Jump to the update

On Wednesday 7 January, several of our colleagues were killed in an abominable attack on the editorial offices of the magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris. The shooting of at least twelve people was also an attack on one of the basic principles of an open society: the freedom of speech and expression. In such a situation there can be no buts and no perspectives. And yet, now more than ever, we need “slow journalism”, we need reflection rather than reflexes.

We recommend articles published previously in Eurozine by Kenan Malik, one of our most read authors and an ardent defender of Enlightenment values, secularism and free speech. Is there really something about Islam that makes its followers more prone to violence and intolerance than others? asked Malik a few months ago. Well, he answers, “there is something about Islam that needs challenging. But equally, there is something about secular liberalism, and the blindness and pusillanimity of many secular liberals, the bigotry of many critics of Islam, and the cynicism of many secular governments in their exploitation of radical Islam, that needs challenging too.”

In another article, Malik dissects the cycle of self-reinforcing myths around the Mohammed cartoons since these were first published almost a decade ago. The latter text being one of a series on free speech and the cartoon controversy.

Meanwhile, Eurozine partners have responded in various ways to the events in Paris. Janne Wass of the Helsinki-based Finno-Swedish weekly Ny Tid writes:

“What has happened is a ruthless attack on freedom of expression, a gigantic personal tragedy for those killed and their families and friends, as well as a further blow to anyone trying to build rather than destroy, bridges between cultures and people. It is an expression of how dangerous journalists and dissidents around the world live but also a reminder that freedom of speech is a right that should be used with care.”

Wass traces the roots of Charlie Hebdo back to a French tradition of satire “that for us northerners at times comes across as rather vulgar”. On the other hand, he notes, “no one has ever died of being offended”. Under all these “excesses” awaits us the question “if we should accept that terrorists can threaten us with violence just because we say our piece or if we should support those who defy death in the name of free speech.”

Wass finally finds the answer in the words of Salman Rushdie, first published by English PEN:

“I stand with Charlie Hebdo, as we all must, to defend the art of satire, which has always been a force for liberty and against tyranny, dishonesty and stupidity. ‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.”

Writing in openDemocracy in a similar vein to Rushdie, political scientist Cas Mudde also demands that a robust stand be taken. For it may be “comforting and politically expedient to claim that ‘we’ are attacked because ‘they’ cannot deal with ‘our’ freedoms, particularly freedom of speech.” But opportunist or superficial shows of solidarity, whether on the part of politicians with privileged access to established media channels or citizens confined to social media hardly suffice:

“So, how do we move forward in a constructive manner, strengthening our liberal democracies rather than weakening them by authoritarian knee-jerk reactions? Rather than narrowing freedom of speech further, by limiting it to ‘civil’ speech or by broadening anti-discrimination legislation even more, we should live up to our slogans and truly embrace freedom of speech for all, including anti-Semites and Islamophobes! Similarly, we should criticize and satirize all, from atheists to Christians, from Jews to Muslims, and from Greens to the far right. This requires not only that we all speak out against extremists, but also that we defend those who take them on… even before they get threatened or even killed.”

“For now”, writes New Humanist editor Daniel Trilling, “it’s worth stating that journalists should have the right to publish offensive material without fear of violent retribution. They should have the freedom to publish it, and others should have the freedom to criticize it. Let’s defend those rights.” Trilling concludes: “One effect that terrorism can have is that it scares large groups of people into hating each other; into endorsing stereotypes and restrictive laws they might otherwise not. Let’s resist that too.”

Index on Censorship insists that “freedom of expression is non-negotiable” and calls “on all those who believe in the fundamental right to freedom of expression to join in publishing the cartoons or covers of Charlie Hebdo“.

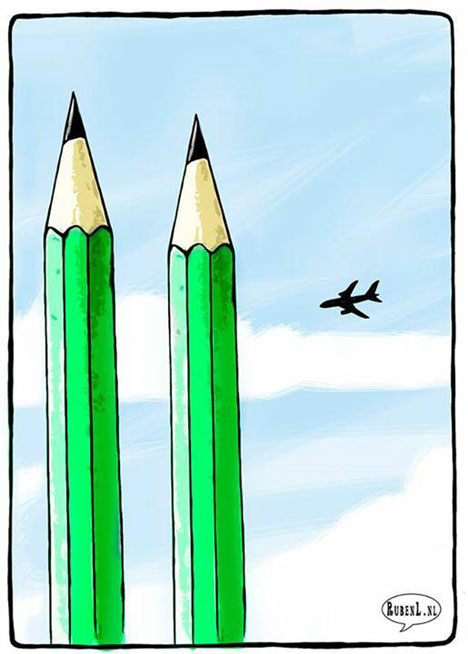

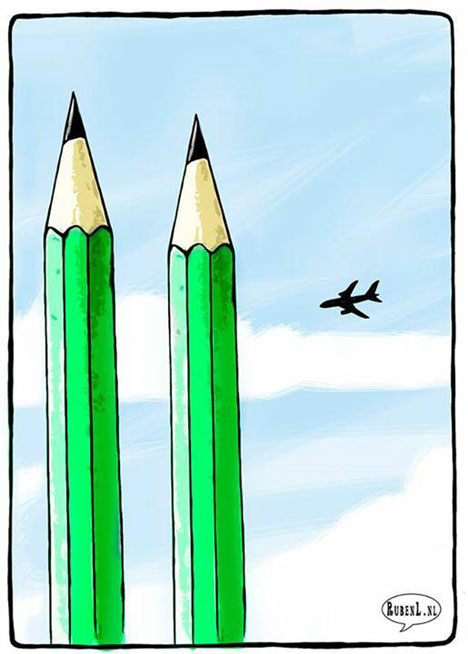

Further, Milana Knezevic, writing for Index, has collected cartoons from around the world, expressing solidarity with the French satirical magazine. Indian cartoonist Kanika Mishra portrays one of the gunmen exclaiming “What the hell? With each bullet, his brush gets bigger?” and Dutch political cartoonist Ruben L. Oppenheimer a plane flying not into the twin towers but twin green pencils.

Updated on 9 January 2014:In a statement available in English and French, the editors of Sens public respond to the assassination of Charlie Hebdo’s entire editorial desk as a rupture in cultural history: an ideology has reared its ugly head “that despises all civil rights and the protection of persons, extolling the hate of all against all.”

So, they conclude: “let’s continue the critical exploration of contemporary conflicts, publish more and more articles that provoke controversies, enter the fight against that which weakens and threatens the critical spirit, further expand our mission to nurture young actors capable of networking; and do so day after day.”

Updated on 13 January 2014:In ResetDOC (and on the Hannah Arendt Center website), Seyla Benhabib

suggests moving the debate on. “It is not enough to repeat the old bromides about Islam and violence; the Koran and the anti-Enlightenment; the need to stand up for the West”, writes Benhabib. For the root of the problem lies in what she terms the “civilizational despair” rampant in war torn countries such as Syria, Libya, Pakistan, Afghanistan and and Iraq. Were this to be overcome, particularly among young Muslims and men, what is really needed is “a regional or international effort on the scale of a Marshall plan for the Arab Muslim world”:

“To focus the debate so narrowly, upon questions of intolerance, blasphemy, apostasy in Islam or the aesthetics of Charlie Hebdo‘s caricatures, is to miss the real point. Until enough changes take place in these societies and until the rage and humiliation suffered by Europe’s Muslims is mitigated through economic and social programmes of successful integration, there will be other targets, and if not caricatures, then telenovellas, operas, video games or other forms of cultural expression which will be attacked. For they are not the cause but simply the occasion for venting rage and despair.”

Res Publica Nowa (Poland) has published a range of responses from the journal’s editors and authors. Like Benhabib, editor-in-chief Wojciech Przybylski also turns to the world stage, particularly with regard to Europe’s role. Commenting on events in Paris from the opening ceremony of the European Year for Development 2015 in Riga, Przybylski warns of the pitfalls present on both the Left (rash attempts to erect a new programme of social engineering upon the grave of multiculturalism) and the Right (the instrumentalization of fears and phobias) of European politics.

He continues:

“Growing fears and Marine Le Pen’s advancement will result in the establishment of an Islamic political party in France, perhaps even at a European level. Putin, together with a raft of continental nationalists, will look on and applaud. This would be grist to their propaganda mill.”

Krzysztof Dolega picks up where Przybylski leaves off and warns that Europe must resist Islamophobia, a phenomenon that if anything only ends up feeding Islamist terrorists with material they can use to support their own abominable goals. Patryk Wisniewski, on the other hand, points to the potential that the hacktivist collective Anonymous offers in combatting jihadist channels online.