Baltic-German queer

Vikerkaar 3/2024

Queer histories in Estonia(n): featuring 19th-century writing defying heteronormative expectations; why ‘cis-gender’ is a useless concept; Russian-speaking LGBT+ activism; and a history of trans rights in Spain.

Steffen Kverneland describes how the medium of the comic book opens up new approaches to biographies of artists. And how, in his graphic biography of Edward Munch, he lets a little light and air and humour liven up the sad, slightly dull atmosphere that tends to surround the painter.

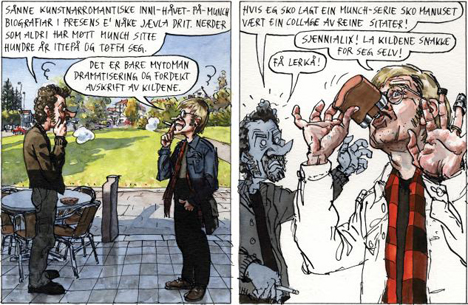

Ever since deciding, seven years ago, to make the life of Edvard Munch into a biographical strip cartoon, my intention all along was to try to get as close as possible to the time in which he lived and to his social group. I wanted the people to come alive; I wanted Munch and Strindberg to speak in their own voices, not the reported speech of the traditional biography. In a sense, I had drawn up a personal Dogme 95-style manifesto: all text must be authentic quotations, and rewrites or additions are strictly forbidden.

Steffen Kverneland at the Eurozine conference in Oslo, December 2013. Photo: Nadine Blanchard

I didn’t know if anyone else had ever “written” biography by cutting and pasting actual quotations, but it struck me as a good idea. My main contribution would in any case be the visual interpretation. The art work would, crucially, be based on my selections and montage, and it was up to me whether the tone was to be humorous or realistic. After all, this was what I had done for years in Amputerte klassikere (“Amputated classics”), so cutting up quotes and creating gratuitous visuals was something I had practised.

Thankfully, there is an enormous choice of written sources. Munch himself was much given to writing and so were his innumerable literate friends. Then, as now, autobiography was fashionable. “Everyone” was keen to write up his or her life story. I had a huge verbal jigsaw to look forward to and meter-long rows of books to read, not to speak of all the drawing that had to be done.

I knew that the task would take years, but not how to go about getting it published. And perhaps even get some regular money in the meantime? Telling the story in instalments would be ideal, but where? In no way could I tolerate some kind of “commercial” set-up with an editor snooping on me at all times; I knew I had to have one hundred percent artistic control of my project. With these things in mind, I contacted a colleague, Lars Fiske, in 2005. The previous year, we had collaborated on Olaf G. (No Comprendo Press, 2004), a biography in comic strip format based on the life of the Norwegian-German cartoonist Olaf Gulbransson. We wrote and drew our own parts of the sequence, and really “suited each other” visually. Besides, we get on extremely well.

We agreed that we would start a series of comic strip albums called CANON, an annual magazine just for us, where we could develop independent projects in the long term. Fiske got on with his graphic biography of the Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, and I with mine of Edvard Munch.

Left frame:[Man on the left, Steffen Kverneland]: Those arty, romantic, present tense, inside-the-head-of-Munch biographies, they’re all crap. Invented a hundred years post-Munch by nerds who fancy they’re cool.[Man on the right, Lars Fiske]: Myth-making dramatization, that’s all. And covert source plagiarism.Right frame:[Man on the left, Steffen Kverneland]: If I’m gonna make a Munch comic it’s gonna be a collage of proper quotes! [2nd bubble]: Gimme the flask![Man on the right, Lars Fiske]: Sheer geniush! Let the sources do the talking!

Also, at that time in Berlin, Munch was surrounded by an irresistible crowd of personalities: August Strindberg, Hans Jæger, Oda and Christian Krohg, Dagny Juel, the Satanist writer Stanislaw Prszybyszewski, and many other literary and intellectual go-getters.

Inspired by Hans Jæger, Munch worked intensively with autobiographical material and dramatized his own life in writing and images. He even compiled an illustrated diary that is pure gold as the basis for a graphic narrative. I indiscriminately quote his words and borrow from his pictures.

The history of Munch the artist is also the history of Munch the man, because his images are so autobiographical. He might have had a powerful experience as a young man, returned to it in writing ten years later, captured it in an iconic painting ten years after that, only to revisit the memory at irregular intervals well into his old age.

The medium of the comic book opens up new approaches to biographies of artists. In the drawings, I could for instance begin by showing how Munch responded to a particular theme and then reconstruct how, many years later, he set about painting the pictures we know. This entailed switching between different times, so I introduced colour schemes to keep them separate. “The present” was Berlin between1892 and 1895 and drawn in full colour on bright paper. The past, in flashbacks, was drawn on ordinary unbleached paper (a brownish base that’s very satisfying to draw on) and the narrator, Munch as an old man, is drawn in realistic shades of grey.

I also try to enrich the graphics as much as I can by creating a “Munch-like” visual world and by drawing scenes inspired by Munch’s own motifs. Munch’s soft line makes a terrific contrast to my own angular style, so just in terms of drawing I have a lot to play with. I also take a positively autistic pleasure in drawing hyper-precise copies of his paintings.

I haven’t found out anything that Munch art experts and academics haven’t already documented and can’t offer any, more or less speculative, new revelations about Munch’s sex life and possible unknown offspring (e.g. an American nun), but have my own interpretation and subjective version of what kind of man Munch was.

There is a myth about the romantic artist Edvard Munch that has become stuck in people’s minds as the only truth about Munch. He is yet another a great artist being forcibly fitted into an ever-popular narrative of suffering; the anguished, starving alcoholic genius who, while half-mad and persecuted by his contemporaries, created Art of eternal worth. Historians and art historians have long ago nuanced and corrected this one-dimensional form of the myth about Munch. Regardless, it is still endlessly regurgitated by journalists and biographers.

It is true that Munch himself adored aspects of this myth. He had a self-pitying streak and more than once portrayed himself as crucified. But he moved in a literary circle of neo-romantics, symbolists and fin de siècle-fantasists who were devoted to grand, passionate feelings. In their art, they revelled in misery, decadence, mental turmoil and decline. One couldn’t be too down in the dumps. It was simply hip.

That Munch’s life was a black hole of misery was the story I, too, was fed with my mother’s milk. I felt both amazed and inspired when I began to read what he himself had written, particularly in his private correspondence. For one thing, I found that Munch could be funny and had a sharp sense of irony, towards himself as well, and plenty of optimism. Wow!

In other words, Munch, like most people, was a complex human being. His life had its ups as well as its downs. Once I had realised this, the hero in my comic suddenly became much more interesting and, of course, more plausible.

Munch was also aware of the marketplace and how to sell his art. That he rose and advanced was above all due to his unshakeable belief in his talent and his iron will, coupled with the ability to market himself and determination to fight every inch of the way. Very ambitious from early on, he was one of the first and the youngest artists in Norway to have a solo exhibition. He organized it himself, rented the venue, arranged the advertising and so on. From the start, he was supported by the radical artistic set as well as by his family.

He became seen as one of the leading painters of his generation and, quite early on in his career, the Norwegian state awarded him an artist’s grant-in-aid for three successive years. At all times, Munch was surrounded by friends, supporters and generous paymasters. That his art was actively reviled in some circles was entirely according to plan. Munch deliberately worked on standing out from the mainstream and loved provoking people who had a conservative taste in art.

I don’t want to diminish the many grim events in Munch’s life, but these are not essentially different from the experiences of “ordinary people” of his time. For instance, there was much illness and death in his close family but not more than in most families. Christian Krohg had to deal with very similar circumstances without anyone paying a great deal of attention to him.

My narrative about Munch is not a categorical rejection of the Munch-myth, but an irreverent attempt to correct common assumptions about him and add nuance to his image. I let a little light and air and humour liven up the sad, slightly dull atmosphere around him.

Now, after having spent seven years with Munch, I am convinced I’ll have withdrawal symptoms. And I will miss his chin.

Wallpainting (4m x 7m), Litteraturhuset (Norwegian House of Literature), 2007

To the Eurozine Gallery

To the Eurozine Gallery

Published 4 April 2014

Original in Norwegian

Translated by

Anna Paterson

First published by Aftenposten, 24 October 2013 (Norwegian version); Eurozine (English version)

© Steffen Kverneland / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Queer histories in Estonia(n): featuring 19th-century writing defying heteronormative expectations; why ‘cis-gender’ is a useless concept; Russian-speaking LGBT+ activism; and a history of trans rights in Spain.

Two years have passed since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Those defending against continued aggression, displaced from their homes and previous lives, deal with daily, compounded loss. Artists, reflecting on the trauma, tackle the questions that aim to make sense of life when everything is affected by death.