Recent urban development in Moldova’s capital city Chişinău is in many ways typical of other post-Soviet cities where aggressive privatization and the de-industrialization of urban economies have prompted the rise of social inequality. Sociologist and urban activist Vitalie Sprinceana describes how Chişinău’s citizens and activists are rehabilitating urban space by forging new urban networks and creative communities.

On the one hand, the city of Chişinău has many serious problems: the degradation of remaining public spaces (parks and green areas, sports and cultural infrastructure, recreational areas, courtyards and playgrounds, etc.) due to inaction or weaknesses on the part of the local administration; the mass privatization of public property that transformed many public spaces into commercial, private zones; the explosive growth in the number of cars in a city with an infrastructure clearly not suited to a high volumes of traffic, which has led to many public areas being transformed into informal parking lots; the pernicious manner in which residential housing has been constructed, with new blocks of flats inserted in-between existing ones (densification), resulting in many green areas, playgrounds, sports facilities and other spaces being destroyed in order to make way for the new blocks; the demolition of what remained of the architectural heritage of the old city; the constant exclusion of citizens from decision-making processes related to urban policies, city development, funding, cultural policies etc.

These problems arise from a combination of several factors: accelerated reforms linked to the introduction of the market economy; the de-industrialization of urban economies and the growth of the service sector; the rise of consumption and the gradual dismantling of the socialist welfare state, leading to a rise in social inequality, political and religious populism, and the consolidation of politico-economic oligarchies at both local and national levels.

However, on the other hand, these problems are not the centre of attention in public debates at the local level. On the contrary, some of them are being bluntly ignored while others are constantly attached to unrelated discussions: identity wars, geopolitical talk, administrative populism (making huge promises for the future in order to distract attention away from and ignore current issues). As a result, the topic of the city is not a topic in itself but a “dependent” (and secondary) topic inserted into other political discussions and used for other political purposes.

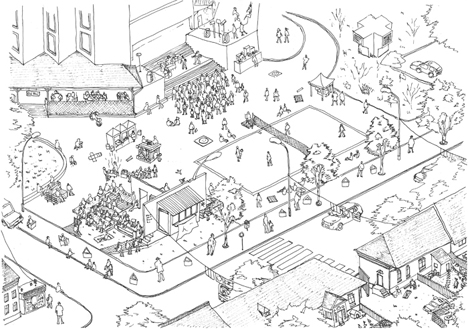

Plans for an urban intervention in Chişinău, realized 20-27 August 2012 by Ştefan Rusu and Oberliht Association; the accompanying workshop was attended by architects, sociologists and artists from the Czech Republic, Georgia, Romania and Moldova. Drawing: George Marinescu, studioBASAR. Source: studioBASAR

This is why a small community of urban activists from Chişinău pursues not only a struggle against the effects of the processes mentioned above, but also, on the discursive and the political levels, it attempts to impose the topic of the city on the public agenda as a trans-party, trans-ethnic and trans-identity issue. In order to do this, the community has to extract urban problems from all the false debates into which they are inserted by the administration and the mainstream media, among others.

This process is also a process of self-reflection and self-recreation, since the activists themselves come from different ethnic, political and linguistic backgrounds (some of them are Russian-speaking, some of them Romanian-speaking) and they first have to negotiate all these differences among themselves.

While there have been discrete cases of urban activism before (protests, petitions), it is only with reference to the last four to five years that we can talk about the emergence of an activistic urban movement that gathers together organizations, informal groups and individuals which collaborate on a regular basis on topics ranging from the preservation of heritage and access to information to ecology and animal protection using various methods – petitions, campaigns, protest actions, etc.

This new urban activistic movement differs from the old forms of activism in that it has not only succeeded in developing and using “reactive action” (i.e. to oppose an action of the state or local authority, of economic agents or of other groups of citizens – such as the demolition of monuments or the operation of illegal construction works). It has also successfully employed “proactive action” (i.e. to suggest and ask for alternative practices, to anticipate some developments and try to pre-empt them; here forms of participatory budgeting, participation in civic society and in decision-making processes, etc. come into play).

Two iconic cases highlight these practices. The first one – the Anti-Sbarro protest – is a case of “reactive action”. The second – the rehabilitation of the Zaikin Square – is a case of “proactive action”.

The Anti-Sbarro protest in Europe Square

Europe Square, situated at the entrance to the “Stefan cel Mare si Sfant” Public Garden, was inaugurated by the Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Moldova and the City Council of Chişinău in 2008. A floral display depicting the EU logo and a newly installed flag marked the occasion. The local administration invests enormously in the symbolic aspect of this location; this is where each year, the mayor presents his annual activity report to the citizens.

At the beginning of December 2012, a fence went up around the square, indicating that construction works could be expected. There was a lack of information concerning the new construction site from the very beginning: the poster on the fence did not show what kind of construction was to be built, who was responsible or when the construction was supposed to be ready.

Later it was revealed that the construction would accommodate a branch of the Sbarro pizza chain. Local authorities stated only that the construction was “perfectly legal”. Several initiatives – Save Green Chişinău Association, Salvgardare Association, Oberliht Association, the Agency for Inspection and Restoration of Monuments, as well as informal groups of other active citizens and bloggers – decided together to demand transparency in the construction process and the organization of public debates as required by law. When city hall did not react in any way, public protests were scheduled for Wednesday 26 December at 11:00 am. In the meantime, the civil society initiatives created a Facebook page and a blog dedicated to the protest.

It was the first time that several groups and initiatives had worked together: they were able to efficiently share the tasks of requesting official documents from city hall, researching legal aspects in order to prepare a legal defence, the printing of banners and slogans for the protest, etc. The protest quickly caught the attention of the mainstream media and went ahead as planned, on 26 December, without any major setbacks. The press, widely present, provided generous coverage of the event and gave voice to the protestors’ statements.

At this moment, Mayor Dorin Chirtoaca ordered construction on the site to stop until its circumstances could be clarified. Thus the first objective of the protest to stop the construction work was successfully accomplished. However, the same evening, under the pretext that the mayor’s order had not yet been presented to them, the entrepreneurs responsible resumed construction and poured the concrete foundation of the future pizzeria.

An activist who witnessed this by chance immediately passed the news on via social networks. Several other activists, accompanied by television reporters, went to the site and filmed the process. Mayor Chirtoaca also appeared, promising to punish the entrepreneurs for wilfully disobeying city hall orders. The next day, the secret construction work was broadcast on television and drew much commentary.

At this point, the mayor ordered the fence to be removed. This was done the same day and the pizzeria foundation was demolished later that spring. From the point of view of mobilization, media presence, pressure on the authorities and the eventual dismantling of the illegal construction site, the Anti-Sbarro protest represents an exemplary story of success. Furthermore, in order to avoid future scandals, city hall began to publish on its official website details of all construction authorizations applied for and of those granted. More broadly speaking, the protest also initiated the practice of opening up access to sensitive subject material regarding historical sites, so that such matters could be debated publicly.

In 2014, another developer, Finpar Invest, a company linked to one of the most powerful oligarchs in the country, Vlad Plahotniuc, announced its intention to build a 15-floor hotel in another corner of the public garden, on the former site of a small cafeteria built during the Soviet era. The activist community reacted again, mobilizing, writing online petitions (which gathered around 4000 signatures), organizing public debates on the topic, monitoring judicial procedures (the company sued the City Council and wanted permission to privatize the site but the court denied their motion).

The rehabilitation of Zaikin Park

In the late 2000s, Oberliht Association set out to implement a project aiming to develop a network of multipurpose public spaces, as an alternative to the public spaces designed under previous political regimes (e.g. Piaţa Marii Adunări Naţionale). The new public spaces, conceived of as an important element of democratic infrastructure and essential for the exercise of human rights and freedoms, were intended as sites for civic and artistic initiatives, and to bring together communities around social rehabilitation and revival projects. In the context of the debate on the radical transformations that public space had been forced to undergo in Chişinău in the wake of the transition, and given the need to protect public space, the community of artists and architects in Chişinău raised the issue of Cantemir Boulevard, which was designed in the 1970s by the Soviets but never realized, and remains on paper. Two decades after Moldova proclaimed its independence from the Soviet Union, the said boulevard exists solely as a project in the General Urban Plan for the city of Chişinău.

In this case, the activist community decided not to wait until the question of the boulevard was solved politically at the level of the City Council but to act pre-emptively. Believing that the only barrier to such megalomaniac urban plans is a vibrant, organized community that could, if necessary, stand and fight against the Cantemir boulevard, several organizations (led by Oberliht Association) initiated an ambitious project of community building in Zaikin Pak, a small green area on the axis of the would-be boulevard. The project has several aims: first, to rehabilitate an area that had been neglected for many years previously. This includes installing urban furniture such as benches, a playground, some sports facilities and adding two new elements – a public water source (there are no free public sources of water in the centre of Chişinău) and a community centre.

Second, to organize and consolidate the community, including via events and workshops. For the coming summer, Oberliht intends to organize, together with a group of architects, a summer school on participative architecture, during which architects and inhabitants of the area will start building the urban furniture for the park. Third, the activist community is pushing the local authorities to be actively involved in these processes, both as a partner (via a civic-public partnership) and a mediator among many actors – inhabitants, developers, civic society, etc.

In a similar way, other groups of activists have initiated other rehabilitation projects for neglected areas (mainly public squares) – the Cekhov Square (a small square situated in front of a theatre), the Decembrists Square, the Rotonda (a complex of stairs and fountains in one of the biggest recreational areas in the city), and so on.

Conclusion

These cases (and several others) clearly show that there is a positive dynamic in the field of urban activism in Chişinău. During the last two years, the community has initiated efforts to consolidate itself in a horizontal, leaderless Urban Civic Network. However, there are many challenges, not least the sustainability of these efforts and making the connection between “urban discussions” and other important discussions in Moldovan society on issues such as poverty, economic and political inequality, and exclusion.

Published 13 May 2016

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by European Cultural Foundation © Vitalie Sprinceana / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- The city belongs to all of us

- No collaborative economy without commons

- Polish culture is turning barren

- Creating the commons in Spain: The current state of play

- Creating the commons in Moldova: The current state of play

- The power to refuse

- Culture WITH people, not just FOR people!

- When commoning strategies travel

- A rough guide to the commons

- New models of governance of culture

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

On making commons concrete

The Dutch Review of Books 2/2021

‘The Dutch Review of Books’ presents: the commons, vying for legitimacy between state and capitalism; the void of societal responsibility for #MeToo; and African oral traditions evident in rap music.

Democratic ‘Third Places’

dérive 10–12/2020

Urbanist magazine ‘dérive’ on emancipating Brazilian museology; the potential for Polish cultural centres; Swiss commons as a transferable prototype; and post-explosion Beirut.