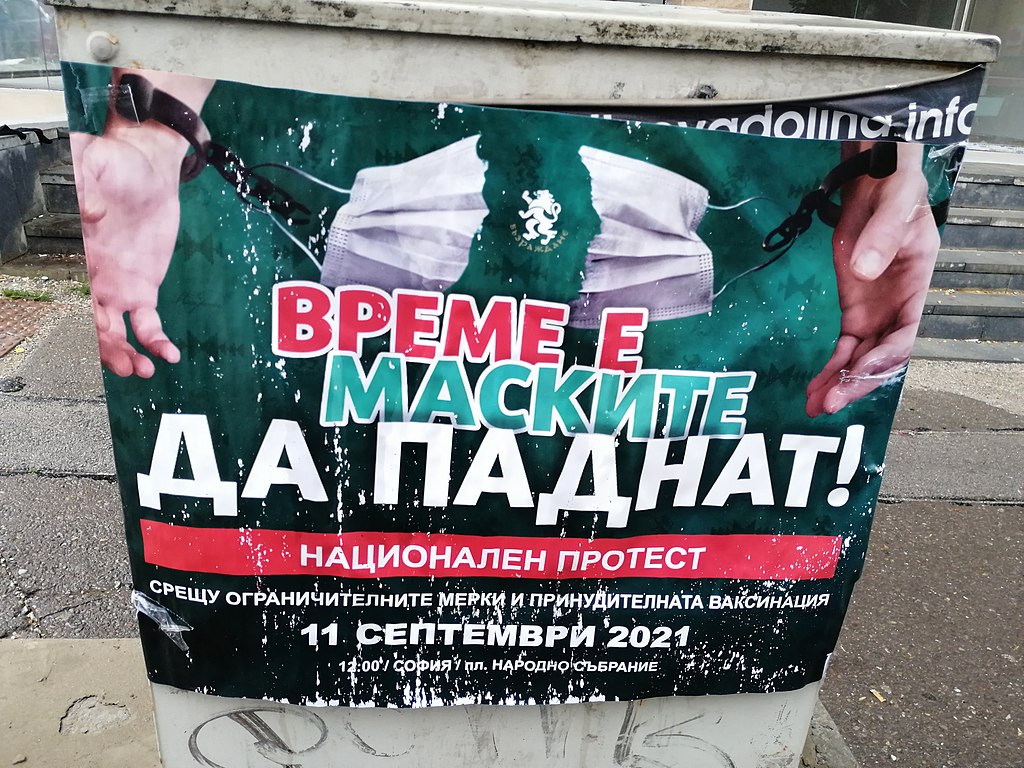

A poster of the ultranationalist Vazrazhdane party expressing opposition to mask mandates, lockdowns and compulsory vaccinations in Bulgaria. Photo by Oleg Morgan via Wikimedia Commons.

As of 21 March, 2,047,346 people in Bulgaria have undergone the full course of Covid-19 vaccination. 711,024 have received a booster shot. Depending on the total population count (there are minor discrepancies here) this constitutes a vaccination rate of between 29.4 and 33.5%, one of the lowest in the world. There have been over 36,000 deaths1. Early indications had suggested a more optimistic outcome. The Borissov government had at least been quick off the mark, putting together a crisis committee and adopting some harsh measures that warded off the worst effects of the first wave of infection. Gradually, however, things came unstuck.

Ever the populist, Borissov did not take any firm stance against antivaxxers. Senior medical figures publicly railed against the supposed ill-effects of the various vaccine brands. Theirs were portrayed as an ‘equally valid opinion’ and the legitimacy lent by endless media appearances eventually eased their way into national politics. Borissov also gave in to pressure from various business associations, especially in hospitality, and relaxed measures to limit the spread of the virus. His status as final arbiter in various national disputes – classic trope a of personality-driven politics – obviated a more structured, scientific approach to managing the crisis.

The deluge of false news and gross manipulation of public opinion in Bulgaria emanated, at least in part, from Russian ‘troll factories’. Talk of ‘immunization genocide’ stirred people who already had an extremely poor opinion of national politics and deep-seated mistrust of authority in general – the result of a post-Communist transition that divided the citizens of a traditionally egalitarian country into ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. Unsurprisingly, studies have shown a significant overlap between the less privileged social strata and those who tend to believe in conspiracies.

Russian sabotage

Dependence on Russian hydrocarbons is not unique to Bulgaria, nor was the failure to heed longtime warning signs that the Kremlin wields energy as a geostrategic weapon. What is of particular note is the scope of Russian influence on Bulgarian politics and the extent to which energy diversification has been sabotaged by the Russian energy lobby in Bulgaria. Borissov’s entire term in power was spent trying to appease Moscow while staying loyal to Berlin, Brussels and Washington. A key part of this balancing act involved managing various energy projects.

Gas is relatively unimportant to Bulgaria in local terms. Even though the country gets 70% of it from Russia, gas constitutes a mere 14% of energy in the mix. Petrol is another matter altogether. The Lukoil refinery near the Black Sea port of Burgas alone processes 60% of fuels sold in the country. Nearly 100% of Bulgaria’s crude oil comes from Russia. Another form of dependence comes with nuclear energy. The Kozloduy power plant in the north of the country utilizes Russian fuel and relies on Russia to process waste. A projected second plant in Belene has been on and off the agenda for decades.

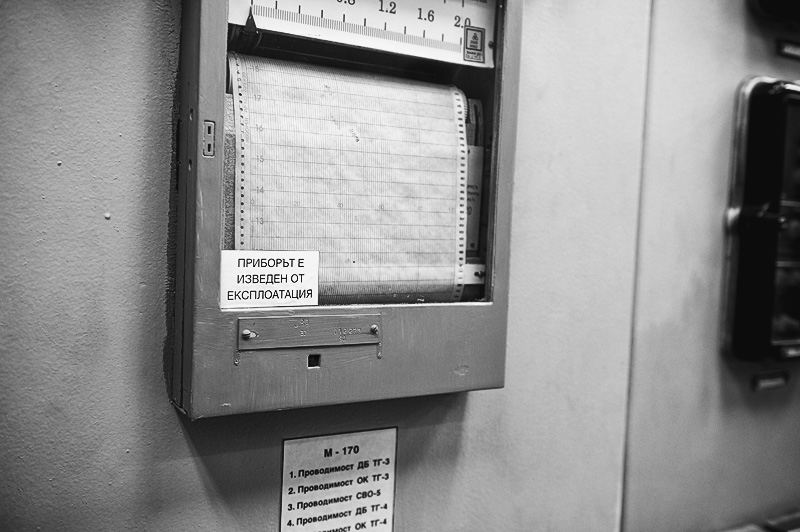

Obsolete instrument in the control room of the ‘dead’ Units 1 and 2 of the Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant. The notice reads: ‘this instrument has been put out of use’. Photo by Yovko Lambrev via Wikimedia Commons.

The Petkov government has been far more decisive than Borissov’s in reducing Russian energy dependency to manageable levels. A proposed interconnector to Greece is being rushed to completion, which will provide access to cheap Azeri gas and thus loosen the Gazprom noose. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, deputy PM and Finance Minister Asen Vassilev said that Bulgaria would invest in nuclear energy, and the country supported a French bid to declare nuclear ‘green’ in view of the EU’s impending – and profoundly transformational – Green Deal. Current contracts will be honoured, but no new business will be conducted with Gazprom until the war in Ukraine is over.

Over the past year, the energy crisis has attracted two-digit inflation. Bulgaria’s bitter experience in 1997, when 1 US dollar was exchanged for 3000 lev, left a deep scar. The Petkov government has attempted to alleviate the effect of high energy prices by borrowing money and raising salaries, thus contributing to inflation. At the same time, the Bulgarian recovery and resilience plan proposed to the European Commission by the Yanev caretaker Cabinet was at first rejected and took months to be amended. A final version was only approved on 25 March.

As if a pandemic, steep energy prices and inflation weren’t enough, the Petkov government faces two other intractable issues: a massive migration inflow caused by the Russian attack on Ukraine and an increasingly bitter fight with the General Prosecutor’s Office. Despite repeated warnings that Bulgaria lacks the infrastructure and integration capacity to deal with large-scale movements of people, the GERB administration did nothing to improve the situation. The Syrian civil war produced refugees who weren’t welcomed here, not by the state anyway.

Struggle to the end

The response to Ukrainian immigration has been markedly different, yet despite emergency measures enacted by the current government, infrastructure and administrative capacity are still lacking. As with the Syrian crisis, the brunt of responsibility is being borne by volunteers, of whom Bulgaria has every reason to be proud. Not so with its judicial system. Two years passed since Vasil Bozhkov’s original allegations of gross corruption. The Prosecution failed to pursue the matter and pretended no such case existed.

Things came to a head on 17 March when ex-PM and current leader of the opposition Borissov was detained and served papers for an impending investigation into the Bozhkov claims. Borissov, who only days earlier had been reelected leader of GERB with 100% of the vote, naturally chose to portray his arrest as political repression. A European People’s Party delegation rushed in to investigate whether their man was being handled improperly. GERB party faithful gathered outside Borrisov’s home and demanded the government’s resignation.

Yet again, the prosecution ducked and dived. When Interior Ministry men brought in evidence of wrongdoing on the part of Borissov’s ex-Finance Minister Vladislav Goranov and former government speaker Sevdalina Arnaoudova, no one was there to meet them and receive the files. Belatedly, a prosecutor was assigned to ‘review’ the case. The brouhaha attracted European attention from a different source, too: when asked her opinion, European Chief Prosecutor Laura Kövesi limited herself to a laconic ‘no comment’. She could barely hide her displeasure with Geshev.

In spite of criticism of the timing and method of pursuing Borissov, Petkov has vowed to press on. Additional evidence is being gathered of misappropriation of European money. When Petkov himself volunteered to give evidence, GERB struck back with allegations of misconduct on the part of Deputy PM and Finance Minister Asen Vassilev. The latter denies any. One is left with the impression of a political Armageddon – a struggle to the end between Bulgaria’s deep state, beholden to criminal and Russian interests, and a new generation of pro-Western leaders hell-bent on finally severing that connection.

Whether this is an accurate assessment of the situation is still being debated by the talking heads of Sofia. President Radev’s role in all of this is yet to play out. The war in the Ukraine has opened new fissures in the ruling coalition as some of its constituents support arming Ukraine against Russian aggression and other oppose it vehemently. The government is not faring so well in the polls – perhaps understandably given the multitude of challenges it faces. In any case, there seems to be some light at the end of Bulgaria’s tunnel. For clichéd as Anna Karenina’s opening line may be, its closing paragraph is frequently forgotten. For many а Bulgarian nowadays, tense as it is, ‘life […], every minute of it, is not only not meaningless, as it was before, but has the unquestionable meaning of the good which it is in my power to put into it!’ Hopefully, lasting change for the better is on the way.

See https://coronavirus.bg/ (last accessed on 4 April 2022).

Published 29 April 2022

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Yavor Siderov / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Maia Sandu came to power in Moldova by promising social unity. But as her popularity declines, she and her party may be reverting to divide and rule. Russian interests in destabilizing the country are real but of limited impact. The greater threats to democracy in Moldova are endogenous.

Two decades of speculative building and misuse of earthquake funds set Turkey up for disaster. Erdoğan’s AKP failed to plan or react, but will do anything to hang on to power.