On political speech and the paradoxes of critique after Trump and Gaza; why the far right fills the gap left by restorationist liberalism; and how fascization depends on white middle-class solidarity.

Celebrating the start of LGBTQIA+ Pride 2022: in Brazil trans activists rearticulate language and identity, taking the political campaign trail to greater visibility, recognition and a sense of belonging, helping save lives through collective action and knowing disobedience.

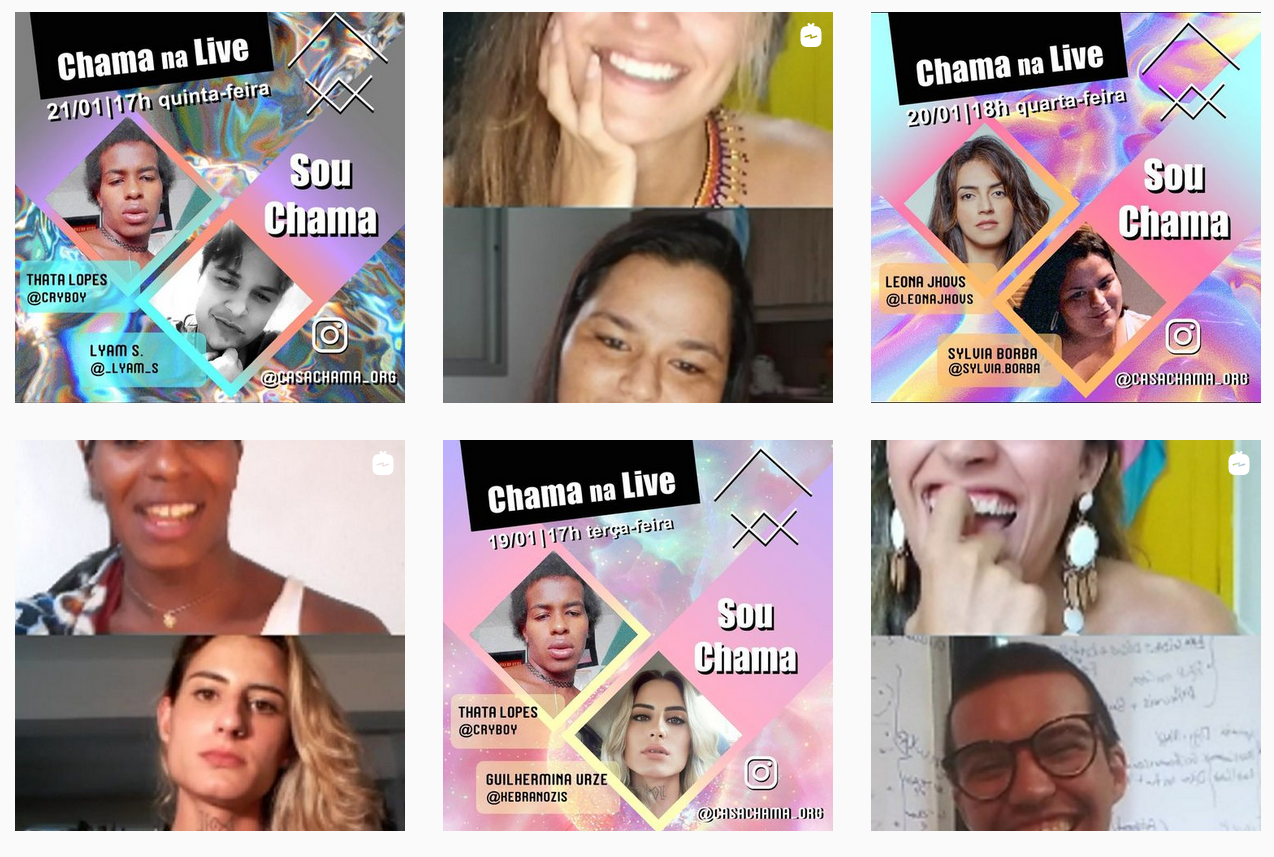

Casa Chama members, image courtesy of author.

Despite São Paulo’s incredibly multi-dimensional cultural life with growing social acceptance and LGBTQIA+ visibility, including the largest Pride parade in the world, violence against trans bodies is still rife in Brazil. According to a recent report, the country has the world’s highest rates of femicide and homophobic/transphobic crimes in the world: of all reported deaths of trans persons in 2021, 82% resulted from violent murder. Even though these staggering murder rates date from long before Bolsonaro, it was not until after his rise to power in late 2018 that 10% of all transphobic murders have been attributed to political motivations.2

Most Brazilian trans women are destined for a life of homelessness and sex work – 90% live in these conditions. São Paulo has the highest number of homeless and poor trans people compared to other large cities in Brazil. Life expectancy among the trans population is only 35 years old.3

These numbers evidence that Brazil upholds an institutionalized trans necropolitics, targeting the systematic precarization and elimination of trans identities.4 Trans bodies are often portrayed as deviant in mainstream media, which further dehumanizes them as ‘not grievable’.5 But what is less known is how self-organized trans organizations are addressing the urgent need for civil rights and protection.

Casa Chama, established in São Paulo in 2018, is a cultural platform and shelter managed by and for transvestigender persons. It is one of several grassroots organizations that mobilized during the 2018 presidential elections against Bolsonaro, realizing the need to protect as many transvestigender lives as possible. In quickly becoming a formal NGO, it could focus on both increasing trans representation and intervening in the ‘cistem’, to attain what Digg Franco, a trans-masculine cultural producer, founder and president of Casa Chama, calls ‘a dignified life’.

Besides working with transvestigender artists, Casa Chama mobilizes allied professionals to provide health and legal assistance, creates employment autonomy programmes, works with damage reduction, strengthens trans governance together with trans politicians, fights administrative violence6 and campaigns for constitutional civil rights.

I have been a Casa Chama ally and collaborator since its inception, when I interviewed Franco for an article documenting pre-electoral, oppositional artistic mobilizations in Brazil.7 We defined Casa Chama as an ‘autonomous zone of [trans] rexistance’8 (from the Portuguese rexistência, a mixture of ‘resistance’ and ‘re-existence’), suggesting that resistance for trans communities is not only an act of opposition to the cistem but also a means to affirm trans existence and humanity.

Casa Chama began as an artistic residency programme, questioning the terms of belonging and the marginalization of transvestigender artists within the art world itself. As Brazilian non-binary performer and essayist Jota Mombaça writes, ‘systems of art (which are part of white and cis structures) are not separate from the social mechanisms that reproduce the critical situation of people who are gender disobedient and Black and racialized sexual dissidents. On the contrary, these systems occupy a privileged position from which what is thinkable and imaginable is determined.’9

Casa Chama neon, image courtesy of author.

Art systems, in this case, are symptomatic of social structures and institutions which are part of the problem rather than the solution. Transvestigender artists require the means to define their visibility and exposure on their own terms. As Cinthia Marcelle, a Brazilian contemporary artist and co-founder of Casa Chama explains, ‘if society does not recognize [trans] bodies as legitimate, [trans] bodies are able to recognize each other through art; and it’s important to consider how big this space can be’.

In the context of art theory, Casa Chama reflects the ‘social turn’, a socially engaged artistic practice embedded in broader social justice movements, as theorized by Claire Bishop in 2006.10 Socially engaged art, generated together and dealing with large societal struggles or discursive and relational practices in line with institutional critique, follows clear participatory and community-based strategies. Casa Chama uses art as a permanent survival mechanism rather than as a temporary ‘helping hand’ for a community to achieve its social and political goals. It presents a critique of established art systems that believe they can mitigate inequalities by simply filling representation gaps but don’t change deeper structures of inequality.

Casa Chama doesn’t act defensively or play on victimization. Rather it follows a clear vision of a future and a system that can be fully inhabited by trans persons, their history and memory, based on notions of collaboration and mutual protection.

The NGO proposes a new way of participating and perceiving social movements. In setting the terms for mobilization and leading by example through its own system of trans governance, self-sustainability and a resignification of (artistic) existence/resistance, it aims for a more epistemic transformation of visibility and participation in the arts. Franco believes that Casa Chama’s philosophy of artistic trans care for a new system is necessary: existing systems either reproduce hegemonic and colonial cis-structures for trans persons or don’t exist.

Speaking of turns – given the past decade of so many (the ‘social turn’, the ‘educational turn’, a global ‘queer turn’) – the ‘cuir/trans turn’ in Brazil and Latin America represents a more radical disruption. As Mombaça suggests: ‘Since the 1960s, the disruptive emergence of anti-racist, queer/cuir, feminist and decolonial discourses and practices has definitively changed the representational horizon which define the politics of visibility.’11

In Latin America, the shift of the term ‘queer’ to ‘cuir’ is radical criticism from sexual, economic, racial, gender and functionally diverse peripheries, all fundamental enclaves for developing a politics of intersectional resistance.

The latinized, tongue-twisted term ‘cuir’ helps to carve out a new locus of enunciation with a decolonial inflection and geopolitical displacement. It counterattacks colonial epistemologies, including Anglo-American (queer) historiography, where Latin American narratives tend to be overlooked, partly because these discursive mobilizations are more recent, and partly because there is a bias in knowledge production that makes peripheral trans narratives less visible and less ‘speechable’ in global contexts.

‘Cuir’ makes visible strategic uses of knowing disobedience, re-imagining life through organized, social insubordination. This in turn helps debase societal assumptions about a ‘disobedient redistribution of gender’ and multiple ‘sexual dissidences’, to use Mombaça’s words, calling for substantial systemic change.

Confronting (trans)necropolitics is therefore about more than trans identity, representation and difference – it is about redefining the basis of humanity. It is about recognizing how each body elaborates and believes in its own capacity for self-defense and self-care, which includes a radical shift in perception. According to Mombaça, learning to defend oneself requires other ways of perceiving one’s own fragility, with strategies and tools which ‘only a body and a subjectivity capable of inhabiting fragility can develop. Self-defense is learning about one’s own limits and developing escape tactics when necessary, as well as learning to read the choreographies of violence and studying forms to intervene in them.’12

As Franco adds: ‘Casa Chama resignifies artistic practice as a political practice of survival, beyond the politics of identity and representation of expanded feminist discourses – we can only be artistic when what we are and how we act is based on freedom and courage, which can only be attained through an artistic outlook on the extreme conditions in which we are living.’

Casa Chama also practices trans care in the way it is organized. Dignity, empowerment and affirmation of resistance enable each person to assume an affective and ethical responsibility in relation to one another. As co-founder Ana Matheus Abadde describes, Casa Chama is ‘detached from a patriarchal, paternalist structure where someone is doing something for you’. It’s a space ‘where we do things with and for each other’.

It follows an ‘open family’ culture built on mutual care, expressed in the motto quem acolhe é acolhido, quem é acolhido acolhe (those who care are cared for, those who are cared for give care). One of the most sensitive aspects of trans life is early-age family abandonment. Therefore, the closeness and trust created in the house is perhaps one of its most important features – to create a place of belonging.

The organization does not refer to the trans community as ‘clients’, nor does it position its support structures as ‘services’, as in typical NGO discourse. It resists the neo-liberal thrust in government welfare programmes, which seek to make basic rights more ‘effective’ from a business standpoint. It refutes the commercialism of welfare, brought about by the privatization of the public sector, and equally opposes top-down ‘charity models’ common in the non-profit sector.13

Casa Chama shares common features with mutual aid projects recently theorized by Dean Spade14: typically organized bottom-up and non-hierarchical, supportive of participatory processes, and having shared leadership and consensus-based decision-making. Within this framework organizations cultivate justice and liberation in all aspects of community life, not just as a single cause.15 As Franco says: ‘Being trans permeates all of Casa Chama organizational processes, from the elaboration of project proposals to their execution and results. Internally, we aim to be horizontal in all aspects. Hierarchies are dissolved in favour of equal voices.’

Decision-making is consensus-based and held in open meetings, where all members can attend. Academic qualifications are not necessary to be hired into the organization. Hiring criteria focus on the level of engagement and understanding of demands from transvestigender experiences and perspectives. On an operational level, all projects and actions are carried out with trans teams that harness the knowledge and skills of its members and help build competencies within the community.

A trans perspective includes identifying and fighting against what co-founder, actress, writer and presenter Leona Jhovs calls ‘everyday transphobia’ when choosing project collaborators, donors and funders. Organizations led by cisgender persons, even within LGBTQIA+ movements, may sometimes disregard deeper aspects that are important to transvestigender persons. Finding funds is a constant struggle, managing new support requests from trans persons requires much affective labour, and promoting action is intense.

The organization’s vision is also to create structures for coalitional work on broader social issues affecting trans lives through a wide range of sister organizations, partners, donors and pro bono professional allies. These are needed to transcend existing systems to achieve self-determination and wellbeing to survive and thrive – dissolving the limits of what is ‘thinkable and imaginable’, as Mombaça suggested earlier, from a place of urgent survival.

Trans flag, image courtesy of author.

Because the trans community is so complex and diverse, Casa Chama can be seen as facing the multiple dimensions of a transvestigender social ecology. Strengthening existing discourses and building networks helps support groups within the trans community that require greater visibility and care such as trans men, for example, whose narratives and needs often go unnoticed in broader trans and feminist discourses.

Growing from an artist collective/residency to an organization that assists 400 people on a regular basis (including but not restricted to artists) and up to 800 individuals needing urgent action during the pandemic alone has resulted in constant internal practice readjustments. What started as a horizontal structure with several co-founders having overlapping functions has developed into more efficient division of tasks and more defined leadership roles. As projects become more robust, new competencies need to be built. Casa Chama needs to reinvent itself to stay afloat, fight exhaustion and remain motivated, requiring patience, encouragement and empowerment.

And yet these adversities also present opportunities for strengthening the overall vision to radically redistribute care and wellbeing, resist co-optation, oppose saviourism, be vigilant if there are any strings attached to donors and funders, keep connected to the root cause and become more sustainable in the long-term.16 As Franco states, ‘if we succeed in creating a robust support structure, including communications and art, for the transvestigender population, our model can be certainly applied to other vulnerable groups in society to achieve change at a systemic level.’

As an autonomous zone of trans rexistance promoting a dignified life, communication is more than of instrumental value or part of organizational strategy at Casa Chama – it is a form of survival itself. With a cast of talented transvestigender artists and performers under its wing, Casa Chama has become a vibrant media production house developing its own media content and cultural events.

Leona Jhovs and other Casa Chama members host weekly live streams on Instagram with guests invited from the organization’s allied professional network or the wider trans community, including politicians, professionals, academics and celebrities. Even though this format was used before COVID-19, it became increasingly popular in Brazil during the pandemic, enabling discourse, contact and presence during lockdown periods. The initiative went beyond merely curbing isolation to develop a deeper ‘voice of care’.

The live sessions cover a wide range of themes from trans childhoods, safe sex, ageing as a trans person (especially in a population with such a low survival rate), hormone transition and human rights to art and much more. The archive of these sessions, interspersed with a variety of other content such as candid photos, info on crowdfunding campaigns, announcements and activistic memes, is a record of a significant media activistic strategy.

As a living archive, it contributes to the broadening of what one might call the online musealization of trans experiences, which fills a gap of marginalization, invisibility and erasure of trans voices in mainstream culture, including art institutions. It expands the conditions of possibility for dissident ‘cuir’ narratives under which trans lives are recognized. More importantly, considering the thousands of trans lives cut short at an early age, this archive is also urgent – it acts as an enabler of trans memory with a history that remembers trans lives, making them therefore grievable.

If we examine the dialogic conversation format of a live session more closely, where two people share the same screen in conversation, we can see social media as a form of trans care when approached as a space for historicizing and promoting respect for human rights and trans diversity. This rather intimate format makes transvestigender bodies and subjectivities ‘speechable’ beyond one-way broadcasting communication or mute art displays in a museum.

It also demystifies Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s notion of the disposable, speechless, subaltern trans body usually framed in media as the invisible other, into one that actively speaks and produces knowledge and discourses on its own terms.17 As the AfroPortuguese artist and writer Grada Kilomba reminds us, one can only ‘speak when one’s voice is listened to. Within this dialect, those who are listened to are those who “belong”’.18

But this medium also presents a paradox of visibility. Even if the ‘voice of trans care’ and its visual manifestations promote a radical discourse of love and acceptance, themes like hate speech and cyber-bullying often resurface in live conversations. When Jhovs asked Black-Amerindian trans activist and art director Neon Cunha about this paradox of visibility, of being attacked because of this new way of making trans lives visible online, she said:

People are bound to attack us on the Internet. In order to achieve humanization online, we need to state firmly that our bodies are constantly being dehumanized. Our struggles are somehow directed towards non-trans people, who insist on keeping us in a vulnerable place, even though we try to occupy more spaces with our discourses. On the other hand, we have gone a long way, there is more dignified visibility, there have been openings where we can practice our trans existence. We are now in a possible place, by us and for us.19

Casa Chama indeed experienced relatively little hate speech or cyberbullying until a phishing attack in early December 2020, which suspended the account temporarily. Community Manager Lyam S. quickly responded with a social media message: ‘No transphobic crime will be able to silence us … Our voices are built in a network, as Jota Mombaça says, “they will not kill us just yet”. … THEY WILL NOT SILENCE US!’20

Casa Chama artists, singers, actors and performers are part of a larger movement of transvestigender celebrities who have been breaking new ground in the cultural scene since the early 2010s. Names like Liniker and Linn da Quebrada are examples of trans women who have inspired a new generation of transvestigender musicians and performers to overcome histories of poverty and precarity by stepping into the limelight of contemporary culture.

In 2019 Casa Chama organized its first festival uniting trans discourses, politics, cutting-edge artists and representatives of trans movements to a large audience in São Paulo. The ambition was to unite a network of trans mobilizations nationally and internationally on a unique cultural and political platform which did not previously exist.

The second Chama Festival – TRANSversalities held in May 2021 – marked the return of transvestigender artists who had been away from the stage, cameras and studios during the pandemic, and promised to showcase, according to Franco, ‘the changes we have been living through in shows that conjoin stage, scenery, colours, voices, memories and journeys in a creative way’. As in all of Casa Chama’s initiatives trans protagonism appeared onstage and backstage.

The festival – performed in politically radical Teatro Oficina, as in the first incarnation, but streamed online for four consecutive nights – included a careful choreography of music, slam poetry, experimental dance, performances and speeches, intertwined with a more discursive programme of Casa Chama activities. These included backstage talks, artist introductions and panel sessions touching on urgent issues faced by the transvestigender community during the pandemic year, transforming the festival into a powerful political platform.

For those who were familiar with the struggles, the festival felt like being at home. For those new to the discourse, it was a learning opportunity to engage with transvestigender issues through Casa Chama’s and trans communities’ voice of care.

‘Transvestites will heal this nation’, image courtesy of author.

One month later, a similar digital format was used for the first festival dedicated exclusively to trans-masculinities, agenders and non-binaries, Chama em Ação (Chama in Action). Among the individual contributors was voice actor and trans-masculine artivist Gabriel Lodi, who appeared as a festival host and for whom acting is ‘a way to get out of invisibility and create a possible existence for others, to normalize our trans existences and “corpas” so that we can exist’ … ‘I turn the stage, the camera and voice dubbing into an experience that naturalizes trans bodies, both as a celebration of our resistance and as a strategy for hacking spaces’.

Lodi refers to the act of trans bodies occupying new spaces to recode them into opportunities for finding community and challenge the status quo. Hacking as an act of disobedient space-making is integral to efforts at defying injustices, ‘everyday transphobias’, and reprogramme what is ‘thinkable and imaginable’.

The ‘cuir/trans turn’ in Casa Chama’s communication strategies and artistic production results in the possibility of a new trans politics of visibility, memory and political action for transforming the world from a dissident perspective. Social media platforms become extensions of its politics of trans care and artistic expression with living archives pulsating with the potentiality of writing new histories that transcend trans necropolitics by prolonging and dignifying transvestigender communities.

What has become more evident since the pandemic is that social media provides places of memory, refuge, visibility and mobilization for movements of resistance and social justice, which expand current repertoires of practices of solidarity and radical emancipatory politics. One can only hope that this type of approach to life, dignity and humanization of transvestigender lives inspires other organizations doing survival work to reflect on trans theorist Dean Spade’s proposition about how practices of generosity and hospitality in times of crisis ‘can become long-term support systems that we can co-govern to help us all survive and mobilize for change.’21

This includes moving transvestigender politics out of its single-issue isolation to larger discourses about racial and gender justice, police brutality and making experiences more available for coalition-building projects. ‘Our work is always a political process,’ says Franco, ‘in politics we began and in politics we will make the biggest change.’

Despite the trans genocidal conservatism of the Bolsonaro government, there never have been so many trans politicians in political office in Brazil as there are today. In 2020 more than 270 trans candidates ran for municipal office, able to use their legal names instead of birth names on voting ballots for the first time – representing a huge victory for trans political rights.

Among them, Erika Hilton, a 27-year-old black trans woman from São Paulo and a close ally of Casa Chama, was the most voted trans person in the history of Brazil and the most voted woman in the largest city council in the country in that election. Like most young Black trans women, Hilton survived prostitution and homelessness and eventually earned a degree in gerontology. She later became a digital influencer for human rights which led her into politics.

In one of Hilton’s first speeches at the São Paulo City council plenary session replayed during an interview with Casa Chama, she stated ‘this parliament will have to accept that there will be trans men and transvestites in here, and we will not be intimidated by shallow attacks by lunatic colleagues, we will not stand here to remind elected officials that their role is to work for the entire city. The politics need to be intersectional, wide-ranging and enable dialogue across all sectors.’22

Hilton’s election, supported by Casa Chama, multiple trans communities and more than 50,000 voters, is not the result of the benevolence of the cistem, it is the result of the achievements of social struggles signalling a ‘cuir’ turn in Brazilian politics. As Neon Cunha says in one Chama na Live session: ‘Our existence makes possible the idea of a more plural humanity for everyone. We are experiencing freedom, we inhabit a possibility of being who we are, which can be liberating for everyone’ – to beat back the explosive growth of fascism, dismantle racist and transphobic state violence, and build strength to take action and protect one another.’

Author’s note: Thanks to Digg Franco and Casa Chama for the trust, friendship and integrity.

Chama na Live can be accessed via @casachama_org

Transvestigender is a term used to embrace the different identities of its stakeholders. It was originally coined by Brazilian activist, sex worker and transvestite politician Indianare Siqueira, combining the terms ‘transvestite’ and ‘transexual’, encapsulating the fluidity of masculinity and femininity as non-binary. The term has ‘transgressive power in denouncing the urgent need to reconstruct gendered conceptualizations in practice and in theory, to disrupt the violence caused by binary gendering, and to recognize the power and potentialities of multiple gender identities at a political level’. Puta Observatório Transvestigênere, 2020, https://putaobservatoriotransvestigenere.wordpress.com/

Benevides, B. & Nogueira, S. (eds.), DOSSIÊ ASSASSINATOS E VIOLÊNCIA CONTRA TRAVESTIS E TRANSEXUAIS BRASILEIRAS EM 2020, Associação Brasileira de Travestis e Transexuais, 2020, https://antrabrasil.org/

The Brazilian national average life expectancy is 75 years of age.

Reference to Achille Mbembe’s definition of necropolitics where the lives of those from ‘relevant’ social groups are protected at the expense of those considered social ‘pariahs’ by the state. See: Mbembe, A. and Meintjes, L. ‘Necropolitics’. Public Culture, Volume 15, Number 1, Winter 2003, pp. 11-40.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?. Verso Books, 2016.

See: Spade, D., Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law. New York: South End Press, 2011.

Löfgren, Isabel. ‘Fragments of an Ongoing Nightmare, Written from an Autonomous Zone of Resistance in a State of Perplexity’, Paletten, 2019.

Inspired by Hakim Bey’s theory of ‘temporary autonomous zones’ (1991) According to Bey, ‘a TAZ is a deliberately short-lived (or else precarious) spatial zone in which peak experiences and altered consciousness are realized, in a context of “autonomy” or the absence of hierarchy’.

Mombaça, Jota. Rumo a uma redistribuição desobediente de gênero e anticolonial da violência!, Oficina de Imaginação Política: São Paulo, 2016. The text commissioned by the 2016 São Paulo Biennal, “Incerteza Viva”. (Towards a Disobedient Redistribution of Gender and Anti-Colonial Violence!)

Bishop, Claire. ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents’, Artforum, January 2006.

Mombaça, p. 4

Ibid.

Spade, D., Mutual Aid - Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next), Verso Books, London, 2020.

Ibid, p.28.

Ibid, p.19.

Ibid. see Chapter 4.

Spivak, 2010.

Kilomba, G. Plantation Memories: Episodes in Everyday Racism. Unrast Verlag , 2008, pp. 21-22.

Author’s translation. Neon Cunha, Instagram @casa_chama_org, 2 October 2020.

Author’s translation. Lyam S., 11 December 2020. Casa Chama, 2020. @casachama_org. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/casachama_org/?hl=en

Spade, D., p. 45.

CHAMA TALKS #01 | Erika Hilton, Youtube, 18 February 2021, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZO3gNcF42-k.

Published 1 June 2022

Original in English

First published by Ord&Bild 3/2021 (Swedish translation); Eurozine (shortened English version)

Contributed by Ord&Bild © Isabel Löfgren / Ord&Bild / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

On political speech and the paradoxes of critique after Trump and Gaza; why the far right fills the gap left by restorationist liberalism; and how fascization depends on white middle-class solidarity.

Cultural humanitarian aid risks diminishing the complexity of creative work to ethnic kitsch: well-meaning initiatives rate nationality over content. And when the work does receive critical attention, only art that portrays trauma cuts it. Soon thereafter, Western interest fades. Could answers for meaningfully decolonizing Ukraine lie with other formerly colonized communities?