If we look back to 1989, it is clear that those newspapers that survived the transition from communism have certainly made progress in re-defining their role in today’s society. The Romania libera of today is completely different from the militant anti-communist newspaper of the 1990s: information has been separated from opinion, graphics have improved and the paper has added a team of quality columnists. Not even the truth is what it once was but now changes shape as it passes through a process of reconstruction and changes in public opinion. For some years now, Cotidianul has been repositioning itself as the paper “for the discerning reader”, and has introduced us to the marketing technique of free inserts – books, CDs etc – later adopted by other papers. Evenimentul zilei has risen above its “chicken with three legs” reputation and has fought to transform itself into a newspaper of reference with the creation of a “senate” or advisory panel of distinguished columnists.

But none of this has so far translated into better circulation figures. Cotidianul has had difficulty raising its readership – despite its inserts – and the circulation of others has fallen compared to a few years ago when they were not part of the quality end of the market. It is true that the change in profile covers a period when newspaper readership is falling across the board, partly because of the development of the Internet, but also because our new middle class is still preoccupied with redefining its tastes, cultural behaviour and ideological options. In such a context, where things are still seeking their level, a lack of patience is a serious mistake. At Romania libera, Evenimentul zilei and Cotidianul, there have been personnel changes in the management and editorial teams, some prompted by the “lack of results”; at Gandul, a new paper targeted at the same market as the quality dailies, founder and director Cristian Tudor Popescu resigned because of differences with the management team.

It would seem that as they become more professional and identify their own profile more clearly, our newspapers are discovering what has been evident in other countries for a long time: the conflicting interests of journalists and managers, of editorial content and market demands. With an eye on circulation and the belief in their ability to promote and sell a “product”, managers make a quick survey of the market, form strategies and demand instant results. They then put pressure on the journalists to adapt to public demand, dismissing the latter’s notion of “writing well” or “offering the reader interesting topics treated professionally” as outdated, romantic ideals that have nothing to do with creating a successful newspaper. For managers and marketing specialists, what matters is promotion, campaigns, sales. They may be justified in thinking this way, particularly when their arguments are backed up; yet “strategies”, sales techniques and promotional campaigns are not enough on their own. You cannot sell potatoes and caviar in the same way.

Quality newspapers – especially when addressing a public that is fickle and still caught up in adjusting to the new realities in this part of the world – are hard to sell but are needed more than ever at this juncture. Le Monde, The Times, La Stampa or the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung all have a long history behind them but are all currently experiencing the same kind of financial difficulties. Our newspapers in their present form are only a few years old. But it is not enough for managers simply to have patience and make their papers more efficient: if they are to increase circulation and revenue, they must find creative solutions. And this is where the creativity and talent of journalists and commentators is crucial. In spite of the results of their market research, management and marketing teams must, at times, just trust the intuition of their best journalists, as the history of the press demonstrates time after time.

Prestige and practical benefits

However, if the dailies seem to be more or less on the right path, there is one sector of the quality press that is virtually non-existent in Romania: quality magazines. We do not have a news magazine such as Time, L’Express, Focus, Panorama or Newsweek. While Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic do have such magazines, in the Romanian market, this important sector of the written press is completely absent. The few attempts to create quality magazines of this kind failed completely; whether the failures were due to management mistakes, editorial teams or to a public that was “not ready” for them is irrelevant. While it may be true that such magazines, with their rich and varied content targeted at the middle classes, need huge circulations and adequate funding to survive, in other countries, though not here in Romania, there are examples of similar magazines that exist on very modest means. They do not have a colossal circulation, but function efficiently and make a profit – or at least break even. Die Zeit is a weekly with news, debates, politico-social and cultural ideas, targeted at an elite, intellectual readership. The New Yorker is the weekly “of those who matter”, among the so-called trend setters in cultural tastes, ideas and attitudes. Prospect is a UK monthly specializing in political and social themes, but firmly rooted in an “intellectual” or “cultural” perspective. All of these – and many others could be cited – survive in highly competitive markets because their editors and journalists guarantee the publication’s quality and prestige, and their managements know how to sell the product, basing their pitch precisely round the unique personality of these magazines, rather than falling back on standard marketing procedures.

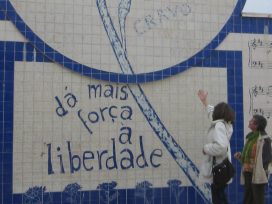

Some of these magazines are part of large press trusts – the New Yorker, for instance, is published by Condé-Nast – others are independent. But the important thing here is that “prestige” has a market in which public, journalists and managers all believe. Maybe the best example of this is the Portuguese Jornal do Letras. A magazine of great intellectual prestige, whose regular contributors include Nobel Prize-winning author José Saramango, Jornal do Letras was taken over in 1992 by the Swiss media and communications group Edipresse, who are also present in Romania and specialize in entertainment, hobby-related and women’s magazines. It was Edipresse’s first acquisition in Portugal and was made regardless of the fact that the journal had a circulation of only a few thousand and was of no commercial interest. Today, Edipresse owns around 50 titles in Portugal – celebrity magazines, women’s and teenage magazines, economic and news publications, TV guides and so on – but Jornal do Letras remains the jewel in its crown.

Cristina Simion, general manager of Edipresse Romania, comments in an interview on Iulian Comanescu’s blog that Jornal do Letras brings an “immense image boost” for the trust, but that it also has a practical value: “It was an excellent seed bed of very intelligent editors, who already have indisputable prestige … which Edipresse [or Edimpresa-Editora as it is known in Portugal since the creation of a joint venture with the Portuguese Impresa – ed.] has used to launch other publications.”

The quality press, even in such a sophisticated manifestation as Jornal do Letras, can reap concrete benefits for managers and marketing teams – but only for those with patience, who think long term and look beyond their own back yard. And we do have such people at home though I’m not sure how many recognize this: people like the members of the “senate” at Evenimentul zilei and some of the commentators from Cotidianul, Romania libera, Adevarul and other papers, including some local titles. All these were “crowned” with publications such as Contrapunct (from the beginning of the 1990s), 22, Romania literara and, if I may conclude the list thus, with Dilema Veche.

It is easy to complain about the quality of the press in Romania, we all do it all the time, journalists, managers, readers. In the logic of lamentations and of our inferiority complex, we can say not only that “we don’t have a Le Monde“, but also that our tabloids are worse than the German Bild or the UK Sun. But the quality of the press overall depends on its relationship to the quality press, which addresses itself to a public somewhat more sophisticated in taste, but with ideas and opinions that matter to society. In this sector, the winning party will be those managers who have the patience over at least two or three years to find a formula that is sufficiently intelligent to deliver quality newspapers and journals to a waiting public. Something that demands not arid disputes but creative harmony between journalists and managers.