The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Generations of Russians schooled during and after the Soviet Union were taught that Russia’s imperial expansion took place peacefully. In this version of history, Russia was always reacting to western aggression. Sound familiar?

When we were in Soviet school in Moscow in the 1980s, the real treasure that passed from one kid to another were the Tomek books. It was classic teenage literature about a boy who travels around the world having adventures while hunting for wild animals. The stories took us to Australia, Africa, South America and were thrilling to read because they made us acutely aware of a very tiny chance of visiting the places they described.

The first in the series was Tomek in the Land of the Kangaroos. It opens with a scene set not in Australia, but a school in Warsaw, where the kids in a class are talking about their much-hated teacher. And then it is revealed that the year is 1902, that the children are Polish, and that the teacher is a Russian drunkard recently sent to the school to Russify them, prohibiting them from speaking Polish and eradicating Polish national feelings. Tomek, the son of a Polish revolutionary in exile, is a particular target of the teacher’s attacks, but he is a smart boy and always finds a way to fight back.

A few pages later, after another joke he plays on the teacher, Tomek goes home. Waiting for him there is a stranger, a friend of his father. He offers to bring Tomek to his father, so that he can join him on an exciting adventure: a journey to Australia to capture wild animals for a zoo in Germany. Tomek agrees and that is when the real story begins.

In our Soviet childhood we had plenty of books about the revolutionaries and their brave fight against the Tsar. But the Tomek books were the one of the very few which told a slightly different story about the Tsarist regime – that it was not only oppressive, but also imperialistic.

In Soviet schools the Tsarist regime was presented as the most oppressive and backward regime in Europe. But somehow the imperialistic nature of the Russian state was not stressed in the historical narrative. In universities it became a bit more complicated, but not everyone went there.

Take Peter the Great. He was always portrayed as a positive historical figure in our schoolbooks. As a modernizer he hacked a window through to Europe, to cite the great Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin. He did so by building up St Petersburg, but not before taking over the Baltics from the Swedes. We were never told how the local population felt about this. It was a glorious deed by a great tsar who set Russia on a new European path.

The reason provided in our schoolbooks for all of this was very simple: Russia ‘needed’ access to the Baltic Sea, just as it also ‘needed’ access to the Black Sea. Otherwise, it would have languished forever in obscurity. What the cost of this ‘need’ was, and whether other nations and countries had ‘needs’ of their own, was beyond the scope of history lessons.

Russia’s dramatic territorial expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries was discussed in Russian schools. The official narrative was that the Russian empire was the only empire built by peaceful means – and that other nations just wanted to join it. The two examples the Russian schools provided were Georgia and Ukraine.

Ukraine, the Russian schoolbooks assured us, became part of Russia when hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky, the leader of the Cossack revolt against Polish rule, asked Tsar Alexey for patronage and protection. The reason was that the Poles, being Catholics, were repressing the Cossacks, who were of the Orthodox faith. In 1654, a Russian ambassador went to the Ukrainian city of Pereyaslavl and the two parties signed a unity treaty. The real history of annexation of Ukraine was of course much more complicated: Russia incorporated the territory of present-day Ukraine only after a series of partitions of Poland and the conquest of Crimea.

In Georgia’s case, the term used was ‘joining the Russian Empire’. According to the official version, in 1801 the Russian emperor Paul I, supposedly executing the last will of the dead Georgian king Georgi XII, signed a Manifesto of Accession of Georgia. The real story was different: when Giorgi died on 28 December 1800, the kingdom was torn between the claims of two rival heirs. The Russian emperor wanted neither, so he decided that the monarchy be abolished, and Georgia be administered by Russia. The Georgian envoy in St Petersburg reacted with a note of protest, but to no avail. In May 1801, Russian troops removed the Georgian heir to the throne and installed a government headed by a Russian general.

Out of this very selective history, a remarkable narrative emerged: that Russia was never on the offensive. On the contrary, the country was always under attack, defending itself from the east and, more importantly, from the west.

Take the most dramatic episode in Russian medieval history: the Mongol invasion. At the most sensitive moment in the battle, the Crusaders invaded the medieval Rus. The West had stabbed Russia in the back, according to the schoolbooks. To the rescue came Alexander Nevsky, the legendary Russian prince, who defeated the Swedes and Germans in 1242 in the Battle of the Ice. The West launched the Crusades in the Middle East, so the moral of the story, but was defeated when it tried the same against Russia.

The reality was less glorious and more complicated: Nevsky, a local warlord, was hired by the merchant Republic of Novgorod to protect its interests in the Baltics against the Swedes and the Teutonic Order. There were Catholic Crusades in the area, but they were directed against the pagans occupying the territory, whom the missionaries considered a legitimate target, and not against Russia. The Novgorodians were also trying to convert Estonians.

Nevsky has always provided a good opportunity to recall western imperialism. He was sanctified by the Russian tsars and – under Stalin’s orders – was made the subject of an eponymous film by Sergei Eisenstein. In the official history of imperialism, the Russians always come out on the opposite side. This has led the Russians to have a curious perception of themselves. Despite being empire builders, they feel that they have been the target of a series of colonization campaigns by western powers.

Still from Sergei Eisenstein’s 1938 film ‘Alexander Nevsky’. Source: Wikimedia Commons

But the Nevsky story is key in the Russian narrative for another reason too. Apparently, the Teutonic Order’s crusade against Novgorod was much worse than the Crusades, because the Russians were Christians, just like the Germans. This apparently shows that the West has always been treacherous and used ideology to attack Russia. The Nevsky myth helped to entrench the unique position held by the Russian Orthodox Church in Russian society.

The Russian Church has historically been closely connected with the state. The Russian Tsar was the head of the Church and Russia’s brand of Orthodoxy is based on the belief that Moscow is ‘the Third Rome’ (after ancient Rome and Constantinople). Being ‘unique’, Russia sees itself as surrounded by enemies. The Russian Orthodox Church is always suspicious of Catholic expansion, the Nevsky episode serving as a perfect proof.

This mentality has direct implications for today. Just two years after Putin came to power, five Catholic priests were expelled by the FSB from Russia. Some were accused of espionage, but their real ‘crime’ was proselytizing. Similar fears explain why John Paul II was never let into Russia, despite his numerous requests: the Moscow Patriarchate feared his visit could undermine its hold on the territory it believed to be ‘theirs’.

When we were taught history, the 19th-century was dominated by two grand narratives: first, the Napoleonic invasion and the Decembrists’ failed but glorious revolt; second, the emergence of the revolutionary movement in the second part of the century. The long and terrible subjugation of the Caucasus was taught mostly through the works of Pushkin and Lermontov, both of whom were quite enthusiastic about Russia’s military exploits. Take Pushkin’s ‘A Prisoner of the Caucasus’:

And then I shall celebrate the glorious time

when our two-headed eagle, scenting bloody combat,rose up high against the disaffected Caucasus,

when the roar of battle and the thunder of Russian drumsfirst broke out along the foam-flecked River Terek.1

According to the official version, the huge territory beyond the Urals – Siberia – was populated mostly by savages and barbarians, so its annexation did not qualify as a proper invasion. Russian authors and artists were not really interested in this story. The true symbol of this land became the katorga, a system of harsh penal labour invented by the tsars. Siberia became such a horrific place for prisoners and exiles that it had a curious psychological effect on Russian society: people avoided talking about Siberia at all costs.

The word used in Russian schools for the colonization of Siberia is ‘subjugation’. It is the only time that official history admits the subjugation of any territory. But even here, it is Siberia’s harsh and brutal nature of that was subjugated, and not the many indigenous peoples that populated it.

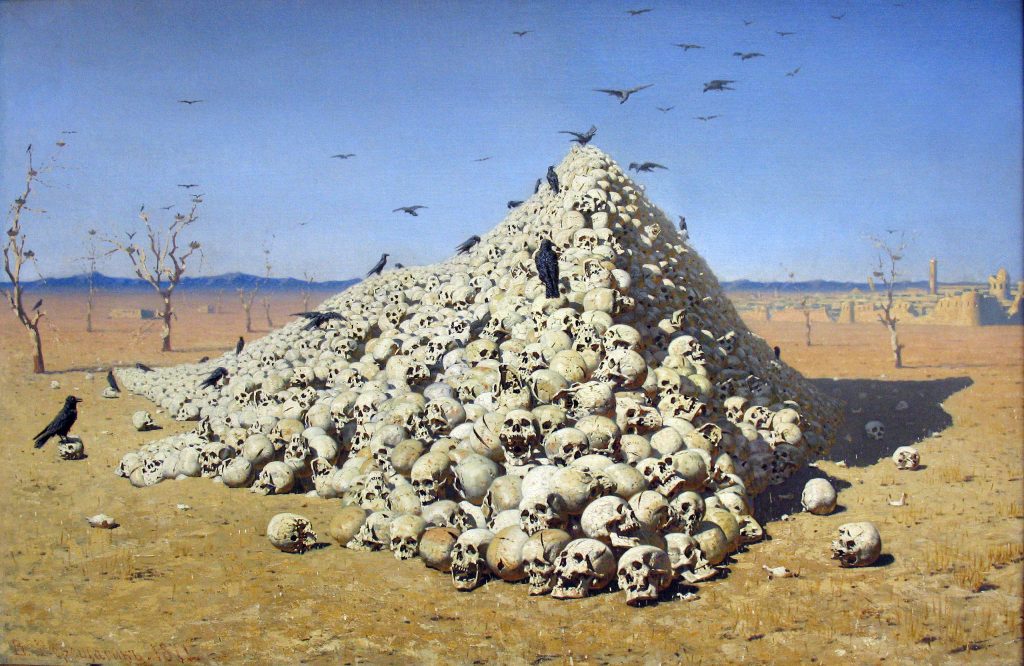

The bloody conquest of Central Asia was also misrepresented, if not ignored entirely. The Russian artist Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904) was embedded with the Russian troops in their conquest of Central Asia. In 1871 he painted ‘The Apotheosis of War’, one of the most famous anti-war paintings in world history, depicting a pile of skulls outside the walls of an Asian city. The painting was dedicated ‘to all conquerors, past, present and to come’. Although the Russian conquest was indeed bloody and brutal, the skulls belonged not to the victims of Russian soldiers, but to the victims of the Asian despots like Timur. Instead of being a critique of the Russian invasion, the painting condemned oriental barbarity.

Vasily Vereshchagin, ‘Apotheosis of War’ (1871). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Where it was impossible to deny that Russian troops somehow found themselves very far from Russian territory, the Soviet schoolbooks blamed the tsars. The Napoleonic invasion was yet another proof that Russia was always defending itself against the West, in this case waging a glorious Patriotic War against the foreign attacker.

While Russian general Suvorov’s exploits in Italy a few years before were mentioned, his presence in Europe was blamed on Paul I, who had foolishly been honouring Russia’s obligations to its allies. This was the same Suvorov who, five years earlier, had massacred thousands of civilians in the Praga district of Warsaw while suppressing a Polish revolt led by Tadeusz Kościuszko. Of course, this was never brought up. If anyone raised the issue of Poland, Alexander Pushkin, ‘the sun of Russian poetry’ and the most popular author in the country, had the ready answer in his poem ‘To the slanderers of Russia’:

Why rave ye, babblers, so – ye lords of popular wonder?

Why such anathemas ’gainst Russia do you thunder?

What moves your idle rage? Is’t Poland’s fallen pride?

’T is but Slavonic kin among themselves contending,

An ancient household strife, oft judged but still unending,

A question which, be sure, you never can decide.

And closer to the end, Pushkin’s counterattack:

To you the Kreml and Prága’s tower

Are voiceless all, you mark the fate

And daring of the battle-hour

And understand us not, but hate.What stirs ye?

Is it that this nation,

On Moscow’s flaming walls, blood-slaked and ruin-quench’d,

Spurn’d back the insolent dictation

Of Him before whose nod ye blenched?’2

By ‘Him’, Pushkin meant Napoleon and his humiliating retreat from Moscow in 1812. The implication was that the western powers criticized Russia not because they cared about Poland, but because they envied Russia’s patriotism and ability to defeat the aggressor whom other European countries had failed to stop.

The same story was repeated time and again. It was the narrowminded Tsar Nicolas I who provoked the French and the English to attack ‘our’ Crimea in 1854, even if the Russian soldiers’ heroic defence of Sebastopol against the western attackers became an important part of the Russian narrative. And it was an incompetent Tsar Nicolas II who dragged the country into the First World War, again to honour his obligations to his allies. But then the Germans invaded and after the Revolution tried to annex Ukraine.

When there were no more tsars to blame, ‘needs’ came into play again: most manifestly, of course, in the official history of the Second World War. The Red Army invaded Finland and the Baltics because the Soviet Union ‘needed’ these territories to prepare against the upcoming German invasion. What happened next would officially be called the ‘Second Great Patriotic War’.

Generations of Russians have been raised with this narrative, and so it should come as no surprise that a great many people truly believe that NATO has been plotting against Russia for decades, drawing ever closer to the Russian borders, waiting for a good moment to attack.

NATO is simply doing what the German crusaders did in the 13th century – using the army and ideology (this time ‘liberal values’) to attack. This myth circulates constantly in Kremlin propaganda and was repeated by Putin in his infamous article ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, published on 12 July 2021.

Two months later, Putin opened a gigantic monument to Alexander Nevsky in the Pskov region. In his speech at the unveiling ceremony, he made a strikingly familiar claim: ‘Alexander Nevsky and his soldiers stood up mightily and impregnably to fight for what was the last frontier of the Fatherland.’ And on 20 February 2022, just four days before the re-invasion of Ukraine, Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stressed on the TVV channel Russia-1 that: ‘Russia has never attacked anyone throughout its history. And Russia, which has survived so many wars, is the last country in Europe that even wants to utter the word “war”.’

That statement might sound bizarre to a western audience, but not to the Russians, who have grown used to this historical narrative since their schooldays.

At first glance it is striking that the official history of the Russian empire was never seriously revised in the Soviet education system, unlike the domestic policies of the tsars. And of course, in our copies of the Tomek adventures, the fact was never mentioned that the author, Alfred Szklarski, was born in the United States as the son of a Polish émigré, that he returned to Poland after it became independent from Russia, took part in the Warsaw Uprising and spent several years in communist prison on charges of collaborating with the Germans.

The Soviet Union used the Internationale – the song composed by the Paris Communard Eugène Pottier – as its national anthem for twenty years. But the state was never truly international in its outlook. Stalin and his obsession with the Russian empire had a lot to do with this. After all, it was he who resurrected the myths of Suvorov and Nevsky – during the Second World War he created orders of merit named after both men to award his most able generals. And it was Stalin who promoted Peter the Great and Ivan the Terrible as ‘positive’ historical characters. But neo-Stalinism is only part of the answer for the persistence of the Russian victim narrative in contemporary Russia.

The same narrative about Russian imperial exploits persisted in schools after 1991. In university and academia, history looked a bit more complicated and some debates were allowed to take place. But it is the history taught at school that defines the national mentality. The school curriculum and the national literary canon: this combination creates the emotional and deeply entrenched perception of what is acceptable and noble, and what is not; the national pantheon of heroes and catalogue of villains.

That canon has proven to be truly stubborn. Recently the Kremlin tried to change the public perception of the Decembrist revolt as a conspiracy of terrorists. The propagandists were following a new trend of presenting every revolt in Russian history as an attack on national security, and thus as treason. But they failed miserably, mostly because the propagandists were unable to provide Russian schools with a substitute for Lermontov and Pushkin, one that would praise the tsar instead of the Decembrists.

But it also means that where Pushkin and Lermontov speak as Russian imperialists, that too stays in the national consciousness. The invasion of Ukraine clearly shows that something must be done in Russia to break the tradition of historical falsification in the school textbooks. Only then will future generations of Russians be able to see a different past – the necessary condition for building a different future.

http://faculty.washington.edu/jdwest/russ430/prisoner.pdf

https://russianuniverse.org/2014/09/24/slanderers-of-russia/

Published 4 December 2022

Original in English

First published by Wespennest 183 (2022) (German version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Wespennest © Irina Borogan / Andrei Soldatov / Wespennest / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?