On the Cape of Tarkhankut on the western shores of Crimea lies an underwater ‘graveyard’ of statues from the Soviet past. The museum is a metaphor for how cultural memories are formed in a shared unconscious traumatized by loss and unable to adjust to the new order of things, writes Ilya Kalinin.

The message left to future generations by Plato’s myth of Atlantis is not that in the depths of antiquity there existed a civilization of unparalleled greatness, but that it disappeared underwater. One of the most important directions in the poetic imagination is thereby defined: dreams of another realm, but not ‘heaven’ in any classic sense. The space for this alternative social order became either the far seas or the bottom of the ocean. The historiosophical semantics of the Plato of the Timaeus and the Critias bring the catastrophe of the loss together with the mythology of the model preserved forever at the bottom of the sea; here, the ruins are an image freed from its former perfection.

For it to remain in cultural memory, Atlantis had to be destroyed and disappeared from the surface of the earth. Its unseen remains gain their utopian power precisely because they are hidden from view and became one of the basic topoi of an alternative social imaginary. Atlantis had to disappear underwater to appear on the horizon of history; it had to fall out of history and evade the circulation of ideas, epochs, and formations, becoming an invisible, submerged conceptual shell setting the space for a socio-cultural alternative.

The ‘oceanic feeling’

The element of water is one way of embodying the idea of time in its paradoxical clash of immutability and movement. However, only one of the motifs associated with water interests me here. Its origins are relatively recent in nature, though indebted to the ancients. This is Romain Rolland’s ‘oceanic feeling’, used in his letter to Sigmund Freud, in which he put forward his view of the origins of religious feelings. This letter was the answer to Freud’s The Future of an Illusion, which addressed this very problem. Rolland, who combined a sympathy for Bolshevik Russia with an interest in the Vedas and yoga, described oceanic feeling as transcending the limits of the time-and-space bounded personal ego – as a person’s fundamental ability to experience the sense of timeless oneness with the world.

Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents tried to answer Rolland by widening the scope of the problems under discussion, going from the origins of religion to a diagnosis of the modern human condition. Freud claims the human ego ‘splits’ due to the competing demands of the id and the super ego. Unconscious desires collide with the imperative of culture; the pleasure principle collides with the reality principle; the libido collides with civilization.

Freud’s disappointing conclusion was that the dramatic triple conflict between ego, id, and super ego, fundamental to the human psyche and its basic drives, only increases in the modern age. Freud tried to discover the aetiology of oceanic feeling, finding it in the early stage of the development of the ego, in which it has not yet differentiated itself from the outside world. In this way, infinity and a feeling of being one with the world, typical of Rolland’s oceanic feeling, was identified by Freud as ‘infantile narcissism’.

Freud uses an archaeological metaphor, comparing the psyche of an individual with the cultural layers formed through the ages and built up one on top of another: ‘nothing once formed in the mind could ever perish, that everything survives in some way or other, and is capable under certain conditions of being brought to light again’1.

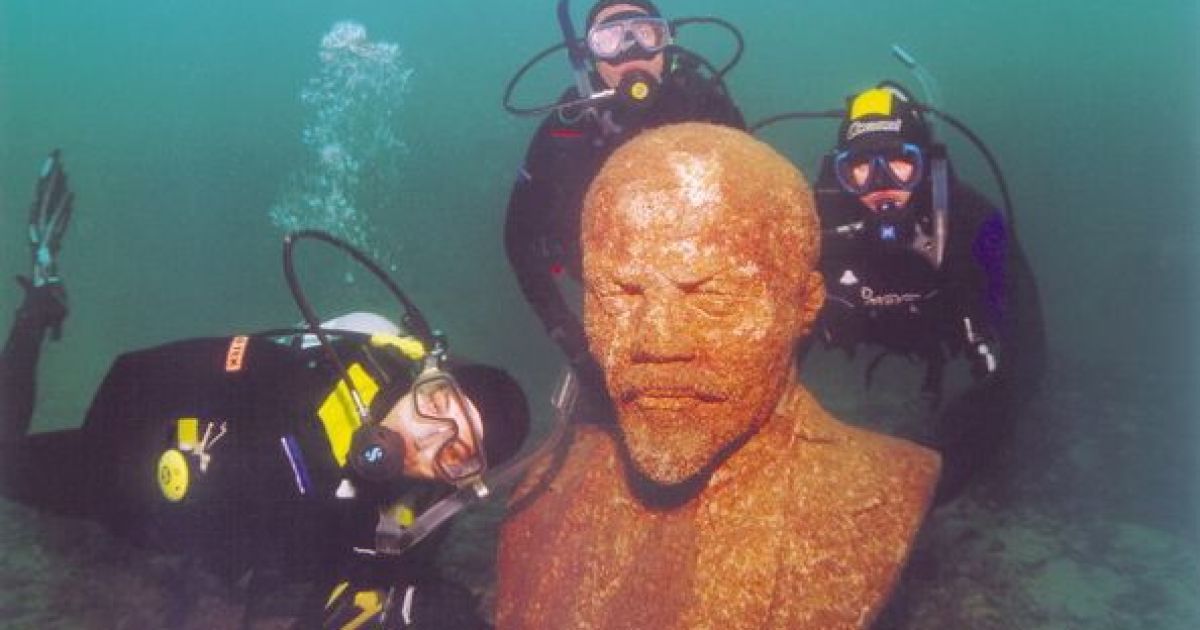

Lenin and Marx joined together like two corals, with a colony of Soviet fossils extending into the distance. Photo by Provincialynews.ru via maratakm.ru

The surrogate future

In the case of the post-Soviet subject, the aspiration to surmount the ego’s spatio-temporal limitations, to see the continuation of oneself and one’s desires in all contexts, has its own distinctive condition. The post-Soviet subject experiences a traumatic split with an the older Soviet symbolic universe; the ruination of a coherent historical narrative; the destruction of the familiar object world and its social context (from the practices of everyday life to industrial labour and now-destroyed factory buildings in which people clocked in and out every day); a discursive deficit associated with the insufficiency of the new languages required for depicting the new reality; the melancholic fixation upon the lost object of desire; the nostalgic attachment to what has gone that then engenders an excess of the past which the consciousness of society is unable to digest.2

This is the basic conceptual scheme on which a depiction of the post-Soviet era is built, especially the decade just before the ‘new stability’ of the Putin era. How the post-Soviet political elite use this affection for the past is a whole other conversation. Here, the question is how the post-Soviet subject feels in this apparently hopeless situation. I don’t think that it would be exaggerating to say that it feels just fine. The post-Soviet subjectremains trapped in a traumatic state of transition; it has comfortably settled into the spaces of an unfinished modernization, making it a bearable, habitable environment by turning the excess of the past — which is far too much to bear — into a surrogate future. By converting the discursive deficit into the basis of a new poetics, the post-Soviet subjectstakes to theircultural trauma like a fish to water.3

The traumatic symptoms bring a perverse satisfaction: nationalism and xenophobia compensate for the fall of the empire, and the unwillingness to remember one thing is balanced against the heightened feeling of commemoration for others and the nostalgic fixation on the past is recoded into a ‘project of modernization’4.

Melancholy becomes a mechanism of manipulation used by both the melancholic subject, who has learnt how to control its feelings of loss, and the political elites, who have learnt how to control the melancholic subject.

Hanging over all of this is the warm homely sphere of narcissistic infantilism. This facilitates the feeling that the ‘Other’ is, in fact, oneself, which turns the external into the internal and alters the boundaries between the ego and the outside world. The union of melancholy and infantile narcissism spawns a particularinterpretation of history and a particularform of historical representation. The loss of the former symbolic universe brings freedom from the ruling hierarchical system, from the old rules, norms, and sanctions. Infantile regression allows for the arrangement of a diverse combination of smashed fragments, symbols, and ideological forms from former eras without distinguishing the familiar from the alien and, in general, eliminating the verycategory of the Other beyond the limits of narcissistic fantasy.

If previously the image of a submerged Atlantis appeared as one of the important historical symbols of the ‘alternative’, generating a fantasy of a social order different from the existing one, then modern fantasies cannot come to terms with the unattainability of the lost object. This unattainability brings to mind the traumatic presence of the Other. If previously Atlantis had to disappear to be preserved forever, now its ruins have to be reproduced to allow the fantasy to meet up with its object. Now, however, the object is no longer the unattainable Other, but a projection coming from the narcissistic subject itself.

The new holism of history and nature. Photo via MirCrimea on Twitter

Under the sea

It is precisely this that has taken place on the western shores of the Crimea, not far from the rocky banks of the Cape of Tarkhankut. It was here that, in the year the Soviet Union collapsed, Vladimir Borumenskii, a retired colonel from Donetsk, installed a toppled Lenin monument from his home town. The Soviet Atlantis quickly sank to the sea floor.

The statues of these defeated gods had been littering the back yards of local history museums or quietly disintegrating on their now-profaned podiums. Borumenskii’s first attempt to save one of these former sacred objects did not meet with success. The following year, he discovered the Lenin statue lying destroyed and headless. Then he had an idea that laid the basis for a project that has lasted for more than twenty-five years: if there was no place on land for such deconsecrated objects, they would have to be hidden underwater. To save the statue of Lenin from the new barbarians, the retired colonel decided to install it on the sea floor. Borumenskii was an enthusiastic diver and this clearly influenced his decision. In an interview, the leader of the Tarkhankut divers discussed the date of the statue’s removal to its new watery site.

This was only the beginning. A whole underwater museum gradually began to take shape. The man-made ruins of Atlantis vanished from the surface of the earth and were carved into the landscape of the sea floor. Year after year, diving enthusiasts visiting the Tarkhankut diving centre brought discarded statues and busts of Soviet leaders and cultural figures. As a result, the underwater ‘Alley of Leaders’ grew to include sixty pieces. You can find Karl Marx, Klim Voroshilov, Joseph Stalin, Alexander Zinoviev, Felix Dzerzhinskii, Sergei Kirov, Nikolai Ostrovskii and Maxim Gorky among those buried at the bottom.5

What was rapidly deconsecrated as a result of perestroika was overturned by a second, local, reconsecration after the fall of communism. This placed the symbolic fragments of a shattered civilization in another order of access with another temporality and a different historical narrative. The sea floor around Tarkhankut is rich with the traces of former shipwrecks and fragments of ancient Greek amphorae, old coins, and other artefacts dating back epochs, each with a very different type of culture/nature relationship.

In the past, the submerged objects were products of grey socialist realist visual propaganda. They were, as such, an important part of the symbolic exchange that held Soviet society together. Nowadays, they are an unstructured mass of decaying, but accidentally surviving, objects, filling the stalls of flea markets. Memorial diving enthusiasts buy objects that are past their cultural sell-by date, saving them from the scrap heap in their own towns and cities. By submerging their salvaged goods, they subject them to an inescapable remythologization process.

The ‘museum frame’, the ability to add to the ‘collection’, and the process of viewing it, differ drastically from conventional ‘museification’, which endows subjects with the status of aesthetic objects or historical sources. When buried at the bottom of the sea, immortalized underwater, they get another status: they don’t appear as artistic productions, and even less as historical sources. Taken from the cycle of post-Soviet modernity, and the antiquities market, they become sacred once more. Concealed in the obscure sea depths, they are endowed with immobility, lavished with care and attention. Excluded from social and symbolic exchange, they stand still, their origins obscure to those looking on from outside. Forums and photo galleries displaying images and videos from Tarkhankut are full of comments like, ‘How beautiful! But how did they get there?’ or ‘Someone explain to me what on earth this is!’

Drowning in the social unconscious

In Soviet society, the sacred was, perhaps, found in ideology, including material objects of propaganda. Now, in a time with no ideological anchor, and with capital replacing ideology, maybe the memory of a bygone Soviet past fulfils the role of an unseen toehold. Having shed the initial sacred references to ideology, this memory cuts through the former era with symbolic fragments, which become subject to ‘surrogate sacralization’ onto which the post-Soviet subject can focus their unconscious projections and aspirations for self-identification.

The visitor’s descent is, then, nothing other than a dive into the depths of Soviet historical memory. A phantasmagoric combination of historical figures, heroic events, mundane items of daily life, and fragments of personal memories await the post-Soviet ‘diver’. This entire world – fragmented in the dive and at the bottom of the collective memory – is permeated with the infantile oceanic feeling. This is a world of tamed sanctity, and yet remains a stable fulcrum of post-Soviet society around which it continues to move. The dismantling of the Soviet symbolic system activates regeneration of its ruins in the melancholic and narcissistic unconscious of the post-Soviet subject. This system, destroyed onthe surface of the real social life, has now plunged into the social unconscious, dislodging the sediment left by the new order of things. Once the visual world has been reorganized like this, it becomes the material for the future construction of a collective memory, which is then ontologized. This makes it seem not only like this is the way social life is, but the only way it could ever be, which muddies the history of its formation over time, making it opaque even to itself.

Its creator sees the basic motif of the emergence of this underwater gallery as the conservation of monuments of the symbolic order of the Soviet past:

I never had any great love for the Bolsheviks, but when they began to melt it all down to scrap metal and sell it abroad, I began to understand that even the greyest examples of visual propaganda of the Soviet era would soon become rarities, even though they have no artistic value. So then I began to send sculptures to the bottom of the sea.

However, the very character of this conservation – its technological context and poetic semantic intonations, the way it turns an individual initiative into a huge amateur pursuit – allows one to speak of something bigger than the desire to maintain, popularize, and commercialize the remnants of Soviet culture. Even though it is difficult to imagine most museum curators finding the sea floor an auspicious place for artefact conservation, and although the need to dive twelve metres limits the number of visitors, the underwater museum has become one of the Crimean coast’s main tourist attractions.

The narcissistic post-Soviet subject meets with the soviet object of its loss. Photo by Melisenta from Photo.i.ua

Underwater melancholia

This underwater gallery of former leaders is the product of the collective desire of post-Soviet divers, coming from all corners of the former Soviet Union. These objects from the Soviet past, taken from everyday circulation, desacralized, but cared for from the desire to preserve them, should be looked at more as a collective symptom of post-Soviet historical consciousness than anything to with the official historical policy of post-Soviet states. This symptom can be found where melancholy and the infantile oceanic feeling meet. Melancholy deals with the lost reality through these objects, restoring an imaginary link to them in the fantasy space of the sea floor. The oceanic feeling lets people live the fantasy of the world’s lost unity, making ‘historical’ time fit their internal experiences. The former symbolic order then becomes the basis of a fairy tale about an underwater kingdom where Lenin and Stalin hang out amongst the seaweed, fish, and molluscs. The aetiology of this symptom is defined by how melancholic affect unfolds into infantile regression. This makes melancholy the ideal habitat for the post-Soviet subject.

In Mourning and Melancholia, Freud outlines the basic psychoanalytic dialectic of melancholic forgetting: having lost the attachment to the object of affection, the subject experiences it as a real loss of the object. In the face of such a loss, the libido, which was once invested in the lost object, turns on the subject, putting it into a state of self-abasement. The paradox is that this is the result of the subject’s narcissistic identification with the lost object to which it experiences ambivalent feelings of ‘love-hate’. Punishing itself, the melancholic subject punishes the Other, the loss of attachment to which it experiences as a real loss. Therefore, melancholic suffering is difficult to distinguish from pleasure.6

This mechanism of melancholy can be applied to the subject’s experiences of both perestroika and the post-perestroika era.7 Lamentations about peoples’ collective fate, personal lives, and the dark pessimism that is the leading genre in representations of everyday life under perestroika have all acted as an actively corrosive element that played its role in the destruction of the Soviet order. The loss was played out until it actually happened: the extreme (painful-ecstatic) experience of separation from the communist regime anticipated its fall and, in many ways, predetermined it (consistently reproducing the Freudian logic, according to which melancholy induces the loss of attachment as the loss of its object). However, the past twenty years history of post-Soviet melancholy has endured more than just one stage.8

Melancholy, having expanded as a reaction to and intensification of the political, economic, and socio-cultural crisis, has become not only a habitual means of adaptation, but a conduit for a peculiar emancipation from that order, whose loss it has dramatized. The loss of attachment, melancholy, the object’s real disappearance (which doubles the melancholic affect), and the narcissistic identification with lost object, led initially to the subject falling into a stupor, repeatedly going over its negative experience of loss. This characterizes the 1990s. But then, the ever-repeating movement of this libidinal ballet became so habitual that it allowed the post-Soviet subject to assert itself in the wide-open space of loss, having internalized the formerly external Soviet order. This characterizes the 2000s. Having ultimately arisen thanks to the sense of melancholy, the narcissistic identification with the loss allowed the post-Soviet subject to introject the former regime, taking it into itself, although not in the form of a prescribed normative system but in the form of its deconstructed and abandoned fragments.9

In some ways, the subject only became truly Soviet when it could make the ‘Soviet’ part of its infantile narcissistic fantasy. If its ‘Sovietness’ was once the result of an interpellation by an external ideological force, now it has become an effect of its own narcissistic identification, brought about by ‘democracy’ and ‘market choice’, when the object of such an identification is selected by the subject’s own desires. Although the ‘authentic witness’ of the past, which became a part of the post-Soviet subjecttrying to build a new identity, turned out to be the product of its own narcissistic fixation on a lost tradition whose symbolic thesaurus has been fragmented and decategorized. So now the narcissistic-melancholic libido swims freely in the flowing space of tradition, now divested of its once rigid structure. The details of the destroyed symbolic carcass of the USSR have now gain a second life, settling on the bottom of the collective memory and building individualized and fluid images of a Soviet Atlantis.

This is how the underwater museum tells its story or, in the words of its founder, its ‘philosophy’. The monuments are not just submerged, they actively create clearly-defined scenes on the sea floor, reflecting the ideas of the gallery’s creators. We are faced not only with works about what has been lost, but also about loss management and the reconstruction of a lost object in new forms to fulfil the desire of the melancholic subject. So, for example, the busts of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Yesenin, Shukshin and Vysotsky, laid out on an alley higher than that of the leaders, ‘neutralise the Bolsheviks’.

The underwater world, just like the unconscious, lives according to its own laws and writes its own history. It is exactly here, in the ‘sea floor unconscious’, that the post-Soviet subject gets the chance to build its own private Soviet Atlantis, whose ruins remind it of the loss of something that it never owned. Melancholy and narcissism allow this subject to internalize something that was once external and that never belonged to it. In our case, we see how this substantialization of the ‘Soviet’ takes place: the ruins of the social order are presented as part of the natural order. The unreality of the sunken landscape, where statues of Beethoven and Blok stand side by side with busts of Lenin and Dzerzhinsky as creatures of the deep swim by. This directly references the landscape of the post-Soviet unconscious, which assimilates something once external to the former Soviet subject when it has made its own fantasy reality. Of this appropriation, Giorgio Agamben writes that

it is possible to say that the melancholic libido’s turning to itself has as its aim the appropriation of something that, in principle, it is impossible to assimilate. The libido behaves exactly as if the loss has taken place though, in reality, nothing has been lost. In such a way it plays out the loss, simulating the scene in which something that could not be lost (as it never belonged to us) is presented as lost while the thing that never belonged to us is appropriated in the form of a lost object.10

What Agamben does not write, however, is that this appropriation requires a regression to a state of infantile narcissism. This provides an opportunity to identify the continuation of oneself in the environment and to meet with the fantasmic object that is a projection of the subject’s own desire. The euphoric glee this meeting produces takes place in the depths of the sea off the Crimean coast, where objects that once belonged to the normative sphere of the Soviet subject’s super egonow placed in the subaquatic post-Soviet id. This displacement stages the appropriation of something lost that was never fully owned, making it part of the internal world of the new subject of the post-Soviet epoch.

Photo by planetakrim.com via tsn.ua

Postscript

Alexander Solzhenitsyn opens his tale ‘The People of the Convicts’, with the following scene:

In 1949 myself and some friends fell upon a note in the journal Nature of the Academy of Sciences. There it was written, in small print, that an ice lens was somehow discovered during an excavation by the Kolyma River – an ancient frozen flow which held frozen fauna that have been fossilised some tens of thousands of years ago. Whether it was fish or newts that had been kept so comparatively fresh, the writer witnessed how those present, having cracked the ice, WILLINGLY ate them.11

For Solzhenitsyn, this treatment of the prehistoric remains was necessary not only to emphasize the monstrous conditions of life in Stalinist camps, which forced the inmates to ‘willingly’ eat the fossilized remain of ancient fauna:

‘We saw the whole scene down to its finest details: how those present broke the ice with an indecent haste; how trampling the higher interests of ichthyology they elbowed each other out of the way and gnawed off the pieces of prehistoric meat down to the bone, then relaxed fully satiated’.12

In addition to the extremes of camp life, this extract widens the historical horizon of events. The (in)human history of the twentieth century falls into the geological epoch of the ancient inhabitants of earth, becoming a subject of ichthyology or paleontology. Eating the prehistoric meat of a fossilized newt, the person performs a reverse evolutionary movement: his phylogenesis is reversed in the direction of his primordial ancestors. In addition to this, the newt was one of the gods of ancient mythology, the messenger of the sea depths, the son of Poseidon. As a consequence, this regression has not only a biological but a cultural-historical significance. In Solzhenitsyn’s description, Soviet history is presented as an ‘archaization’ of the social relations of the present, a jump backwards to humanity’s earliest existence.

Referring to this episode, Alexander Etkind and Mark Lipovetsky see in it the first evidence of the collective trauma that Soviet history inflicted upon a society. In their view, its constant revisiting is a fundamental symptom present in post-Soviet literature.13

My personal view is that the history with the underwater museum of Soviet leaders is a variation of this revisiting of the ‘Soviet newt’. Although, in this case, we are dealing not only with the painful repetition of a traumatic event, calling for a reactive ‘working-through’ of the problem and Freudian ritualized mourning, but also with the melancholic joy that is transferred onto the post-Soviet subject as it meets the object of its narcissistic desire.

Not requiring any relation to the past, and not allowing the past to complete itself, melancholy not only gradually destroys its subject from within, but also ensures that history returns to its traumatic origin. So, in 1991, going underwater on the Crimean coast, the Soviet Atlantis once again surfaced twenty-three years after its submersion in the depths of the sea. Thus, the Soviet empire, having collapsed as an historical and geopolitical reality, was reborn in the spring of 2014 (in a different symbolic form) when Crimea was annexed and united with Russia. Now the past, which had been lurking at the bottom of the sea and repressed in the unconscious of the post-Soviet subject, once again became the present.

Sigmund Freud, ‘Civilization and its Discontents’, trans. by Joan Riviere, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol.21, ed. James Strachey, Vintage Press, 2001, p.35

See for example Maya Nadrani and Olga Shevchenko, 'The Politics of Nostalgia: A Case of Comparative Analysis of Post-Socialist Practices', Ab Imperio: Theory and History of Nationalities and Nationalism in the Post-Soviet Realm, 2/2004, 487-519; Shevchenko, Olga, Crisis and the Everyday in Post-Socialist Moscow, Indiana University Press, 2009

For more on the discursive specifics of the language of self-description characteristic of the post-Soviet subject see Oushakine, Sergej, 'New Lives of Old Forms: On Returns and Repetitions in Russia', Genre XVIII, Fall-Winter 2010, 409-457.

For a discussion of both the modern Russian modernization project, announced in the second half of the 2000s during the presidency of Dmitrii Medvedev, and of modernization based on the management of the nostalgic effect see Ilja Kalinin, 'Nostalgic Modernization: the Soviet Past as a “Historical Horizon”', Slavonica 17/2, 2011, Special Issue: Between History and Past: Soviet Legacy as the Traumatic Object of Contemporary Russian Culture, 156-167

For a short history of the creation of the museum and a description of the collection see: www.evpatori.ru/podvodnyj-muzej-tarxankuta.html.

Sigmund Freud, 'Mourning and Melancholia', trans. Joan Riviere, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol.14, ed. James Strachey, Vintage, 2001

See Jonathan Flatley, 'Moscow and Melancholia', Social Text 19/66/2001, 75-102; Nancy Ries, Russian Talk: Culture and Conversation During Perestroika, Cornell University Press, 1997.

See Kevin Platt, 'The Post-Soviet is Over: On Reading the Ruins', Republics of Letters: A Journal for the Study of Knowledge, Politics, and the Arts 1/1/2009, 1-26.

On general psychoanalytical approach to melancholy and object relations theory see Melanie Klein, The Collected Writings. Vol. 1. Love, Guilt and Reparation: And Other Works 1921–1945, Hogarth Press, 1975; Donald Winnicott, Playing and Reality, Tavistock Press, 1971

Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, Minneapolis University Press, 1993, 20-21.

Alexander Solzhenitisyn, The Gulag Archipelago, Vintage, 2018, 5 (emphasis author’s)

Ibid.

Mark Lipovetsky and Alexander Etkind, 'The Salamander's Return: The Soviet Catastrophe and the Post-Soviet Novel', Russian Studies in Literature, 46/4/2010, 6-48

Published 22 November 2019

Original in Russian

Translated by

Gayle Lonergan

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Ilya Kalinin / Eurozine © Ilya Kalinin / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Russian art museums and galleries, navigating Putin’s censorship, either conform or risk closure. Dissenting cultural workers are sacked, artists arrested. Pro-war propaganda is both sardonically replacing exhibitions once celebrating Soviet Ukraine in Russia and eradicating Ukrainian culture in the occupied territories.

Intellectual violence

The militarization of education in Russia

Education has become another battleground in the Kremlin’s campaign to militarize the Russian public consciousness. Youth organizations, book bans, changes to school curricula – all amount to a ‘special anthropological operation’.