How do I write above the clouds my kin’s will? And my kin / leave time behind …, and my kin / whenever they build a fortress they raze it to erect above it / a tent of longing

‘How do I write above the clouds?’, asked Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian poet. How do I write above the clouds my kin’s will? Strangers pass by carrying seven hundred years of horses on an Earth that was not his; only the keys to the sky were. Darwish, who so poignantly wrote about the anguish of dispossession and exile, exited the wrinkles of his time following his own will: to be expelled slowly, to be killed quickly, beneath his olive tree, with Lorca.

For the past few months, Yasmin Huleileh, Ahmad Alaqra, Andrés Burbano and I have been organizing I Will Write Our Will Above the Clouds, a series of events aimed at raising funds for Gaza. It all began with Darwish, whose cries we still hear, perhaps even louder today, even after his passing. Each morning, I wake up to the news and think of my friends in Gaza: ‘Are they alright?’

There is barely any electricity there, and connection to the Internet is scarce. Amer Nasser photographs are a means of survival. He climbs mountains of rubble, hoping to find connection, to send a signal. ‘This is how we survive,’ he says, ‘with the word “barely” written everywhere: this is barely a house, this is barely a cup of tea, this is barely living’. Like NASA spacecraft Voyager 1 in 1977, traversing the vastness of space, he tries to send his signals into the void, hoping someone, somewhere, will receive them – and remember.

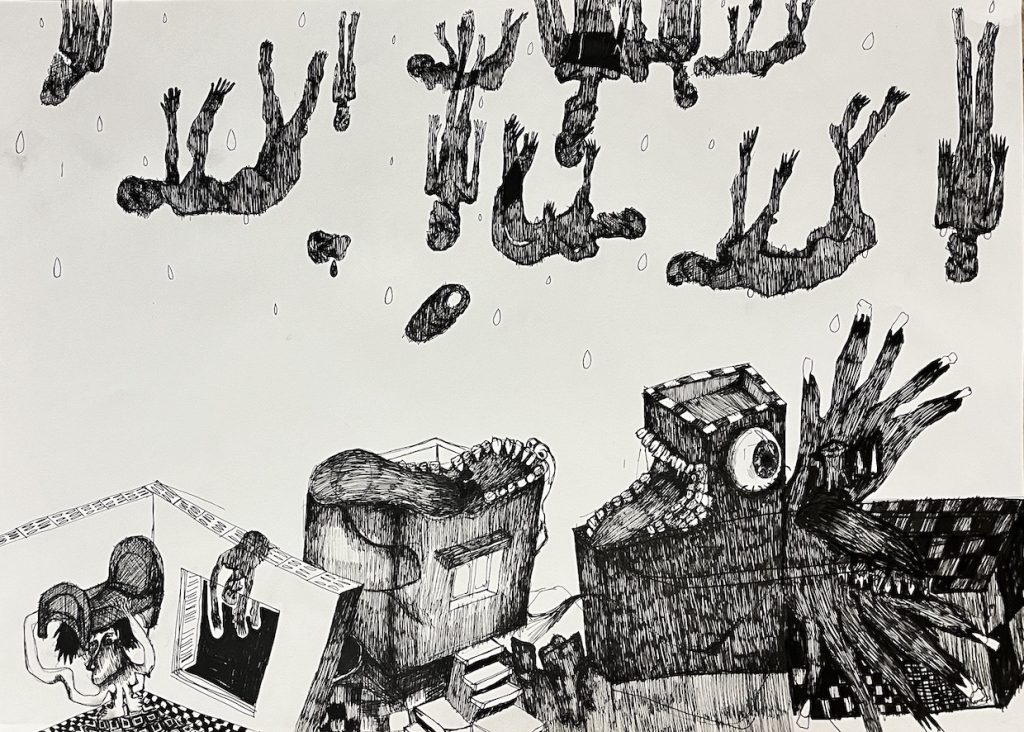

If they leave, they leave a land to be taken; but if they stay? Artist Amal Al Nakhala imagines the day when corpses will start falling from the skies:

I’ve been all in ‘sway’, watching or rather reliving each massacre … and now it’s simply become normal routine you see daily, passing by it as if you are passing by trash or something. … It’s become so normal for my people to decompose, be burned, amputated, for their flesh to fall, disintegrating from the bones, for their corpses to be eaten by dogs, for babies to be killed in their mothers’ wombs. I wouldn’t even be shocked if once the sky would simply rain people from all of these endless bombs.

Is this how one writes their will above the clouds?

Artist Bayan Abu Nahla regrets evacuating Gaza. She managed to leave through a health transfer to Egypt, only to find there were no doctors nor hospitals, only a detention centre and months of utter isolation: ‘take me back to Gaza, where at least hugs are like nowhere else.’

Artist Shereen Abdelkareem, on the other hand, dreamed of taking Gaza with her. She wanted to carry her home, her grandfather’s house, the mosque that her grandfather loves, her university, her workplace, the café where she met her friends, her neighbourhood bakery, her neighbours’ homes, the hospital where she was born. She wanted to take her dreams with her, her memories, her childhood, her prayers, her days, her present, her past, her future. But her ‘bag wasn’t big enough’.

Over time, Abdelkareem’s resolve shifted; she doesn’t want to take Gaza with her anymore: ‘As for me, leave me here’ … ‘We will never forget, even if we lose our memories’. And so begins the tenth exodus towards death.

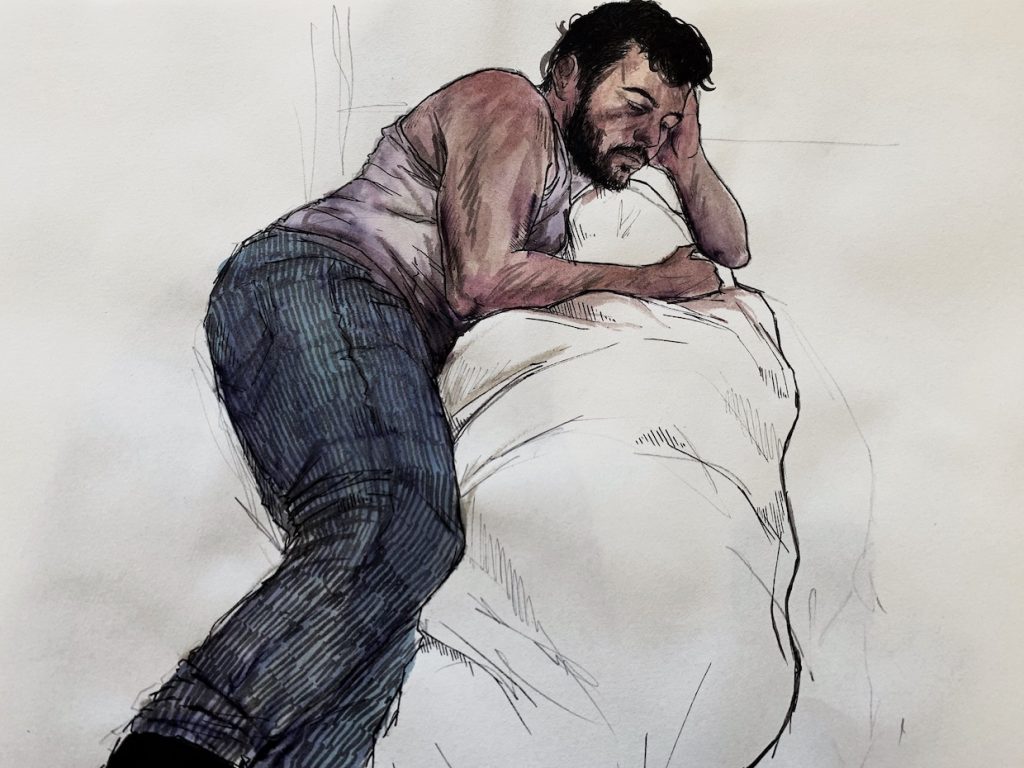

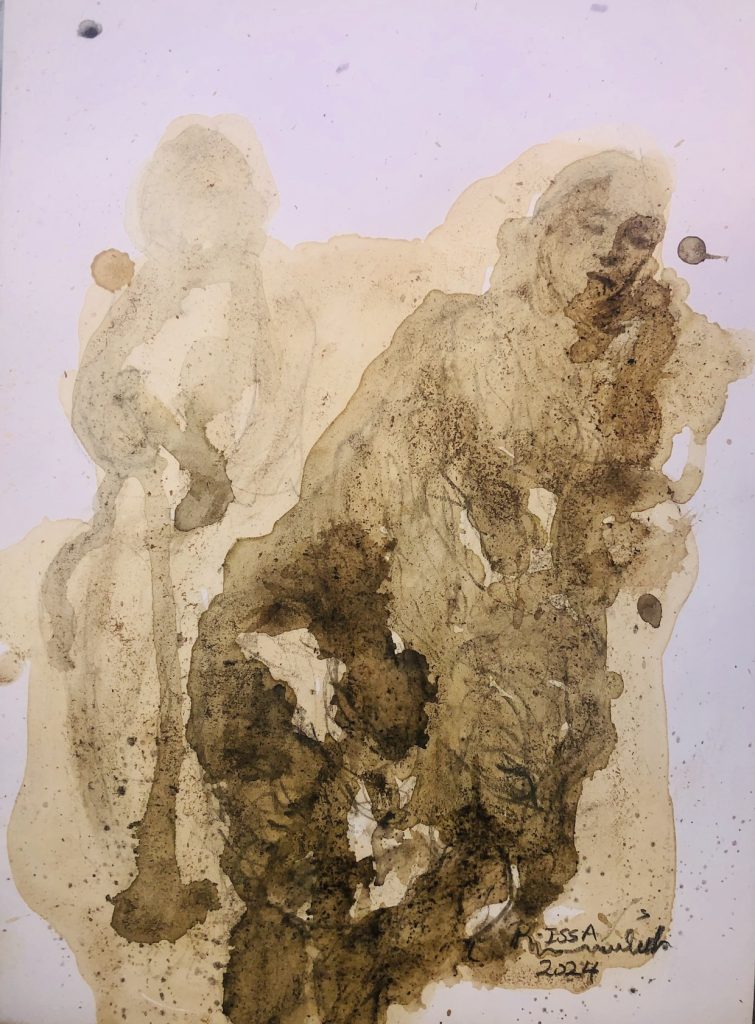

Artist Sohail Salem’s serene and peaceful oils on canvas are now erratic strokes, scribbles of anguish etched onto notebooks. Artist Raed Issa, who longs for a simple cup of coffee, uses dregs instead for his art – now his only available drawing medium. Since 7 October artist Maisara Baroud has made sure to stay in touch with his friends as much as possible, reassuring them daily through a new sketch via another post on Instagram. These drawings are his way of saying ‘I am still alive’.

Baroud strives to document the war, capturing the details of every account – the destruction, patience, hunger, weakness, displacement, pain, brokenness, death and resilience, thus transposing stories of a war that unleashes incommensurable harm. Planes and missiles have destroyed all his dreams and possessions, but they couldn’t take away his passion and love for drawing.

Our series, I Will Write Our Will Above the Clouds, began as an effort to showcase past works that had been destroyed – bombed, buried under rubble. Now, it includes works being created in the present: in tents, in pain. Each time one of the artists doesn’t reply for more than three days, we live in anguish. Then, their response arrives, and we carry on.

The pieces we showcase are digital copies – another meaning of ‘the clouds’. Nothing can enter or leave Gaza. Thousands of aid trucks wait at the border, barred from crossing while Gazans starve. We will write our will above the clouds, for the digital cloud is our only communication lifeline. Our only way to receive, as Nasser says, ‘signals of life’.

How would Darwish’s poetry convey all of this if written today? Will we write our will above the clouds? Inside a tent? Beneath the moon? Under the shade of an olive tree? Will we write our will with something other than blood? ‘The olive grove was always green; / It was, my beloved. / But tonight / The blood of fifty victims / Has turned it into a red pool. / Please don’t blame me / If I can’t come; / They’ve murdered me too’.

The names in the text are the real names of Gazan artists whose work we exhibit, except for Mahmoud Darwish, who is no longer with us. The names in the text are the real names of our friends. And all of this is for them.