While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.

An Albanian girl is caught between the patriarchal cruelty of village life and the communist assault on traditional values. She flees to Tuzla in Bosnia, in the hope of finding the freedom to live as a woman denied her by the custom of “sworn virginity”.

We’re in Tuzla, the man says, that’s what wakes me, and then he lifts the corner of the tarpaulin off me. He’s not the man with whom I set off, his voice like a cornrake, raspy, he’s practically syncopating from hoarseness, but he keeps his face hidden. I couldn’t have slept that long, we can’t have reached Tuzla, it’s almost out of the question. I see only the sky from under the truck’s tarpaulin, a steely, sudden twilight, the kind that falls only in the highlands, no, we can’t have reached Tuzla yet. Deprived of sleep, I wandered among the rocks for two days, terrified of the armed men in my tracks, the echo re-echoing their shouts, making it even more frightening, and I was terrified of the mountain animals, too, especially the rock rats, because if you fall asleep, they suck your blood, and also of the nocturnal animals that I’d never seen with my own eyes, but had heard about from the villagers ever since I was a child; they carry off girls wandering off on their own, work them over, steal their soul, and then the girl stops being a girl and becomes an animal herself and has no place among normal human beings anymore. And during the day I was afraid of the snakes that sneak up on you, slithering from between the rocks, even the old people of the mountains have no antidotes for their venom, and even the innocent salamanders startled me if I didn’t recognize them right away. Every little sound startled me, even in the cave where I hid myself, and which I’d lighted on much earlier, I used to go there to read when I wanted to hide myself from the eyes of the world, whereas I was supposed to be collecting herbs, shepherd’s purse and devil’s nettle, my mother used them to make tea for women’s troubles for herself and for the rest of the women in the neighbourhood, and also for those girls who’d grown old enough for such troubles, and also manna and carline thistle, which served as sweets for the children of the mountains. This cave-like recess did me good service when I was fleeing, people couldn’t have known about it, it seems, because otherwise they’d have found me soon enough – the wind had carved a cavity behind a big rock face with just enough room for a girl like me to find refuge.

We couldn’t be in Tuzla yet, I knew it only from books, it was the only city I had any appreciable knowledge of, and I knew that it’s in Bosnia hundreds of kilometres from where I was, regardless of which route one takes, it says so in the book. I strain and pull aside the heavy, wet tarpaulin covering the back of the truck, it smells of urine or something very much like it, a sharp pungent smell, though the truck is used only for carting potatoes. Now it’s just me, though; they must’ve unloaded the potatoes some time before in the villages of the highlands where nothing of the sort will grow, but the couple of pieces that rolled back and forth on the loading platform where I was hiding would have given away the nature of the shipment in any case. As soon as we set off I bit into one, and though I couldn’t taste anything but the dirt, hunger is a great lord, and I wolfed it down, and then I fell into a deep sleep where they couldn’t reach me and couldn’t hurt me; as they rolled up against me I felt nothing, even though up here in the mountains there are many bends in the road that girds around the mountains as they dictate, and anything that’s not stationery gets tossed about on the slow-moving, bumpy truck.

When I emerged from among the bare crags, roughed out, smeared with blood, because my arms and legs and even my face were bruised, because sometimes I had to come sliding down the hollows washed away by rain on my backside for want of a proper path – this was up where the caps of the ridges meet, on the small, sharp stones that neither wind nor rain could rub smooth in a hundred years – when by some miracle I found myself on the rocky road that wound itself around the mountain like a ribbon, on one side the barren rock face, on the other a sharp drop, and this vegetable truck was the only vehicle to appear on the horizon for half the day, and I’d been standing under the scorching sun since morning, thirsty and at the mercy of the highlands, but up there, so close to the peaks, where sometimes we don’t hear the grumble of a single motorcar for days, even that was a miracle.

I gave the truck driver the ruby that my mother had hidden away when I was born, at least, that’s how she told it, hoping she’d have it set in gold once she managed to save up a bit of money of her own, and I’d wear it round my neck as an adornment when I grew into a woman, or at least until I give birth to a male child, she said, because around our parts a woman has no honour unless she bears a son. My mother couldn’t bear one; she had three girls, after which she prayed in secret, because even back then prayer was a forbidden activity where I lived, but to no avail, her womb would not conceive anymore, even though she wore that ruby sewn inside the border of her shawl. And I gave the driver this magic ruby that produces a male child; I secretly took it from my mother’s shawl on the night of my flight; I cut it out of the muslin, just like I’d cut them, my family, from inside of me; I tossed all memories of them from me like a stone, though with the memories a bit of softness was gone, too.

That ruby wasn’t much use, but the driver couldn’t have known that, he took it and in exchange promised that under the truck’s tarpaulin he’d help me escape the place of my birth. He knew what he was risking, because everybody knows the Kanun, even those who are strangers to the region, he knew he was crossing the Accursed Mountain, where the men folk even herd sheep with a gun slung over their shoulder, and if they catch us together on the way, they will kill him too in accord with the laws of blood feud, there’s no mercy, and for all he knows, by helping me escape he could be bringing trouble not just on his own head, but his entire clan too. He fell in love with that stone, I could tell right away, and also that he’s feeling sorry for me standing there with my cropped hair, a pair of tattered cloth pants, a man’s shirt and a once burgundy velvet vest, which hides my newly budding breasts all the same, and also a watch chain hanging from my vest pocket, just like on the clothes of the men in our parts, where a watch is never attached to the chain, it’s only for show, because up there, in the snow-clad mountains of the north, on the summits of the Accursed Mountains where the sky is just an arm’s reach away, time has come to a standstill, and measuring it would be futile, and my people don’t like waste, and so I didn’t waste my words either, I just asked the man to take me with him in exchange for the ruby, and he nodded his assent. He must have come from the south, yet not a muscle on his face stirred, all he said was, just be careful, then he pulled back the filthy, foul smelling tarpaulin and shoved an old coat under me that must’ve served as a bed for his dog, because it was full of white hairs, and also, despite my men’s clothes, he must’ve seen that I was a girl, whereas in our parts girls always go about in shawls, their hair hardly showing, lest strange men take a fancy to them. I’m headed for Tuzla is all I said, and he said he’s headed that way himself. That’s all there was, then I fell asleep even before he revved the motor.

I climb off the truck and take a good look at the man with the raspy voice, for the time being only from behind, a big hefty fellow with a slight hump sitting on a rock, ravenously gorging himself, when I call to him he wipes his lips on his arm, but he doesn’t turn around, he’s not my driver, the one with whom I’d reached an understanding, I can see it from where I am, he doesn’t need to turn around, mine was skinny with an honest bearing, while a man with a hump always has an air of guile about him. I can sense that I’m in danger, we’re nowhere near Tuzla, we’ve hardly left the mountains, I can still see the snowy peaks, the wild pattern of protrusions that make you dizzy unless you were born in the highlands, they have hardly retreated, there are hardly any slopes yet to be seen, or pebbles, though there’s grass, a sort of pasture, I see sheep, but no shepherd, the sheep are leisurely drinking by the stream, barely moving white spots on the landscape. A bit further off, as if to enrich the hilly scape of the Alpine surroundings, Enver Hodza’s concrete bunkers bulge their backs all around, now that the new regime allows, the mountain people paint flowers and all sorts of colourful trailers on them, and also imaginary animals to disguise their reality, but even with the flowers they’re still bunkers, bulging out of the earth, threatening, in unison with the man’s back, I’m thinking, a scary still-life; on the other hand, at a great distance, on the horizon, I can already see silvery smoke, smokestacks in the twilight. But here we’re still hidden by the dark of the pines and the crags, we’re nowhere near Tuzla, this is still my land, I realize with a start, and I don’t understand what’s become of the other driver, I call to the man with the raspy voice, but I don’t know his name, not that I knew the name of the other man either, but I could see the concern in his eyes, that he’s a good man, while this one is sitting with his back to me with no intention of turning around, not that I have anything left to give him, that ruby having been my only possession. Run, I’m thinking, and my muscles respond to the command, but as soon as the branches snap and the stones grate under my feet, the humpback grabs after me like a wolf, pulls me down by the ankle with all his might, and suddenly the landscape turns upside down with me as I fall onto the sparse grass and he on top of me, helpless like a sack of potatoes, breathing down my neck, disgusting, his saliva drooling all over me, I hit my head, the pain makes me review my life, I see pictures, except there’s no countdown, just the rush of fear rolling the memories past the periphery of consciousness, and the rocks jeering, echoing my groans.

*

The rocks toss my groans back and forth, toying with them until, having torn the sounds to shreds, they swallow it up for good. I have no accomplice anywhere in the surrounding landscape, the moss-grown sides of the tree trunks just deaden the noise; besides, nobody ever comes this way, there’s nothing but the indolent bleating of the sheep, with not a thought to me. There I go whining and whimpering again, my father would say and would slap me so as to give me good reason to cry. Because you shouldn’t cry for no reason. I should have been born a boy, at least, that’s what my father would have liked, he was angry with me, I think, for not being born a boy. My two older sisters had been married off when they were still children; as a matter of fact, Lule, who was the oldest, was given in marriage while she was still in my mother’s womb – provided, of course, that it was going to be a girl, and also, not until she had reached sixteen; but my father was hoping all along that it’d be a boy, and each time it turned out that my mother’s womb had unloaded yet another girl, my father would beat her; a girl to swell the rank of servants, as he put it, and because of whom his possessions would be divided among the clan, who’d even carry his fence off, stone by stone. Because the clan needs male children. According to the laws of my people a girl child can’t inherit, she has no right to possessions, if there is no male child in the family, sooner or later the estate gets divided up among the other families of the clan – the land, the animals, the women. In accordance with the Kanun, a family without a man is doomed to extinction. Still, there is a way out, the clan can elect a girl to be its future head, a girl who, from that moment on, must live as a man, she must wear men’s clothes, have her hair cut short like a man, and must adopt a bearing very different from her humble girl companions; also, she must never come to know love, either first hand or otherwise, neither as a man nor as a woman. But by way of compensation she can play dice and tavli with the men in the tavern, she can drink with the men, but they never ask for her opinion, for she’s just a woman, after all, even if she’s got a gun slung over her shoulder, a woman whose been saved from servitude, but also from the ecstasy of physical love. Because those thus elected must take an oath of virginity and can never know the touch of a man unless, of course, we consider the practice of the blood feud a kind of touching, because the sworn virgin, or virgjinesha, as my people call these women turned into men, must not only head the clan after their fathers have grown too old, not only must they make decisions and manage the estate, they must also exact vengeance if need be, just like a man – after all, the virgjinesha is the head of the family now, while the blood feud, or gjakmarrje, as we call it, is practically an everyday occurrence in the highlands that was my birthplace. The intricate laws of the Kanun have strict rules about what you can and cannot do. If someone’s family suffers a grievance of any sort, the Kanun specifies not only the manner of the assassination to which the man chosen by the family to carry out the killing is bound, but also the manner in which the fatal weapon should be left by the victim’s side, so his family should know right away that he’s been the victim of a blood feud and not of chance, which will give them more time to prepare their counter-feud. The Kanun even makes attendance at the dead man’s funeral compulsory, and mourning, too, all this in the greatest possible detail, of course – the wake, the rent clothes, the scratched faces, the amount of ashes to be sprinkled on the head; it specifies everything down to the last drop of blood, after which everything begins all over again, the killing goes on and on, so that just hearing about it fills a woman’s heart with dread and loathing.

Still, my father decided that I’d be a virgjinesha, in secret and against my mother’s wishes, for a woman’s words are of little avail in the clan, so she never dared to say outright what was in her heart, and my father made me wear boys’ clothes from an early age and kept talking about this sworn virgin thing, and what a boon it was, a way for me to break out of a woman’s servitude, and I don’t have to become the property of a man and his family, and though a woman, I can decide about my own life. I say in secret, because by then the government was dead set against sworn virginity and the Kanun in general, along with everything that was its consequence, the blood feuds, the curses, and surprisingly, even folk embroidery, which was passed down to us from our great-grandmothers and made what was good in life more colourful, because all this was the vestige of the old, hostile regime, and instead of standing for equality, it stood for the power of one man over another. But my father was a great subversive, he spent practically all his time engaging in blood feuds and playing tavli and dice, though he also worked very hard, of course; he vilified the regime, and even prayed now and then, though that was also prohibited; the communists had exiled God from my native land to some far-off place, and yet, He occasionally found us up there, among the peaks. But prayer did not prevent my father from beating the family to a pulp now and then, the four women sent by fate to try him, as he used to grieve in his drunken sorrow.

I am thinking about them in the past tense because I’ve excised them from within me, my father, whose slaps I will never forget and who, being a man of extremes, was either beating his family or, suffering from pangs of conscience in consequence, tried to appease the Lord, showing Him sacrifices so his terrible sins should win forgiveness; and in order to make the sacrifice, he took the food out of the mouths of his family, with mercy towards none – my mother, who was quiet, of slight stature and eyes like a doe, deserving of her servitude; my older sisters, whom I never got to know as well, for being a late child, by the time I could comprehend, they’d been married off long since, but they didn’t give birth to male children either; and so, because of this, people in the village started whispering that the clan of the Larikala is cursed, and given time, will disappear off the face of the earth – the time that my people never minded in the short run. Lule and Pashke became no better than servants at the homes of their husband’s parents, they worked day and night, washed the feet of the male guests; we saw them only occasionally, during a holiday when the entire clan gathered, or at the funeral of a victim of the family’s blood feud, where attendance was compulsory and so was mourning the dead man, who was almost always in the prime of life, and whose death heralded the beginning of yet another blood feud, which is how the Accursed Mountains got its name, and because of which the men folk of my native land were slowly nearing extinction.

And so my mother had more time for me when I was a young girl; she taught me the ancient embroidery stitches, the elaborate, meandering hoops she’d learned from her grandmother and with whose help you could embroider things of great beauty onto bare cloth – silk, muslin, we even embroidered cashmere in the evening – we hummed lullabies for male children in the meanwhile, while my father discussed the usual male matters at the tavern and kept slapping the knife into the table top with great vehemence. I gradually learned how to embroider and sew. We worked by the light of a single lamp lest anyone see us if they looked through the window, because they might take us all away and question us, asking if we believed in communism. You can’t take Enver Hodza for a ride, but you can outwit him, my father used to say, and as for you, girl, you’re going to be a virgjinesha, because my father’s fortune isn’t going to be divided up amongst the clan. You’re our only hope, he said.

At first I didn’t know what it meant to be a sworn virgin, I realized it only by degrees after I was already going around in men’s clothes, and after everybody in the village already knew that I’d never become a woman. They talked to me like a man, and about me, too, and when I was sworn in, my name was changed from Dardana to Dardan; even my mother couldn’t call me Dana except in secret, when we were alone. At home I had to practice my new bearing, I had to hold my head as if my neck had suddenly gained in girth, as if I had to face some fearful unruly bull at any moment, and on the first day I was even given a pack of cigarettes to go with the raki, which I had to swallow in one gulp, all of it, the first occasion in my life when I drank raki, a girl, after all, doesn’t drink hard liqueur, and as soon as I drank it, it made my insides churl as if I’d swallowed tongues of flame; I couldn’t breath for minutes on end, or so it seemed to me, while the men in the tavern screamed with laughter, and I had to ran outside to the fence, and tried to recover with tears in my eyes and tried to vomit, but couldn’t.

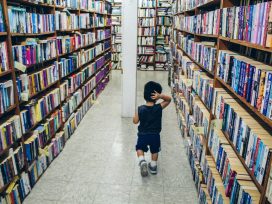

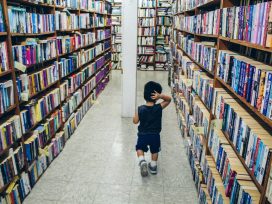

Later, I got used to the cigarettes, but the raki and the weight of the gun on my shoulder never, and a lot of other things neither that came with this virginity, because I was gradually broken in to do men’s work, I cleared the rocks from the little arable land that my family had with a pickaxe and dragged them up to our house for a fence, arranging them into a tight, regular heap, as if I were building a bulwark at the very least, because it was the way of my people to take precautions against possible threats, and I also ploughed the soil with a mule and crushed the corn and harvested the dry stalk for winter, to feed the animals. Still, having to give up a woman’s fate meant a freedom of sorts, though this freedom was not elected, my father doled it out to me. On the other hand, I soon got used to the good things, because it was good that on Sunday I could read in public, in fact, whenever the fancy took me, in front of everybody, and even on weekday evenings when it was getting dark and I couldn’t work, any time, practically, even when the women had to withdraw into the inner room; besides, women belong in the kitchen, or maybe around the children, but a woman can’t play the wise man with a book in her hand, it’s enough if she learns her alphabet in the village school. There was a book on Tuzla, I found it in a gap in a wall of the hayloft, a long time ago somebody must have used it to stuff the crevice, to keep the fodder from getting wet, it was an old book smelling of dust, it had gotten wet repeatedly, it was mildewed, but I read it with great pleasure, it taught me how to read really well, and also all those many geographical expressions and names, and so Tuzla became the only city I ever knew, since we never travelled, because where I was born, you weren’t allowed to travel, unless we count as travel the time that my father was in a good mood and took the family to the Bayram at Koplik; we had no business there, because in our parts everybody’s Catholic, but there was a country fair and many beautiful things in the bazaar, and a girl child loves finery even if she’s very young and has seen little of the world. But I also read other things ravenously that my father kept at home, the papers, for instance, which he held in great regard, because they reached us up in the mountains only at rare intervals. Because of Enver Hodza’s informers, we read the Bible only in secret, and so I knew fewer prayers than maledictions.

Sometimes I would read in the evening, but sometimes my mother and I would do our embroidery, in secret, because it wasn’t fitting for me to engage in girlish pursuits any more; it was, in fact, practically forbidden, and at times, including the times when this came to light, both of us bore the brunt of my father’s anger, absorbing the shock waves of his rage. Some silken thread remained from my maternal great-grandmother, and we dyed it with the berries of the purple smokebush, whatever the vermin didn’t consume, that is, and also with gentian. We got beautiful colours that only nature could better, and at such times I could be Dana again for a while, even if only in front of my mother and myself. And then, once I sewed myself a piece of women’s underwear in great secret, I embroidered it all around with gentian flowers and ladybells, using the beautifully dyed silken threads, a pair of women’s drawers I’d copied from a newspaper that had found its way up the mountains, God only knows when, among people not the least refined, to a place where women are not accustomed to underwear. For some reason I coveted a really feminine piece such as this more than anything, sworn virgin or not, I needed to feel the silk rub against my skin, the mere thought of which calmed my mind, knowing that under the men’s clothing I would be wearing a pair of silken drawers just like the genteel girls in the big towns, or even in Tuzla, and which, on top of everything else, is adorned with embroidery that was taboo now throughout the country. I had almost finished embroidering the gentians on the lower section that covers the thighs when on a whim I tried it on; there was nobody around, my mother had long since gone to bed, my father was probably playing tavli in the tavern, and talking politics. The silk was cooler and smoother that I could have ever imagined. The black hair of my secret womanhood showed through slightly, because although I was young, a girl child matures quickly in our part of the world, but the drawers made a beautiful fit, neither too tight or too baggy, they felt just right, and such a wisp of a material would also fit under my man’s pants without anyone being the wiser. The sole mirror hung on the door of the big wardrobe, I had to go to the clean room, I had to take a look and see what I’d be like as a woman. I got absorbed in that image of myself and was thinking how happy a man would be, any man, if he could see me now, when suddenly, in the halflight of the room, the figure of my father loomed over me. For a split second we locked horns, his eyes seemed to be shooting flashes of lightning, then I drew my eyes from his, lowered them like somebody who has just committed a heinous sin, and began praying in silence, saying the prayer my mother had taught me when I was a child for those occasions when I was afraid of the dark. My father bounded over to me, ripped the silk pants off of me, though I tried to avoid his grasp; with a quick motion he tore off one side, while the other lay against my left thigh with the gentians, and in the meantime the black between my legs was revealed; I covered it with both hands to hide it, but had no time to feel the mortification because my father’s drunken fingers were feeling me up by then, like someone who can’t resist the miracle and will touch it even if he must turn to a pillar of salt because of it. I tried to repell him, but he struck me repeatedly, then threw me to the floor of the clean room, on the rug we weren’t allowed to walk on with our shoes, not even as children, and then he was on top of me, panting, his breath smelling of wort, and he whispered, though it sounded more like a scream, I’m going to show you what you must never know, ever, because you will never be a woman, but I’m going to show you anyway just this once what it’s like being a woman, because I am a good father to you. I didn’t yell, because I was scared; besides, I knew that if I made a racket he’d strike me, I grit my teeth and kept my eyes peeled on the cobweb in the corner, as much of it, anyway, as I could see from where I was on the rug, and I put up with the pain that came with the thrusts of the man who was, after all, my father. The spider continued to weave its web in the corner as if nothing had happened, and my father must have made a lot of noise, but none of it reached me, only the pain beckoned from some far off place, time came to a standstill, and as he rocked himself on top of me, groaning, straining, yet rhythmically, the mirrored door of the wardrobe swung to and fro, and then I saw my mother in the mirror, in her nightgown, without her shawl this time, her hair disheveled, at times she appeared, at others disappeared, as if she were only half there and could only half see what my father was teaching me, and then I wasn’t looking at the spider anymore, I was looking at my mother’s face, her face changed with every slight motion of the mirror, showing surprise, despair, helplessness, anger, jealousy, hate, and then I didn’t see her there anymore, she’d gone back to bed without having said a single word, in fact, and then I never saw her again, because that very night I made my escape.

*

His groans brought me back to reality, his raspy groans, the big, sack-like man is lying on top of me, with all his weight, a sticky catchfly swaying in front of my eyes, gently scraping against the bruises on my cheek, as he’s having his will of me, I can’t see his face properly from below, just that his beard is turning gray and it’s dirty, his eyes dark as pits, like some animal’s, but I don’t want to see him anymore, I know he’s not my driver, the one I gave the ruby to, not that it makes a difference now; I smell the stink of garlic and a pungent man’s sweat, he’s gripping my short hair with one hand, with the other he’s trying to pry my thighs loose, trying to enter me against my will in the place where it’s already hurting, and all around the barren cliffs, the scattered pines, the sound of the dogs’ bells as they herd the sheep now at a distance, but possibly there were no sheep, just the white light of the cliffs piercing the dark pasture, and only the murmur that is specific to great mountains could bear me witness, the rumble that is suddenly splitting my ears. I’m practically outroaring the Accursed Mountains themselves by now, but to no avail, there is no one around, night has fallen, and the man’s put a rough hand over my mouth besides, my teeth tear into my cheeks inside, and by then I stop praying, because there’s no prayer that could put a stop to this, God is too far away, the path of my prayers too distant to reach Him even though we’re in the mountains, close to His skies, and my eyes shower him with my curses, every part of me, every pore, my way of repelling him, and that great big sack-load of a humpback suddenly releases me, but no, he doesn’t release me, he jettisons himself off me, pitching himself off my tormented body like one struck by lightning, his arms and legs go stiff, he flings his head back, his neck strangely taut, his body convulsed, the like of which I’d never seen before, his eyes rolling, his tongue rolling, the saliva drooling at the corner of his mouth, which makes me even more frightened than before, because curses seem mightier than prayers, and I’m running, just barely grabbing my clothes, yet after a couple of steps I stop, quickly look around for a branch and go back to him, mesmerized by this St. Vitus dance, then I pull myself together and shove the branch between his lips so he won’t swallow his tongue, and so as to make room in the world for my future prayers. The potato sack body slowly relaxes, but the humpback hasn’t quite recovered yet, and suddenly he makes me think of my father drunkenly panting on the expensive rug of the clean room that night, an imbecilic, roguish smile under his moustache, and not understanding what he’s done, my father, whose half-naked body I’d written full of black ink just three days hence, the night I set off, I wrote it full of all the Albanian curses there are, covering the sleeping body of my father with the claspers of my hate, to grow there for ever more, I wrote his body full of the desperate striving to excise from inside me the memory of the two-headed black eagle, even, and also the dogged determination that would take me to Tuzla, where I would be Dana Larikala, a respected woman and free, and never again a sworn virgin.

Published 19 February 2010

Original in Hungarian

Translated by

Judith Sollosy

First published by Magyar Lettre Internationale 75 (2009)

Contributed by Magyar Lettre Internationale © Kinga Kali, Judith Sollosy / Magyar Lettre Internationale / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.

Being diagnosed with ADHD can be a relief for those who have struggled long and hard to adopt constraining social norms. For neurodivergent women, masking can lead to poor mental health, substance abuse and hyper-sexuality. Vox Feminae takes a first-hand dive into positive coping mechanisms for the inattentive and/or hyperactive.