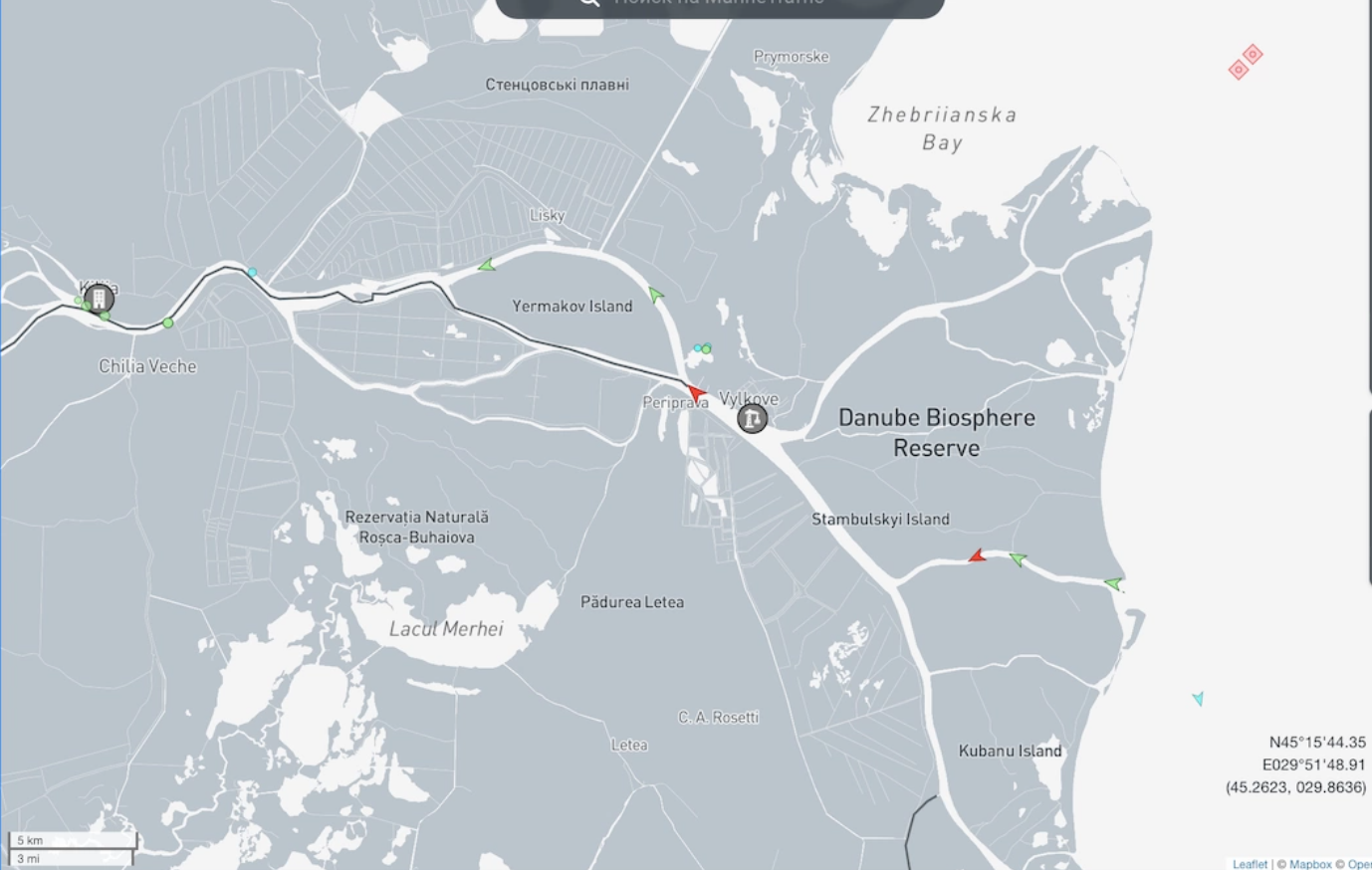

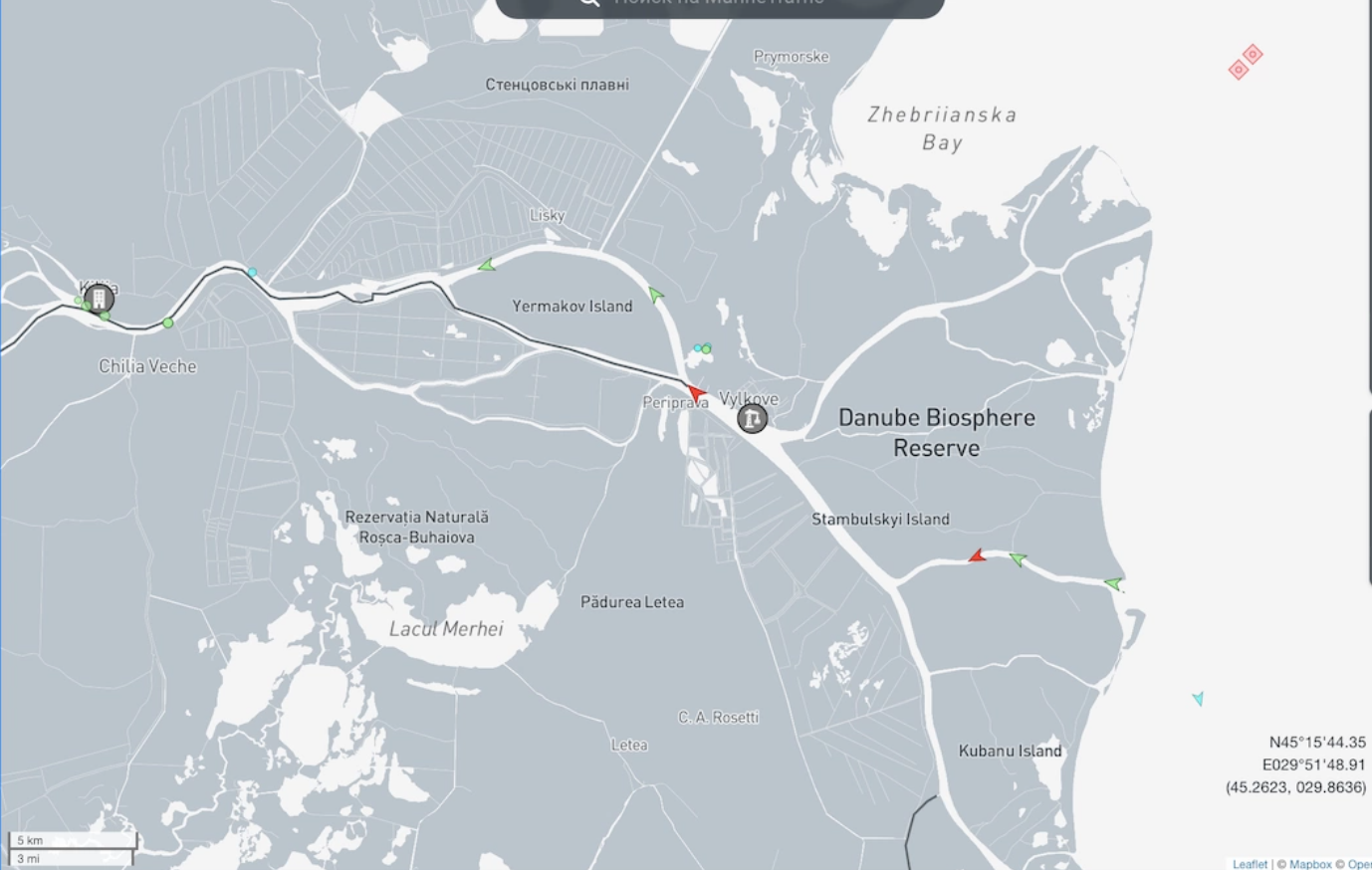

There is a remarkable place on the border between Ukraine and Romania — a maze of waterways, lakes, canals, and islands that together form a unique ecosystem spanning 7,322 square kilometers. This entire area, called the Danube Delta, is protected by virtue of its status as a UNESCO transboundary biosphere reserve.

On the Ukrainian side, the reserve is known as the Danube Biosphere Reserve, and on the Romanian side as the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve.

The Danube Delta is the largest delta ecosystem in Europe and plays a crucial role in water purification. It provides habitat for approximately 350 species of birds that use the delta for migration, wintering, or permanent residence. In addition, the reserve is home to more than 100 species of fish, including sturgeon populations.

Moreover, the delta serves as a vital refuge for endangered species, including the European mink, wild cat and otter. Its diverse and rich ecosystem supports a wide range of flora and fauna, making it one of the most important protected areas in Europe.

After the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, this natural habitat became threatened by the war and the increased naval traffic it brought to the region. This is the story of that impact, but also of the solutions that people on both the Ukrainian and Romanian sides of the Delta are working on to protect this area. From small communities documenting plastic waste, to researchers raising alarm bells, from actions that can be undertaken immediately to ideas that can only be implemented after the end of the war, different responses show the many nuances of the situation, as well as the people’s determination to protect this wild part of nature.

In Romania and Ukraine, the Danube Delta Is Hurting. Can We Do Anything to Heal It? is a cross-border investigation by Rubryka (Ukraine) and Scena9 (Romania) that explores current environmental challenges in the Danube Delta biosphere in both countries (some aggravated by Russia’s war in Ukraine), as well as potential solutions, for the short and long term.

The Danube is one of the largest rivers in Europe, and its attractiveness for shipping is immense. Through here Ukrainian grain is shipped to countries all over the world, especially in Africa. This is important both as a source of income for Ukraine and as a source of precious resources for the countries recieving the grain. The Sulina Canal, one of the Danube branches on Romanian territory, flows into the Black Sea and is primarily used for navigation. Since the early 2000s, Ukraine has sought to use another branch, Bystre, which lies within its own territory, for shipping.

When news of the construction project became public, it sparked widespread concern and opposition. Between May and October 2004, more than 50,000 organizations and individuals from 90 countries rallied to protect the Danube Biosphere Reserve. International bodies, including the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention, the Commission of the Espoo Convention, the European Commission, and the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube all recommended suspending the project.

Despite these efforts, construction proceeded, though the canal never operated at full capacity. The Bystre mouth required constant dredging and clearing of silt to allow ships to pass, but the maintenance costs were prohibitively high. Ultimately, the project was deemed unsustainable and was canceled due to these operational and financial challenges.

With the start of the full-scale war, the need for sea transportation of goods resurfaced. By early 2023, Ukraine had almost doubled the depth of the Bystre mouth, which may have significant consequences for the surrounding ecosystems.

Dredging works

Dredging works in the Bystre estuary were conducted twice in 2023, deepening the mouth from a ship draft of 3.9 meters to 7.2 meters. However, such use of the river can have an extremely negative effect on the environment. The dredging process essentially ‘sucks’ the silt from the riverbed, causing mussels, worms, crustaceans, and algae to disappear along with the sand. The entire food base that existed for local hydrobionts is being destroyed. What could be the consequences?

To determine the exact effects, field tests must be conducted. Currently, due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, access to the reserve at the Bystre mouth is impossible, and even scientists from nature protection institutions cannot reach these areas. However, we can look at a similar case on the Elbe River in Germany, where dredging was also performed. An article by the WWF Foundation discussing the deepening of the Elbe in the summer of 2020, explained that, in addition to harming hydrobionts, deepening can lead to the degradation of the river itself. Here’s how it works: as the channel deepens, the water flows faster, increasing the erosion of the banks. As a result, the banks collapse and the amount of silt increases:

‘Shallow areas become silted up and dry up. Entire side arms are silted up. But it is precisely these water areas near the shore that are particularly rich in oxygen, filled with sunlight and contain food for all species,’ WWF experts explain.

Intensification of shipping

But if dredging is such a dangerous process, and we are talking about the Danube Delta – a UNESCO biosphere reserve –, are these measures truly necessary? The logic behind these actions is quite simple: all efforts aim to increase the capacities of the Danube port cluster. The deeper the Danube channels, the greater the number of ships with larger cargo capacities that can navigate through them. Given the urgent need for additional logistical solutions for exporting grain from Ukraine, the Danube is becoming one of the most popular routes, and Ukraine is actively utilizing it. Freight turnover in the cluster increased by nearly 600% from 2021 to 2024, indicating a significant rise in ship traffic, which could also negatively impact the condition of the coastlines.

Map showing the Danube Delta.

We visited the Danube Biosphere Reserve located in Ukraine, specifically the areas currently accessible to tourists—the city of Vylkove and Yermakiv Island. While navigating through the Chilia estuary, where cargo ships operate, Tetiana Balatska, an employee of the reserve, drew our attention to the shores.

‘See? The shores were eroded before the speed limit for cargo ships was imposed,’ she says.

Here’s how it works: as ships move through the water, they create waves that strike the shore, gradually destroying it. The larger and heavier the vessel, and the faster it moves, the more pronounced the erosion becomes. Ultimately, this leads to the loss of habitats for species that depend on the areas near the water.

The banks of the Chilia estuary of the Danube. Photo: Victoria Gubareva

The banks of the Chilia estuary of the Danube. Photo: Victoria Gubareva

Evgeny Simonov, a Doctor of Sciences specializing in the conservation of natural systems and the protection of freshwater ecosystems, analyzed photos of the eroded banks

‘This floodplain consists of relatively soft sediments: silt, fine sand, and so on, and it is prone to erosion. This is how flooding develops. When there is a lot of water during floods, new areas are formed through the erosion of the old ones. However, it is one thing when it happens, relatively speaking, once a year or every few years. New floodplains and shoals naturally form, and old banks are washed away. It is quite another matter when erosion is provoked by every subsequent vessel passing through this strait. This results in a completely different frequency of ‘outrages’,’ Simonov concluded. Such frequent and constant destruction, according to him, does not allow the species living near the water to breed, ultimately leading to reduction of biodiversity.

‘It is difficult to say how strong this destruction is. This picture shows that there is a rather strong ‘outrage’, but it is impossible to determine when it occurred. If it is a navigable strait, we can probably say that the erosion resulted from the passage of ships,’ Simonov added. He did not question the fact that the shores had already eroded this year.

According to the scientist, monitoring the impact of the intensification of navigation on rivers requires research in test areas. However, the consequences of further industrialization at the mouth of the Danube can be much worse.

‘My main concern is that this causes further efforts to engineer this estuary. Sooner or later, the [Ukrainian] Minister of Development of Communities and Territories may propose building coastal protection structures. This would have a much more significant negative impact than the collapsing banks. The erosion of the coasts is just the beginning of anthropogenic influence. The subsequent consequences worry me even more,’ Simonov says.

Coastal protection engineering structures can take various forms. For example, in Kyiv, concrete slabs were built on the banks of the Dnipro, specifically on the left bank of the capital. This is the worst possible option, believes Mykola Prychepa from the Institute of Hydrobiology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: ‘Reinforced concrete structures negatively affect water quality, in particular, its self-cleaning abilities, because the shore loses contact with the water. As a result, the plants that grow along the shores cease to function as biofilters. Moreover, when concrete is in contact with water, phytoplankton begins to proliferate, leading to future algal bloom.

This is detrimental to the animals living there, including fish and zooplankton — various crustaceans that feed on this phytoplankton. Additionally, some algae can cause dangerous diseases, worsening sanitary conditions and posing health risks to animals and humans, particularly blue-green algae. Concrete structures along the Dnipro fail to fulfill their intended function. The water, once clear, bloomed. Unfortunately, in areas where people relax with their children and dogs, there is a stench that stretches for quite a distance,’ he comments.

However, there are other methods of shore fortification, and, fortunately, several options exist. One such option involves special concrete structures that are not in direct contact with the shore. Due to their design, they can reduce the impact of waves caused by passing ships.

To reduce the physical impact of the wave on the shore, concrete triangular structures can be placed in a checkerboard pattern in the water, at a certain distance from the shore.

‘When a wave approaches the shore, its force diminishes with each impact on the triangle, reducing the damage to the shore,’ explains Prychepa. Since the concrete triangles do not touch the shore, their sole purpose is to shield the shore from wave action.

This type of structure is used in the Carpathian region of Ukraine, in particular on the Cheremosh River. They help to maintain the shores during floods, and the same principle can be applied to protect the shore from the waves arising from the movement of cargo ships, says Mykola Prychepa. He noted that installing such structures during the period when the birds migrate for winter does not harm the local flora and fauna. Therefore, the only restrictions might be legal limitations on installing these structures within the biosphere reserve. However, since the channel in question is a zone of economic use of the biosphere reserve, such installations should not cause bureaucratic complications. For example, the photo below shows the Cheremosh River, which is also located in a nature conservation area in Ukraine.

PHOTO 04

Historically, earth fortifications were also used to fortify the shores, employing natural materials such as wood and reeds.

‘This method was used in ancient times to prevent the bank from collapsing,’ says Prychepa. ‘Reed bundles were laid in several rows, protecting the shore from erosion, and during large floods, it also helped prevent flooding.’

Another option is planting coastal vegetation, which can serve toreinforce the banks and thus protect them from erosion. For example, reeds can absorb the initial impact of waves, and trees growing on the banks strengthen the soil.

However, a more effective way to protect the shore, especially when it faces continuousimpact, is to lay stones along the shore. This option is better than a solid concrete wall, as we mentioned in the case of the Dnipro, because stones allow for air circulation, and also serve as a home for various species. This option of shore fortification is used on the shores of the artificial Kyiv Reservoir, and quite successfully, according to Prychepa.

‘Stones are a place of shelter, hiding places and even nesting of some birds. Crabs, crayfish and other invertebrates can live there, besides, it is a mechanical protection against the impact of waves,’ says Mykola Prychepa.

PHOTO05

Shore fortification with the help of embankments made of stones. This is a more environmentally friendly way to protect the shores than a solid concrete coating. Photo: Mykola Prychepa

At the same time, the scientist emphasizes that installing any fortifications is stil an intervention in nature. As with the use of concrete triangles, the key limitation in this case is the season in which the fortification work is carried out. Ideally, it should be during the winter months, when the birds have migrated.

What can the intensification of shipping in the Danube Delta lead to?

‘All the water we drink, use for watering plants and in everyday life, we take from the Danube,’ says Tetiana Balatska. She has been living in Vylkovo for several decades. Later, when the heat during our visit forces the team to drink all the water stored for the expedition, Tatiana will simply scoop water from the river into a bottle and drink it. She is sure that it is safe.

‘But we locals are used to this water. I wouldn’t recommend it for you,’ she warns. Shortly before that, in front of our eyes, between the 20th and 25th kilometers in the Chilia estuary, the cargo ship ADELHEID BR under the flag of Barbados was discharging water into the Danube. So is the water in the Danube really safe?

In addition to safety concerns, locals have started noticing other worrying effects of human intervention in the area. Mihai Călin, a navigator who lives in Sulina, a small town on the Romanian side of the Danube Delta, close to Musura Bay, says he’s already seen how the local fauna and flora have been negatively impacted by the deepening of the canal. Dredging works on the Bystre mouth have led to less water flowing into the Sulina and Saint Gheorghe branches of the Danube. This, combined with the drought that ravaged Romania this summer, has led to decreased water levels in the complex system of lakes in the Danube Delta. According to the navigator, the Marghița, Merheiul Mic, Merheiul Mare, Isac, Uzlina, and Roșulețul lakes now hold less water.

A small island on the Sf. Gheorghe Danube canal. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

Lower lake water levels mean less water circulation in the delta, causing vegetation, such as reeds, to effectively ferment. As they decompose, hydrogen sulfide is produced, which is lethal to fish, crabs, and frogs. With no food left, the birds stop coming too.

Călin, who regularly buys fish from local fishermen, has experienced this first hand when trying to consume fish harvested from affected areas. ‘No matter how I cooked it, the fish still tasted like sulfur,’ he complained.

Dan Vasile Dicu, the president of Together for Chilia, photographed next to one of the projects he’s most proud of: the local playground. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

‘We have had fish that tastes like petroleum products’, adds Dan Vasile Dincu from Chilia Veche, a Romanian village close to the Ukrainian city of Chilia. Dincu, who leads the civic group Împreună pentru Chilia (Together for Chilia), believes the altered fish taste is due either to illegal discharges or accidental leaks from cargo ships. He says local fishermen have seen fuel spots in the water, but can’t say for sure whether they’re caused by cargo ships, much less which ones are at fault – leaving them with little legal recourse.

Iulian Nichersu, Scientific Council President and researcher at the Danube Delta National Institute (DDNI) says that the dredging works could be partially responsible for what Călin noticed, but without proper research it’s hard to say how much of the blame lies with the works and how much with climate change.

Water discharge from the cargo ship at the Danube mouth. Photo: Viktoriia Hubareva

Later, we contacted a shipbuilding expert on the Ukrainian side. After looking at the photo, he explained: ‘This is some kind of water discharge. It’s hard to say exactly which type — maybe ballast, maybe from the fire tank, or perhaps from the engine cooling systems. If we assume something illegal, it could even be from the sewage system. But I would bet on the engine cooling system.This involves continuously pumping water through the engine to keep it cool,’ the specialist explained.

Currently, it is impossible to confirm the exact impact of the discharge. However, the discharge of ballast water in this area, although not prohibited by Ukrainian legislation, may harm ecosystems, given the significant intensification of shipping in this area.

Let’s break down why ballast water could pose a problem: Before the advent of steel-hulled ships in the late 19th century, materials like sand, stone, bricks, and even iron were used as ballast, which was relatively harmless. However, with the introduction of seawater as ballast, the story changed. Thousands of tons of seawater taken on board ships often carry local marine organisms, which are then transported to new regions across the oceans. As ship speeds increased, these organisms were more likely to survive the voyage, potentially introducing invasive species to new environments where they had no natural predators.

Each vessel can carry from a few hundred liters to more than 100,000 tons of water ballast, depending on its size and purpose. Water ballast, potentially received and pumped into ballast tanks at or near the port of destination, may contain aquatic organisms at any life stage. Every day around the world, 3,000 species of animals and plants can move in water ballast. The chances of survival for these species after release depend on factors like salinity and temperature in the receiving area. Research indicates that typically less than three percent of released species can acclimatize to new regions, but it only takes one species of predatory fish to cause serious damage to a local ecosystem.

Ballast water poses not only environmental risks but also economic and health threats due to the diversity of marine life it carries, which can include bacteria, microbes, invertebrates, eggs, cysts, and larvae of various species.

It’s not just living organisms that are a concern. The type of ballast tanks on ships varies, and this can also influence environmental risks. There are isolated ballast tanks, which hold seawater in compartments with dedicated pumps and autonomous systems. Then there’s clean ballast, which is stored in tanks previously used for fuel that have been cleaned thoroughly. Lastly, oil-contaminated and oil-containing ballast is highly regulated and may either need special disposal or cannot be pumped out at all due to contamination.

The introduction of alien species into new ecosystems and other pollution from ships’ ballast water has been identified by the Global Environment Facility as one of the four main threats to the world’s oceans. Adopted by IMO in 2004 International Convention on the Control and Management of Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM 2004) is the most important treaty aimed at preventing the movement of alien species with ballast water. According to the rules of this Convention, a ship built before 2009 (and ADELHEID BR is just such a ship, since was built in 2007) must carry out ballast water exchange at a distance of at least 200 nautical miles from the nearest shore and in places with a water depth of at least 200 meters. Also, isolated ballast water can be discharged in the same place where it was collected. Barbados, whose flag flies the ship ADELHEID BR, is a party to the Convention; however, Ukraine and Romania have not yet ratified it.

Instead, in Ukraine in accordance with clause 5-1 Rules for the protection of internal sea waters and the territorial sea of Ukraine against pollution and clogging, the discharge of isolated ballast in the territorial sea, inland waterways of Ukraine is allowed without restrictions and control by state authorities, provided that such ballast was accepted in the Black Sea or the Sea of Azov before entering the territorial waters. At the same time, the State Inspectorate has the right to conduct an inspection under certain circumstances. However, there are so many exceptions, limitations, and conditions for the control body that there have been precedents when, even with visible signs of ballast water pollution, logistics companies avoided responsibility.

Viktor Komoria, acting Director of the Ukrainian Scientific Center for Marine Ecology, explains why the rule of the Convention is not spread in Ukraine: ‘200 miles is approximately 350-400 kilometers. And we have 500 km to Istanbul. That is, it is clear that even in the middle of the Black Sea there will not be a distance of 200 miles to the shores of the countries. But the problem of ballast discharges is a global problem that has not yet found an adequate solution.’

And although we cannot be certain whether the ship poured ballast into the water, or whether it was the engine cooling system on ADELHEID BR, it is possible to claim that ships can pour ballast into the Danube, because there are several ports upstream of the river — Reni, Kiliia and Izmail.

‘One-time discharge is unlikely to cause harm, but if a large number of vessels do it on a permanent basis, which can be called chronic, it can lead to negative consequences. Especially if it happens at the mouth of the Danube,’ comments Komorin. At the same time, he calls it a hypothesis, and, like other experts we contacted, emphasizes: under conditions of strong intensification of shipping, it is necessary to conduct appropriate analyzes and monitor the situation.

Plastic pollution and citizen response

The cargo ships don’t just discharge water ballast, but also proper waste. ‘It was night and I was out on the Chilia branch, when I saw a big cargo ship dumping large garbage bags into the water,’ said a local man on the Romanian side of the Delta. He tried to film the whole thing, but didn’t manage to.

Nature and plastic waste next to Chilia Veche. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

Though video evidence of ships dumping waste into the delta or the Danube is rare, the visible reality is that there is far more garbage in the area since the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine and the intensification of naval traffic.

Sulina always had a problem with the waste, but after the war they started to see more ‘international waste’. ‘Many ship crews threw waste into the Danube and it ended up on our beach. I mean, according to the labels, it was very clear that it was waste from other countries’, says Roxana Saraev of With love from Sulina, a local civic association. This ‘international waste’ consists of plastic bottles and other objects that are clearly brought from abroad. She and her organization regularly organize river bank cleanups. During a single session they collect over a ton of waste, according to Saraev.

The organization, founded in 2022, largely works on environmental issues. ‘Our utopic plan is to make the town completely green’, the woman explains.

PHOTO 10

Trash collected by the locals in Sulina. Photo by Roxana Saraev

Dealing with plastic pollution is a good place to start on that plan, since, according to recent research, it impacts rivers even more than previously believed. One study shows that plastic pollution leads to a significant drop in river water oxygen concentration levels, which affects the natural cycles of the biosphere. This is caused by plastic leachate fostering bacterial growth, which, in turn, stimulates the appearance of parasites.

So, how did we get here, and what can we do about it?

According to the Romanian Naval Authority, naval traffic on the Romanian side of the Danube Delta has doubled since the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine. Around 1700 ships transited the area in 2022 and 2023, compared to just around 850 in 2021 and 2020.

‘Before the war, seeing a cargo ship was an event. Now it’s a common occurrence,’ says Dan Vasile Dicu, president of Together for Chilia, a local civic association in Chilia Veche, a small commune on the Romanian side of the delta. Standing on the river bank and discussing the changes brought on by the war in Ukraine, we looked across the water to Chilia, the village’s Ukrainian sister city. Dicu has lived here for more than 20 years and, at his day job, he’s an officer with the local branch of the Tulcea Penitentiary.

The community, he says, has always faced many problems, mostly caused by its remoteness. Very limited job opportunities, no 24 hours medical assistance, not enough boats to connect it to the mainland and a road in such bad shape that you’re either forced to drive incredibly slowly or risk busting up your car. Fed up with the state of things, in 2020, together with other locals, Dicu founded Together for Chilia, a local civic association, which has since built a playground for kids and pressured the local authorities to address community issues. But then the war started in the country just across the Danube, and it came with its own set of problems. Now, together with Mai Mult Verde, an established national environmental NGO, the local group is monitoring war-related problems and the increased naval traffic on the Danube, under a program called Alertă pe Chilia (Alert in Chilia).

Among the new issues Chilia is facing, Dicu lists large ships sometimes destroying fishermen’s nets, forcing the fishermen to buy new ones. At other times the large cargo ships have destroyed pontoons on the river – most notably and gravely, the Navrom Pontoon, where the main boat the locals use for transportation docks.

The Alert in Chilia program, started in June 2024, aims to identify and monitor areas where trash either exists or is at risk of accumulating, as well as to document waste and notify the authorities. The locals hope to raise awareness on this issue and organize cleanups whenever possible. Local citizens, tourists, and fishermen are all encouraged to take part in the cleaning effort, via word of mouth and facebook posts.

Dicu says the findings range from ‘international waste’, generic trash, destroyed shipping decks or fishing tools. Not all of this is caused by the cargo ships. Fishermen that come to the area during fishing season also sometimes leave garbage behind. ‘They’re not locals, but not quite tourists either, because they don’t stay in hotels or inns, or eat at the local restaurants.’

Cargo ship unloading waste water at the mouth of the Danube. Photo: Viktoriia Hubareva

Among the spots at risk for accumulating waste identified by the team at Together for Chilia is the village’s new mini boat harbor. The water level in the harbor is lower, there’s almost no water circulation and it’s a highly transited area. Without regular cleaning sessions, it can easily turn into a waste dump. On location, we saw a bunch of plastic bottles and lots of vegetation. ‘We don’t know if this trash was thrown here by someone, or if the Danube brought it from upstream,’ Dicu explained.

At the end of the fishing season, in the fall, Together for Chilia plans to run two cleanups, in order to collect the waste identified through monitoring the area.

A plastic bottle in the Chilia Veche harbor. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

An unexpected benefit of their program was that it provided an opportunity to uncover other illegal activities in the area. ‘We found a sign blocking the access to a forest road, asked the authorities about it, and discovered it was illegal.’ They then sent the story to the press, adding extra pressure to restore free circulation. ‘I say it was a good thing, even if it was not what the project was designed to do – because this was an obstruction of the citizens’ right to free movement.’

In terms of managing plastic waste, Dicu is considering installing a barrier on the water to stop waste circulation. Even better, a smaller boat that could collect the rubbish on its own, like this prototype tested a few years ago by the Romanian Environment Ministry. Another solution would be to organize cleaning competitions for boats, like they do in Hungary, where sailing contestants on the Tisza lake collect trash.

‘People in Chilia are not the most receptive to the idea of volunteering,’ Dicu says, when asked about some of the problems he has encountered with the cleanups and other projects of his NGO. ‘We try to tell them: it’s in our best interest, first and foremost, to keep what we have nice and clean. Some agree and come to help, but when your population is poor, aging and disillusioned, words alone won’t get people out of their houses.’ There are now 20 fee-paying members in the association and other 148 associated members, who volunteer and support them. There are less than 2,000 inhabitants in total in Chilia Veche.

Alert in Chilia is part of a series of plans and projects for the community, through which they hope to increase its level of trust over the years. Until then, Dicu still has an efficient strategy against apathy up his sleeve: get the kids first. ‘Kids are happy to help. Then they go home and talk to their parents about it and then the parents become interested.’ They partnered in a local biking competition to get the kids interested in their activities and built a small playground next to which the children in the community helped plant trees. ‘Now, each child knows which tree is theirs and they water and take care of it.’ These kinds of events and activities help children develop a better understanding of nature and the importance of keeping it clean, says Dicu.

He believes that the organization’s capacity for success is informed by his past as a union member, as well as by recent classes and workshops that he and his colleagues have attended. There, they learned how to better document what they see, to communicate with the media, to write complaints to the authorities and to fundraise. All of this is important, because it helps them work better on their mission: improving people’s lives and protecting nature.

They apply for funding both from bigger NGOs, as well as from the local administration. Even under the former mayor, with whom the organization was in conflict, they still managed to put projects together. Yet members say it’s far better and easier, now that there’s a good relationship between the two parties and they can count on the support of town hall.

‘What they do is important, it keeps the authorities on their toes,’ says Timur Ciauș, the current mayor of Chilia Veche.

A garbage bag discovered while monitoring the area as part of the Alert in Chilia program. Photo from Dan Vasile Dicu.

‘But, at the end of the day, it’s all in the authorities’ hands,’ the mayor adds. Other than complaining to the authorities about what they see, there is little else the association can do. ‘We can’t stop or fine the cargo ships,’ says Dicu. This is complicated even for the authorities. When a citizen sees a ship dumping waste in the water, they can call the Romanian Naval Authority. Together with the Border Police, they are the only two institutions allowed to board a foreign ship. The legal process is complicated, so, most of the time, by the time the bureaucratic red tape has been taken care of, the ships have already sailed out of Romanian waters.

‘This situation should be better regulated,’ agrees Bogdan Bulete, governor of the Romanian Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve. ‘Representatives of the Administration of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve [ARBDD, the institution that manages the Danube Delta] or the Environmental Protection Agency should be allowed to go on board.’

‘All we can do is take pictures,’ Dicu concedes when asked about other limitations of the monitoring program. The association does not have the proper training or money to run a true case study of the impact of the war in Ukraine and redirected naval traffic on the Danube Delta. Together with the locals, they do document the Chilia area, but don’t have the capacity to cover the entire region and uncover effects less visible than plastic waste or destroyed docks.

‘It’s not a proper study or monitoring program; it’s just people taking photos. We can’t take proper action just based on photos,’ says the governor of the Romanian Danube Delta.

The Romanian Environment Ministry announced it is planning to conduct a study of the impact of the war on the Danube Delta, but as of publication, the study has yet to start. Public procurement procedures for the study have been announced, but no offer was submitted by the first registration deadline of August 19, 2024. Ministry representatives claim that the purchase will be resumed.

‘It’s a complicated study that needs to take a lot of factors into account,’ Bulete explains. According to him, the ministry is planning a second round of public procurement. Should it come up empty-handed again, they will consider proposing a new set of requirements.

The lack of offers, explains Nichersu, researcher at INCDDD, is caused by the complexity of the study that requires a large staff and previous data that does not exist.

Large cargo ship close to Chilia Veche. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

Another factor to be considered here is the air pollution caused by the increase in cargo ship numbers. Studies show that, in areas with increased naval traffic, the ships are an important source of pollution, which, in some cases, surpass cars in this respect. Since there are very few monitoring stations in Tulcea County, the exact levels of pollution are hard to monitor at the moment. Yet the effect is surely present, says Costel Popa, president of the Center for Durable Policies Ecopolis, an environmental NGO that conducted a study on waste management in the Danube Delta this year.

Aside from air pollution caused by traffic, Danube Delta National Institute researcher Nichersu explains that the air in the area is also polluted by war explosions. Any major explosion leaves a significant quantity of pollutants in the air. The research undertaken thus far supports his claim. ‘These pollutants are then carried by currents for long distances,’ says the researcher. And some explosions aren’t even taking place that far away from the Danube Delta. In September 2023 for instance, the Ukrainian city of Chilia, which is no more than 6 kilometers away from Romanian Chilia, was attacked by the Russians. The researcher explains that, in such situations, some of the polluting particles settle on land and water. The water then travels, taking them even further away.

‘The role of the filter is very important. The reeds act as a filter for the Black Sea. This is why it’s important that ecological restoration continues in the Delta,’ Nichersu explains.

The ecological restoration he’s referring to is part of a series of measures and projects that aim to protect or rebuild the natural habitat of the Delta, mostly to counter the effects of invasive, man-made interventions. These programs are also meant to restore the area’s biodiversity, including reeds, a staple of the Delta, and thus contribute to cleaner water and soil.

We visited such a project near the city of Tulcea, in Mahmudia, where, from 2012 to 2016, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in partnership with ARBDD and the local administration carried out the ecological reconstruction of land in the Carasuhat polder. This piece of land represented 2.3% of all agricultural land in the Danube Delta.

Remains of the old dam at Mahmudia. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

We visited the area with Dragoș Balea, coordinator of the WWF Delta program. As we sailed down the river, we saw pelicans, egrets, herons, and swans. We passed by two adult swans followed by their many offspring. ‘Those two seem like good parents, not always do all seven baby birds survive,’ Balea said.

Before 2016 this entire area was covered by cow pastures. It was part of the land transformed by the communist administration into farmland, in order to increase the country’s agricultural capacity. In the 2000s the land was owned by the local council of Mahmudia, which rented it to farmers. ‘The local authorities wanted the land restored and so did we,’ says Balea, when asked how the project started.

There are now at least 77 bird species in the Mahmudia area. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

After a series of legal procedures and farmer compensation, by 2016 the artificial dam that had held the water back was destroyed, and the area was flooded. WWF planted endemic Danube Delta flora of high ecological value: white poplar, willow, and ash trees. The area is now one of the most biodiverse in the Delta, and the community in Mahmudia has also grown.

According to a study conducted at the request of the WWF, 97% of the people in the community are in favor of the restoration. This is because, Balea explains, tourism has flourished in the area, which created more job opportunities than large scale agriculture. ‘The Delta has a lot to offer. And the communities that live here should prosper,’ he adds.

While Balea thinks this solution could work for other areas of the Delta that are still used as farmland, he does acknowledge that the process can only unfurl with the approval of local authorities – who can be reluctant to such plans.

‘Because these are complex systems: conducting feasibility studies and obtaining permits and approvals is a very long process,’ Nichersu adds.

This lengthy process never truly ends. The nature of the Delta is ever changing, says Balea. Any work done in such an area requires monitoring and upkeep.

‘It’s dynamic and the environment system doesn’t wait for anyone,’ Nichersu says. The Babina polder, for example, which was ecologically restored and reconnected to the Danube in 1994, is now gradually turning into a land area. This, the scientist explains, is natural, but it proves that further measures are necessary, if we want to keep Babina a wetland. For such a solution to work, it needs not just material resources, but also good management and political will. Not just for today, but also in 30 years from now – and beyond. ‘The delta is like a human organism. We do an intervention, but it is not definitive, it must be maintained. ‘

The ecologic reconstruction created at least 18 natural habitats on the former farmland in Mahmudia. Photo: Ioana Cîrlig

Even if such projects are complicated, Nichersu does believe they are a promising possible solution. ‘An ecological restoration of high impact areas is necessary. It’s also necessary to monitor water and soil quality, because scars on the environment have long lasting effects.’

And the scars inflicted by Russia’s war in Ukraine only compound the high stress caused by climate change to the environment. ‘The biggest impact that the war has had is deepening the climate crisis,’ the expert underlines. This has taken on various shapes and forms: increased carbon emissions, pausing or delaying projects necessary for the area’s wellbeing, but also diverting attention and resources away from the existential threat of climate change to the immediate crisis of war. In the future, we are sure to experience more extreme weather phenomena, like the recent and deadly European floods, which have shown us, once again, that the Danube is a force to be reckoned with and that nature doesn’t wait for anybody.

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.