The ‘Bangkok of Europe’

A vicious cycle of destitution locks large numbers of Hungarian women into sex work. Moving to western Europe to avoid prosecution, their vulnerability and isolation only increases. Réka Kinga Papp on systemic exploitation in the European sex trade.

Hungary is a major player in the European sex trade, not only as a host country for sex tourism and domestic punters, but also as a major provider of the labour force that works in western European countries. The scarcer the economic opportunities in a region, the more likely locals are to enter the trade and end up either providing or managing sexual services far from home.

So much so that there are streets in Amsterdam’s red-light district famously known colloquially, among social workers, police and sex workers, as ‘Nyíregyháza’, after the regional centre of an exceptionally depressed region in north-eastern Hungary which, along with its surrounding villages, supplies these same streets with sex providers.

There are other examples throughout the continent where Hungarian citizens – the vast majority women – work in extraordinary numbers, and whose work and travel are managed, and their income skimmed, by other Hungarians. Sometimes this is by agreement, at other times by force or manipulation, or simply because of a lack of alternatives. Journalist Veronika Munk has been reporting for years on an entire street, Lessingstraße in the German port of Bremerhaven, where even the local diner is run by Hungarians, serving sorely missed national dishes to homesick prostitutes and sex workers in their mother tongue. NGOs and social services in Berlin, Zurich and other major cities employ social workers from Hungary and other eastern European countries in order to allow them to communicate with their target audience: often isolated, mistrustful people, who are scared or do not even know how to get health checks or legal aid, and fear to ask for help.

International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers 2010. Source: Flickr

A threat to western morals

The most frequent destinations for Hungarian sex workers are Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the UK and of course, the Netherlands – countries that have legalized prostitution itself, while circumscribing it in various way. A great number of prostitutes are trafficked, promised work that doesn’t involve sex, or offered an arrangement that then turns out to be impossible once they are abroad. Others are luckier and can negotiate the terms on which they work. Yet many do not speak the local language and have no social network in their countries of destination, and so are entirely dependent on their traffickers and procurers.

Eastern women have long been seen, at least in the popular imagination, as having a corrupting influence on western morals and welfare – at least, since the fall of the Iron Curtain and the international mobility of easterners became an everyday reality. It is not only angry Brexiteers who fantasize about cheap Eastern labour destroying their livelihoods. Sweden, for instance, witnessed public outrage against eastern Europeans as early as the second half of the 1990s.1Some even fear for their heroic ‘stag weekenders’: quoting an unnamed charity worker who described Budapest as the ‘Bangkok of Europe’, the British tabloid The Sun discussed in detail the fate of one Englishman – credited with staging ‘the finest stag do in history’ – who was found dead at the bottom of a stairwell in the city with his trousers around his ankles, minus his socks, shoes, phone and wallet. Though no evidence of third-party involvement was discovered, reports of the incident stressed how deeply decadent Budapest supposedly is, warning stag tourists to look out for each other and if possible, avoid the city altogether.

Budapest residents experience significant disturbance from these fun-seekers, from the violence in the streets, the frequent harassment and noise, not to mention urine and vomit liberally dispensed around the so-called ‘party hood’: downtown Budapest’s historical Seventh District. The hardest-hit areas have started to advertise themselves as accepting no stag parties, and an alliance representing them is trying to get travel agencies to alter their promotional materials so as to not emphasize cheap booze and cheap sex as the main attractions.

Because Budapest really is cheap. In 2017, the average salary in Hungary in 2017 was around two-fifths of the EU average: local wages stand no chance in competition with tourists’ purchasing power. Residents have been protesting to their local governments about these issues for almost a decade, yet the profits from hospitality seem to override civic interests. Locals are decreasing in number anyway: cheap flights and the enormous price gap have resulted in a tourist boom that has generated gentrification and priced residents out of the market, which has only worsened the existing housing crisis. Politicians have promised action but have done little.

Ever fewer choices

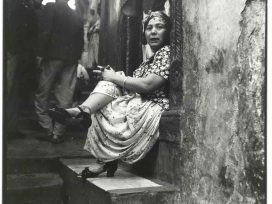

While westerners fear for their morals, Hungarian sex workers and prostitutes seem to have an entirely different experience. It is marked by unemployment; social disadvantage – including racism towards the Roma population in particular; gender inequality in workplaces; housing crises; salaries that don’t cover rents; police harassment; and extreme stigmatization.

The Hungarian Association of Sex Workers (SZEXE) provides legal aid, social work and other services for this vulnerable group. It estimates that roughly 10,000 people work in the Hungarian sex market. According to their 2017 survey, over half of those who responded were raising children. 12.5 per cent stated they were male, so the vast majority identified as female, providing services overwhelmingly for men. Only a tenth of those surveyed worked on the streets, which, despite the inevitable latency of such a survey, does match the experiences and estimations of social workers in the field. This means some 90 per cent work out of sight. Streetwalkers, of course, face the greatest amount of violence and police brutality. Most choose to sell sex from among fewer and fewer options, as they are often heavily discriminated against.

26.3 per cent of the population are at risk of poverty, according to Eurostat; the Hungarian Central Statistical Office has stated that 14.9 per cent, or roughly every seventh person, qualify as poor. Absolute poverty rated 7 per cent in 2014. Even among those with seemingly steady financial background, experts estimate that up to 4 million people may experience housing poverty, in a total population of 9.9 million. The Roma population faces multiple challenges in the labour market.

The Budapest Institute, a think tank, states that 68 per cent of Roma live in income poverty, roughly five times the level among the non-Roma population. A study by the Equal Treatment Authority stated that Roma face ten times more disadvantages in the labour market: employers do not trust them, typically arguing Roma have an attitude problem, and rationalizing any Roma success by pointing to external factors. Roma children are already discriminated against throughout public education, have a harder time advancing in the school system and have even worse prospects when applying for jobs. Many human resources professionals even admit to filtering those with brown skin in the application process.

Women constitute the vast majority of those who sell sex, and this group is also disadvantaged in making a living. Eurostat has reported a 20.1 per cent gender pay gap in Hungary; the average across Europe is 16.4 per cent. The 2008 financial crisis affected women’s employment badly, but losing jobs was not the only factor that has thrown many into the sex trade.

Rents, mortgages, tuition fees

Many sex workers cite ballooning mortgage payments and increasing rents as the main reason for their having to look for a new means of making a living. A huge proportion of Hungarian housing loans were administered in Swiss francs throughout the 2000s, which resulted in exponential growth in repayments when the value of the Hungarian forint collapsed as a result of the financial crisis. SZEXE had middle-aged housewives begging for advice, stating they needed to start selling sex right away as they could no longer afford their mortgages. Others left their public administration positions, as pedagogues, health care professionals and the like, because their salaries did not cover skyrocketing rents. Many students started escorting because the higher education budget cuts resulted in a decline in university scholarships and in the number of state-funded places; also, parents became increasingly unable to finance their children’s college and university expenses.

Escorts, however, constitute a thin layer at the top of the heavily stratified sex market. Some may work for agencies that disguise themselves as either modelling agencies or non-sexual escorting services; they are most likely to specialize in serving domestic businessmen and politicians. Independent escorts who manage themselves find a steadier clientele in travelling foreigners, who will pay the 150 to 180 euro average hourly rate without a second thought, often not even realizing that their ‘date’ is in effect earning almost as much for dining with them as the average local takes home as their monthly salary.

The majority of sex workers serve domestic clienteles, working indoors in apartments, at prices that are around one-third of what escorts make from foreigners. Many work independently but, due to heavy stigmatization and defective legislation, are often blackmailed by neighbours and relatives, and even landlords. Hungarian law forbids renting out property for the purpose of prostitution and obliges owners to end contracts if such activity is found to be taking place on their property. This is a result of the 1951 UN Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others (also known as the ‘New York Convention), which was originally intended to eradicate brothels and the exploitation of prostitutes. In reality, it is hardly ever used in defence of those selling sex, but instead serves as grounds for landlords to blackmail their tenants, and for third parties to threaten to report them. It is only legal to sell sex on one’s own property – but if they owned their own apartments, most sex workers would not choose this means of making a living.

The law also demands that no other person is present at the venue but the punters and sex worker themselves; any third parties – whether selling sex themselves or doing anything else – are deemed as a procurer or accomplice and thus subject to criminal prosecution. This legal solution was intended to protect prostitutes from exploitation, but in practice ends up putting them in danger, as they have nobody to seek help from when faced with violence. The police are most often hostile; sex workers report extreme cases of abuse of power by officers.

Although street workers constitute only a tenth of all those selling sex, they earn the least and face the most abuse and violence. Even though prostitution itself was legalized in Hungary in 1999, municipalities have failed to establish the designated areas prescribed by the law. Local governments have not addressed the matter, in order to avoid conflicts with local residents. Partly as a result, the police find ways to persecute sex workers in any way they can. Extremely high fines are issued for standing in the wrong place, or for other ridiculously petty reasons such as littering or obstructing traffic. Though prostitution itself might be legal, circumscription and misdemeanour regulations allow the authorities to shower prostitutes with fines that often add up to tens of thousands of euros, which the recipients are obviously unable to pay.

This has the desired effect. Unpaid fines become prison terms, which can result in the subjects spending up to two years behind bars. Similarly, hybrid forms of theoretical legalization and penalizing circumscription apply in many countries of the former communist bloc, for instance in Ukraine and Serbia.

Adults are not the only ones affected by this tendency. The child protection law, the law on prostitution and a number of international conventions declare that children can never commit, but are in each and every case, the victim of prostitution. Yet in 2015, the Hungarian authorities persecuted 101 children for charges related to prostitution, leaving thirty of them with fines and nine in detention (since 2013, children have become criminally liable). Eighty-six underage citizens were prosecuted on related charges, eleven of whom had to pay fines and twelve of whom served time in prison.

Police and child protection agencies view the children involved in prostitution as criminals, often blaming them for what they have been through. Children in foster care face extreme hardship and at an early age are already aware that when state institutions let them go, they stand almost no chance in the outside world. A large proportion of them are Roma, but regardless of ethnicity, their chances for quality education are few. One social worker employed in a juvenile detention centre on the outskirts of Budapest was laughed at when she tried to persuade young inmates to avoid selling sex. ‘What should I tell them? Should I lie to them, that they will find a job without education or a social network? They already know what they can expect.’

A vicious cycle of prostitution

Advocacy groups report that a significant number of those who go abroad to sell sex do so in order to avoid domestic prosecution. Those facing prison for not paying fines often leave the country for the two years it takes for misdemeanour sentences to lapse. This puts them in further danger. Some streetwalkers may be able to work independently, avoiding pimps or traffickers at home. But in a foreign country, their capacity to defend themselves and work independently decreases dramatically. Many cannot even arrange for their own travel, let alone find legal places to work, get housing, pay deposits and deal with local gangs.

The renowned Dutch human rights lawyer and expert in human trafficking cases, Marjan Wijers, says her clientele is often scared of asking for help or even of accepting it, although the approach is far friendlier and legally correct than what they are used to at home. Eastern European victims of trafficking tend to mistrust the authorities because of their experience in their home countries. This, says Wijers, is increasingly the case with people who have been involved in the sex trade at home and who have faced local authorities in this capacity. They simply cannot believe that they will receive real help, and expect judgmental treatment, abuse and prosecution for what they have already suffered.

Neoliberal austerity eroded institutions of social security throughout the 2000s. Citizens of eastern European countries encountered the 2008 financial crisis without any safety net. The illiberal turn in 2010 and Viktor Orbán’s ongoing war on the poor has accentuated the situation in Hungary: homelessness has been criminalized and social welfare has been reduced and replaced by tax breaks which favour those with higher, more stable incomes. Since 2012, misdemeanour cases are no longer brought before the courts but dealt with by the police themselves, resulting in ludicrously high fines that often result in jail sentences. Those penalized were, in any case, mostly unable to avoid the circumstances that led to their being fined in the first place. Compounding the vicious cycle, children are separated from their families when a parent is found to be engaging in sex work, or for connected economic reasons, such as inadequate housing conditions. Many of these children will in turn also be forced to prostitute themselves.

A huge number of sex workers and prostitutes end up on the sex market because they have no other option and are then persecuted further for being in that situation. Many flee the country to escape this vicious cycle but end up trapped in trafficking or at the mercy of punters and pimps. The best that many can hope for is to be merely dependent and isolated. These are the people despised by many in western European societies, whose solvent members they provide with cheap sex.

See: Greggor Mattson: The Cultural Politics of European Prostitution Reform, London 2016.

Published 23 February 2018

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Réka Kinga Papp / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Sex in colonial empires and its legacy in Europe today

An interview with Christelle Taraud

Feminist historian Christelle Taraud talks about the patriarchal system for regulating prostitution in France’s colonial empire, a system made by men for men to reserve indigenous women for their own use and control the ‘unruly’ sexuality of men from honour cultures. These issues are covered in ‘Sexe, race, et colonies’ (2018), co-edited by Taraud, which has proved controversial in France for its unsettling imagery.

‘Sex work will disappear the day we abolish capitalism. Until then, let’s talk about labour rights.’ Amaranta Heredia Jaén calls to address the controversial results of anti-trafficking measures.