Sex work is work. That’s the problem… and the key

‘Sex work will disappear the day we abolish capitalism. Until then, let’s talk about labour rights.’ Amaranta Heredia Jaén calls to address the controversial results of anti-trafficking measures.

This is not a neutral piece. But what piece on sex work is neutral? Beware of those who claim to be neutral, because few debates are more heated than those on this topic. I believe feminists – and all those people striving for a greater social justice – should support sex workers. This is an urgent matter.

All over the world, more and more people are struggling with poverty, becoming homeless, being deported, harassed and raped, and dying as a direct or indirect consequence of anti-prostitution policies and initiatives dressed as anti-trafficking campaigns. The war on trafficking and – due to the widespread conflation – sex work is raging, and the consequences are devastating.

This article explores the rationale and the consequences of the anti-trafficking industrial complex – as it has been called1 — and the rescue industry.2

While some respected international organizations have started agreeing on the decriminalization of sex work in order to secure human rights and fight poverty, more and more countries are criminalizing sex work and disguising border control and anti-immigration policies as anti-trafficking measures.

Why work

‘Sex work’ is the term chosen by sex workers to refer to the labour they perform, with the clear intention to emphasise that it is ‘work’ and to avoid the moral judgments associated with the term ‘prostitution’. Sex work can be considered part of the service industry, which is often undervalued, unwaged and feminized. Keith Hart3 suggests that one of the ‘sins’ of sex work is to take something from the private space, where it is not financially remunerated, and make it public and monetize it.

Sex workers could be seen to embody Silvia Federici’s cry for ‘Wages for Housework!’ by monetizing one of the services women are traditionally expected to offer for free within the household.

Photo source: Jean Koulev on Flickr

Sex work includes a wide range of services. Whether they do cam work, phone sex, street-based work, or porn, sex work activists use this umbrella term to show solidarity, counteract the whorearchy4 and convey a sense of professionalism.

After all, ‘sex worker’ would be a ridiculous slur, whereas everyone knows the many synonyms that are used as insults in our very sex-negative languages. It is also hard to imagine an anti-trafficking rescue team raiding a brothel to ‘rescue’ a professional dominatrix.Of course, neo-abolitionists – who consider selling sex as inherently oppressive and sex workers as victims – use a very different language. And words matter.5 The use of the term ‘prostituted woman’ is typical of most neo-abolitionist or SWERF6 texts.

The three common legal frameworks that regulate sex work are often conflated and misunderstood: criminalization, legalization and decriminalization.7

Criminalization is still the prevailing legal framework in many countries, where selling sexual services of any kind is deemed illegal and the person providing them – and usually also the client and third parties – can be prosecuted, resulting in fines, imprisonment and deportation, as well as in stigma, harassment, abuse and rape. This creates countless problems for sex workers, who are forced to work outside of the social security system, lack access to health services, recourse to the authorities in case of being the victim of a crime, and so on. Not only are they victims of violence from clients, they also suffer harassment and rape from state authorities. Sex workers who face criminalisation and repressive policing are more likely to experience violence and poor health and wellbeing.8

Due to the adverse effects of criminalization on the lives of sex workers, some states have implemented the model of partial criminalization – also known as the Swedish model – or legalization.

The Swedish or Nordic model was first implemented in 1999 and is spreading rapidly. Within Europe, it has been introduced in Ireland, Northern Ireland, France, Canada, Israel, Norway and Sweden. It decriminalizes the selling of sexual services, yet criminalizes the buying (clients) and facilitation of sex work (third parties). It is often said to be the most effective way to reduce prostitution while protecting women, whom it frames as victims. A vast body of reports have been published on the problems with this approach.9 In fact, it does not help sex workers. It still renders their work highly dangerous and forces them underground. It puts them at high risk of becoming homeless or being blackmailed by their lessor (who could be charged with pimping). They are also put at risk of being prosecuted themselves when they work or live together, since they can be accused of ‘pimping’ each other. Neither can they hire a secretary or security services.

There are other ways

Two other models – ‘decriminalization’ and ‘legalization’ – are often used interchangeably, despite important differences in meaning.

Legalization involves various forms of state control over sex work through regulations that are usually much greater than the control over most other categories of employment. This often results in the marginalization of vulnerable people. These controls might vary, but they typically include registration, regular compulsory health tests and the designation of potential work areas (outside of which sex work is illegal). These requirements mean that many sex workers are still criminalized, since they fail to fulfil the sometimes impossible requirements.

In the Netherlands, migrants are not deemed eligible for sex work licenses, which forces them into illegality. In Nevada10 sex workers are only allowed to work in licensed brothels, must undergo compulsory weekly STD testing, can be convicted for felony if they are HIV-positive, and are often required to live on the compound of the brothel and pay the owners between 40–50 percent of their earnings, on top of room and board expenses. Many of the conditions imposed on sex workers within the legalization framework are deemed to controvert human rights and civil liberties, and workers are often subjected to poor or abusive working conditions.

It is very important to point out that no single measure will eradicate violence and abuses against sex workers. The model sex workers advocate is full decriminalization. This means that no one can be arrested or criminalized for selling, purchasing or facilitating sexual services.11 Here, sex workers can work as freelancers, be hired by someone else or join a cooperative. They can also access social security benefits, including health insurance. This human rights-centred approach (as opposed to crime-focused approaches) allows for the development of measures that increase the wellbeing of sex workers and reduce violence against them, both from clients and the authorities.

Legalization creates narrow regulatory regimes based on concerns and objectives such as the health of clients, taxation, or public morality; decriminalization, on the other hand, means the removal of criminal and administrative penalties that apply to sex work, allowing it to be governed by labour laws and protections, similarly to other jobs.12

Amnesty International (AI)13 and the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW)14 are two international organizations focusing on human rights15 that, having undertaken extensive research16 are now supporting decriminalization. Like all groups or organizations that support decriminalization, they have to be wary of false dichotomies and a handful of myths.

Despite regular accusations, none of these organizations supports the trafficking or enslavement of people. AI, GAATW and sex workers-led organizations want to end to trafficking, however not at the cost of the human rights, let alone the lives of sex workers. The principle of ‘do no harm’ means that, in order to protect a group of vulnerable individuals (i.e. trafficked people), one cannot violate the rights of another vulnerable group (i.e. sex workers).

Sex wars

Though it may be hard to believe for the average citizen who has been bombarded with anti-(sex-) trafficking propaganda, most trafficked people are not enslaved in the sex industry. There are, by the best estimates, 40.3 million people worldwide forced into labour in unacceptable conditions.17 Of these, around 90 per cent are forced into occupations such as construction, farming, mining, manufacturing and domestic work. However, to our knowledge, there are no groups working for the abolition of all types of domestic work, despite the high rates of abuse and exploitation proven to exist in the sector. Anti-(sex-) trafficking18 measures are not, therefore, about stopping exploitation, as Nandita Sharma and Kamala Kempadoo, for example, have pointed out.19 As state policies, they are about border and immigration control, and for feminists groups about the abolition of prostitution.

What has been labelled ‘the feminist sex wars’ is in fact a political divide. With the exception of those who take the proposal that all penetration is rape to its logical conclusion and refuse to engage in any form of it,20 most feminists who oppose sex work hold dear a moral hierarchy of sexual interactions – most often favouring the types long ago described by Gayle Rubin as heterosexual, reproductive, non-commercial, monogamous, coupled, vanilla and domestic.21 They see sex work as inherently degrading; a considerable volume of articles approach this topic from a patronizing perspective, detailing the possibilities of a middle-class white woman imagining herself spreading her legs, being penetrated and getting paid for it.22

However, if one acknowledges the tyranny of patriarchy and the oppression of women, it is not even relevant whether one finds sex work degrading or not. Instead, one can rather focus on what really helps sex workers: decriminalization, harm-reduction and anti-poverty measures. Even if one believes no one would ever choose sex work willingly, one can still invest one’s efforts and resources in creating alternatives, instead of criminalizing or persecuting sex workers.

Anti-trafficking campaigns do not talk about the ‘collateral damage’23 – the abuses – of the rescue industry. The consequences of current anti-(sex-)trafficking measures are varied and highly problematic: from the diverting of funding to an increase in harassment and rape by the police, to forced labour, imprisonment and border control.24 These measures often increase sex workers’ chances of being abused, exploited and even trafficked – this time for real.

Sex trafficking exists. And yet awareness campaigns still can be detrimental. They distort the reality in order to grab people’s attention – and donations. They promote sensationalist media coverage25 and feed mass hysteria. They tend to focus exclusively on sex trafficking, ignoring the vast majority of human trafficking that takes place nowadays. They conflate sex trafficking with sex work and increase public and governmental support for anti-trafficking laws which harm sex workers, fail to support trafficked people, and instead are used for border and migration control. The diversion of funds to these rescue campaigns is very harmful, since this funding could be used to support initiatives that improve the living conditions of sex workers and other vulnerable communities.

Industrial complex

The rescue industry involves the police, sometimes accompanied by NGOs, who raid brothels or areas of street-based workers and detain everyone in the search for victims of trafficking. Very often, people are detained based on their appearance – a leeway for racial profiling. Often, women are charged simply for possessing condoms,26 which in some parts of the world has driven sex workers to engage in unsafe sex practices. The extreme misogyny in the assumption that a female carrying condoms in public is necessarily a sex worker needs to be emphasized here. Raids and rescue operations deprive sex workers of their autonomy, income and secure working conditions.

In Cambodia, where the situation has run havoc, arrested sex workers are placed in rehabilitation centres and are forced to stay in shelters and work for free or for the minimum wage in the garment industry.27 This is very same industry that many sex workers try to escape in the first place. Salaries in the garment industry are $61 per month, the minimum wage, and not enough to support a family, whereas an average income in sex work brings in between $120 and $180 per month. The conditions in the ‘rehabilitation’ centres are often similar to those in detention.28

The ‘unintended consequences’ of criminalization also include police harassment, all the way up to rape. Police are not trained in outreach work and are often violent. A decriminalized framework, on the other hand, allows sex workers to build trusted relationships with state authorities and NGOs and report violence from clients, abuses from employers or the police.29

Anti-trafficking policies are also used for border and migration control.30 The main priority of most governments is to limit migration, rather than to protect migrants against abuse or exploitation; and to prosecution of traffickers, rather than to safeguard the rights of the people who have been trafficked. People suspected of intending to engage in sex work are often denied visas,31 which is again normally based on their appearance and the prejudice of the official dealing with their case. Deportations32 are dressed up as ‘helping the victims return home’. These cases go unnoticed and uncontested. Trafficked people should undoubtedly be offered the possibility of returning; but after the suffering they have endured, they might also want some sort of legal status in the state that might have been their preferred destination in the first place.

Obviously, sex trafficking exists. Its victims obviously need support. Sex workers are in a unique position to identify victims of sex trafficking, to reach out to them, to understand the nuances and difficulties of their situations, and to offer solidarity. They are already doing this.33

Fighting trafficking – all sorts of trafficking – and supporting workers – including sex workers – are not mutually exclusive. It is not fast, nor simple; it is not sexy, and it does not rely on the police. It will not be a right-wing initiative. It is as hard as it is pressing to support those who never benefited from the basic protections of social security, trade unions and labour rights.

Hart, Keith (2000). The Market from a Humanist Point of View. In The Memory Bank: Money in an Unequal World (pp. 170-223). Profile Books.

As phrased by Tilly Lawless: ‘The whorearchy is the hierarchy that shouldn’t – but does – exist in the sex industry, which makes some jobs within it more stigmatized than others, and some more acceptable. Basically it goes like this, starting from the bottom (in society’s mind): street based sex worker, brothel worker, rub and tug worker/erotic masseuse, escort, stripper, porn star, BDSM mistress, cam girl, phone sex worker then finishing with sugar baby on the top.” Sciortino, Karley (2006, May 23). Sex worker and activist, Tilly Lawless, explains the whorearchy. Interview for Slutever. See: https://slutever.com/sex-worker-tilly-lawless-interview/

Lister, Kate (2017, October 5). Sex workers or prostitutes? Why words matter. iNews. The Essential Daily Briefing. Retrieved from https://inews.co.uk/opinion/columnists/sex-workers-prostitutes-words-matter/

SWERF is the acronym for ‘Sex worker exclusionary radical feminism,’ a strand of feminism characterized by whorephobia and hostility to the third wave of feminism. It is not considered radical or even feminist by the standards other feminist groups.

For a good summary of the different models, their goals, impact and evaluation following the SWEAT test, check: Sex Rights Africa Network (n.d.). An Easy Guide to Sex Work Law Reform: The difference between criminalisation, decriminalisation, legalisation and regulation of sex work. Retrieved from https://www.sexrightsafrica.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Sex-work-reform-120919guide.pdf

The SWEAT test evaluates legislation regulating sex work according to the following parameters:

Safe from police abuse: can sex workers work without fear of police abuse?

Workers’ rights: are the labor rights of those in the industry protected full?

Exit: can sex workers leave the sex industry of their own free will without fear of prejudice?

Access to health care: can sex workers access respectful health care services?

Trafficking and sexual exploitation of children: can sex workers report crimes like trafficking and child exploitation without fear?

For a comprised summary see: the infographics of ICRSE.

Platt, L., Grenfell, P., Meiksin, R., Elmes, J., Sherman, S.G., Sanders, T., Mwangi, P., & Crago, A.-L. (2018). Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoSMed 15(12) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002680

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: Criminalisation and repressive policing of sex work linked to increased risk of violence, HIV and sexually transmitted infections Research report 2018.12.11. https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/news/2018/criminalisation-and-repressive-policing-sex-work-linked-increased-risk

Check, for example, the following advocacy toolkit by NSWP or the report on the situation in Norway by Amnesty International:

Global Network of Sex Work Projects, NSWP (2014–2015). The Real Impact of the Swedish Model on Sex Workers. Advocacy Toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/The%20Real%20Impact%20of%20the%20Swedish%20Model%20on%20Sex%20Workers%20Advocacy%20Toolkit%2C%20NSWP%20-%20November%202015.pdf

Amnesty International (2016): The Human Cost of ‘Crushing the Market’. Criminalization of sex work in Norway. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/EUR3640342016ENGLISH.PDF

Hindle, Karen; Barnett, Laura, & Casavant, Lyne (2003). Prostitution: A Review of Legislation in Selected Countries. Legal and Legislative Affairs Division (PRB 03-29E Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Canada). Retrieved from https://lop.parl.ca/content/lop/ResearchPublications/prb0329-e.pdf

States that support the decriminalization model of sex work still prosecute anyone who buys sexual services from an underage person or a person under the age of sexual consent, but this falls into the realm of laws against child sexual abuse.

SWOP Behind Bars (n.d.). Sex Work and Sex Trafficking. In SWOP Behind Bars. Retrieved from https://swopbehindbars.org/amnesty-international-policy-to-decriminalize-sex-work/the-difference-between-sex-work-and-sex-trafficking/

A good example of this is the Guide developed by the Occupational Safety and Health Service of New Zealand after the Prostitution Reform Bill was passed into law on 27 June 2003. This document sets standards for worker-employer relationships, among other areas:

Occupational Safety and Health Service (2004). A Guide to Occupational Health and Safety in the New Zealand Sex Industry. Retrieved from http://espu-usa.com/espu-ca/wp-content/uploads/2008/02/nz-health-and-safety-handbook.pdf

Amnesty International (26.5.2016). Amnesty international policy on state obligations to respect, protect and fulfill the human rights of sex workers (POL 30/4062/2016). Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/POL3040622016ENGLISH.PDF

GAATW (Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women) (https://www.gaatw.org/) fights for the rights of migrants in a globalized labor market; not to be confused with CATW (Coalition Against Trafficking in Women) (http://www.catwinternational.org), a neo-abolitionist organization working to abolish sex work.

Other renowned international organizations that support full decriminalization of sex work include Global Commission on HIV and the Law, Human Rights Watch, UNAIDS, the World Health Organization.

Amnesty International has published a research summary, as well as four extensive reports into the situation of sex workers in Argentina, Hong Kong, Norway and Papua New Guinea.

Amnesty International: Sex Workers at Risk: A Research Summary On Human Rights Abuses Against Sex Workers' 26.05.2016.

GAATW publishes the Anti-Trafficking Review, a journal that promotes a human rights-based approach to anti-trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights.

The best estimates are by the International Labour Organization, whose definition of modern slavery includes forced labour (state-imposed forced labour, forced labour exploitation by the private sector, forced sexual exploitation of adults, and commercial sexual exploitation of children) and forced marriage. However, the statistics for forced marriage are given separately, accounting for approximately 15.4 million women.

I use the term in this way because, despite of the fact that many of these initiatives are framed as anti-trafficking campaigns, they solely focus on sex trafficking.

See, for example: Sharma, Nandita (2015, March 15). Anti-trafficking: whitewash for anti-immigration programmes. In openDemocracy. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/beyondslavery/nandita-sharma/antitrafficking-whitewash-for-antiimmigration-programmes; Kempadoo, Kamala (2005). Trafficking and Prostitution Reconsidered: New Perspectives on Migration, Sex Work, and Human Rights. London: Routledge; Kempadoo, Kamala & Doezema, Jo (eds.). Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance, and Redefinition. London: Routledge.

N.a. (1981). Love Your Enemy? Debate Between Heterosexual Feminism and Political Lesbianism. Onlywomen Press Ltd.

Rubin, Gayle S. (1984). Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. Retrieved from http://sites.middlebury.edu/sexandsociety/files/2015/01/Rubin-Thinking-Sex.pdf

This prototypical middle-class white woman feels degraded when she imagines herself selling sexual services. Iris Young writes about the dangers of this technique, called ‘symmetrical reciprocity’: ‘When privileged people put themselves in the position of those who are less privileged, the assumptions derived from their privilege often allow them unknowingly to misrepresent the other’s situation.’ In Asymmetrical Reciprocity: On Moral Respect, Wonder and Enlarged Thought. In Constellations 3(3) (1997): 340–363.

Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (2007). Collateral damage. The Impact of Anti-Trafficking Measures on Human Rights around the World. Bangkok: GAATW. Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/microsites/IDM/workshops/ensuring_protection_070909/collateral_damage_gaatw_2007.pdf; SANGRAM (2018). RAIDED: How Anti-trafficking Strategies Increase Sex Workers’ Vulnerability to Exploitative Practices. Retrieved from https://www.sangram.org/resources/RAIDED-E-Book.pdf

For an interesting study of how modern journalism and anti-white slavery campaigns are interlinked, check Soderlund, Gretchen (2013). Sex Trafficking, Scandal, and the Transformation of Journalism, 1885-1917. Illinois: The University of Chicago Press.

PROS Network, & Leigh Tomppert (2012). Public Health CrisisThe Impact of Using Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in New York City. Retrieved from http://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/20120417-public-health-crisis%5B1%5D.pdf

Women’s Network for Unity, & Paula Stromberg: Rights Not Rescue in Cambodia [documentary]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cgPfz9ydEp4

Wijers, Marjan, & Chew, Lin (2010). The RighT Guide. A tool to assess the human rights impact of anti-trafficking laws and policies. Retrieved from http://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/10%20The%20RighT%20guide_ENG.pdf

In the research project Bad Encounter Line, the Young Women’s Empowerment Project tracked violence in the lives of girls in the sex industry. 30 per cent of the reported violent encounters were performed by police, 23 per cent in hospitals and by medical services, 6 per cent by the Department of Children and Family Services, and 1 per cent at shelters. In Torres, Angel, Paz, Naima, & Young Women’s Empowerment Project (2012). Bad Encounter Line. A Participatory Action Research Project. Retrieved from https://ywepchicago.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/bad-encounter-line-report-2012.pdf

Agustín, Laura María (2007). Sex at the Margins. Migration, labour markets and the rescue industry. Illinois: The University of Chicago Press; Miller, R., & Baumeister, S. (2013). Managing Migration: Is border control fundamental to anti-trafficking and anti-smuggling interventions? In Anti-Trafficking Review, 2: 15–3.

For example, in the United States any foreign citizen ‘coming to the United States solely, principally, or incidentally to engage in prostitution, or has engaged in prostitution within 10 years of the date of application for a visa, admission, or adjustment of status’ is ineligible for admission. US Immigration and Nationality Act Section 212 (a) (1) (D) (i). Retrieved from https://www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/SLB/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-29/0-0-0-2006.html

Lam, Elene, & De Lit, Fleur (2016, February 10). Anti-trafficking campaign harms migrant sex workers. Now Toronto. Retrieved from https://nowtoronto.com/news/anti-trafficking-harms-migrant-sex-workers

See, for example, Vollbehr, Wendelijn (2016). Sex workers against human trafficking. Strategies and challenges of sex worker-led organizations in the fight against human trafficking [Master thesis Sociology, University Amsterdam]. Retrieved from http://www.ubvu.vu.nl/pub/fulltext/scripties/26_2113465_0.pdf; SANGRAM & B. Suresh Kumar. Daughter of the Hills. Trafficked and Restored. Sangli: VAMP. Retrieved from https://www.sangram.org/resources/Daughter-Of-The-Hills-Sangram.pdf

Published 23 January 2019

Original in English

First published by Vikerkaar

Contributed by Vikerkaar © Amaranta Heredia Jaén / Vikerkaar / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

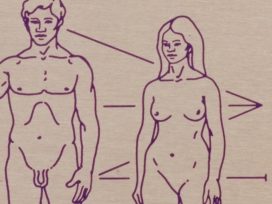

Why was the distinguishing mark of female genitalia erased from NASA’s 1970s image travelling outer space? And will compromised depictions of life on Earth avoid sexist, racist and anthropocentric simplifications by 2036?

While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.