Terror, collaboration and resistance

Russian rule in the newly occupied territories of Ukraine

Russia is using methods tested in Crimea and the separatist republics to impose its control on the Ukrainian territories occupied since February 2022. Those who remain not only find their lives in ruin but must also make impossible choices in the broad spectrum between collaboration and resistance.

On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine and in the following months occupied large parts of the north, east and south-east of the country. By early April, however, the resistance of the Ukrainian army had forced Russia’s military leadership to withdraw its troops from the Chernihiv, Sumy and Kyiv oblasts and from parts of the Kharkiv oblast. The latter was then almost entirely de-occupied following the Ukrainian counteroffensive in September. In November, Russian troops were forced to leave Kherson, the only oblast capital captured since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Occupied Ukrainian territories in the south-east – parts of the Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts – nevertheless remain under Russian control. Following the sham referendums between 23 and 27 September, Moscow annexed these four Ukrainian regions and declared them part of the Russian Federation.

What do we know about Russia’s changing goals, political projects and policies in the newly occupied territories? How do the occupiers combine repression, propaganda and humanitarian aid to promote loyalty among the local population? What dilemmas do local Ukrainian authorities, local businesses and educational institutions face under Russian occupation? How do they make the difficult choice between resistance and collaboration, between self-sacrifice and self-preservation?

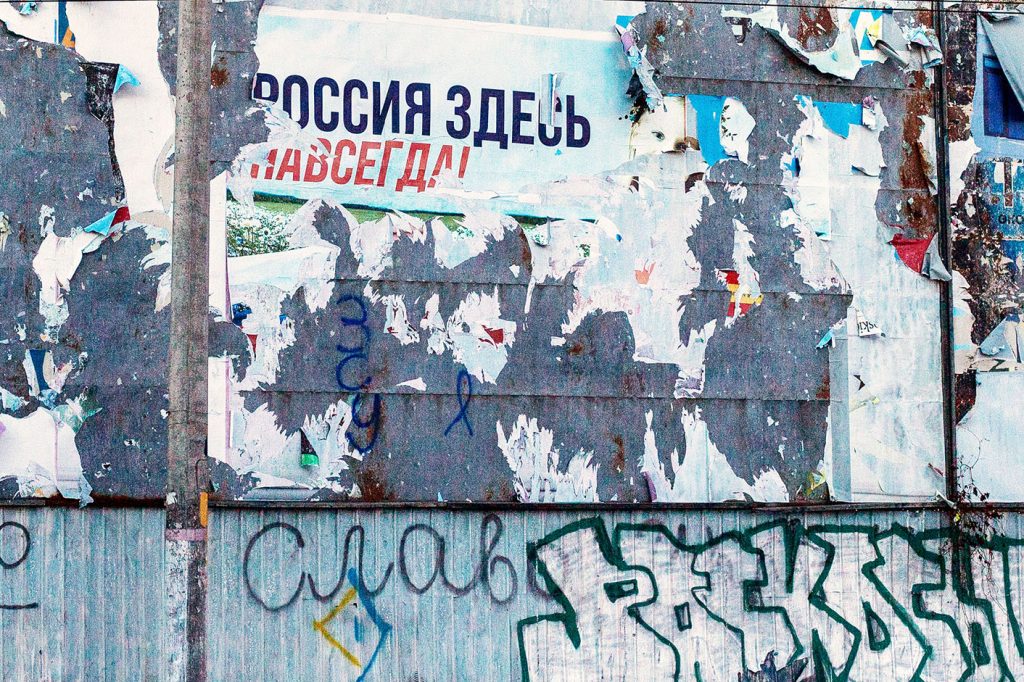

‘Russia is here forever.’ Kherson, January 2023. © Anastasia Magazova

Occupation since 2014

Russia annexed Crimea and established control over parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014. Today it is deploying many of the methods it used there in the territories occupied since February 2022. But there are some important differences.

Russia’s occupation of Crimea in spring 2014 took advantage of the political crisis in Ukraine and the pro-Russian mobilization on the peninsula. The territory of Crimea was annexed through a hastily organized quasi-referendum that – although not recognized internationally – was used to legitimize the ‘unification’ of Crimea with the Russian Federation. The annexation was completed almost without violence and Moscow claimed that it was not involved militarily. One year later, Putin publicly admitted that a ‘special operation’ had in fact been carried out in Crimea.

Residents of Crimea became Russian citizens overnight; rejecting a Russian passport was complicated and costly. The integration of Crimea into the Russian political, legal and administrative system took place in a matter of weeks. Repressions were targeted at pro-Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar activists, many of whom left Crimea for political reasons, while the rest of the population was won over by promises of a better life.

The occupation of parts of the Donbas was different. Moscow supported pro-Russian separatists throughout eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014, enabling them to proclaim ‘people’s republics’ in the cities of Luhansk and Donetsk (the so called LNR and DNR). When the Ukrainian army tried to restore Kyiv’s control over the insurgent areas, Russia’s army intervened covertly. The result was a war between the Ukrainian armed forces and Russian-backed separatist forces that saw over 14,000 dead and millions become internally displaced.

Unlike in Crimea, however, Moscow did not aim to annex the controlled parts of the Ukrainian oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk. Rather, it tried to use its vassal ‘republics’ to gain influence within Ukraine. Moscow insisted on a reform of the Ukrainian constitution that would have integrated the ‘people’s republics’ into Ukraine as autonomous entities, and to legitimise their leaderships through elections. Kyiv also wanted to re-integrate these regions, but on different conditions. It insisted that only when Ukraine had regained control over the border with Russia could elections be held in accordance with the Ukrainian constitution.

The influence of Ukrainian institutions and actors in the ‘people’s republics’ diminished very rapidly. Although below the threshold of a formal annexation, Moscow’s military, political and economic support led to a de facto integration of the separatist territories into the Russian Federation, not least by issuing Russian passports to the local population.

Ukraine accepted neither the annexation of Crimea nor the occupation of parts of the Donbas. Nevertheless, the situation stabilised somewhat between 2015 and 2022. Kyiv conceded that the return of the occupied territories might be possible only through political and diplomatic channels. In 2016 Ukraine created a Ministry of the Temporarily Occupied Territories whose task was to protect the rights of Ukrainian citizens living there and on the contact line, as well as of internally displaced persons.

The fragile stability ended abruptly on 21 February 2022, when Russia officially recognised the Donetsk and Luhansk ‘people’s republics’ and promised them military support against attempts by Ukraine to ‘invade’ them. Then, on 24 February, Russia launched its full-scale attack on Ukraine, which it dressed up as a ‘special operation’.

Since then, Сrimea and the ‘people’s republics’ have served as springboards not only for military operations, but for establishing control over the newly occupied territories. Fleeing Ukrainian citizens are held in so-called ‘filtration camps’ and prisons are used to detain Ukrainian activists and prisoners of war. Teachers are sent to Crimea for training in Russian language and history, and Ukrainian children go there for ‘patriotic re-education’ in summer camps.

Local elites’ recent experience of integration into the Russian political, administrative and economic system is now being exploited in the newly occupied territories. Officials from the DNR and LNR were deployed to prepare the referendums in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, while officials from Crimea and Sevastopol were involved in organising referendums in the occupied oblasts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia.

Occupation 2022

Unlike in 2014, Russia is now openly attempting a full-scale military invasion. It no longer hides its goal of territorial expansion – a neo-imperial land-grab, legitimized by nothing but historical arguments. In this new phase, however, Russia’s attempts to use the political instruments already applied in Crimea and Donbas have had limited success.

The ‘people’s republics’ scenario failed some weeks after the start of the invasion. Russia lacked control over the oblast capitals (except for Kherson) and failed to mobilize a critical number of the local elites. In Kherson, the oblast council adopted, by a large majority, a declaration asserting the territorial integrity of Ukraine, including the Kherson oblast. The city council of Kherson backed the declaration and the regional prosecutor opened a criminal investigation against Russia for violating Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Several large rallies against the occupation took place in Kherson in the subsequent weeks, making the lack of public support for a ‘people’s republic’ scenario obvious.

Referendums in the occupied territories were the next available alternative, but they entailed major problems for the Kremlin. Unlike the Crimea referendum in 2014, they had to be conducted amidst a full-scale war. Moreover, the actual frontline did not coincide with the administrative boundaries of the territorial units that Moscow was planning to annex. While the Kherson and Luhansk oblasts were largely under Russian control, a significant part of the Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts (including the city of Zaporizhzhia) still had to be conquered. Annexing parts of Ukraine that Russia did not control meant turning the ‘special military operation’ outside Russia’s borders into a war on its own territory.

In order to be a credible manifestation of popular will and thus serve as legitimation of Moscow’s territorial acquisitions, the referendums had to be thoroughly prepared. The task was handed to Sergei Kirienko, the first deputy head of the presidential administration responsible for domestic politics, who had been assigned responsibility for Donbas and other newly occupied territories in April 2022. A team was assembled with expertise in organising fraudulent elections in Russia. Polls commissioned by the Kremlin for internal use showed that support for annexation by Russia was low, meaning a lot of propaganda work would be needed to win at least some degree of sympathy on the part of the population and local elites. There were also multiple organizational challenges: the absence of a loyal administrative apparatus; both passive and active resistance from Ukrainians, including acts of sabotage; and a moving frontline.

All these difficulties caused the referendums to be postponed again and again. Speculations intensified before the ‘Victory Day’ commemoration on 9 May, traditionally used by Moscow to drum up pro-Russian sentiment in the former Soviet states. Since the ‘special military operation’ was billed as a war against ‘Ukrainian Nazism’, the date would have been an ideal opportunity to celebrate the choice of ‘liberated’ Ukraine to be part of Russia. But it was obviously too early. The deputy head of the Russian-appointed ‘military-civilian administration’ in Kherson even suggested that the area be annexed to Russia by virtue of a presidential decree, without a popular vote – which would not have been recognised by the West anyway. However, Moscow chose to preserve the appearance of legality.

In the Russian media, speculations and rumours continued into the summer. It was suggested that after the referendums the occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts would become ‘Northern Tauria’, thus restoring the boundaries of the old tsarist province.1 Others claimed that the Kremlin was considering combining the four territories annexed after the referendums into a new federal district.

The plebiscite was expected to be held beginning of September, at the same time as the local and regional elections in Russia. Instead, a Ukrainian counter-offensive allowed the Ukrainian army to de-occupy the Kharkiv oblast almost entirely. On 5 September, the referendum in the Kherson oblast was postponed for ‘security reasons’. Two days later, Andrey Turchak, head of the United Russia party, said that it ‘would be right and symbolic’ to hold the referendums on 4 November, Russia’s Unity Day.

But the Kremlin saw no point in delaying further. Ukraine’s counteroffensive forced Moscow to conduct the referendums despite not fully controlling any of the four regions. Far from the final accord in consolidating Russia’s control over the occupied territories, the referendums looked like a desperate attempt to maintain the status quo on the battlefield and to deter Kyiv from advancing further.

The referendums were held in the four partially occupied oblasts between the 23 and 27 September 2022. Not surprisingly, the results announced by Moscow showed near total support for annexation, ranging from 99.23% in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts to 87.05% in the Kherson oblast. The referendums were internationally rejected as a sham and failed to provide even limited legitimacy for Russian rule over the local Ukrainian population.

On 30 September the territories were formally annexed to Russia. Using the annexation to raise the stakes, Russian officials threatened to use ‘all possible means’ to protect its newly acquired territories. But in November, Russia lost control over Kherson, the only oblast capital it had managed to occupy in 2022. The annexation, which was meant to repeat the ‘successful’ 2014 Crimean scenario, had failed to stabilize the situation on the ground or to secure Moscow’s control over the occupied territories.

The annexation posed Russia with the problem of reconstructing the vast territory devastated by war. It created also legal dilemmas. Because the boundaries of the annexed territories have not been clearly defined, Russia’s unilaterally declared new national borders have become fuzzy. Moreover, significant parts of Russia’s new territories are now ‘under Ukrainian occupation’, while the quasi-statehood of the two ‘people’s republics’ has to be unmade.

Regardless of its illegality, however, the annexation has created a new reality for the Ukrainian population on the related territories, leaving little room for compromise and forcing people to make final choices.

‘I love Kherson.’ January 2023. © Anastasia Magazova

The reaction of the Ukrainian state

In 2014, the political crisis in Ukraine weakened state institutions, with massive anti-Ukrainian propaganda confusing the populations in the east and south. In 2022, however, the Ukrainian state and Ukrainian civil society have demonstrated significant resilience. The army is better prepared and there is no pro-Russian mobilization from below.

The response of the Ukrainian state to Russia’s occupation has also been more consolidated. De-occupation through military means remains Kyiv’s main strategy, given there is little hope of it regaining its territories through negotiations with Russia. There is not much the government can do to counteract Russian policies in the occupied territories, except to try to retain the loyalty of Ukrainian citizens and to prevent collaboration. It looks for ways to communicate with the local population in the occupied territories and emphatically assures citizens that their country has not abandoned them. It encourages people to document crimes by the occupiers (such as looting of property and harvest) and supports local resistance.

The Ministry of Reintegration tries to enable people from occupied, besieged and war-ravaged areas to flee to Ukrainian-controlled territory and offers support to internally displaced persons. It makes efforts to retrieve Ukrainian citizens forcefully relocated to Russia (especially children). At the same time, it disseminates advice on how to behave in the event of forced deportation, on how men in the occupied territories can avoid being called up for military service, and on what behaviour Ukraine considers collaboration and how to avoid being forced to do it. Early on, the government warned that any Ukrainian citizen who participated in the organization of referenda would be held accountable.

Pension payments and other social benefits are now paid without humiliating verification procedures, no matter where the eligible person is located. The administrations of occupied cities have moved to Kyiv-controlled territory and keep in touch with their citizens via Telegram and other channels. The administration of Mariupol, for example, has opened centres in several Ukrainian cities where displaced people can receive support and come together. Similarly, a drop-in centre for displaced persons from Kherson was established in Zaporizhzhia.

The humanitarian situation in the newly occupied territories

The situation in the occupied areas varies greatly and often changes dramatically. The decisive factors are the duration of the occupation, the military situation and proximity to the front, and the degree of destruction and depopulation.

The occupied areas in the Kyiv, Sumy and Chernihiv oblasts in the north of Ukraine were liberated after only four weeks. There, Russia never seriously tried to establish a pro-Russian administration or win the loyalty of the population. Instead, local residents were treated indiscriminately as potential partisans and saboteurs. Those who seemed suspicious were tortured and killed, while women, children and the elderly were detained for days and weeks, often under inhumane conditions.

Many towns were largely destroyed when captured by Russian troops. Three examples are Mariupol in the Donetsk region, Izyum in the Kharkiv region and Rubizhne in the Luhansk region. The majority of the population has fled, while the situation for those who remain is dramatic. Izyum, back under Ukrainian control since September, is recovering from its war wounds only slowly. In Rubizhne, which is still under Russian occupation, locals are afraid of heavy fighting as the frontline approaches. Mariupol has been turned into a showcase of reconstruction by Moscow, but everyday life remains hard.

The Kherson region and parts of the Zaporizhzhia region fell under the control of the Russian army without major fighting. But since then, the humanitarian situation has deteriorated considerably. After several waves of exodus, only a third of the population of Kherson was still in the city in August. The forced ‘evacuation’ in October when the Russians decided to leave Kherson further emptied the city.

The population throughout the newly occupied territories lives in fear and insecurity. After the Ukrainian state was eliminated, violence and looting became a part of everyday life. What the Ukrainian troops and authorities discovered after regaining control of Kherson confirmed (and exceeded) eyewitness reports. Numerous torture chambers were found, for example.

The occupiers fill the power vacuum in their own way. The streets are patrolled by the militia of the ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ or the notorious troops of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. The Russian National Guard (Rosgvardiya) is also deployed in the occupied territories. The occupiers are building up a new police force, partly recruited from officials from the dissolved Ukrainian police. All these forces are hardly likely to restore public security or to win the trust of the population – on the contrary, they are often involved in the day-to-day criminality themselves.

Many people lost their jobs as businesses closed or left. In the first months of the occupation, public sector workers – doctors, teachers, social workers – often received their salaries either late or not at all. Likewise, there were delays or cuts in pensions and child support benefits. Even if the money was transferred, it often could not be withdrawn in cash. Soon, the occupiers started to exercise pressure on public institutions and to appoint Russia-loyal cadres. The aim was to cut all ties to the Ukrainian state and instead make people dependent on supplies from the occupiers. People were forced to take pensions and social benefits in roubles.

Moscow’s propaganda claimed that the Ukrainian government abandoned its citizens. Many Ukrainian pensioners, especially in rural areas, do not have a bank account. Before the Russian invasion, they received their pensions in cash at home from the local post office. In the Kherson oblast alone, 70,000 pensioners relied on the postal service. In August, after delivery had become increasingly difficult, Ukrposhta stopped operating in the occupied territories. As a partial solution, the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Affairs now allows pensioners to set up an internet bank account for social benefits. As soon as they leave the occupied territories, they can receive their pensions in cash.

In many places, water, electricity and district heating networks are damaged. Mariupol is the best-known example, but the situation is similar in many smaller cities. Medical care is extremely difficult to access. Many doctors have fled, and hospitals lack bandages, medicines and much more. In Kherson, 90% of pharmacies had closed by May. Drugs for cancer patients, diabetics and other patients who depend on regularly preparations are lacking throughout all the occupied territories.

Food supply remains a problem. Most Ukrainian supermarkets in the occupied territories closed soon after the invasion because of disrupted supply chains and pressure from the occupiers. In the first months, prices for everyday goods skyrocketed. Only the local farmers were offering fruit and vegetables at affordable prices – but only because they could no longer deliver to the free areas of Ukraine. Street trade, shortages and queues looked for many like a return to the 1990s. Although food and medicine supplied from Russia and Russian supermarket chains have since arrived, the availability of daily products is by no means back to previous levels.

In addition to all this, the fighting is causing severe environmental hazards: particularly forest and field fires and water pollution. The danger of mines is also widespread. In the liberated areas, the removal of explosive devices will take years. This hugely affects agriculture. In the summer, de-mining squads were forced to burn fields of crops that were ready for harvest. This is to say nothing of the impact that an accident at the occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant would have.

Russia’s policies in the occupied territories

Where the frontline has stabilized, Russia has started to set up ‘military-civilian administrations’ meant to replace the Ukrainian authorities. Initially, however, the local Ukrainian administration continued to function in many places with limited competences. Because hardly anyone was willing to collaborate with the occupation forces, this was the only way to maintain basic municipal services. For example, the city administration of Kherson under mayor Ihor Kolychaev continued to operate for almost two months after the capture of the city. It was not until 25 April that the occupiers took over the town hall and took down the Ukrainian flag.

The occupiers often resorted to kidnapping and torturing politicians, officials and journalists to persuade figures of local importance to collaborate. A prominent early case was the mayor of Melitopol, Ivan Fedorov, who was kidnapped on 11 March. The following day, about 2000 people in the occupied city publicly demanded his release. He was soon exchanged for nine prisoners of war and honoured by the Ukrainian president for not having succumbed to physical and psychological pressure. Since then, hundreds of people have been abducted or arrested; some were seized at home after collaborators had drawn up lists of names and addresses; others were arrested at checkpoints after having their smartphones checked or after interrogation in the filtration camps.

Some abductees have since been released, often after being beaten and tortured, but others remain missing or have been found dead. In the occupied territory of the Zaporizhzhia region alone, 415 people were abducted between March and July 2022, according to official figures. Euromaidan activists and people known for their pro-Ukrainian position, along with members of nationalist groups and Ukrainian military veterans, are most at risk. The occupiers believe that they could build an underground armed resistance movement.

One way for Russia to secure the obedience of the Ukrainian population has been humanitarian aid. The pattern was the same everywhere. First, established routes for food transports were blocked, in order to create a shortage. Aid from the Ukrainian side was obstructed and, in some places, supplies appeared to have been stolen and re-packaged as Russian aid. Finally, trucks from Russia brought food, with the occupiers presenting themselves as benefactors.

Another way has been to buy the loyalty of the locals, especially vulnerable social groups. Many pensioners received a one-off payment. On ‘Victory Day’ on 9 May, President Putin issued a decree giving 10,000 roubles (€130) to all veterans of the ‘Great Patriotic War’ in the ‘liberated territories’. Footage of people gratefully receiving these crumbs were all over Russia’s state-run television news stations, which are also broadcast in the occupied territories.

Information control and propaganda have been crucial means of establishing permanent rule over the occupied territories. Shortly after the invasion, the occupiers switched off Ukrainian television channels. Their frequencies are now used to broadcast Russian stations. Some local newspapers were also taken over. In Mariupol, the occupiers set up public viewing screens to assert Moscow’s version of the capture of the city to the few residents who remained.

No less important is control over telephone traffic and the internet. In early June, the local mobile phone and internet provider in the Kherson region, ChersonTelekom, was forced to cut connections with the Ukrainian network. The regional network was later connected to the Russian network via a provider set up in 2014 specifically for annexed Crimea. When retreating from Kherson in November, Russian troops destroyed the entire telecommunications and internet infrastructure.

In the other occupied territories, Russia is in control over the flow of communication and data and has enforced a regime of censorship that is even harsher than in that Russia itself. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter are blocked, as are Google and YouTube in many places. The messenger service Viber, which many people in Ukraine use for data traffic with their bank, is also blocked. There is also surveillance. Because Ukrainian SIM cards no longer work in mobile phones, people have to buy new cards from Russian providers. SIM cards are only sold on presentation of an identity card, meaning that all activities can be attributed. The Russian special services can now track all telephone calls and internet traffic.

The economic detachment of the occupied territories is also underway. Ukrainian banks had to close their branches and can now only be accessed online, if at all. In spring, the hryvnia became increasingly hard to find in ATMs. At the end of May, the occupiers announced the introduction of the rouble in Kherson oblast, initially in parallel with the Ukrainian hryvnia. Pension, benefits and wages were issued by the occupation authorities only in roubles. Local entrepreneurs were forced to open rouble-denominated accounts and carry out all money movements in roubles. Yet despite the pressure on shopkeepers and market traders to change, the hryvnia long remained the preferred currency. Since 1 January 2023, the circulation of the hryvnia in the occupied territories has been banned.

At the beginning of June, the Russian state-owned bank Promsvyazbank announced that it would be setting up branches in the newly occupied parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Because Promsvyazbank is subject to western sanctions and can no longer issue cards from the providers Visa and Master Cards, residents must accept a card from the Russian payment system Mir. Other banks from Russia were, however, hesitant to get involved in the occupied territories. Only the MRB bank, which is registered in South Ossetia and has had branches in the two ‘people’s republics’ for several years (gaining a bad reputation), announced at the end of July that it would open a branch in the Kherson oblast.

After the annexation of the four Ukrainian oblasts at the end of September, their integration into the Russian financial system became inevitable. In December 2022 the Bank of Russia opened local branches on the occupied territories. Russia’s Federal Tax Service has also since opened its offices on the occupied territories.

Before the annexation, an important instrument for the consolidation of the occupying power was the ‘passportisation’ of the local population. On 25 May, President Putin issued a decree simplifying the issuing of Russian passports to residents of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. Similar rules have applied to the two ‘people’s republics’ since 2019. However, Russian passports were not popular: enthusiasm for the new citizenship was limited not only by loyalty to Ukraine, but also fear of being forcefully recruited into the Russian army. The Russian authorities therefore increased pressure on people to apply for Russian passports. Anyone who ran a business, no matter how small, had to re-register it according to Russian legislation. This required holding a Russian passport, as did registration of car number plates and the sale of land.

After the annexation, all residents on the occupied territories automatically became Russian citizens. Like after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, those who rejected Russian citizenship were given one month to have their decision filed.

‘Soft power’: Symbolic politics

A central element of the occupation policy is Russification. This concerns language, culture and history. Street names, public advertisements, official documents and media are now in Russian; public use of the Ukrainian language is seen as a sign of disloyalty. Museums, cultural centers, and libraries have received a new pro-Russian management. Ukrainian artists, writers and musicians who remained have been forced to collaborate. Those who refuse risk their lives. In September, the conductor Yuriy Kerpatenko was shot dead by Russian soldiers after he refused to take part in a concert in occupied Kherson. In the Kharkiv region, the writer Volodymyr Vakulenko was killed by the occupiers. His body was found in a mass grave in the city of Izyum after the city’s liberation.

The historical narrative propagated by Vladimir Putin that Ukraine is an artificial state without its own history and identity is at the core of Russian propaganda. Russia, instead, appears as the historic, ancestral land of the Ukrainians. A whole arsenal of symbolic politics is being deployed to this end. In Kherson, posters with portraits of and quotations from the likes of Aleksandr Pushkin, the army commander Aleksandr Suvorov and Prince Grigoriy Potemkin were put up in May, at the initiative of the Kremlin party United Russia. The posters praise the imperial expansion in the northern Black Sea region in the 18th century and declare that ‘Kherson is a city with a Russian history’. The common past presumes a common future: the slogan of the referendum campaign was ‘Forever with Russia’. ‘Russia Day’ (12 June), which has been a bank holiday since 1992, was also celebrated in the occupied territories. Ironically, the day commemorates the Declaration of Sovereignty of the Russian Soviet Federative Republic. Ratified by the Russian parliament in 1990, it contributed to the dissolution of the USSR that Moscow is now so eager to re-create.

But Russian imperial history does not seem to be enough to win the loyalty of Ukrainians. More promising is the appeal to the Soviet past, especially among the older generation. Streets have been given back the old names they had before the de-communisation drive of 2015. Whether this is on the initiative of local collaborators with resentments against the Maidan, or that of the Russian occupiers is unclear. Statues of Lenin have also been reinstalled, for example in Henichesk and Nova Kakhovka. Again, this is somewhat ironic, since in his speech shortly before the invasion Putin blamed Lenin for the creation of the Ukrainian state.

Of course, the Russian authorities do not care about Lenin or Soviet ideology. But a neo-Soviet Ukraine seems to them an antipode of today’s post-Maidan Ukraine, which the Kremlin calls ‘an anti-Russian project’. Memorials commemorating the Euromaidan, the Heavenly Hundred – the name given to the more than 100 people killed by sniper fire on the Maidan – or the Ukrainian soldiers killed in the Donbas over the past eight years have therefore been vandalized or destroyed. Ukrainian national symbols such as the trident have also been removed, of course.

But at the centre of Moscow’s symbolic policy in the occupied territories are the ‘Great Patriotic War’ and ‘Victory Day’. For twenty years, the victory in the Second World War has dominated the Putin regime’s politics of memory. In 2014, the memory played a major role in justifying the annexation of Crimea and the pro-Russian mobilization during the so-called ‘Russian Spring’. Today, the invasion of Ukraine is passed off as a fight against ‘Ukrainian fascism’, a repetition of the Russian mission of 1941–1945.

Moscow had hoped that the anniversary of the victory on 9 May would have a pro-Russian propagandistic effect in the occupied territories. Soviet-style victory celebrations were organised targeting the older generation, with commemorative marches by ‘Immortal Regiments’ and public performances of Soviet songs. The occupiers claimed – falsely – that celebrating Victory Day was prohibited in Ukraine and that ‘liberated’ Ukrainians were now free to do so. On 9 May the occupation authorities raised the Victory Banner with hammer and sickle next to the flag of Russia, once again hoping for the power of Soviet symbols.

Probably the most bizarre symbol, however, was ‘Babushka Z’ which in spring haunted the occupied territories as well as Russia on walls, T-shirts and postcards. The meme was based on a short video of Ukrainian soldiers bringing food to an old woman, who comes to meet them with a red Soviet flag and greets them as liberators. When she realises they are Ukrainian soldiers, she returns the food. For Russia’s propagandists, this was a godsend. Sergey Kirienko, one of Russia’s highest officials, unveiled a statue in honour of the ‘heroine’ during his visit to Mariupol in May; soon after he was made responsible for the occupied territories.

Babushka Z, Mikhaylovka (Saky District, Crimea), June 2022. Source: Wikimedia commons; author: Mitte27

Ukrainian resistance

Immediately after the invasion of the Russian troops, large pro-Ukrainian demonstrations against the occupation took place in many cities including Kherson, Melitopol and Enerhodar. Even in villages, video footage shows angry people shouting at the occupiers or blocking tanks.

Less visible, but even more widespread and continuing to this day are other, not explicitly political forms of resistance. Many people have organised themselves informally, to provide neighbourly help, support the old and infirm, organise evacuations, and covertly bring humanitarian aid to the occupied areas. One can speak of the resilience of Ukrainian civil society, or simply admire people’s civil courage.

Organizers of protests or those mistaken for activists ran the risk of being kidnapped, tortured and killed. Nevertheless, pro-Ukrainian flash mobs continued to be organised, quickly dispersing before patrols arrived on the scene. Even now, Russian flags are secretly removed from public places, buildings are painted with Ukrainian symbols and colours, leaflets are distributed announcing the imminent arrival of the Ukrainian army, warning against taking Russian passports, or ridiculing collaborators. A yellow ribbon and the Ukrainian letter Ї (absent in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet) have become symbols of Ukrainian resistance in the public space.

Another form of resistance is civil disobedience. In Kherson in June, when the new administration’s ‘Chief of the Education Department’ summoned local teachers and school headmasters, most of them left the meeting when they learned of the occupation authorities’ plan to replace the existing curriculum with one modelled on the Russian system.

The most radical form of resistance is targeted sabotage: the destruction of bridges, railway lines or military infrastructure and attacks on collaborators. In some cases, these attacks may have been less about politics than disputes over the redistribution of resources. Overall, however, there are indications that a partisan movement supported by the Ukrainian army and secret services is emerging in the occupied territories.

‘Ruscist go home – as long as you are still alive!’ Kherson, January 2023 © Anastasia Magazova

Fifty shades of collaboration

Every occupying power depends on collaboration. To gain control over occupied territories, the occupiers need people with access to local networks, knowledge of local conditions and administrative experience. In in Crimea in 2014, Russia could rely on a widespread willingness to cooperate. In 2022, recruiting collaborators proved more difficult.

On 3 March, the Ukrainian parliament passed two laws criminalising collaboration. The first law criminalises cooperation with the aggressor state, its armed units or occupying authorities; it also penalises public support of the occupying power and the public denial of the Russian attack on Ukraine and the occupation of parts of its territory. The law provides for imprisonment of up to 15 years. The dissemination of pro-Russian propaganda, particularly in educational and academic institutions, is also punishable by imprisonment of up to 3 years. The second law restricts the rights of convicted collaborators. They are barred from running for public office, having access to state secrets or serving in the army. In the first nine months of the war, the National Police registered about two thousand criminal proceedings for collaborationism; 347 people are under the status of suspects and 206 indictments have been submitted to the courts. Some sentences have already been passed, mostly in absentia, because the offenders were in the occupied territories.

The NGO Chesno (‘Honest’), in cooperation with the National Agency for the Prevention of Corruption, has created a database recording collaborators. The Ministry of Digital Transformation also asks anyone with information about collaborators in the occupied territories to report them via a chatbot.

The legal definition of collaboration is one thing, however the behaviour of people under occupation and their possible motives is another. Collaboration ranges from open support of the occupation out of ideological conviction to collaboration in a particular situation, perhaps after being threatened with violence or otherwise blackmailed, or in expectation of financial gain. Often it is not possible to distinguish between the two. In many cases, ideological convictions go hand in hand with the opportunity to take revenge on political opponents.

Those who supported the annexation of Crimea and the ‘Russian Spring’ in 2014, and who lost their posts or were convicted of anti-Ukrainian activities or fled to Russia to avoid arrest, now have an opportunity to regain power. Today’s collaborators count former MPs or mayors among their ranks. One prominent example is Volodymyr Saldo, the former mayor of Kherson (2002–2012) and MP (2012–2015), who has been the head of the collaborationist Kherson military–civilian administration in Russian-occupied Ukraine since April 2022. The same goes for former members of the secret services, the police and the army who had come into conflict with the authorities or harboured resentments towards their employer.

Among the collaborators are also many local MPs from the Opposition Platform, one of the successors of Opposition Bloc, which itself had succeeded ex-President Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions. At the beginning of the Russian invasion, the activities of the Opposition Platform were suspended on the ground of suspected ties to Russia and its parliamentary faction was dissolved.

But other parties are not without black sheep. One well-known case is Oleksiy Kovalyov, who sat in the Ukrainian parliament for Volodymyr Zelensky’s party Servants of the People, but returned to his hometown in Kherson oblast in April. He claimed that he wanted to be with his constituents, but in fact he returned to protect his business interests. In July, it became known that Kovalyov was a member of the Russian-appointed ‘government’ of Kherson oblast; as a result, he was wanted for high treason. Following a failed assassination attempt in June, he was killed in August.

Some bloggers and local journalists have also made themselves available to the occupiers. Some took the occupiers’ side out of ideological conviction. Kiril Stremousov, for example, had moved in pro-Russian circles for years, spreading conspiracy ideologies during the Covid 19 pandemic. After the occupation he became the deputy commander in Kherson. He died in a car accident in Kherson on 9 November, just before the Russian retreat. Other collaborators are motivated by their business interests and seek a favourable deal with the occupation authorities. Different motives often complement one another.

The longer occupation continues, the greater the pressure to collaborate becomes. This applies as much to chiefs of municipal services as to the heads of kindergartens. In summer 2022, preparations for the referendum and the beginning of the school year left little space for compromise. The government in Kyiv also increased the pressure, issuing strong warnings about the criminal penalties for collaboration, and particularly for participating in the organization of the referendum. But the Ukrainian government has since refrained from further legal measures, since to criminalise the acquisition of a Russian passport, for example, would in its eyes be counterproductive. The annexation of the four Ukrainian oblasts to Russia in September 2022 further narrowed the possibility of avoiding collaboration.

Between a rock and a hard place: mayors and business owners

From the outset, the occupiers put pressure on the mayors and municipal councils in the occupied areas, knowing that their cooperation and support was central to legitimising the occupiers’ actions and demoralising their opponents. Those who resisted were physically and psychologically harassed; many were abducted, some were tortured or even murdered. Those who organised evacuations and humanitarian aid risked imprisonment and even execution, while those who worked to keep communal services running risked being denounced as collaborators. Those who fled were able to save themselves and their families but were often accused of being selfish by the people they had left behind.

The mayor of Kherson, Ihor Kolychaev, remained in office for the first two months of the occupation. He publicly declared his loyalty to the Ukrainian state, supported the pro-Ukrainian protests and fulfilled his official duties. The Ukrainian president awarded him a medal for bravery. The Ukrainian flag flew on the roof of the town hall until the end of April.

In interviews with Ukrainian media, Kolychaev stressed that he could not possibly leave the city and abandon the citizens who elected him. But he also criticised the Ukrainian government for failing to provide clear guidelines to public officials like him. Most of the inhabitants of Kherson trusted him, but rumours also emerged about why the occupiers left him in office for so long. He was also accused of having private interests, principally in agri-business.

But perhaps the occupiers had calculated that it was to their advantage to retain the mayor of a large city known for his pragmatism. Kolychaev had spoken out against blocking Crimea’s water supply via the North Crimean Canal before the Russian invasion, for example. In fact, his case was unique. The chief elected representatives of all the other 49 municipalities and counties of Kherson oblast either fled, were arrested, or openly collaborated.

Kolychaev didn’t remain an exception for long, however. On 25 April, Russian soldiers occupied the Kherson town hall and installed a new administration. Kolychaev had to vacate his office but announced that he would remain in the city and continue to hold carry out his duties. He was arrested on 28 June on charges of collaborating with Ukrainian saboteurs and has not been seen since.

The case of Vadym Boichenko, the mayor of Mariupol, is different. A manager in the business empire of oligarch Rinat Akhmetov (Metinvest, among others), he was elected mayor in 2015. In 2019, he ran for the Verkhovna Rada on the list of the pro-Russian Opposition bloc. But he increasingly acted independently and was popular among the citizens of the city for his progressive policies. One day, when Mariupol was already encircled by the Russian army, Boichenko was not able to return to the city from the nearby countryside.

However, he formally remained in office and was active as mayor on the widely-used social media channel Telegram. In real terms, however, he could do very little to help the inhabitants of Mariupol in their immense suffering. His Telegram messages angered many, who did not believe his story and felt that the mayor should stay with his fellow citizens. This discontent was exploited by the occupiers for their propaganda.

Business owners in the occupied territories also face major challenges. Their supply chains have been cut and their produce and property has often been looted (a particular problem for agriculture, which has lost harvest and equipment). Unless businesses concede to pressure and collaborate, they are taken over by the occupiers or pro-Russian competitors.

Leaving the occupied territories is often not an option: aside from a sense of social responsibility, particularly among business providing for the critical needs of the local population (e.g. pharmacies and bakeries), there are costs involved in re-locating to the territories under Ukrainian control. The Ukrainian state cannot provide financial assistance in such cases, meaning that relocation is a major financial burden, especially for larger businesses.

Those who decide to stay risk being charged with collaboration by the Ukrainian authorities. Under the new law against collaboration, ‘conducting economic activities in cooperation with the aggressor state’ is an offence. Cooperation is defined, among other things, as registration with the occupational authorities (e.g. temporary permission for agricultural business); paying taxes to occupational authorities; and working with suppliers from Russia. This placed local businesses in an almost impossible situation.

In August, however, the Ukrainian government recommended amendments to the law: some exceptions were to be allowed, particularly in agriculture, logistics, the production and sale of medicines, humanitarian aid and other activities indispensable for the wellbeing of the population. Under these amendments, only voluntary collaboration would be punishable. These amendments have yet to be adopted by parliament, however.

The education system

While the whole Ukrainian education system has faced enormous challenges since the 24 February 2022, the situation has been particularly dire in the occupied territories. With the imposition of martial law on the first day of the invasion, schools and other educational institutions were closed and children were sent on holiday for a fortnight. When it became clear in March that the war was not going to end soon, the Ministry of Education recommended moving to digital remote learning. Where this was not possible, schools were recommended to offer children psychological support. Schools and other institutions were also asked to keep students and their families informed on the local situation and on options for evacuation, and to help organise civil defence.

Countless school buildings were damaged or destroyed and hundreds of thousands of pupils and teachers fled to other parts of the country or abroad. According to the Ministry of Education, as of beginning of June, 26,000 Ukrainian teachers had left the country. Most of them continued to teach online.

‘Welcome to the land of knowledge’ is written on this bombed-out school in Avdiivka in Donetsk Oblast, eastern Ukraine. © Anastasia Magazova

As of May 2022, around 800 schools were in occupied areas. The new administrations pushed for them to reopen, in order to demonstrate to citizens a return to ‘normal life’ and to celebrate the ‘peace’ that Russia has supposedly brought to the people there. Remote learning, which Ukrainian schools were already practised in after two years of pandemic, became an act of resistance.

At the beginning of April, the Ministry of Education officially had allowed schools to decide for themselves when the school year would end. They were also instructed to skip exams and to transfer all students to the next grade. The Ministry promised that every graduate would receive a certificate. Student from the occupied territories had to collect their certificates in Ukrainian-controlled territory, however.

The Central Baccalaureate – which had successfully reduced corruption in the education sector since being introduced in 2008 – was adapted to the current situation. For the school year 2021/2022, central examinations in four subjects were replaced by one unified examination. This was held in the non-occupied parts of the country and other European countries on three different days. At the first session in July, 187,000 candidates took the exam in 250 locations in Ukraine and in 40 cities across Europe: an impressive feat of organization.

At the beginning of the 2022–2023 school year in September, the occupation authorities pushed ahead with forced integration into the Russian system. The language of instruction is now Russian and the curriculum being adopted from Russia, which has the greatest impact on the teaching of history. But it is not just about the language of instruction and the curriculum. Moscow announced that the schools must educate children to become ‘Russian patriots’.

The law on collaboration criminalises the ‘dissemination of the aggressor state’s propaganda in educational institutions’ and ‘actions aimed at promoting the aggressor state’s academic agenda’. The Reintegration Ministry has recommended that teachers stop teaching whenever Ukrainian standards can no longer be met and has promised to continue paying their salaries. Although the law considers teaching the Russian curriculum to be a form of collaboration, it goes unpunished if teachers can prove they did so under duress.

In anticipation of the new school year in September, the authorities appointed by Moscow ratcheted up the pressure on teachers and directors. Some were arrested. Those who refused to collaborate were replaced and volunteers were recruited, including many from Russia. As from the end of July 2022, 200 teachers from Russia were reported to have signed up for deployment to Ukraine. Parents were pressured; according to some reports, they were threatened with deprivation of their parental rights if they refuse to register their children with a Russian-controlled school.

Mariupol is a particularly striking example of the Russification of the school system. Soon after Russia seized control of this devastated and depopulated city, the occupation authorities announced that the school year would be extended until 1 September. Summer courses were organized for children who remained in the city to ‘improve their Russian language skills’.

By May 2022, the occupying forces had identified just 53 teachers in Mariupol who were prepared to collaborate – in a city whose population had numbered half a million before the invasion. These were sent to the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don for retraining. After completing the programme, they were awarded an official diploma as teachers of Russian and Russian history. Teachers and educators from the Donetsk ‘People’s Republic’ were also sent to Mariupol to make up for the shortage of teaching staff.

There have been numerous initiatives by teachers forced to flee Mariupol who wish to continue teaching according to Ukrainian standards. One of them, a private ‘lyceum’ set up by teachers from Mariupol’s School No. 56, provides online lessons for children regardless of where they are. But remote learning is not a permanent solution, of course. It requires internet access, poses problems for working parents with younger children, and put families at risk as the occupation authorities sanction ‘underground’ schooling.

In 2017, Ukraine had begun on an educational reform aimed at bringing the school system into line with European standards. The reform made significant progress, despite the unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic. The war is now jeopardizing these efforts.

The situation is similar at universities. Loyalist administrations were installed in the occupied territory and new rectors appointed. The Kyiv Ministry of Education announced that the Ukrainian universities on the occupied territories were evacuated and that any work that takes place on their premises under the management of the occupiers will not be recognised.

Kherson State University, which like the other universities in the occupied territories switched to online teaching on the first day of the invasion, is a significant example. Following the Russian capture of Kherson in early March 2022, academics from other regions of Ukraine, Europe and the USA organised a lecture series entitled ‘Academic Bridge’ as a show of solidarity for the university’s students. Anonymous registration was possible for security reasons. In April, most of the administration of Kherson University went to Ivano-Frankivsk in western Ukraine to keep teaching running online from there. Many professors and students had fled to other parts of Ukraine or abroad.

On 14 June, Russian forces in Kherson took control of the main building and arrested the vice-rector Maksym Vinnyk. Later it was announced that he was safe and in Kyiv-controlled territory. In need of a new ‘rector’, the occupiers appointed Tetyana Tomilina, who had been known for her pro-Russian attitude since 2014.

Tomilina’s biography is that of a typical collaborator. She is a graduate of Kherson University, with diplomas in Russian language and literature, and law. For several years she was the director of the Academic Lyceum at the university, which prepared pupils for university studies. In 2014, she promoted the ‘New Russia’ project on social media. She lost her position as a result, for which she blamed her pro-Ukrainian colleagues. In a television interview in 2015, she claimed that there was a secret American bio-lab in Kherson that posed a threat to the population.

Interviewed about her plans after her appointment as rector, Tomilina promised to crack down on alleged corruption and said that Kherson students would be allowed to complete their MA and PhD degrees at the Moscow State Pedagogical University. An assassination attempt was carried out on Tomilina on 12 September, which she survived.

When Russians retreated from Kherson in November, the occupied ‘Kherson University’ was evacuated too and continues to offer teaching online, according to Russian sources. The rectorate of Kherson University, located in Ivano-Frankivsk, warned students that degrees from universities taken over by the enemy would not be recognised outside Russia. Ukrainian degrees, on the other hand, would allow access to postgraduate courses in Europe. The university advertises special scholarships for students from Kherson. In the current academic year, classes continue online.

De-occupation: Immediate and mid-term challenges

According to the UK Ministry of Defence, Ukraine has, as of mid-December, been able to de-occupy 54% of the territory invaded by Russia since February 2022. But there is a long way to go before the wounds of war will be healed in these areas. Ukraine faces numerous challenges that prevent a quick recovery. One is security: the task of demining is huge and reports about residents being injured by explosives appear daily. Even more deadly are the rocket attacks. Kherson, as well as the parts of the Kharkiv oblast liberated in September, are being shelled by Russia incessantly. Kherson, Kupiansk, and Vovchansk were almost intact upon de-occupation; they are now steadily being destroyed.

Kherson City entrance after de-occupation, January 2023 © Anastasia Magazova

A related problem is de-population. Much of the population was deported to Russia before de-occupation and de-population has continued due to Russian shelling. A good example is the Lyptsi community in the Kharkiv oblast, on the Russian border. It includes 17 villages, all of which were de-occupied in mid-September. Of its 13,500 inhabitants before the invasion, just 1,900 were left in November. Some villages are completely empty.

Key infrastructure – roads and bridges; transport connections; electricity and gas networks; water supply; heating; communications – have been largely destroyed. Their reconstruction poses enormous financial, organizational and technical challenges. Healthcare services, which are in strong demand given that the elderly constitute the majority of those who remain, are often hardly available. This is a particular problem in the countryside. The local authorities are trying to organize mobile medical brigades and make use of telemedicine, which requires mobile power generators and Starlink terminals.

Because much of the housing stock has been damaged, many people have nowhere to return to. Many administrative buildings, schools, cultural centres and local hospitals have been destroyed or looted. It is a major logistical operation to provide even basic services: post, pensions, bank services, retail, fuel, etc.

The return of young people and families with children also depends on the availability of jobs. Even before the Russian invasion, employment in the Ukrainian province was a problem. The recovery of these areas depends on their former inhabitants returning, but because of the continuous shelling, heating problems and blackouts, the authorities are hesitant to let people back to their homes.

The de-occupation of Kherson once again showed that the Russian mantra about Ukraine as a failed state has nothing to do with reality. The Ukrainian police, SBU and the military-civil administration arrived on the day the Russians withdrew and supported the Ukrainian Army with de-mining and stabilization measures. Efforts were immediately made to restore the internet and telecommunications infrastructure; Starlink terminals were installed in the city centre to allow people to call their family and friends in Ukraine and abroad. The Ukrainian mobile phone providers Kyivstar and Vodafone secured public wi-fi zones.

The first pensions were paid in cash in the first week after de-occupation as a result of cooperation between the Ministry of Reintegration and the Ukrainian Post Office. The latter opened its first two branches on the fourth day, and Nova Poshta – the leading private postal company in Ukraine – also opened an office. Oshchadbank and Privatbank – two biggest Ukrainian banks – re-opened branches in the first week. The head of the Ukrainian Railways visited Kherson on the second day after de-occupation; the railway connection to Kyiv was restored within ten days. Last but not least, the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky visited Kherson on the third day after de-occupation. Symbolically extremely important, these first steps demonstrated the ability of the state, civil society and business to cooperate in restoring Ukrainian sovereignty, rule of law and public order on the de-occupied territories.

It is difficult, however, to understate the challenges that Ukraine faces in the de-occupied territories in the mid-term. They include repairing the ruined infrastructure amidst continuous shelling; retrieving the deported Ukrainian citizens from Russia; documenting and investigating crimes committed by Russian against Ukrainian citizens; fighting poverty and providing social services, especially to the most vulnerable groups; and reversing Russia’s educational and symbolic politics.

Huge tasks also await in terms of transitional justice. The prosecution of collaborators remains a particularly sensitive issue. Lessons need to be learned from post-Euromaidan Ukraine, where police violence and the treachery of the local elites were punished too lightly and too late. On the other hand, the older generation still remembers the suspicion with which Soviet citizens who had lived under Nazi occupation were treated. It will be important, therefore, to proceed in a careful, generous manner, so that criminal liability does not exclude amnesty later on.

If the collective trauma is to be healed, transitional justice will also have to recognise and give voice to those who suffered, and to commemorate the victims. It should make reconciliation possible not only on the national, but also on the local level: the occupation has left society and local communities divided, torn by allegations of collaboration and mutual accusations.

There are reasons to hope that reconciliation and public dialogue in Ukrainian society will be easier than after 2014. Today, the country is united as never before in face of the common enemy. But the re-integration of the territories occupied in 2014 will be a more serious challenge. This will require a longer transition period, and probably international mediation.

This article was written within the framework of the Cluster of Excellence ‘Contestations of the Liberal Script’ (SCRIPTS). A earlier version was published in German in September 2022 in Osteuropa 6–8/2022.

The Taurian Governorate was a territorial unit of the Russian Empire between 1802 and the October Revolution. It included Crimea and the coastal areas stretching from the Dnieper in the west and north to Berdyansk in the east. This roughly corresponds to the parts of the Ukrainian regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia currently reoccupied by Russia. In April 2022, the Duma deputy for Crimea, Mikhail Sheremet, demanded that this governorate be restored by annexing the occupied coastal areas of the Azov Sea to Crimea.

Published 17 January 2023

Original in German

Translated by

Edward Maltby

First published by Osteuropa (German version); Eurozine (updated English version)

Contributed by Osteuropa © Tatiana Zhurzhenko / Osteuropa / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?

Mineral rush

Topical: Critical raw materials

Why does peace in Ukraine hang on a ‘mineral deal’ whose handling is more reminiscent of trade than negotiations? Perhaps because the global race for critical raw material mining is well and truly underway, digging for today’s equivalent of gold: raw earth elements and lithium critical for renewables and digital technology but also modern weaponry.