Ten days before the opening of my degree show, I received a message. You were dead. After seventy-two hours, they had finally pressed the stop button. You had been braindead already when you arrived at the hospital in the ambulance. That’s what they had said. Medically, there were never any doubts, but they had their routines to follow in this kind of case.

I was informed of the circumstances that had preceded your death via SMS. The number was not in my contacts and the message had no sender. One could tell it was written by a person in a great deal of shock. It was a Sunday afternoon, the last week in September and the winds were still mild. I had decided to take a day off to gather myself before the final edit of my video work, and then the installation and everything.

Now all I saw was that image: you in a hospital bed with a lot of tubes. I tried to push it away until later but didn’t succeed. I was with my dad’s ex-wife – we had been at the cemetery, looking at the tombstone that had finally been placed on his grave – when I received the message about your death. I didn’t say anything to her. It didn’t feel appropriate and I couldn’t even speak. The air was thick and it hurt to swallow. Without words and with a weird expression on my face, I hugged her goodbye and hurried away.

The image of you in a hospital bed was very clear to me. It had been close on one previous occasion. We hadn’t known each other for very long at that point. I’m pretty sure it was right after that first summer, because I still had my apartment. That time, you made it due to pure luck, with just a few minutes’ margin they said – if even that. But it had been several days and long nights, when you were hovering between life and death, and no one knew.

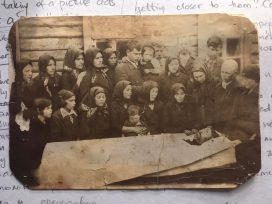

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’.

The only consequence then was an indefinite degree of long and short-term memory loss, which was of course not ‘only’, but, in that situation, considering everything that could have happened, it seemed rather minor. I even think you drove the car from the hospital. We were both surprised. But I might remember wrongly or be mixing it up with another time. Within a few days, we were back to normal. Which wasn’t quite normal.

The fact that you were dead now didn’t change anything. I mean, you wouldn’t have come to my exhibition anyway, that’s for sure. I wouldn’t miss you there, because you wouldn’t be there. Not that you would decline – you wouldn’t know. And not that I would ignore you, not at all. I wouldn’t even think about it. You didn’t belong in my new life. And I no longer existed in yours. It had to be that way.

So nothing had really changed. Yet, something was different, in an unspeakable, invisible way. It appeared as a dull ache throughout my body, which I first recognized as the beginning of influenza, and, later at night, those strange nightmares that only come with high fever. But there was no fever. It was a condition very unsettled, unspecified, I guess you could say, in the absence of the right words.

I carried on with the exhibition according to plan – in some kind of robotic manner, yet done well – without telling anyone at uni what had happened. It would have been too much to explain and there just wasn’t enough energy – or trust, for that matter. I couldn’t risk any comments about you (or us), which could have been interpreted as degrading or questioning, or with the slightest tone of aversion – even if it was only in my head.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

On a clear October day, the week after, I stood in the florist shop by the metro station close to uni and tried to remember your favourite colours. The fear of meeting those I had avoided in recent years made me not go to your funeral. I couldn’t trust myself in that situation. I decided to send flowers to the chapel and have my own ceremony on the day. The woman at the desk asked which farewell greeting I wanted. I chose to sign with my full name, to give your son the possibility of contacting me in future. The bouquet would be of blue and purple flowers, tied with many green leaves. I’m sure it was beautiful.

That autumn was longer than usual, outstretched in the way only time itself can operate. I stayed for a while in my friend’s apartment, while she was away. The long walks I usually took to process things were now in new areas. I spent a lot of time by myself – this wasn’t anything I could share anyway. Also, spending time with myself, in this case, meant spending time with you. And I needed that. I had missed you for so long.

There was also something shameful about losing someone who was already long lost. Like it wasn’t for real – above the shame that was already inevitable in deaths of this kind. I found no way to mute the thoughts in my head, the commuting between it could have been me and it should have been me, looping, until the dizziness forced me to lay down, or eat something – something warm or sweet. And then walking, aimlessly, for yet another hour.

Autumn finally gave way to winter. The more I tried not to think of you (or us), the clearer the pictures were once they appeared. Seemingly out of nowhere, one of them kept coming back. It could be anytime of the day but always when I was awake – awake in the sense of not sleeping, yet dreaming. I couldn’t help smiling, the kind of smile you cannot control by will. And you often smiled in the picture as well – looking calm, warm. Though the picture was very clear, it was somehow softened, like an old photograph. I wanted it that way.

Could it have been the first time you were at my place? I think so. We had only known each other for a couple of weeks if that. But we had been hanging out very intensely, so it felt longer than it was. You asked if you could rest awhile in my loft bed – climbed up and fell asleep, in the middle of a sentence. Later, I left a note on your shoes by the ladder. I didn’t want to wake you up. I went out and came back. Out again, and back again. Still sleeping. Like a child, or a person severely ill.

I never forget that moment, when it suddenly hit me: you actually lived in your car. How could I not have realized? You had probably not slept in a bed for a long time. Or even been safe, behind a door. I wondered how it was to go to sleep in a car. Or if you avoided it until it was no longer possible, and you just crashed without a thought. And the winters then? In Sweden. I felt so sorry for you. Six months later, I lived together with you. In that car.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

During the winter, which lasted until April that year, I continued working on my graduation project, a film about being locked in. For a long time, it was just folders with different script versions and a large amount of unsorted film material. I started to doubt the whole thing. Asking myself whether this was the right time or the right place to do this. If there ever would be such a time or such a place. I was looking for an excuse – a rather poor last attempt to escape the process that had started. Because, somehow, I knew. I had no choice. It was also too late to do something else.

I sat in the rental car with cheese sandwiches and lukewarm coffee, waiting for the rain I had decided to have in the film, when all the memories came to me. I had read an article about that psychological phenomenon, that you can recover forgotten memories by physically going back to a certain geographical place – memories not only connected to but also dependent on that specific location. So I knew it existed, but this was for real.

I can only remember one time, when we mentioned the future. That was in the mail correspondence we had, when we didn’t have our freedom. Geographically, we were very close, no more than a large field separated the blocks where we were kept. Yet, it usually took three to five days for a letter to reach the other. I think you mentioned it first. You wrote that we could go fishing. In the future. We could go fishing in different places!

In the library, just by coincidence, I got hold of a book which seemed too new to be in the system. I figured it must belong to the librarian herself since it had no barcode on the back. My too big sweater made it easy to hide. A sudden sense of satisfaction roused in me, though I hardly knew what it was about, more than that it was something to do with psychology. Months later, when I had lost count of both time passed and time left, I found the book again under my mattress. I started to read and couldn’t stop. It dealt with attachment theory and I couldn’t help wondering whether that knowledge would be good, or not.

The summer we were released (I, one month before you, as I had been caught one month before), your mum was severely ill. Because we had just come out, we looked very healthy and, with new clothes on, we seemed like a most decent young couple. Our appearance at the hospital made your mum cry. I could see in your eyes and on your posture, how proud you were to give her that picture. Carefully, we took her out in the wheelchair so we could sit down together and have a smoke in the blossoming backyard, in the sun. It was the last time we saw her.

When my mum got ill, a few years ago, I wanted to call you and was very close to it several times. My mum never had the social skills to pretend, so when she liked someone, it was for real. And once she had formed her opinion about someone or something, it was fixed like a mountain. I don’t know why, but she always liked you. When she died in my arms and the world as I knew it fell apart, I wanted to google your address and go there straight away. My memory is blurred, but I think I was stopped by my friend, who had come to the hospital to take me home.

Sometimes we had movie nights in the car. We’d parked in some deserted area on the outskirts of the city, where chances were good not to be disturbed. Usually we sold the portable DVD-players immediately to get what we needed, but sometimes we kept one for ourselves. We piled up loads of sweets, more than we could possibly eat, and put on different movies to see which one we should choose. You said that after fifteen minutes, if not before, you could tell if the film was worth watching or not. I had no reason to question you. The movie nights weren’t so much about the movies anyway.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

Gisela was a German shepherd we took care of for quite a while. Can’t remember the reason or who her owner was. It was probably the case of a sudden disappearance of some kind and we just happened to be at the same place as the dog at the time. She was almost deaf, which could cause trouble as we had to shout very loud for her to hear us, or wave our arms lively about – things you want to avoid when hiding and trying to be discreet. What happened to her when they finally took us off the streets, we never found out. I guess she just went on to somebody else, in the same way she had come to us. Gisela had developed typical co-dependent behaviour – it’s not uncommon for animals living in such conditions.

Many times we were entirely broke or even in debt, and our bodies were already in transformation – becoming weaker and weaker every minute – when we realized that it was too late to fix in time. Days of physical suffering were waiting for sure. Actually, the knowledge of that was worse than the pain itself. The pain, once it came, almost felt like a release. It was restricted to the body and clearly marked an end of some kind. It also made us feel alive and could have the effect that we seemed even stronger afterwards. Like a resurrection.

Your stepfather was even more of a child than you. More of an embarrassment. Your poor mum. Sometimes she found him sleeping in the sandpit, in the middle of kids playing. It could be lunchtime, on a weekday. At least you didn’t do that, you told me with conviction. I didn’t know what to say, so I kept quiet. It happened more and more that I kept quiet. Until there was no turning back. One day I had lost the ability to speak. (Or I thought I had lost it, so I didn’t even try. There wasn’t much to say either.) But that was later, towards the end.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

*

‘Did I ever tell you that I only have thirty percent sight in one eye, and less than twenty in the other?’ you asked me while driving 140 km/h on the highway in the middle of the night in January. I was half asleep but woke at once. ‘No, you didn’t.’ You were quick to add that you had gotten so used to it, since you lost your real glasses years ago, it didn’t really bother you anymore. I squinted my eyes and tried to imagine what such a sight looked like, the actual view, from inside. Thirty percent together with less than twenty – it seemed a bit worrying, especially at nighttime. On the other hand, there were definitely things in our lives that were far more worrying and, in some weird logic, thinking of that made me relax again.

People stored all kinds of stuff in their cellars. It was often exciting just to see – you never knew what you were going to find. And we often forgot what we were looking for. Not that we knew, but it had to have some kind of value and be possible to sell or trade to be worth the risk – to be smart. We were mostly far too tired to be smart. Or mesmerized by whatever we happened to stumble upon that made us forget about ourselves for a moment.

‘What about this one then?’ I shouted through the metal bars and burst into a laugh that made me cry so heavily I almost lost my breath. ‘Sssssshhhhhh!’ you answered with your index finger pressed against your lips as you turned around. ‘Please’, you begged, but it was too late. Once I had started to laugh like that, there was no point in trying to make me stop. It usually just made it worse. ‘We could get married in the summer!’ I managed to continue before losing my breath again. I had never tried on a real wedding dress before, so I thought it was a big thing. But you weren’t impressed.

The third summer (it must have been), you were determined to teach me how to drive. It wasn’t sustainable to live in a car and not be able to drive it. I agreed. We drove out to the countryside. It was mid-July, so many people were on holiday. The first hour was thrilling, but your support was a little exaggerated, so my confidence rose too quickly. Suddenly, we were stuck in a trench and couldn’t get out. I blamed the sun: ‘I was blinded, see?’ When night fell and we still hadn’t moved, we packed our things, left the car and took another one nearby that wasn’t even locked. You forced me to drive it back to town and, from that day on, I drove. You didn’t give me any more lessons and I never asked for them either.

Apart from the car, or the cars, there were also the communal laundry houses around the city. They were plentiful and undoubtedly the best in many ways, so we made sure we could get access to them. It wasn’t that hard. I recall one time particularly clearly, and that’s where the picture of you that I mentioned first came from. We were not in good shape, yet in a good mood given the circumstances. Watching you from a distance while carefully folding our clean clothes, I truly believed (for a moment) that we were living ordinary lives. Doing ordinary stuff. Taking care of ourselves and our belongings. The illusion made my eyes tear up.

At times, our union became unbalanced. Like when one of us came back after a stay at some institution and the other one had remained on the streets all the time. Balance was a life necessity. As if the situation itself was a physical body that demanded the total weight of us within its skin, in order to move. Any imbalance was usually gone after a week or so, and we quickly forgot it had ever existed. Until the next time. And most of our fights – which were surprisingly few, considering the limited space in the car – took place at such times.

At the treatment centre, they gave us different tasks every Monday to be completed by the end of the week or daily, depending on the task. They were not so advanced. I guess they didn’t want us to feel stupid. But being treated like a child doesn’t feel very good either. That was certainly a mistake in the pedagogics – though it was true that many of us had acquired some form of brain damage, and it was far too early to say what was temporary and what wasn’t. The tasks were supposed to prepare us for this new life, outside. As if it was a caring friend, who stood there waiting for us with open arms.

One of the tasks was to write notes on small pieces of paper and paste them on the bathroom mirror. The only requirement was that they should be something positive and (preferably) urging. They gave some examples: Today I will love myself. Today I will not think about the past nor the future but only exist in the moment. I am free to live the life I choose. Everything is possible if I just want it enough. All my acts shall reflect the unique and wonderful person I am!

I felt so dirty. I showered three times a day but still didn’t feel clean. I could have stayed in the shower for the whole day if they had let me. ‘It’s just psychological’, they kept repeating in the most arrogant way. ‘It’s only in your head!’ How could they know? They acted as if they knew everything and I had never liked that kind of attitude, especially not from institutional people. They were just scared of their own emotions and had to project them onto us to feel secure themselves. They got paid for it as well. And had the keys to our rooms. And documented every move we made. Or didn’t make.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

*

The first twenty-four hours of freedom are always the worst. (One has to know that.) Last time, I was placed in a foreign city. They called it a fresh chapter and gave me a jacket big enough to fit two of me. The shoes were also theirs – the smallest they had, which were two sizes above mine. I had to hurry to the grocery store before it got dark so I wouldn’t get lost. Once in there, I was really lost. Lap after lap in the strong spotlights for nearly an hour, until I got so stressed I just grabbed some random groceries. One thing was super expensive, but I just paid for it to get out. It never struck me that I had the right to change my mind.

The first year or two (of this new era that you were not a part of), I found myself in a constant feeling of shock, for being alive. I was surprised every morning, that I could move my arms, that I could raise myself from bed, that my body just functioned – all by itself. I feared it would end at any time, but it didn’t. It continued. I wanted to call you to tell you about it but didn’t. Just decided to postpone it. Until I was really sure.

When the physical side had settled, there was another shock as well: not only I but society had changed. I was lost and confused in this new existence, and was told it was good to find a new identity as soon as possible. It would increase my chances significantly. I tried to remember what I had used to like before, when I was younger. I asked my mum, who brought me my old camera equipment, which had been kept in her basement for nearly a decade. I was truly hopeful at first but soon found that everything I knew about photography was useless. It was all digital now.

The people at the employment centre looked at me like I was either joking, or provoking, when I said that I didn’t have an email address and didn’t know where to go to get one. It was no joke. As I stood there in my new clothes, all soaked in sweat and my heart beating violently, I had never been more serious in my life. I wanted to cry but quickly turned the feeling into disregard. What was wrong with pen and paper? If they only knew how many letters I had written. I didn’t want their jobs anyway.

Little by little, it dawned on me that the changes I had begun to detect around me were not just some small random changes. Rather, it became clear that something very big had taken place. All in a period of a few years. Yet those years had happened to coincide with the very ones I had been away. And by the time I came back, the world I had left no longer existed. The tiny fragile hope for myself, which had just started to sprout in me, was lost the moment the immense insight struck me: I had missed the digitalization of society.

Image courtesy of Petronella Petander, still from ‘The Haven’

*

The picture of you (in the laundry house, warm and smiling) kept me focused somehow. Reminded me that there were things of real importance, and that anxiety about an art project was not one of them. The picture gave me strength and became a comfort I returned to when needed. It wasn’t really rational, knowing that the time from which it was cut out belonged to those years. Those three years, in the car. Nearly four. The years that were between the time when we first met and the vaguer period of my enigmatic disappearance.

I kept my routines throughout the entire degree programme. It was a commitment I held highly. Every first Sunday of the month, I set the alarm early to drive all the way out to the women’s prison. Many of the women there never got any other visitors. I was thrown back in time, and felt both privileged and rude to be able to walk out through those heavy gates. And the morning after, I went back to uni again, as an art student. It usually took me the rest of the week to adjust and my sleeping needs were like those of a new-born baby.

In the back window of the car, on that little shelf that wasn’t really meant to be used because it could obscure the rearview, you always stored a big pack of START hazelnut granola. A pure security measure: as long as we had that, we would be fine. (It felt so good when you said it, that we would be fine.) Preferably we had it with full-fat milk or yoghurt, but it could go with basically any kind of liquid. In the years that followed (also after you), those cravings kept coming back. Like a default reaction to every feeling of losing control. I would have it for breakfast, lunch and dinner, for weeks. It was just pure sugar and not anything I would normally buy. But every time things started to collapse, it was the only thing I could ever think of eating.

The process with you had its own life, such as sometimes depicted in great literature. The kind of language you think is only metaphoric and beautiful, until it happens to you. Then the poetic changes colour and shimmers in all its range of reality: real, unreal, real unreal. Like wave motions in tides. I was both in it and watched it from the shore. The pictures. The city. You and me, and sometimes others. The summers and the winters. The cars. The car parks and the garage buildings at night. The streetlights. The communal laundry houses. Especially the laundry houses for some reason. I think it had to do with that illusion.

After graduation, I travelled alone to the woods up north to spend time in the old summerhouse my dad had left behind the previous year. I was so exhausted, like I had stumbled across the finishing line just in time before the crash. My plan was to do nothing. Especially not think about art or a possible Master’s programme. (By the way, I hadn’t even decided.) I would just rest for three weeks before going back for my summer job. By the end of the first week, I had started on a new film script. (Though I didn’t know that yet.) The working title of the document was The Laundry House.

*

Every now and then, the car we had at the time was confiscated. It didn’t matter whether the vehicle was legal or not. They just used different paragraphs. The result of the seizure was the same: we lost our home from one day to another and the gravity of the consequences all depended on the time of the year. Summertime, of course, the harm was less, physically and materially. Irrespective of the season, when it happened, we suddenly became much more exposed, in obvious ways but also in ways that were impossible to predict.

I couldn’t walk on the pavement through a residential area without compulsively staring into the windows, with all the potted flowers and curtains, imaging us living there. (In our other, real lives. Like they should have been.) I was fully aware how it annoyed you when I did that – although you did it yourself. When you looked at me, I walked faster, almost jogged, and tried my best to look casual. As if I didn’t care and definitely didn’t have such ridiculous desires.

It happened, not too rarely, that I suddenly lost sense of time. And the more panicked I got when I realized, the more severe it became. Usually, it lasted for hours or days but even weeks when it was at its worst. Sometimes, for example, I didn’t know whether it was a new winter or if it was the same one. What belonged to this year and what was long ago. What was really real and what wasn’t entirely true – I couldn’t tell. There were no outlines of reality any longer, no sharp lines. Or maybe there were, deep under, but we were floating above. Like dead fish, on the surface of the water in an acidic lake.

In the early morning, one late spring, I was woken by a scratching noise and looked out through the front window of the car. The whole vehicle was standing in water. In the lake. The light was strong already, it seemed like another sunny day was about to begin. The scratching sound was you, also standing in the water, scrubbing the car glass in such concentration that you didn’t notice I was awake. You were singing to yourself, that Cher-song: ‘If I could turn back ti-me…’ Softly, I placed my hands on my chest and leaned back in the seat, my eyes still resting on you. I will save this moment, I thought to myself, if not forever, then for a very long time.

The fourth summer, we got to borrow an apartment for free. Or we were told to guard it for someone who was sent to prison. It was in the very centre of one of the more decayed northwestern suburbs. The apartment was situated on the top floor and felt very big. Balcony facing west, two toilets and a walk-in-wardrobe. Two of the three rooms were constantly dark, as the blinds were missing their strings and couldn’t be pulled up. The only furniture was two wheelchairs. When we were too tired or stiff to stand up, we just rolled around, seated. Sometimes we stayed in different rooms, talking to each other on the phone. I guess it felt more private, and we must have been tired of each other’s faces by that point.

You said you were going to quit after the summer. By the way you said it, I understood it was not for me to question or even respond. You had a seriousness I had never seen in you before. Not like that. It made me feel proud, worried and uncomfortable at the same time. Proud, because it was you, taking on such an impossible mission and saying it out loud. Worried, about what that would mean to us. To me. And uncomfortable, because I so wished that I could have taken the chance and just joined you. But I couldn’t. Not then.

*

One of those cold, endless nights – I can’t recall what season it was at the time, even summer nights can be freezing – alone on a stolen bike, with no clue of where I was or where I was going, just searching, like always, carefully scanning the surroundings, hoping to find an opportunity of some kind, I spotted a huge building with a neon-lit sign. A university or art school, the name was familiar somehow. I figured there must be lots of technical equipment inside. In the early dawn – frustrated about the advanced alarm system – I gave up. A few years later, I went back. I was called for an interview. I had applied for the degree programme in Fine Art, and it wasn’t until I entered the building that I realized: I had been here before.

I sat in bed with a thick compendium, one late afternoon as the sun was about to set outside my big window on the seventh floor. The compendium contained a number of reputable texts about art theory. Never had I experienced such academic language – it was an effort to get through and I couldn’t understand half of it. That didn’t bother me at all. I felt completely content in the moment and, as I closed my eyes, I could see myself from above. If anyone had told me this (then), I thought in my quietness, I would have considered that person truly insane.

You sent your condolences through a mutual acquaintance when my mum died, as you did some year later when my dad died. You never got to know how much it meant. How I saved those forwarded messages and read them over and over until, finally, I fell asleep in an early morning haze, with swollen eyes and the phone still in my hand. The agreement to not have any contact was never a choice. It was never a matter of freewill. It was rather a consequence of the decision to try to save my life. I had to remind myself of that every now and then, especially in the period when all these things happened.

I kept writing the text about the laundry house. The whole thing was never meant to be anything. It just came and I had to get it out. There was no thought of it becoming art. After a while, when I started to realize that it might, my first reaction was: ‘No! Not this. Anything but this.’ The feeling of resistance was so strong, almost violent, combined with that paralysing and stinging feeling of shame. I stopped writing it and tried to begin working on other ideas, consciously forcing myself to. After about a week’s crisis, I gave up. ‘Okay then. Damn.’

I struggled a lot with the form, afraid to use the we–form, because the ‘we’ includes the ‘I’. And I didn’t want that. I was so unwilling to let the voice be in first person, that in the middle of the process and halfway into the script, I decided to change it. I tried out different options, but it didn’t work – not without taking something from it. Reluctantly, I had to give up my will and a good deal of pride. If the work itself demanded so, it wouldn’t be right of me to refuse it.

Once I had the first draft of the script, it was time to start filming. I was catsitting for two weeks within walking distance of uni. I had stayed there many times in recent years. It had almost become a second home. That autumn was unusually warm, some kind of record. I enjoyed having company without having to talk. At the end of the street, no more than a hundred meters away, was a big brick building, from the late ’40s or the early ’50s, one of those big laundry houses from back then that are still in use in some suburbs.

‘But why the laundry house?’ I asked myself as the film started to take form, more and more. It wasn’t like we spent all our time in those years doing laundry. That would give a false picture. As if I was trying to cover up all the other stuff, all the things we did when we weren’t in the laundry house. Avoiding the truth. Which (when I thought of it) was exactly what it was all about. The whole thing with the laundry house. The routines, everything. It was just a denial of the reality, outside. We tried to stay inside for as long as we could. In the warmth, in the fantasy. Of course, we did.

The choice of scenery for my film also had a lot to do with that picture, where you stood and folded our clothes. You looked so calm, maybe even happy. Of all the images from our years together, it was that one that kept coming back. In dreams, as in wakefulness. The soft colours, the warmth, your infectious smile. Many times, it took me all the way back there, into the moist heat, with the humming sound from the machines in the background. I guess it felt like a safe place, a way to talk about things that weren’t really possible to talk about.

*

We sat in a ring, tensed, on hard chairs that always made my bum hurt after a while. Exhibition critiques were obligatory. Generally, I found it interesting, but there was something – a kind of unease? – in the air: the fear of saying something stupid or irrelevant, was present in every moment. Additionally – and that was probably what affected my perception of the situation the most – to sit like that, in a circle, reminded me of other circles, in other places. In another time. For a short moment, I forgot what phase in life I was in. Where I was (it was not that kind of building complex). Why I was there (it was not a legal case). What I was doing there (my participation was on a voluntary basis, even though they called it mandatory).