While China moves into its fifth decade of extracting rare earths and raw materials, Europe remains stuck between nationalistic industry priorities and democratic principles.

Covid has flooded our lives with online encounters and interactions. We work, minding our image on screen, or struggle to socialise in a hall of mirrors. Geert Lovink considers what we have lost and how we can reclaim our bodies, relationships and shared physical spaces.

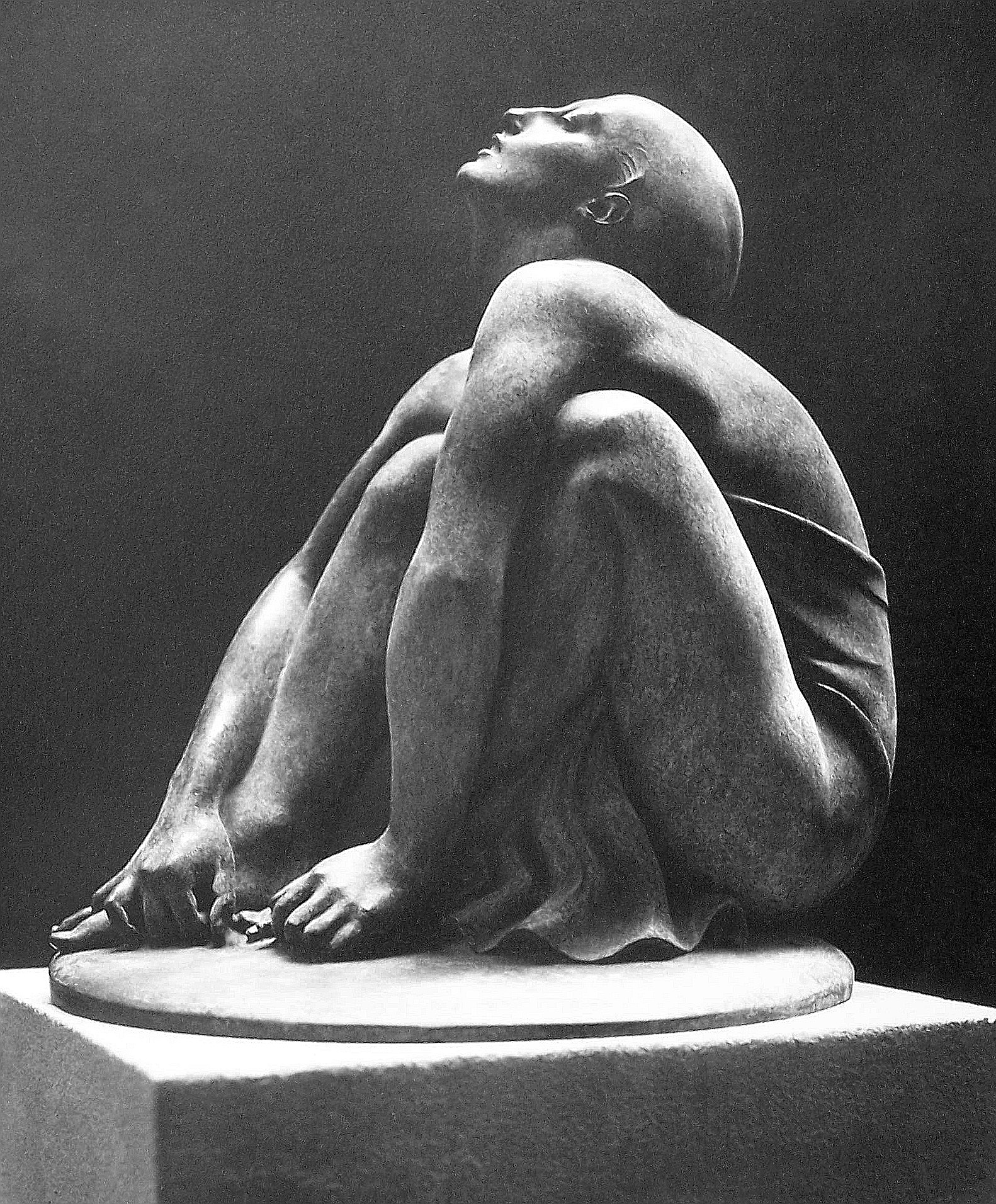

‘The body has been drained of its

sedimented meanings through the

sheer persistence of the recording device

and ceased to be a body productive of meanings

or connotations beyond its materiality and motion.’

Marina Vishmidt

This is it. During the 2020 lockdown, the internet came into its own. For the first time ever, it experienced a sense of completion. Glitches were common enough. A video call lagged, then froze. Laptops or routers had to be restarted. In the early days of lockdown few dared to complain. Mass quarantine did not culminate in a public sense of being trapped in a virtual prison.

Welcome to the electronic monitoring programme. As we continue to develop our online personas, real-life meetings feel clandestine. We are trapped in the videophone future. J. G. Ballard foresaw this ending only in collective mayhem and mutual murder, once flesh re-encountered the world of the living.

Around mid-2020, I began collecting evidence on the trending topic of ‘Zoom fatigue.’ Needless to say, experiences of this kind are not, by any means, limited to Zoom. They extend to Microsoft Teams, Skype, Google Classrooms, GoTo Meeting, Slack and BlueJeans – to name but a few major players. In the ‘corona’ era, cloud-based video meetings have become the dominant private and work environment, not just in education, finance, and health care, but also in the cultural and public sector.

All layers of management have withdrawn into new enclosures of power – the same environment that both precarious freelancers and consultants use to speak to clients. Their lives have little in common, but they all make and take very long hours.

‘Fatigue’ by Cecil Howard (1920-24, stone statue). Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Zoom has multiplied work, expanded participation, and engulfed time for writing, thinking, leisure, and relations with family and friends. Body Mass Index levels increased, affective states and mental health have been hammered, motor coordination wrecked, along with the ability of the brain to negotiate movement through physical space as a result of excess screen time.

Video vertigo is a peculiar condition that also prompts more widespread forms of disorientation. Minka Stoyanova teaches computer programming and spends 20 hours a week on Zoom:

‘My ability for non-work-related social-distancing encounters has gone down greatly,’ she says. ‘While some, craving human contact (no doubt), schedule Zoom cocktail parties and birthday meetups, I dread having to log back into the interface.’1

It is a question of strategy. Should we resist the state of exception, go on strike and refuse to give further online classes, hold management meetings or offer cyber doctors’ appointments? This is easier said than done. Pay checks are at stake. Initially, being able to stay home felt like a privilege that produced a sense of guilt when others had to go out. Now, many fear that video calls are here to stay.

Fast Company forecasts that

‘companies big and small, all over the world, are transforming themselves into a business that is more digital, more remote, and more nimble’.2

Expensive real estate can be sold off, expenses dramatically reduced, and discontented staff effectively isolated and prevented from coming together. The IT management class is already promoting a cost-cutting ‘blended’ model, expecting a backlash after the excessive video conferencing sessions of 2020.

The video dilemma is also intensely personal.

‘If work exhausts my videocall time, I intuitively cut informal video calling with allies, friends, possible collaborators,’ Rotterdam designer Silvio Lorusso observes. ‘This makes me sad and makes me appear rude. It’s a self-preserving attitude that leads to isolation.’

The debate should not be about hanging out on Facetime or Discord with friends for a game night, doing karaoke, holding a book club, or watching Netflix together. Video-time is part of the advanced post-Fordist labour regime, performed by self-motivated subjects who are supposed to be doing their jobs. But then you drift off while pretending not to. Your eyes hurt, your concentration span diminishes, multi-tasking is a constant temptation, and that physically, psychically uncomfortable feeling hums in the back of your head… You’ve heard it all before.

In 2014, Rawiya Kameir defined internet fatigue as the state that follows internet addiction:

‘You scroll, you refresh, you read timelines compulsively and then you get really, really exhausted by it. It is an anxiety that comes along with feeling trapped in a whirlwind of other people’s thoughts.’3

On 22 April 2020, Nigel Warburton @philosophybites on Twitter asked: ‘Does anyone have a plausible theory about why Zoom, Skype, and Google Hangout meetings are so draining?’

Does anyone have a plausible theory about why Zoom, Skype, and Google Hangout meetings are so draining?

— Nigel Warburton (@philosophybites) April 20, 2020

He received 63 retweets, 383 likes, and a few replies. The responses closely mirrored popular diagnoses and advice now offered across the web. The main supposed causes of the ‘fatigue’ that follows Zoom sessions include the brain’s attempt to compensate for the lack of full body, non-verbal communication cues; a sense of constant self-consciousness; engagement in multiple activities with no real focus; and a consistent tugging temptation to multi-task.

Suggested remedies are predictable: take breaks, don’t sit for too long, roll your shoulders, work your abs, hydrate regularly, and integrate plenty of ‘screen free time’ into the day.

For Isabel Löfgren, teaching in Stockholm, Zoom has become a place of residence. The mobile device is her office.

‘Our living rooms have become classrooms. Does it matter what is on display behind you? What does it say about you? If you have a bookshelf in the background, or your unfolded laundry in a pile on the chair behind you, it’s on display and up for scrutiny. What is personal has become public.’

Zoom has become another room in the house – something Gaston Bachelard didn’t predict in his Poetics of Space. Nor did Georges Perec envision a screen as part of the architecture of his fictitious apartment block in the novel Life: A User’s Manual.

But the Czech philosopher Vilém Flusser could, and did. He foresaw ‘the technical image as phenomenology’. Yet, for Löfgren, Zoom functionality is surprisingly simplistic.

‘You can raise your hand and clap like a pre-schooler, chat like a teenager, and look at yourself in your own little square as if peering at a mirror. Showing your face becomes optional, you can go to school in pyjamas, or do it all on the go. Cats, dogs, the boyfriend working in the background, the student who forgot to turn off her mic while she was doing the dishes. Everyone’s Facebooking alongside the lesson.’4

Lorusso describes the dysfunctions of the first days of use:

‘I couldn’t install Microsoft Teams, my camera wouldn’t activate, and, worst of all, the internet connection had hiccups. The connection was neither up nor down; every other attempt it just became super slow. Let me help you imagine my videocalls: all would be smooth for the first five minutes and then decay took over – frozen faces, fractured voices, reboots and refreshes, impatience and discouragement. A short sentence would take minutes to manifest. It was like being thrown back to the times of dial-up connection, but within today’s means of online communication.’5

Then things went ‘normal’. We adjusted to a new interpassive mode. None of us realized that videotelephony was no longer a matter of becoming. This was it. The Completion.

Take a condensed list of uses: social media, work, entertainment, food orders, gaming, watching Netflix, seeing how family and friends are doing, live streams to observe what’s going on for those in hospital. What else do we need during a lockdown? Teleportation, for sure: a way of circumventing trains and airports.

We need to go back to early science fiction novels to read up what we all wished for in the Future. Utopia and dystopia have never come as close to merging as in 2020. All we want is to recover the body. We demand instant vaccines. We want less tech, we long to go offline, travel, leave the damned cage behind.

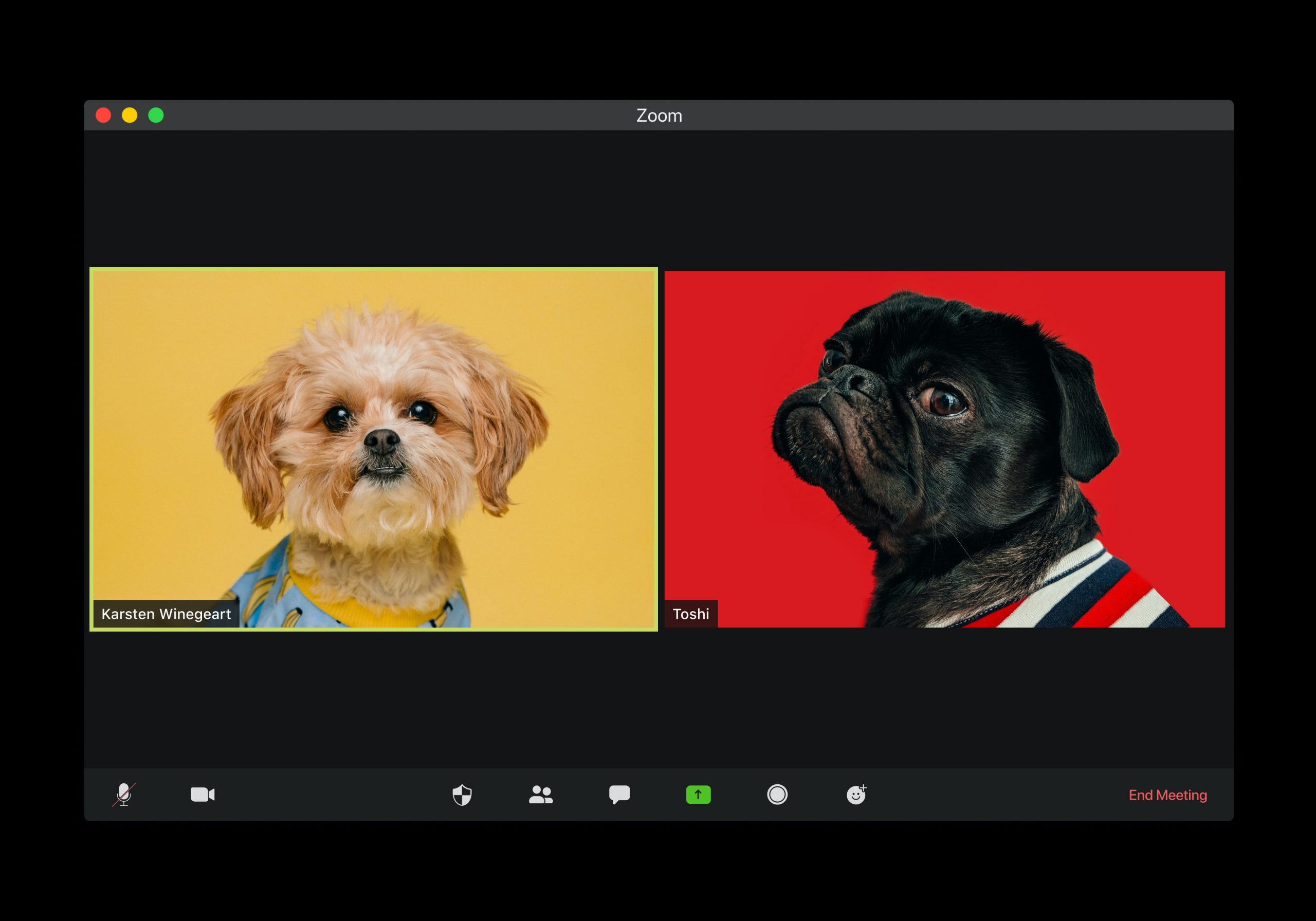

Pug life. Image via visuals on Unsplash.

Back in pre-Covid days, Byung-Chul Han proposed that we were no longer living in a disciplinary society but one defined by performance.6 Since then we have discovered that spending hours in virtual conferences is neither a paranoid panopticon nor a celebration of the self. We are not being punished, nor are we feeling productive. We are neither subjected, nor activated.

Instead, we are hovering, waiting, pretending to watch, trying to stay focused, wondering when we might squeeze in a lunch break or recharge with a caffeine hit. It is questionable whether Zoom fatigue is the product of an ‘excess of positivity’, as Han suggests. Much like the Covid crisis itself, we are being asked to endure never-ending sessions on Zoom. The Outlook Calendar is the new jail warden.

What’s wearing us out is the longue durée, not exhaustion after a peak performance. In response, the system has turned emphatic and switched to worry-mode about our mental state. Screen Time apps and MyAnalytics summaries now inform us how our lives are being wasted as we calibrate our productivity and efficiency to collaborate with colleagues.

It’s hard not to wonder if the IT sector isn’t about to get into bed with big pharmaceutical companies: the society of synthetic performance enhancement is ready for expansion. Soon after the introduction of lockdown, with quarantine in place, the authorities set about investigating whether their pitiable subjects were still coping. There is no hope that this simulacrum of life can ever protect us from accelerating economic and social collapse.

Despite the guilt trips, we are allowed to admit that we’re not achieving much. With society on hold, it is the waiting that tires us out. Trapped in the waiting room, we are being asked – very kindly – to stay in survival-mode, keep going despite the burnout and master the anger. Our task is simply to watch our individual versions of David Wojnarowicz’s personal ‘disintegration’ – barely different to his all-consuming contemplation of the ‘fatality, incurability and randomness of AIDS… so powerful and feared’.7

‘I am utterly zoomed out and exhausted,’

Henry Warwick writes from Toronto.

‘Between watching the nation of my birth (the United States) commit a long slow political suicide and having friends die of Covid and working like a dog while on what is de facto nine months of bio-house arrest, I’m not in a great mood.’

Henry’s summer was spent making video bits and preparing for the delivery of asynchronous class material,

‘…not really a university education – it is a step above a YouTube playlist. Sitting in front of a Zoom window makes it difficult to forge those friendships and networks, and it’s certain a buzzkill for adventure. In addition, there is the issue of Internet Time as I have students all over the world. It’s hard for them to attend a two-hour lecture when it’s 2.00 a.m. where they are. It’s utter madness. Making these videos was a serious time drain. I refuse to give Adobe my money, and Apple screwed Final Cut Pro so badly that I am editing my videos in DaVinci Resolve, which has the benefit of being free-ish. I have never used Resolve, so the learning curve was not insignificant.’8

It took just days for the ‘Zoom fatigue’ trope to establish itself – a sign that internet discourse is no longer controlled by the ‘organized optimism’ of the marketing lobby. Managerial positivism has made way for the arrival of instant doom. According to Google Trends the term made the rounds back in September 2019 and reached its peak in late April 2020.9 That was when the BBC ran a story about it. One expert commented:

‘Video chats mean we need to work harder to process non-verbal cues like facial expressions, the tone and pitch of the voice, and body language; paying more attention to these consumes a lot of energy… Our minds are together when our bodies feel we’re not. That dissonance, which causes people to have conflicting feelings, is exhausting. You cannot relax into the conversation naturally.’

Another interviewee describes how on Zoom

‘everybody’s looking at you; you are on stage, so there comes the social pressure and feeling like you need to perform. Being performative is nerve-wracking and more stressful.’10

Maybe Han’s performance prediction was correct.

As programming teacher Stoyanova noted, the ability to see oneself – even if hidden in the moment – creates a tiring reflective effect, the sensation of being in a hall of mirrors. Educators feel that they are constantly monitoring their own demeanour, while simultaneously trying to project, through the interface, to students. It is like practicing a speech in front of a mirror. When speaking to yourself, you experience a persistent cognitive dissonance. In addition, there is the lack of eye contact – even if students have activated their video – which also makes live lectures more difficult to conduct.

‘Without the non-verbal feedback and eye-contact one is used to, these conversations feel disjointed.’11

Curiously enough, speaking into the void nevertheless kickstarts the adrenalin glands, which certainly isn’t the case when rehearsing in front of a mirror. We have entered a strange mode of performance that aligns with predictive analytics and pre-emption. Even though the audience might just as well not be there, the very fact of performing in the Zoom schedule is sufficient to activate biochemical responses in the body.

In a post on his Convivial Society blog, L.M. Sacasas describes the effect of paying so much attention to one’s self:

‘We are always to some degree internally conscious of ourselves, of course, but this is the usual “I” in the “I-Thou” relation. Here we are talking about something like an “I-Me-Thou” relation. It would be akin to having a mirror of ourselves that only we could see present whenever we talked with others in person. This, too, amounts to a persistent expenditure of social and cognitive labour as I inadvertently mind my image as well as the images of the other participants.’12

Online video artists Annie Abrahams and Daniel Pinheiro point to the rarely discussed effects of delay.

‘We are never exactly in the same time-space. The space is awkward because we are confronted with faces in close up for long time spans. We first see a face framed like when we were a baby in a cradle as our parents looked down upon us. Later it became the frame of interactions with our lovers in bed. This makes it that while video-conferencing, we are always connected to something very intimate, even in professional situations.’

In a passage titled What is Seen and Not Seen, posted in April, the Journal of Psychiatric Reform advises psychotherapists to ‘redefine the new frame prior to the commencement of video therapy’ for online psychotherapy sessions.13

Abrahams and Pinheiro also observe that it is impossible to detect much detail in the image we see.

‘Video conferencing is psychologically demanding because our brains need to process a self as body and as image. We lack the subtle bodily clues for the content of what someone tells. Our imagination fills the gaps and makes it necessary to process, to select what to ignore. In the meantime, we are continuously scanning the screen (there is no overview and no periphery). We are never sure we are “there”, that the connection still exists, and so we check our own image all the time. We hear a compressed mono sound, all individual sounds are mixed into one soundscape.’14

Isabel Löfgren responds that we should think of Zoom as a ‘cold medium’ – one which demands more participation from the audience, according to Marshall McLuhan’s concept of cold and hot media.

‘The brain needs to fill in the gaps of perception, which makes our brains (and our computers) go on overdrive.’

In terms of camera angles, Löfgren adds that we are constantly looking at a badly framed medium-shot of other bodies.

‘We have no sense of proportion in relation to other bodies, we also lose the “establishing shot” of the room. The close-up shot used for emotional closeness to the subject on the other side of the camera is eliminated with the lack of eye contact, no “pheromonal connection”. The Zoom terminology is correct, our experiences of others occur in “gallery mode”.’15

New York cultural theorist Dominic Pettman regularly tweets about Zoom frazzle. His main learning outcome is ‘not dying.’ He admits he is still using Skype ‘ironically’. In a tweet he refers back to his 2014 critique of MOOCs, an almost forgotten online .edu hype that anticipated the existing online teaching default of 2020.

Some weeks into lockdown, the question arose why video conferencing was so exhausting. Zoom fatigue is ‘taxing the brain’, people complained.16 Why are classes and meetings on Skype, Teams and Google Hangout so draining? This was expressed not as some sort of interface critique but as an existential outcry. Popular articles on Medium name it as such. Common titles include variations of

‘Do you have “Zoom Fatigue” or is it existentially crushing to pretend life is normal as the world burns?’

and

‘The problem isn’t Zoom Fatigue — it’s mourning life as we knew it’

Varied multiplicities of voices, moods and opinions expressed via parallel chat channels or integrated polling and online voting have not been widely promoted as yet. We feel forced to focus.

Keep your eyes on the camera, our digital alter-ego whispers through our earphones.

The inertia upholds contradictions – until the body gets depleted, bored, distracted and ultimately collapses.

‘365 Days – Day 208 – Migraine’ by Auntie P on Flickr.

Please provide less, turn the camera off. The number one piece of popular advice on combatting Zoom fatigue is simply, ‘do it less’, as though that’s an option. (‘You don’t hate Zoom, you hate capitalism.’). Should we be designing indicators of group sentiment?

In what way can we fast-forward real-time team meetings? More backchannels, for sure; less ongoing visual presence. But wait, isn’t there already enough multi-tasking happening? If anything, we long for intense and short virtual exchanges, followed by substantial offline periods.

According to Sacasas, video conference calls are

‘physically, cognitively, and emotionally taxing experience as our minds undertake the work of making sense of things under such circumstances. We might think of it as a case of ordinarily unconscious processes operating at max capacity to help us make sense of what we’re experiencing.’17

We are forced to be more attentive, we cannot merely drift off. Multi-tasking may be tempting, but it is also very obvious. The social (and sometimes even machinic) surveillance culture takes its toll. Are we being watched? Our response requires a new and sophisticated form of invisible day-dreaming, absence in a situation of permanent visual presence – impossible for students, who are not afforded their grades unless the camera stays on.

Video conferencing software keeps us at bay. Having fired up the app and inserted name, meeting number and session password, we see ourselves, as part of a portrait gallery of disappointing personas that constitutes the Team, occasionally disrupted by partners who walk into the room, a passing pet, needy kids and the inevitable courier ringing the doorbell.

Within seconds you are encapsulated by the performative self that is you. Am I moving my head, adjusting myself to a more favourable position? Does this angle flatter me? Do I look as though I’m paying attention?

‘Thanks to my image on the screen, I’m conscious of myself not only from within but also from without. We are always to some degree internally conscious of ourselves.’

Sacasas describes the experience as a double event, which the human mind experiences as if it were real.

Why do I have to be included on the screen? I want to switch off the camera, be absent, invisible, a voyeur, not an actor – until I take the stage and appear out of nowhere. I have the right to be invisible, right? But no, the software lords have decided otherwise and gifted the world with the virtue of visible participation. They demand total contribution.

The insistence on 24/7 mindfulness can only lead to a regressive revolt, an urge to take revenge. The set is designed to ensure that we stay focused, all of the time, making the fullest possible contribution, expending maximum mental energy.

Meanwhile, I long to be frozen like an ancient marble bust, neatly standing in a row with other illustrious figures, on the palace corridor, turned on by a click, brought to life much like the figures in Night at the Museum.

You have to take a break and OMG, you hate so much having to dress up for that video call (but you do it anyway). Bored and tired of the emotional labour, you change your living room background to a tropical beach to cheer up and shroud the situation. How can we blow up the social portrait gallery, with its dreadful rectangular cut-outs? Jailed inside the video grid you drift away from the management meeting and enter a virtual Rubik’s version of Velasquez’ Las Meninas (1656).

‘Las Meninas’ with Droste Effect II., from cea+ on Flickr.

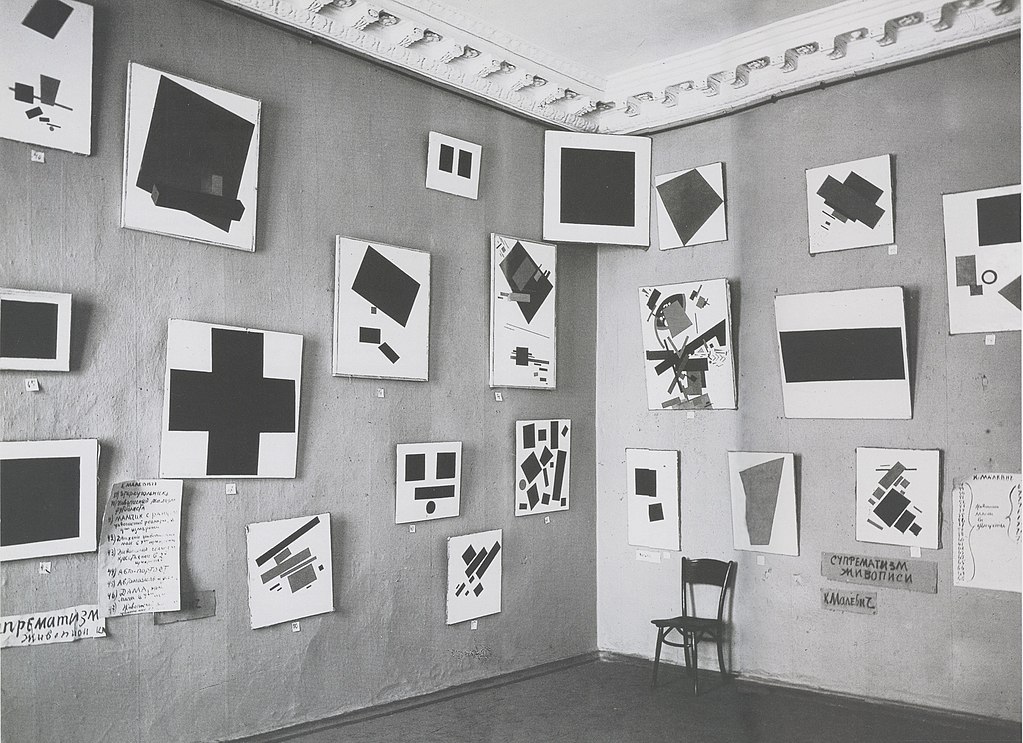

Then you move on to the next room, the Kazimir Malevich 1915 Suprematist exhibition.

A section of Suprematist works by Kazimir Malevich exhibited for the first time in Petrograd in 1915. The photo is public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

After which you wake up and realize you’re back inside your own sad version of The Brady Bunch opening credits.

Inside the Brady Bunch opening credits. Image from Wikipedia.

You’re on Zoom, not roaming inside some artwork. We’re not a photograph or video file either. We happen to be alive, and have to come to terms with being inside Existential Reality (ER).

Writing for Artforum, Paula Burleigh observes that

‘the most pervasive of Covid imagery has little to do with the actual disease: it is the digital grid of people congregating virtually on Zoom for “quarantini” happy hours, work meetings, and classroom instruction.’18

The grid Burleigh describes as a hallmark of minimalist design and modernist art,

‘conjures associations with order, functionality, and work, its structure echoed on graph paper and in office cubicles’.

In his two-part History of the Design Grid, Alex Bigman describes how the system of intersecting vertical and horizontal lines was invented in Renaissance painting and page layout. This lead to the development of graphic design. The assumption that images are more dynamic and engaging when the focus is somewhat off-centre is something video conferencing designers have yet to take on board.

The Haussmann-style grid cuts through any rational divisions between boxed-in subjects. Individuals are unable to spill-over into the space of others, except when they gossip on a backchannel or use the ‘vulgar’ theatrics of Zoom bombers who, early on in lockdown, carried out raids on open sessions until they were expelled.

As Burleigh concludes, ‘the grid is rife with contradictions between what it promises and what it delivers.’ The individualized squares are the ‘second modernity’ post-industrial equivalent of a Le Corbusier housing nightmare: we are sentenced to live in our very own utopian prison cells. Within these condensed volcanic flows of violent energy, one may find tragic normalcy at best, while deep despair is the standard deviation.

‘Our very own utopian prison cells’: the Sainte Marie de la Tourette convent in France, designed by Le Corbusier. Photo by Alexandre Norman on Wikipedia.

A media-archaeological approach to Zoom would require a return to 1990s cyber phantasies of mass live castings such as Castanet – a system designed by dotcom ‘push technology’ start-up Marimba (‘a small group of Java Shakespeares’, according to Wired).19

The idea was to make the Web to look more like TV by overthrowing the browser paradigm (which the app, in part, later succeeded in doing). Much like Zoom, Teams and Skype, the Castanet application had to be downloaded and installed in order maximize bandwidth capacity. Two decades later the basic choices are still more or less the same, with Microsoft (owner of Skype and Teams) still active as a key player.

Each individual webcasting technology uses its own, proprietary mix of peer-to-peer and client-server technologies. Zoom, for instance, looks smooth because it compresses and stabilizes the signal of the webinar into one stream – instead of countless peer-to-peer ones that constantly need updating. It also pushes the user into a position of ‘interpassivity’: a passive audience mutes its audio and shuts up, much like a pupil listening to a teacher in the classroom.

This is in contrast to free software peer-to-peer architectures (such as Jitsi) that go back to the free music exchange platform Kazaa. This is, ironically enough, also listed as one of the inspirations of Skype, which revolves around collaborative exchanges between equal partners. So, are we watching a spectacle as an audience or working together as a team? Are we permitted to vote, intervene, freely chat?

On the nettime mailinglist Michael Goldhaber notes that there is something inherently flawed about the user interface.

‘I usually stand and move around when lecturing, sometimes making large gestures. Just sitting at a desk or wherever is sure to be fatiguing. Doing this in a non-fatiguing way will require fundamentally re-thinking the system of camera, mic and screen with respect to participants.’20

The sad and exhausting aspect of video conferencing can also be attributed to the ‘in-between’ status of laptops and desktop screens that are neither mobile and intimate, such as the smartphone with its Facetime interface, nor immersive such as Oculus Rift-type virtual reality systems.

Zoom fatigue arises because it is so directly related to the ‘bullshit job’ reality of our office existences. What is supposed to be personal, turns out to be social. What is supposed to be social, turns out to be formal, boring and (most likely) unnecessary. This is only felt on those rare occasions when we experience flashes of exceptional intellectual insight and when existential vitality bursts through established technological boundaries.

In her Anti-Video-Chat-Manifesto, digital art curator Michelle Kasprzak calls on us to turn off our video cameras.

‘DOWN with the tyranny of the lipstick and hairbrush ever beside the computer, to adjust your looks to fit expectations of looking “professional”. DOWN with the adjustment of lighting, tweaking of backgrounds, and endless futzing to look professional, normal, composed, and in a serene environment. DOWN with not knowing where to put your eyes and then recalling you need to gaze at the camera, the dead eye in your laptop lid.’21

She calls upon us to

‘refuse to fake living in an IKEA showroom with recently-coiffed hair, refuse to download cutesy backgrounds which take up all our CPU and refuse to fake human presence.’

Michelle also asks the question who else is present during our calls:

‘Hello NSA, hello Five Eyes, hello China, hello hacker who lives downstairs, hello University IT Department, hello random person joining the call.’

Cultural anthropologist and research consultant Iveta Hajdakova, currently based in London, writes:

‘Last week I had three nightmares, all related to remote work. In one, I was fired because of something I said when I thought I was offline. In the second, my colleagues and I were trying to get into an office through a tiny well. We were hanging on ropes and one of them became paralysed, which I think was a dream version of a Zoom freeze. The third nightmare was about me losing track of my tasks. I woke up in panic, convinced I had forgotten to send an important email.’

In the early days of lockdown, she struggled with headaches and migraines. Luckily, she writes, these have gone

‘perhaps due to a combination of factors, having a desk and a more ergonomic setup, being able to get out of the flat, limiting non-essential screen and headphone time, and adopting lots of small changes to my routine. The head and the ears are feeling much better now but something isn’t quite right, as the nightmares signal. I’ve started feeling disconnected and I think this is not merely a result of social isolation but of a more profound sense of disorientation.’

Hajdakova is noticing a growing sense of confusion and uncertainty.

‘I’m losing a sense of what people at work are thinking, feeling, what they need and expect, what I’m doing well and what I can improve, which has a detrimental effect on my self-confidence. To be clear, everyone at work is providing these in abundance but with so much time passing without seeing my colleagues face-to-face, I feel like I am losing the ability to anchor our interactions in embodied human beings and shared physical environments.’

Zoom is on its way to becoming a social environment acting like a re-mediation of office life gone by.

‘In the beginning, recreating the office experience over video calls worked because all of us still had the shared reference point,’ Hajdakova continues. ‘We were imitating the real office and it was a fun challenge we could all participate in. But the more we’re removed from the office in space and time, the more I’m forgetting what it is that we’re imitating.

We’re creating something new, a simulacrum of the office. The difference between the two is: when I imitate the office, the office is still there and my efforts are judged on how close I get to resemble the real thing. But if I create a simulacrum of the office, I no longer need the real thing. To adapt to the simulacrum, I’ve started incorporating other aspects of my digital life into my remote working life so that my life and work online feels more whole… I don’t want to be just a face and voice on Zoom calls, an icon on Google docs, a few written sentences, I want to be a person… Social media helps so I’ve been posting on social media a lot.’

Friedrich Nietzsche once noted:

‘When we are tired, we are attacked by ideas we conquered long ago’.

When Facebook is experienced like a panacea, we know something must be deeply wrong. But why is this feeling of discontent so hard to pin down? The inert state is essentially regressive.

‘The more I try to be a real person, the more I’m getting trapped in the simulation of myself,’ Hajdakova says. ‘I’m communicating and sharing just to remind people I exist. No, it is to remind myself that I exist… Like McLuhan’s gadget lover, like Narcissus, staring at his own image.’

We are losing a sense of reality, memory and confidence, Iveta argues,

‘but also losing a sense of understanding for other people. Just knowing that they feel X or Y but having no way of connecting with them through some kind of mutual understanding. In general, Zoom is traumatising for me because of the way my mind works – I need physical things, shared environments etc., otherwise, I lose not only confidence but also memory and motivation.’22

Danish interface design researcher at Aarhus University, Søren Pold comments:

‘At your desktop you can change your view, mute your microphone and stop your camera or change background and filters, but you can’t see if others are looking at you and they can’t see if you’re looking at them. There’s only a slight overview and control of the sound you’re receiving and transmitting. I have often struggled with figuring out how to transmit sound from the videos I’m showing or with trying to ensure that the sound of the computer fan does not take over. Zoom becomes a layer, an extra operating system, that takes over my computer and leaves me struggling to get through to the other software I am aiming to control. Besides, Zoom prioritizes loud and deep voices to more quiet and higher pitch voices and thus creates a specific speaking order, prioritizing male speakers.’

The new video filter that adds a mask, a funny hat, a beard or a lip colour demonstrates that Zoom is watching how you’re watching through face tracking technologies. This Zoomopticon, as Pold calls it, is the condition in which you cannot see if somebody or something is watching you, but it might be the case that you’re being watched by both people and corporate software.

‘Zoomopticon has taken over our meetings, teaching and institutions with a surveillance capitalistic business model without users being able to define precisely how this is being done.’23

Is a different kind of Zoom possible? We have found the experience draining, yet coming together should empower. What’s wrong with these smooth high-res user interfaces, accompanied by the lo-res faces due to shaky connections? It’s been a dream televising events and social interactions, including our private lives. How can we possibly reverse the Zoom turn?

Is the ‘live’ aspect important to us or should we rather return to pre-produced, watch-‘em-whenever videos? In education this is not a marginal issue. There is a real, time-honoured tension between the all-consuming exciting ‘liveness’ of ‘streaming’ and the detached flat coolness of being ‘online’.24

Six months into lockdown, online conferences on spirituality and self-awareness began to offer counter-poison to their own never-ending sessions. They staged three-day Zoom events (twelve hours a day). They introduced Embodiment Circles,

‘a peer-led, free, online space to help us stay sane, healthy and connected in these uncertain and screen-filled times. The tried and tested 1-hour formula combines some form of gentle movement, easy meditation and sharing with others.’25

The organisers promote

‘embodied self-care for online conferences. With such an amazing array of speakers and other offerings, the conference-FOMO is real. Let’s learn a few self-care practices that we can apply throughout the conference, so we arrive at the other end nourished, inspired, and well-worked… rather than drained, overwhelmed, or with a vague sense of dread and insufficiency.’26

Given this context, should we be talking in terms of ‘harm reduction’?

Online wellness is the craze of the day: our days on Zoom include breaks with live music performances, short yoga and body scan sessions. It is Bernard Stiegler’s pharmakon in a nutshell27: technology that kills us will also save us. If Zoom is the poison, online meditation is the antidote.

After the Covid siege, we will proudly say: we survived Zoom. Our post-digital exodus needs no Zoom vaccine. Let us not medicalize our working conditions. In line with the demonstration on Amsterdam Museumplein (2 October 2020) where students demanded ‘physical education’, we must now fight for the right to gather, debate and learn in person. We need a strong collective commitment to reconvene ‘in real life’ – and soon. For it is no longer self-evident that the promise to meet again will be fulfilled.

Private email exchange after a public call on the nettime mailing list, 3 July 2020.

Private email exchange, 26 June 2020.

https://www.platformbk.nl/en/remote-work-demand-dail-up/, posted 12 June 2020.

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society, Stanford University Press, 2015.

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives. A Memoir of Disintegration, Canongate Books, Edinburgh, 2017. See also here.

Private email exchange, 1 October 2020.

Private email exchange, 3 July 2020.

L.M. Sacasas, ‘A Theory of Zoom Fatigue’, 21 April 2020, https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/p/a-theory-of-zoom-fatigue

A. Abrahams, D. Pinheiro, M. Carrasco D. Zea, T. La Porta, A. de Manuel, D. Casacuberta, P. Gatell, and M. Varin, ‘Embodiment and Social Distancing: Projects’, Journal of Embodied Research, 2020, Vol. 3 (2), 4 (27:52), DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/jer.67

Private email exchange, 3 October 2020.

L.M. Sacasas, ‘A Theory of Zoom Fatigue’, 21 April 2020, https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/p/a-theory-of-zoom-fatigue.

Silvio Lorusso, ‘Remote Work? Demand Dialup’, 12 June 2020, https://www.platformbk.nl/en/remote-work-demand-dail-up/

Michael Goldhaber, nettime mailing list, 7 July 2020.

Ref. in Silvio Lorusso’s essay, https://michelle.kasprzak.ca/blog/writing-lecturing/anti-video-chat-manifesto

Quotes from a private email exchange, 21 September 2020. See also her text on the same issue: http://thisbloodyplace.com/ill-just-never-know/

Private email exchange, 6 October 2020.

See Alan Liu’s definition: ‘Cool is information designed to resist information’. (The Laws of Cool, The University of Chicago Press, 2004, p. 179). We could update Lui’s phrase ‘I work here, but I’m cool’ to ‘I hangout here, but I am cool’.

Quoted from communication related to https://icpr2020.net/

Pharmakon: a Greek word meaning both poison and remedy. Philosopher Bernard Stiegler (1952-2020) argued that technics was a pharmakon, simultaneously curative and toxic.

Published 2 November 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Geert Lovink / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

While China moves into its fifth decade of extracting rare earths and raw materials, Europe remains stuck between nationalistic industry priorities and democratic principles.

The race for green transition supplies is on. But where’s the thrill in metals, discreet and hidden yet widespread? Mining, intensive due to low concentrations, throws up waste elements like arsenic. Space cowboys and deep-sea dredgers contest environmental stability more than China’s monopoly, based on 40-years of involved processing. Health and recycling regulations are a must.