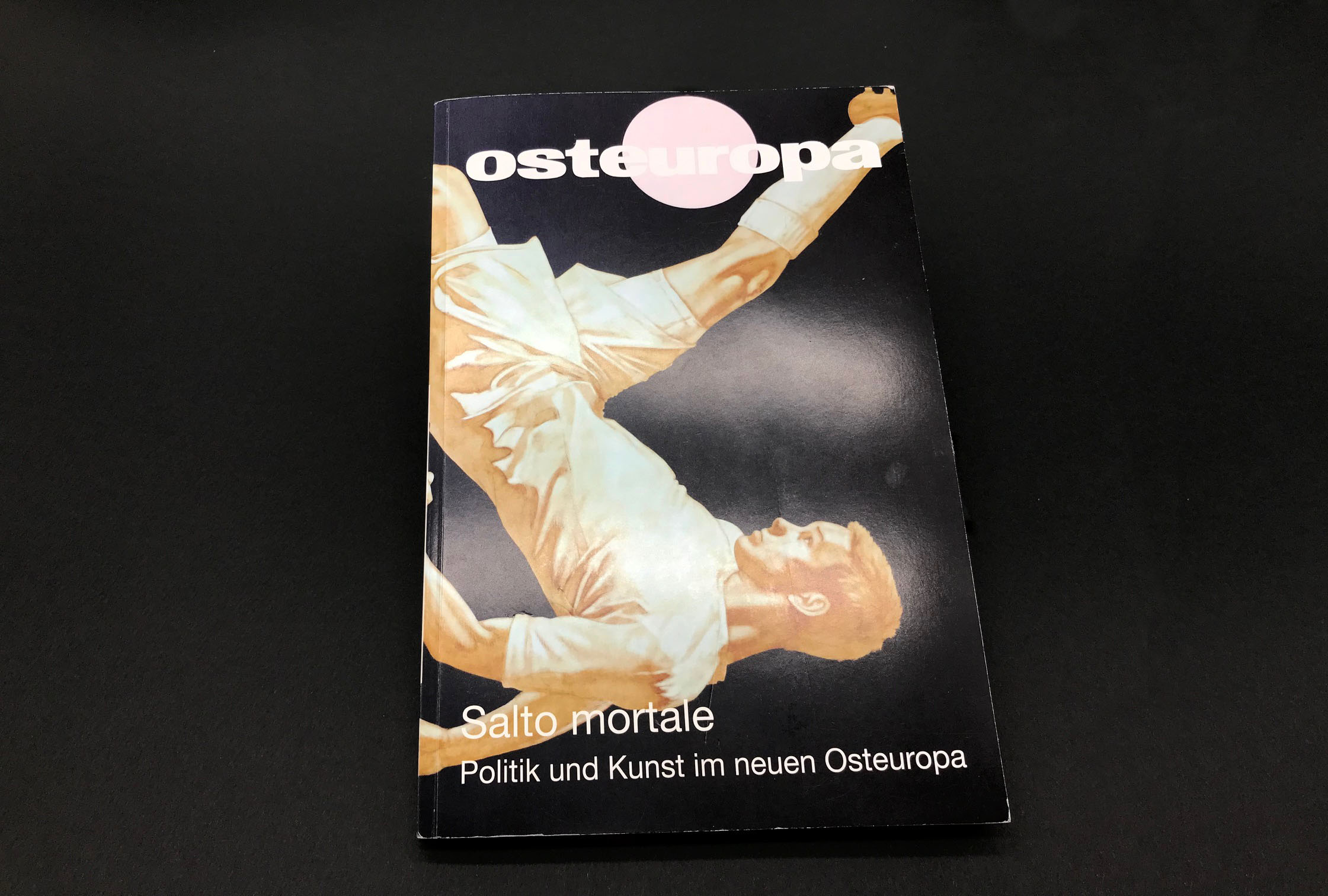

‘Artists and writers are the seismographs of society’, write the editors of Osteuropa in their introduction to an issue on politics and art in the new eastern Europe. ‘Earlier than others, they indicate the waves that precede political upheavals. In many countries in eastern Europe, this early warning system has shown up growing social tensions. Art and literature have politicized visibly.’ Contributions focus strongly on Russia as the origin of distinctly contemporary intersection of countercultural aesthetics and conservative ideology.

‘Artists and writers are the seismographs of society’, write the editors of Osteuropa in their introduction to an issue on politics and art in the new eastern Europe. ‘Earlier than others, they indicate the waves that precede political upheavals. In many countries in eastern Europe, this early warning system has shown up growing social tensions. Art and literature have politicized visibly.’ Contributions focus strongly on Russia as the origin of distinctly contemporary intersection of countercultural aesthetics and conservative ideology.

Avant-gardes

Lena Jonson warns against conflating artistic transgression with an emancipatory ethos. Rather, as she shows in her genealogy of aesthetic subcultures in Russia since the 1990s, it is all about context: the Moscow activism of the early 1990s was, despite or because of its anarchy, largely in tune with the liberal mood of the period. In contrast, the ‘neo-academicism’ that emerged in parallel positioned itself against what it saw as the chaos of Perestroika. Ironizing and homoeroticizing the aesthetics of Soviet high realism, neo-academicism was a cult among the youth of St Petersburg. Later in the decade, it drifted towards the ultra-conservativism of Alexander Dugin and Eduard Limonov, to the distaste of the liberal intelligentsia.

With the rise of ‘constructivist etatistauthoritarian conservatism’ (Jonson), the tables began to turn. Actionism became overtly political and paved the way for the middle-class protests of 2012. Simultaneously, an anti-liberal and Kremlin-loyal school of neo-realism emerged in connection with the hyper-nationalist turn in cultural policy, whose exponents were the heirs to the neo-academicians of the previous decade. ‘A conservative former counterculture in art had by the middle of the first decade of the 2010s become part of a conservative mainstream’, writes Jonson. Liberal art, on the other hand, ‘became marginalized, primarily on the state-financed art scene but to a large extent also on the private art scene’.

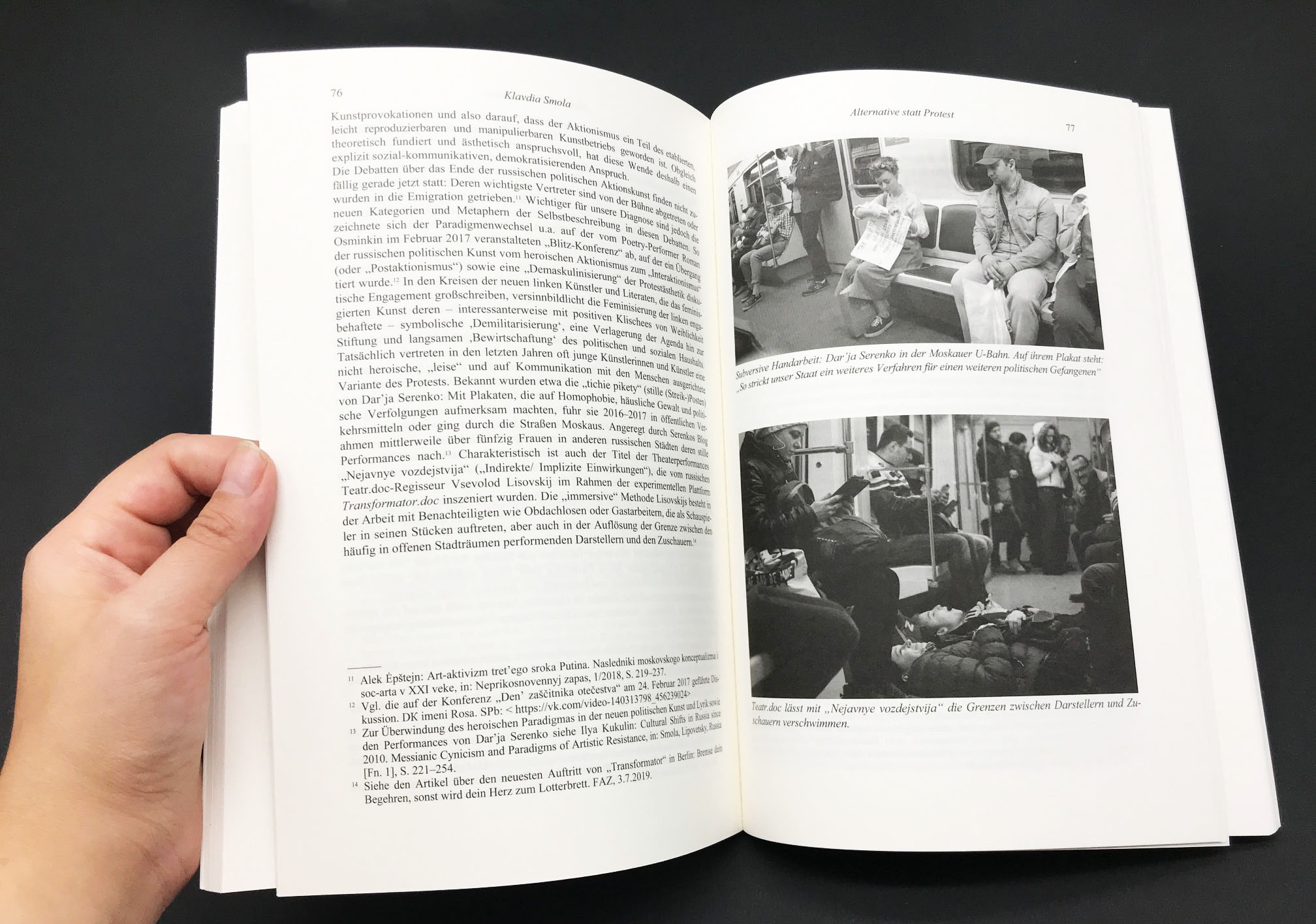

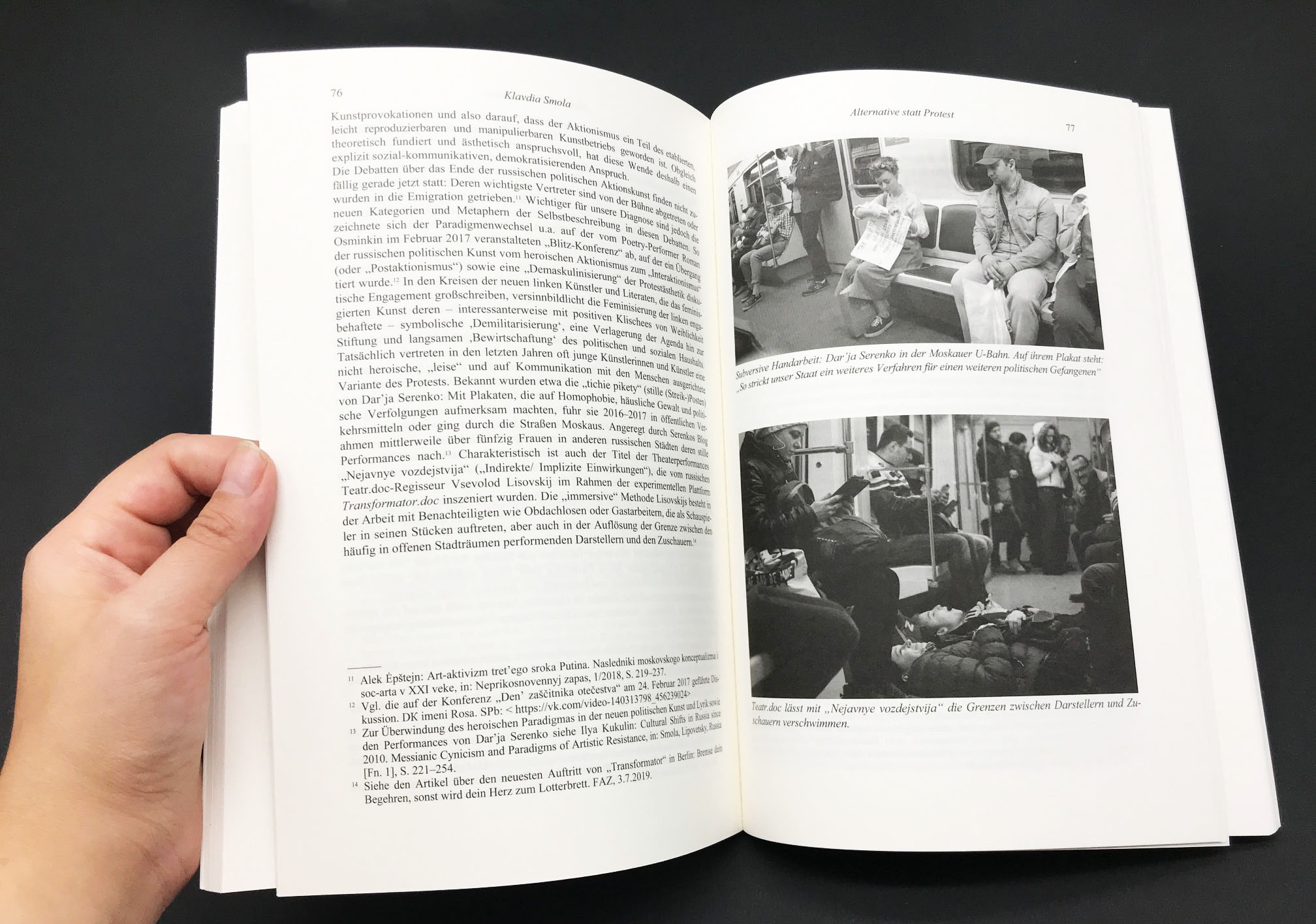

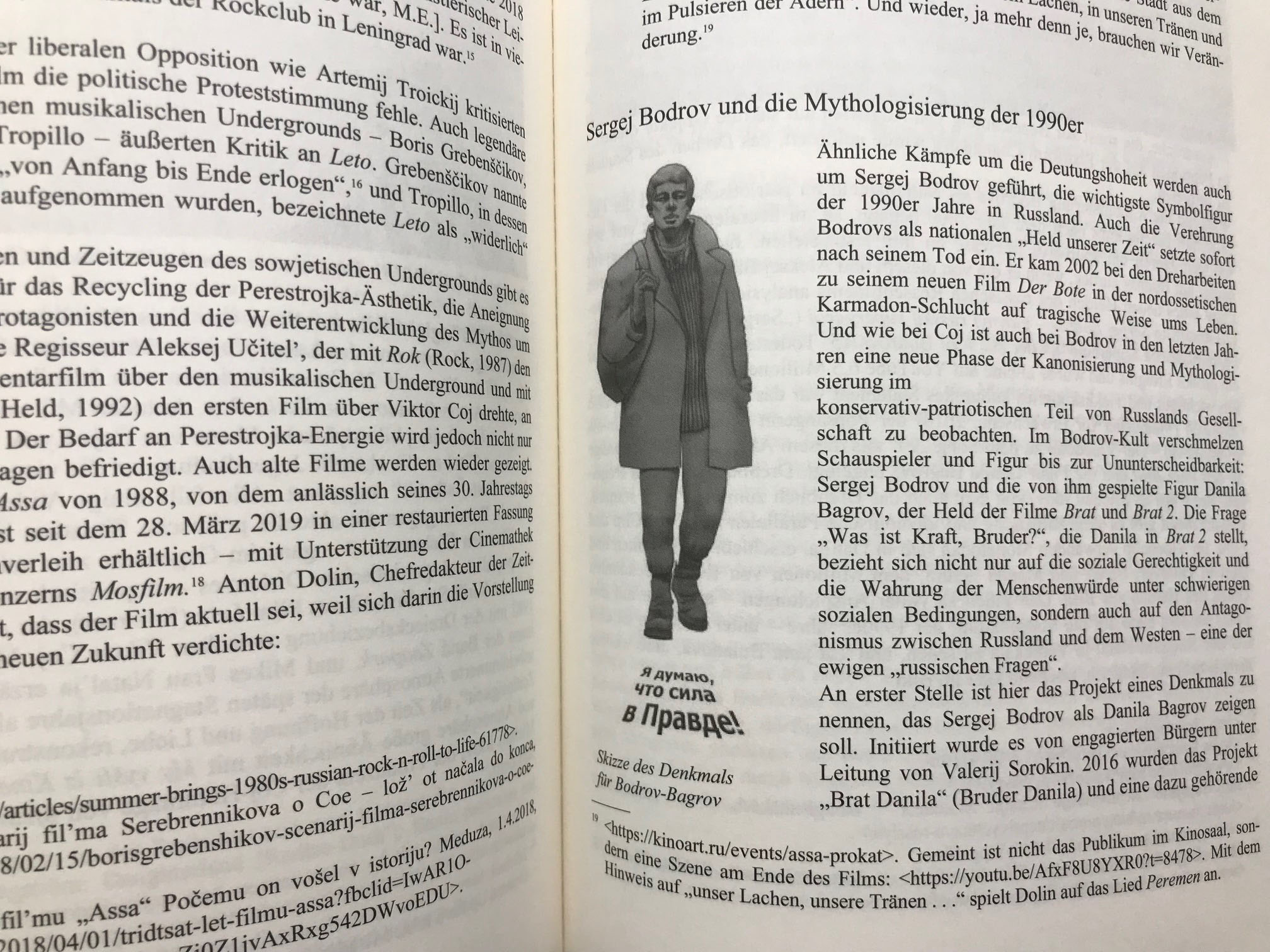

Also: Mark Lipovetsky criticizes the labelling of the politics of the Kremlin as ‘postmodern’ and shows how the current regime hollows out the critical thrust of postmodernism proper. Marija Engström shows how the legacy of the late-Soviet underground has undergone ideological and stylistic recycling, as contemporary Russian art becomes the commercially attractive imitation of revolution. Klavdia Smolar argues that oppositional art has responded to the failure of the protests of 2012 by avoiding direct confrontation in favour of a participatory and socially transformative concept of art. And Maciej Urbanowski looks at the genesis of right-wing literature in post-communist Poland, pointing out correlations between key events in the conservative imagination and central ideological motifs.

This article is part of the 15/2019 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about latest publications and news on partner journals.

More articles from Osteuropa in Eurozine; Osteuropa’s website

‘Artists and writers are the seismographs of society’, write the editors of Osteuropa in their introduction to an issue on politics and art in the new eastern Europe. ‘Earlier than others, they indicate the waves that precede political upheavals. In many countries in eastern Europe, this early warning system has shown up growing social tensions. Art and literature have politicized visibly.’ Contributions focus strongly on Russia as the origin of distinctly contemporary intersection of countercultural aesthetics and conservative ideology.

‘Artists and writers are the seismographs of society’, write the editors of Osteuropa in their introduction to an issue on politics and art in the new eastern Europe. ‘Earlier than others, they indicate the waves that precede political upheavals. In many countries in eastern Europe, this early warning system has shown up growing social tensions. Art and literature have politicized visibly.’ Contributions focus strongly on Russia as the origin of distinctly contemporary intersection of countercultural aesthetics and conservative ideology.