Sexual violence as weapon of war

Sexual violence is being used systematically by the Russian military in Ukraine to achieve the political goals of the Russian leadership, and is not just the result of ‘indiscipline’ or abuse of power.

War-time sexual violence has existed for as long as wars themselves. Memory about mass sexual crimes during World War II still lives – for example, those committed by Wehrmacht and its allies on the occupied territories, by the Imperial Japanese Army (the phenomena of the so-called ‘comfort women’), by the Red Army in Hungary and Germany, etc. Despite the vast scale of those crimes, the post-war tribunals didn’t pay due attention to punishing the guilty, mostly for political reasons and the overall underestimation of the role sexual violence plays in war.

A pivotal shift in international laws regarding this issue happened only in the 1990s. It was the result of trials concerning the genocides in Rwanda and ex-Yugoslavia, where hundreds of thousands of people suffered sexual violence, mostly women and girls. Since then, wartime sexual violence has started to be treated as ‘war crimes’, ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘crimes of genocide’. Wartime sexual crimes began to be characterized as a ‘method’, ‘tool’, ‘weapon’, or ‘tactic’ of war or genocide.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the topic of sexual violence has flooded the media, political, military, human rights advocacy, and research discourses. Their focuses are forms and consequences of sexual violence committed by Russian servicemen in Ukraine. This article focuses on the nature and function of sexual violence, and the question of whether Russia uses sexual violence as a weapon in its war against Ukraine.

Warning: this text contains depictions of sexual violence.

Photo by Karol Szejner via Wikimedia Commons

Challenges of documenting

Because Russian aggression against Ukraine is ongoing, the picture of the crimes committed by Russian soldiers is incomplete. Sexual violence is a part of the large-scale and systematic crimes being perpetrated against the Ukrainian population (according to the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office, more than 71 thousand offences have been committed so far). But unlike the destruction of architectural objects, murders, and injuries which can be seen visually and documented, sexual violence is among the most hidden consequences of the war.

Despite that, information about sexual violence committed by Russian servicemen is now documented by Ukrainian and international human rights organizations, particularly the UN, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the Center for Civil Liberties, JurFem, LaStrada, Women’s Perspectives and others who provide support to the victims. Many publications in foreign media contain interviews with victims themselves. Another important source of information are the intercepted calls of Russian servicemen, which are regularly published by the Ukrainian Security Service. In them, occupiers discuss various crimes committed on Ukrainian territory, including sexual ones.

Data on sexual violence and its perpetrators is also spread by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Prosecutor General’s Office. In particular, they report to Ukrainian society about the number of cases investigated, charges put forward, and first sentences. They also inform about coordination between different state institutions and cooperation with western partners to oppose war-caused sexual violence and help the victims. However, not all officials showed a proper level of responsibility while communicating this sensitive subject.

In April 2022, the former ombudswoman Ludmyla Denisova came under criticism from media workers and NGOs. She was advised to ‘choose every word more carefully and thoroughly’, especially when talking about sexual violence against children, and report about the procedural actions concerning every case publicized. Soon, Denisova was fired from the ombudswoman’s position. That bolstered further speculations about the topic of sexual violence during the war. Both the number of cases voiced by Denisova – she claimed hundreds of incidents back at the beginning of April – and their truthfulness were put in doubt. She found out about most of them from calls on the hotline for psychological help for those who suffered because of the war, created with the support of UNICEF. Denisova explained that she couldn’t pass all information known to her to law enforcement because she didn’t have consent from the victims.

The ‘Denisova case’ demonstrated the challenges Ukrainian society faces with documenting, investigating, and communicating war crimes. The rights and interests of victims and their close ones should be at the centre of these processes. There are human tragedies behind every published case, which is why each one deserves proper attention and checking. Silence and devaluation are precisely Russia’s strategy in its information war against Ukraine. Kremlin politicians and propagandists used the ‘Denisova case’ to undermine all information published by the Ukrainian side concerning sexual crimes committed by Russian servicemen in Ukraine.

The specificity of sexual crimes in Russia’s war against Ukraine

After the occupation of Crimea by Russia and the beginning of the war in Donbas, the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office and police started documenting sexual crimes related to the conflict.1 Between 2014 and 2017, the Eastern Ukrainian centre for civic initiatives collected information about 175 cases of sexual violence against men and women by illegal military formations. It included rape and threats of rape, sexual torture, forced nudity, threats of sexual nature, forced prostitution, threats and attempts at castration, etc. But after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, sexual violence committed by Russian servicemen acquired a different scale, intensity and character.

First, sexual violence became widespread. It is difficult to talk about the exact number of victims. The Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office is currently investigating around 155 cases of sexual violence. And that number is merely the tip of the iceberg in the context of the overall scale of sexual violence, because it includes only cases with clear consent on procedural actions by the victims.

Most victims aren’t willing to testify for various reasons. Some are afraid of stigmatization, victim-blaming and mistrust. Some people want to push painful memories out to avoid traumatizing themselves and their close ones. Some don’t believe in justice. Others are afraid to testify while the war is ongoing because they live in fear of occupiers returning and possible revenge for shedding light on their crimes. Some lack the resources to start a long and exhausting fight for justice. Thus, the number of those who suffered from sexual violence may be not hundreds but thousands, considering how many Ukrainians are now in Russian captivity or on temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

Second, sexual violence has become a tool of terror not against certain groups but against the whole population of the occupied Ukrainian territories. The victims are now not only women and men, but also children and the elderly. After breaking into the home of 75-years old Ludmyla near Kherson, the Russian soldier brutally beat and raped her. Another 83-year-old woman was raped by a Russian soldier in front of her husband, bedridden due to an illness.

According to the UN data, the youngest currently known victim is only four years old. Instances of gang-raping girls aged 9 to 11 are known in Bucha, Kyiv region. It’s also known from the talks among the Russian military, intercepted by the Ukrainian Security Service, that 10 of their soldiers raped a 12-year-old girl in the Luhansk region, and three others – a 16-year-old girl. Among the victims, there are also boys, particularly an 11-year-old, raped in front of his mother.

Third, sexual crimes are committed with outstanding and demonstrative cruelty. This is evidenced not only by the age of the victims and the presence of the members of vulnerable groups among them – children or the elderly – but also by the dynamics and manifestations of that violence. In many cases, it is not a brief act but may go on for hours, days or weeks, taking the form of sexual torture to satisfy the aggressor. It is especially typical for sexual violence in places of forced detention.

The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine documented in its report the testimony of a man who was kept near Olenivka in the Donetsk region. He stressed that occupiers attached wires to his genitalia and nose: ‘They simply had fun and were not interested in my replies to their questions.’ Victoria, 42-years-old from Kyiv region, was raped all night long, despite begging her attackers to let her go. It’s also typical that men are murdered who try to defend their wives – along with the raped women themselves. Some victims had their teeth knocked out, hair cut off, limbs broken, face and neck cut, fingernails torn out. A separate kind of cruelty is raping children in front of their parents and vice versa.

This is enough to affirm that sexual violence committed by Russian servicemen has features of a weapon in the war against Ukraine.

Carnival of violence

Sexual violence by Russian soldiers should be viewed not as a separate phenomenon but as part of the wide repertoire of violence against the civilian population on occupied Ukrainian territories. Sexual violence is one way to demonstrate authority, to terrorize, humiliate, intimidate, and demoralize the ‘enemy’, and to reduce their will to resist. That’s why it takes grotesque and demonstrative forms.

Perpetrators act in ways that make the victims realize the meaning of the violence for their torturers. The perpetrators’ vocabulary, for example, underlines the political significance of violence. Victims are let know that they have been targeted because of their political views, their Ukrainian national identity, or their relatives’ affiliation with the Ukrainian military or governmental institutions. For instance, on 3 April 2022 a mother of four in the Kherson region was raped for 12 hours by two Russian soldiers, who called her a ‘Banderite’, possibly because her husband was serving in Ukrainian Armed Forces at the time.

According to Iryna Didenko, a prosecutor in the Prosecutor General’s Office, there are known instances of Russian occupiers purposefully targeting wives of Ukrainian servicemen, possibly to try to undermine their morale and masculinity. Another demonstrative form of sexualized violence was shaving the heads of Ukrainian servicewomen. One of them, Anastasia, recalled: ‘They made us undress fully and squat in the presence of men. Shaved us bald.’ Pictures of the women released from Russian captivity on 2 April 2022 shocked not only their relatives and colleagues. Visual marks of torture committed against them were of a message to the Ukrainian community in general about the values and intents of the enemy, which shuns no methods to achieve its goal.

Sexual violence of Russian servicemen against LGBT+ people in Ukraine also has a political tone. It is motivated not only by the homophobia of particular soldiers but possibly also by the aggressive anti-gender rhetoric and policies of Putin’s Russia in recent years. Kremlin propaganda pictures Ukraine as ‘a testing ground for unnatural phenomena’ and ‘satanism’, against which Russia is ‘forced’ to wage a ‘spiritual’ and righteous war.

As a result, Russian soldiers don’t conceal their enmity towards people with non-traditional sexual orientation in the occupied territories of Ukraine, and use rape as a way to punish and humiliate them. This is evidenced by the ‘LGBTQ and the war’ report, prepared by the ‘Our World’ centre in November 2022. One of the victims recalls that two Russian soldiers broke into her home in the Kherson region during the night: ‘Are you those “pinks”? though there was no pretext besides the fact that K. looks masculine. We were raped – me and my girlfriend – with the use of physical force.’ Another part of the report mentions that after finding out about the homosexuality of a 31-year-old man in Mariupol, occupiers sent him to the penitentiary in Olenivka, Donetsk region. They disclosed information about his sexual orientation there, and because of that, he suffered multiple cases of sexual violence.

A characteristic feature of Russian occupiers’ sexual crimes is that they ‘need’ the public to maximize the harm. This is what distinguishes wartime sexual violence from that committed in times of peace, where it’s usually done secretly to conceal the crime and thus to avoid responsibility. Criminals often don’t think about responsibility in the occupied territories. They are interested foremost in asserting their power and achieving both personal and military-political goals. This is why violence takes public forms and happens in the presence of relatives, friends, neighbours or other people who are with the victim in a shelter or places of detention.

The presence of witnesses, especially close friends and relatives, causes the victim additional suffering and time traumatizes eyewitnesses, because usually they aren’t able to help. They are made to observe the torture silently and helplessly. As a result, witnesses become victims themselves and may live through trauma, similar in intensity and symptoms to the trauma of the so-called ‘primary’ victims. For example, a boy aged 6 from Mariupol, whose mother was raped in front of him, went grey-haired; and a 15-year-old who watched violence against his mother had suicidal thoughts.

Sexual violence and military goals

Sexual violence becomes a tool of war when it serves the tactical and/or strategic interests of a fighting army, rather than just the individual interests of particular soldiers; in other words, when it is not just the result of a lack of discipline, but a factor intended by the aggressor to bring the achievement of military-political goals closer.

Commanders are aware that their subordinates commit sexual violence on occupied territories against the civilian population or prisoners of war, but don’t oppose it effectively. They don’t implement preventive enlightenment or disciplinary action, and they don’t punish the perpetrators properly. Wayne Jordash, a British lawyer who consults Ukrainian prosecutors, stated that he saw the signs of commanders’ acquiescence in 30 cases he had reviewed.

In some cases, commanders organized rape themselves. That happened with 42-year-old Victoria from the Kyiv region. She recalls that among three soldiers who knocked on her door during the night, there was a commander. He ordered the woman to go with them, explaining: ‘Our boys have had some drinks and they want to relax.’

Some commanders try to use sexual violence as kind of a reward for their soldiers, a way to encourage them and boost their morale, especially with poorly motivated soldiers like the mobilized ones. At the same time, sexual violence may be perceived by commanders as an acceptable and ‘safe’ way to channel soldiers’ rage and frustration caused by defeats on the battlefield and unhappiness with the conditions of service.

Hence, it’s not a coincidence that Russian soldiers committed many crimes against civilians when retreating from territories such as Lyman in the Donetsk region. Gang rape also acts as a tool to form cohesion and collective values in the army – a shared experience of crimes as something that brings soldiers closer. Considering that many people who ended up in the Russian army, especially since the start of mobilization in September 2022, didn’t previously know much about the war and probably didn’t plan to participate in it, sexual violence (as well as other crimes) might be a form of ritual for military socialization.

Gang rape as a way to form fraternity among Russian soldiers can be seen in the memories of a man who witnessed rapes in Irpin:

I didn’t hear anyone order this, but also, no one tried to stop them. On the contrary, they were encouraging each other; it was a joke to them. They were speaking Russian so we could understand them. I can’t remember the exact words, but I remember it meaning something like ‘our senior command allows us to do whatever we want unless you go to Bucha, because no one is waiting for you in Bucha.’ I still don’t know exactly what that meant, but I can presume they belonged to a unit that was headquartered there but was coming to Irpin to act like this.

According to the witness, soldiers stripped, beat and raped women. They killed four of them and ordered the eyewitness to put their bodies in a truck, which they later set on fire.

Commanders may encourage sexual crimes in order to scare and demoralize the opponent. Illustrative in this respect was the video of the castration and killing of a Ukrainian prisoner of war, published on Russian social media on 28 July 2022, probably committed by 29 year-old Ocur Suge-Mongush from Tuva. According to investigators from the Bellingcat and Conflict Intelligence Team, the same criminal belongs to the Chechen group ‘Akhmat’ and appears in various propaganda videos.

After the publication of the video of castration, which has the characteristics of a war crime, there were no statements by the Russian military command assessing the actions of the executor and his partner, who was filming. Neither the Russian military prosecutor’s office, nor any other institution or politician made a statement about an opened criminal proceeding. According to the probable perpetrator himself, FSB released him after two days of investigation, saying that everybody depicted on video, executor of the crime included, were ‘Ukrainian soldiers’.

In other cases, the Russian authorities not only protect their soldiers from criminal prosecution for war crimes in the occupied territories of Ukraine but also openly reward them, which simultaneously serves as an encouragement for new crimes, particularly for other military units. That happened with the 64th motorized brigade stationed in Bucha, which became notorious for multiple instances of sexual violence, even against children. By Putin’s decree of 18 April 2022, it received an honorary guards status for ‘mass heroism and honor, firmness, and bravery’.

‘That’s a lie’: official Russian discourse

From the moment when first accounts about rapes started circulating, Russian officials started denying everything. ‘We strongly refute it’, said Putin’s press secretary Dmitri Peskov on 1 March 2022, reacting to the statement by the International Criminal Law about the Russian army’s war crimes in Ukraine. A few weeks later, he claimed, ‘We don’t believe the information [of Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office] about raped women at all. That’s a lie.’

On the international stage as well, Russian officials categorically deny that Russian soldiers committed sexual crimes in Ukraine. For example, at the UN meeting about the situation in Ukraine on 4 April 2022, a Russian representative claimed that such information was spread to ‘distort facts and discredit the special military operation’.

Another UN meeting on 6 June 2022 started with a report by Pramila Patten, Special UN Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict. She talked about 124 cases of sexual violence related to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In response, the Russian representative Vasily Nebenzya claimed there was ‘no proof’ to support such accusations, which were the ‘favourite tactic of the Kyiv regime and its western colleagues’. When Patten published information that Russian soldiers use Viagra during rapes, the Russian Ministry of foreign affairs released an official ‘refutation’, voiced by Maria Zakharova. According to Zakharova, such claims were ‘a perverted fantasy’, and they are ‘impossible to comment on seriously’.

We can see similar rhetoric of absolute denial of sexual crimes committed by the Russian army in Ukraine in Russian media space. In June 2022, the propagandist Olga Skabeeva, in her talk show ‘60 minutes’ on the central Russian channel ‘Russia’, said that ‘it’s known for a fact that nobody raped anybody. In any case, not a single person accusing Russian soldiers of that has voiced neither name, nor surname, nor place of the event, nor time of the rape.’

The host probably knew that the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office had already transferred to court the case of the rape of a woman. The suspect was Mikhail Romanov, a serviceman of the 239th regiment of 90th tank division of Russian armed forces.

Other Russian media people also stick to the official ‘lack of proof’ version. Vladimir Solovyov, the Kremlin’s top propagandist, wrote in his Telegram channel on 4 May 2022 that ‘informational henchmen of the Banderites are hyping an old “myth” about the Russian army being rapists’. In Solovyov’s view, it was nothing else than a reanimation of the ‘Goebbels propaganda’ that ‘appeared in Nazi Germany near the end of the war’ about Russian soldiers raping all German women aged between 8 and 80.

Solovyov drew parallels between the ‘fictional’ sexual crimes of Russian soldiers in 1945 with those of the Russian army in Ukraine now. In his desire to convince the audience of the falsehood of accusations against Russian soldiers then and now, the Kremlin propagandist resorted to the denial of one of the most documented and researched sexual crimes in the history of warfare, namely those committed by the Red Army in occupied Germany. According to Antony Beevor’s research, about 100 thousand women were subjected to sexual violence by the Red army soldiers in Berlin alone; 10 thousand of them died, mostly by suicide.

Sexual violence by the Russian military in Ukraine after the start of the full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022 isn’t just a ‘by-product’, the result of bad discipline, low morale, or abuse of power by individual soldiers and officers. Its systematicity, scale, organization and forms prove the conscious and deliberate use of sexual violence to achieve the military-political goals of the Russian leadership. That is why investigating and punishing the guilty should be a priority not just for Ukraine but also for international institutions, to help the victims, and achieve justice and durable peace.

The perpetrators were on both sides of the conflict, for example, members of the dissolved Ministry of Internal Affairs ‘Tornado’ company, some of whom were sentenced for rape. The UN pointed to the instances of sexual violence used by Ukrainian law enforcement employees against detainees in Donbas.

Published 14 March 2023

Original in Ukrainian

Translated by

Yuriy Chernata

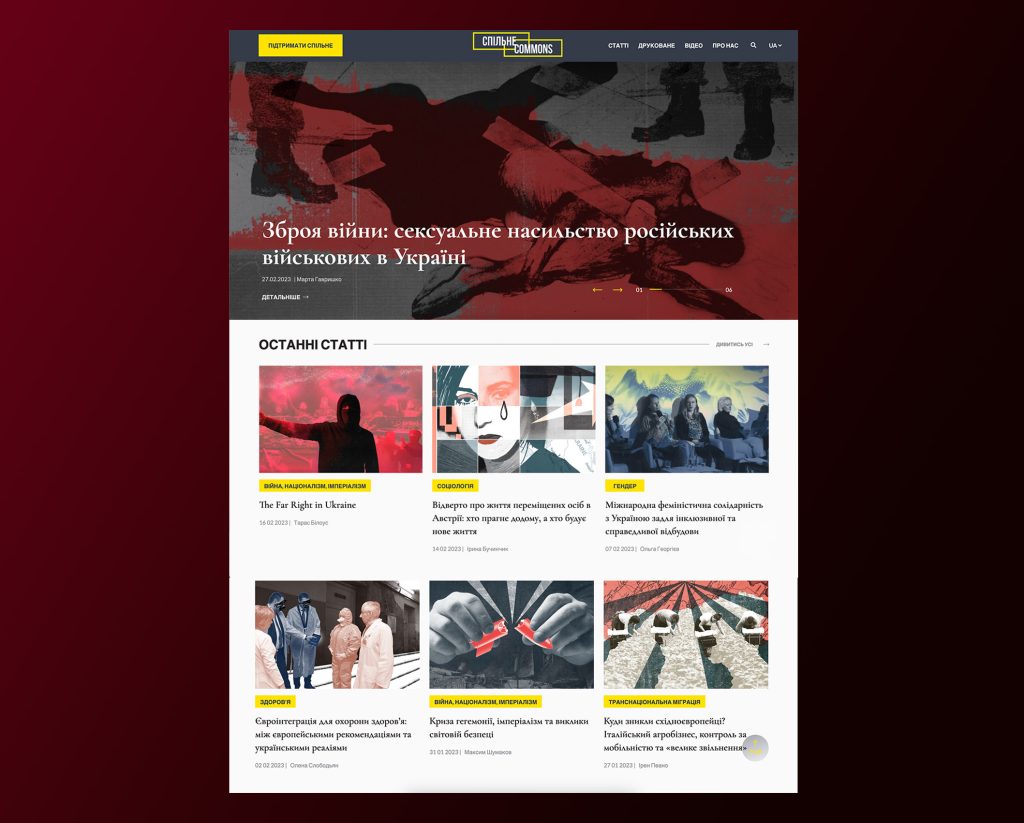

First published by Spilne

Contributed by Spilne © Marta Havryshko / Spilne

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The ‘Trump–Putin deal’ again places Ukrainians in a subaltern role. The leaked contract with its fantasy $500 billion ‘payback’ has been compared to Versailles, but the US betrayal recalls nothing so much as Molotov–Ribbentrop.

Ukraine faces its greatest diplomatic challenge yet, as the Trump administration succumbs to disinformation and blames them for the Russian aggression. How can they navigate the storm?